The Forgotten Jewish Great War Poet, Revived

Long-gone writer is introduced to new readers with the help of graphic art

In 1915, a young British Jew named Isaac Rosenberg self-published a book of poetry called “Youth.” He also joined the army. Three years later, when he was 27, he was killed on the front lines in rural France. Some critics think he was one of the greatest English poets of the 20th century. So why haven’t you heard of him?

Most Americans know little about the so-called Trench Poets, British soldiers who wrote poetry during combat in World War I. The 2014 anthology Above the Dreamless Dead aims to change that, pairing works of many of the poets (the best known of whom is probably Wilfred Owen, along with Siegfried Sassoon, another Jew) with sequential art by leading American and European graphic artists.

Rosenberg was born in Bristol in 1890 to poor Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. His father was a peddler; his mother took in needlework. When he was seven, the family moved to the East End of London. At 14, he had to leave school to work. He was able to return to study art at the University of London, thanks to tzedakah from charitable Jewish ladies in London, but financial success as an artist or poet eluded him. According to poetry collector R. Eden Martin, who profiled Rosenberg for The Caxtonian, a publication of Chicago’s bibliophilic society, Rosenberg tried sending his poetry to Ezra Pound, who initially dismissed him, but ultimately told Harriet Monroe, the editor of Poetry Magazine, “I think you may as well give this poor devil a show. Yeats called him to my attention last winter, but I have waited. I think you might do half a page review of his book, and that he is worth a page for verse.” Pound added: “He has something in him, horribly rough but then ‘Stepney’ East…. We ought to have a real burglar…ma che!!!” (Stepney was a ghetto-ish Jewish neighborhood. Oh, Ezra.)

Destitute, Rosenberg joined the army in 1915. He arranged for half of his pay to be sent home to his mum. Martin writes that Rosenberg showed up for military service “with a copy of Donne’s poems in his pocket.” He died in the trenches, his remains unidentifiable. Today, his name is engraved along with those of 15 other Great War poets in Westminster Abbey.

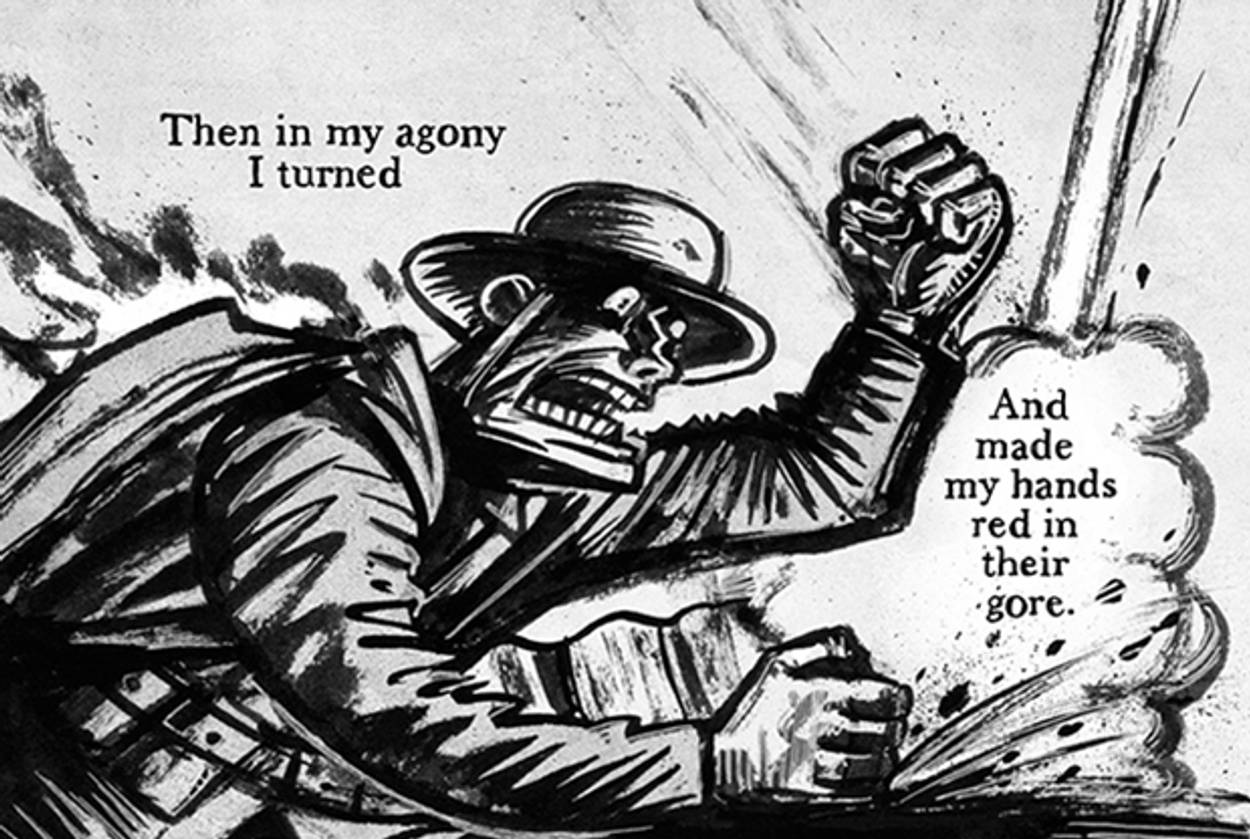

The Poetry Foundation says that Rosenberg “found a truly distinctive voice, one particularly indebted to the Old Testament and his sidelined Jewish identity.” Three of his poems appear in Above the Dreamless Dead. Two, “Break of Day in the Trenches” (which Paul Fussell called “the greatest poem of the war”) and “Dead Man’s Dump” (which author Geoff Akers called “the greatest and most profound war poem ever written”) are familiar to those acquainted with the Trench Poets. Artist Peter Kuper (who may be best-known for Spy Vs. Spy, which he’s drawn for every issue of Mad Magazine since 1997, but he’s also written graphic adaptations of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, and taught comics and illustration at Parsons, School of Visual Arts, and Harvard University) illustrated a lesser-known work, “The Immortals.” The poem’s despairing tone—ending in a seemingly offhand, grim, anti-climactic semi-shrug—is wedded perfectly with Kuper’s bold, bleak art.

Peter Kuper from Above the Dreamless Dead, reprinted with permission of First Second.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.