The Last Jew of St. Poelten

Hans Morgenstern’s family fled the Nazis before returning to Austria after the war. Now, as the only Jew left in his small town outside Vienna, he laughs darkly watching the rise of Europe’s new far-right.

Eighty-one year old Hans Morgenstern is the last Jew living in St. Poelten, a Baroque Austrian town 41 miles west of Vienna.

Morgenstern is a dapper dresser. His lightly flowing white hair is combed elegantly back. The bright white frames of his sunglasses peep out of the pocket of his neatly ironed T-shirt. When Morgenstern, a retired dermatologist, walks around St. Poelten, he is greeted by former patients. He likes to stop for coffee in the city’s cafes. Morgenstern enjoys his life here, but it is riddled with contradictions.

The latest of these contradictions is perhaps that the right-wing Austrian Freedom Party, in their campaign against immigration, is currently keen to woo Jewish voters. Casting anti-Semitism as an imported phenomenon that has risen with the recent arrival of large numbers of Muslim immigrants, they are trying to recruit people like Morgenstern to their cause.

It was September 2018 when I came to St. Poelten to speak with Morgenstern. We met in the town’s former synagogue. The temple has not been an active place of worship for decades but Morgenstern was a driving force in its preservation and helped pave the way so that it could be transformed in 1988 into a museum and the home to the Institute for Jewish History in Austria. With populist parties on the rise, Europe appears to be on the precipice of historical change. Here, in this institute for history dedicated to preserving the memory of the past built in the shadow of a lost Jewish community, speaking with the last Jew in St. Poelten, there is a unique chance to see the possibility and peril of the present.

Only 80 years ago, as Morgenstern points out, Jews were banned from the town’s coffee shops and could not even sit on a park bench. St. Poelten is the place from which his family fled in fear and from which his grandparents were dispatched to their deaths.

St. Poelten was home to over 1,000 Jews when Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. In all, 575 of the city’s Jews were murdered.

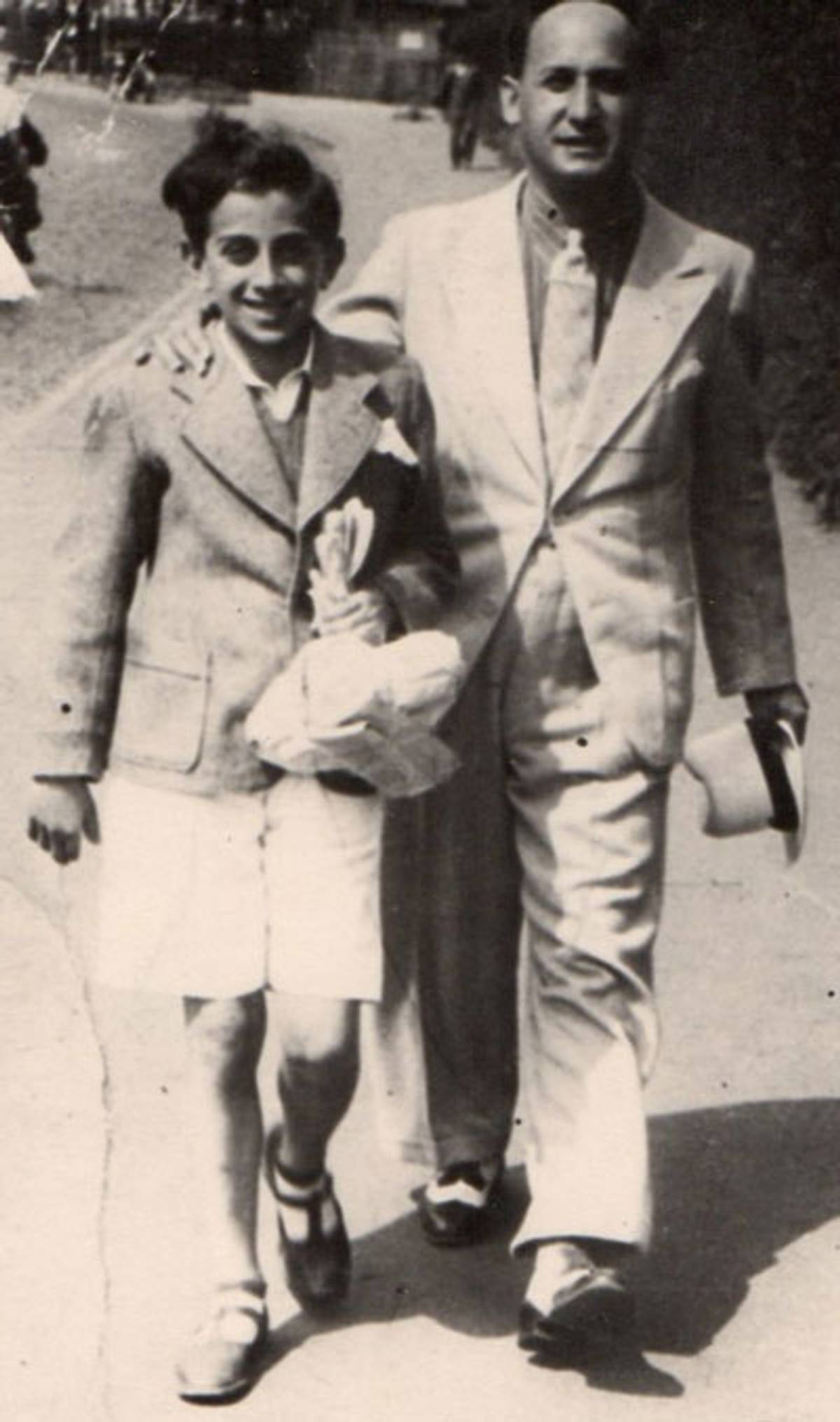

When Adolf Hitler led a triumphal parade through St. Poelten days after the Anschluss, Morgenstern’s father, Egon, a prominent local lawyer, watched from his office window. Nazi flags adorned the buildings, and cheering crowds lined the streets.

Within days, Morgenstern’s father had been banned from working, and the family was kicked out of its home. They wasted no time plotting an escape and managed to acquire visas to emigrate to Palestine. Morgenstern’s great-grandmother gave them her jewelry so the young family had the required collateral for the visa. The Morgensterns left for Palestine in 1939.

The family settled in Bat Yam, south of Tel Aviv, which was then, he says, “just a village in the sand.” Morgenstern adapted quickly, starting school and learning Hebrew. He loved the “beautiful beach.” He laughs at the joke he is about to make and tells me, “My father was a Zionist when he was a student but when he arrived in Palestine he wasn’t one anymore.”

Laughter punctuates Morgenstern’s sentences. “Life was hard. My father couldn’t work as a lawyer as his qualifications weren’t recognized and he couldn’t speak Hebrew. But more than that my father could not cope with the climate. He had been paralyzed by polio as a baby and was severely disabled. He could only walk with crutches that sank in the sandy streets.”

The Morgensterns were short of money and his parents, fearful of the looming war in Palestine, decided to return to Austria in 1947. Only a handful of the survivors did the same.

“There was a shortage of lawyers as those who had continued to work were all members of the Nazi Party and not allowed to practice after the war,” Morgenstern explained. He was 9 when the family settled back in St. Poelten “There was no Jewish community here anymore and we were, so to speak, alone until one year later my cousin Hans Cohen and his family returned.” A handful of other families came back but soon left. His cousin died in January. Morgenstern has no children. “It’s the end of the line,” he chuckles.

Morgenstern was 11 years old when he discovered that his grandparents had been murdered. “It was not pleasant for me as a child because I did not know who had been a Nazi Party member,” he says and laughs again.

Morgenstern has dedicated much of his life to recording the names and stories of the families who once lived in St. Poelten. “There was always a feeling of sadness in me, also a certain loneliness, that there is no Jewish community here anymore. It was important to me that these people will not be forgotten,” says Morgenstern solemnly.

We are chatting in the office of Martha Keil, the director of the Institute for Jewish History in Austria. When we met she was about to begin laying the first stones of remembrance in St Poelten. Twenty-eight stones will be laid in eight locations. The stone to commemorate Morgenstern’s grandmother Johanna Morgenstern was in a box on the floor of her assistant’s office. It was too heavy to pick up. Morgenstern’s grandmother Johanna had remained in St. Poelten and was forcibly moved to Vienna before being deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto and then murdered at Treblinka in September 1942.

Remembering the victims of the Shoah is an important part of Keil’s work. She says that “the most effective way this is done is in the memory book on our website that can reach the whole world but by placing these stones in a public place local people will encounter them while out shopping or going to the cinema. It will open their eyes when they are not expecting it.” Keeping the facts of the past clearly visible is a key way both Morgenstern and Keil want to fight the historical revisionism put forward by the far right.

Morgenstern listens carefully to her with his fingertips pressed together in front of his face. He says, with a wry tone, “For us Jews it is important, but the older generation did not like to commemorate because they had a guilty conscience.” Keil adds: “The good ones!” They laugh at the observation.

Yet, Morgenstern is quick to see the point from his neighbors’ side and adds, like a doctor giving a patient advice, “there was until recently a level of ignorance. People have no idea what happened. The people don’t know the facts. Only recently have they started to teach this in school.”

Growing up, Morgenstern says he did not sense any anti-Semitism but then tells me that his father had to call the school twice over anti-Semitic issues. There are two sides to his story and he slips from one to the other, from laughter to a serious grim demeanor. On the one hand, he grew up surrounded by people who had been members of the Nazi Party and, as he says, some of his friend’s parents were Nazis. “They are not Nazis,” he adds and then jokes, “Of course there were no Nazis in Austria after the war so even their parents were not Nazis anymore.”

Morgenstern stayed in St. Poelten because he had to help care for his sick father and then his elderly mother. “I never thought of going back to Israel. I am too lazy. Life was lighter here.” He laughs at the absurdity of his situation.

Morgenstern’s double life is reflected in local politics. “This is a socialist city and always has been,” he says. “The Social Democrats helped us and gave us the apartment where I live now but we are surrounded by a sea of right-wing voters.” St. Poelten “is a very safe place,” he says slowly. His voice speeds up as he says, “There is no anti-Semitism in St. Poelten. They are all very friendly with me because I am also very friendly with them!” Chuckling, he adds, “Even if they are friendly they can be anti-Semitic. They think the Jews are a bad people but I am the exception. The others are the bad ones.”

Pressing his fingertips together again he then says slowly, “Last week on the wall by my flat a swastika and the word Jew, ‘Jude,’ appeared. This is the first time this happened. It makes me fearful.” He doesn’t linger on this dark point. “Here’s another funny story!” he says. “When I called the Jewish community of Vienna to register the incident, the person who answered the phone did not speak German. I had to speak in English and the young man did not understand the word ‘swastika.’ How funny is that!”

The conversation turns back to the stones of remembrance, and he tells me his family from England are coming for the ceremony. “My cousin survived. His name was Otto Pelczer. He died, but he has a son Jeremy who is coming.” I mention that when I was a child our neighbors were called Pelczer. The father was called Otto and the son Jeremy. “You know him?” says Morgenstern, his pale, faded-blue eyes wide open. The conversation that flows so easily from him stops as he processes the information. Martha Keil adds that Pelczer is a very unusual name.

I have spent almost three years driving around Europe recording how the Holocaust is remembered and talking to survivors for a book project. I have drunk endless cups of tea with survivors and tried to understand their stories. Austria was the last place I expected to find myself part of the story. Flummoxed, I am confused about what to ask next. Keil gives me the email of Jeremy Pelczer and suggests a tour of the synagogue.

The conversation with Morgenstern and Keil turns inevitably to contemporary politics and the rise of right-wing parties across Europe. “It’s a mental burden for me to know that there are young people who think that way,” says Morgenstern “but I cannot do anything about it.” He points to deeply embedded anti-Semitism on the Austrian right and the importance to contemporary politics of remembering the horrors of the past.

I bid farewell and do not mention that there is another dark thread that brought me to St. Poelten. In July 1995, I was driving back to London from the former Yugoslavia, where my husband had reported on the war there for four years. The foreign editor had decided that not much was going on anymore in the region. We stopped in St. Poelten. It seemed a cheaper option with a young family than Vienna. That night the murder of over 8,000 Bosnian Muslims began in Srebrenica. For this reason, I had never forgotten St. Poelten. When I was looking for a story to write about Austrian Jews I began to look in St. Poelten, as it was one of the few cities I knew the name of.

Back in Vienna, I email Jeremy Pelczer. He is indeed the gangly teenager who knocked me out with a cricket ball while we were mucking about on the lawns of the modern housing estate where we grew up in the leafy London suburb of Richmond, except Jeremy is now a successful businessman and grandfather from Somerset.

As I click about on the institute’s memory book, I quickly see why Keil has told me that it is their most important work. Otto Pelczer, I discover, did indeed live in Vienna as my mother had told me. The family moved from St. Poelten to an apartment on Urban-Loritz Platz. When I go to look for the building it appears to have disappeared. This is the surreal world of tracing the Holocaust. Otto Pelczer’s mother, Grete, was Hans Morgenstern’s aunt. She had been born in Prague and, after the Anschluss, the Pelczer family fled to the Czech capital.

It was from there that Otto Pelczer left for England, as one of the Czech children saved by Sir Nicholas Winton, a young British humanitarian who arranged the rescue of 669 children from Czechoslovakia. Jeremy tells me he left by train. German soldiers stood along the platform. His mother, Grete, and his father, Ludwig, were deported to Theresienstadt. They wrote him a final letter from the ghetto before they were murdered in Majdanek in Poland in September 1942.

I understand now why Otto Pelczer was often in my mother’s words “resting” and should not be disturbed. The walls in our modern townhouses were paper-thin so when Mr. Pelczer was “resting,” I was sent out to play and told not to make too much noise. Jeremy was usually outside practicing with a cricket ball.

At Majdanek, there is a huge mound of ashes and bones protected under a concrete roof. On the eve of Yom Kippur Jeremy calls me. He tells me he knows that it is Yom Kippur as “Hans keeps me up on things, but we followed Mum and are members of the Church of England.” I tell him my husband is Jewish and I am rushing to get to synagogue. We have slipped across the parallel lines. On the institute website, I notice one of their projects is called Displaced Neighbours.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Rosie Whitehouse is the author of The People on the Beach: Journeys to Freedom After the Holocaust.