The Man Who Made ‘MAD’

An award-winning biography about Harvey Kurtzman tells the story of how a Jewish comedy icon revolutionized American satire

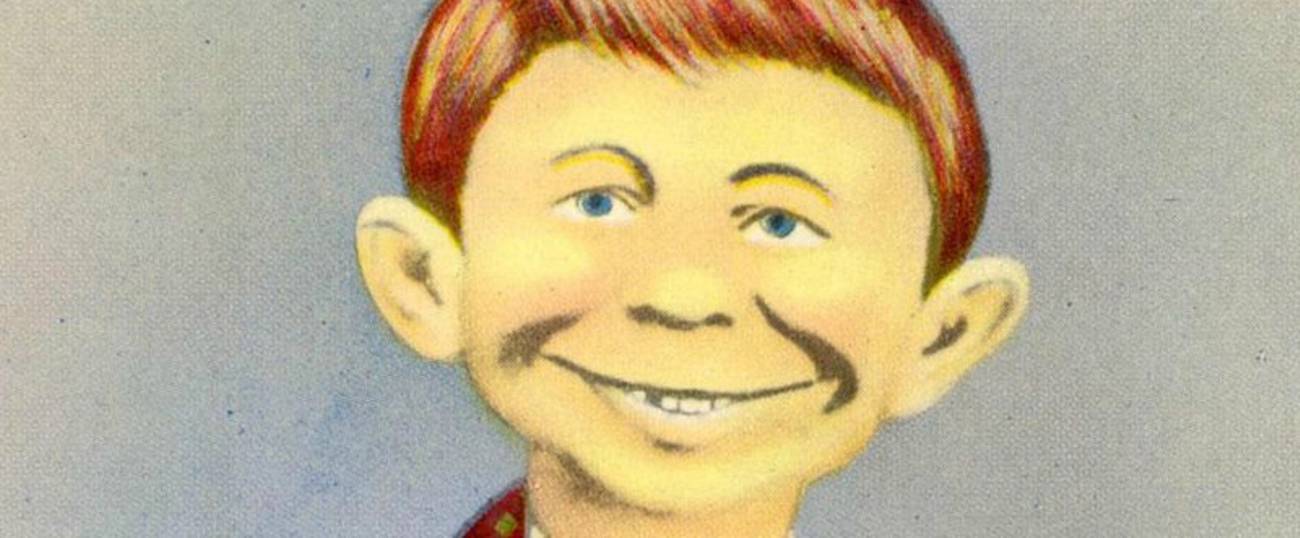

Last week, at the 2016 Will Eisner Awards, the comics industry’s highest honors, the winner for Best Comics-Related Book was Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created MAD and Revolutionized Humor in America. The book, written by Bill Schelly and published by Fantagraphics Books, explores the life of the guy about whom The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik said, “Almost all American satire today follows a formula that Harvery Kurtzman thought up.”

After Kurtzman’s death in 1993, his friend Art Spiegelman was furious at The New York Times because the paper’s obituary had said that Kurtzman had “helped” create MAD magazine. Spiegelman noted, “I called to tell them it was like saying Michelangelo helped paint the Sistine Chapel just because some Pope owned the ceiling.” The paper issued a correction the next day.

Kurtzman, a Brooklyn boy, was born in 1924. His parents were both from Ukraine. His father died of a bleeding ulcer when he was only 4; Harvey and his older brother Zachary spent a few traumatic months in an orphanage while his mother got her life together. She soon remarried another Russian-Jewish immigrant—a brass engraver in the printing business—and Harvey came to see him as his real father. “I loved growing up in Brooklyn,” he said. “It was like a big playground, filled with surprises.”

A short, unathletic, unassuming-looking guy (he was described as looking “like a beagle who is too polite to mention that someone is standing on his tail”), Kurtzman showed artistic talent at an early age and attended the High School of Music and Art, where he met his future MAD collaborators Will Elder and Al Jaffee. In 1942, his stepfather was sent to jail for conspiracy and counterfeiting (he was making fake war ration coupons). The following year, Kurtzman went into the military and was put to work drawing war comics. He liked the work, but hated the images in other artists’ work of “the American soldier killing little buck-toothed yellow men. I thought that was terrible,” he said. Author Schelly posits that as a Jew, Kurtzman knew what it was like to be the Other.

After the army, Kurtzman used an educational comic he’d drawn on the dangers of syphilis to get a job at EC Comics, where he worked on books called Frontline Combat and Two-Fisted Tales. They didn’t exactly glamorize war. During the Korean conflict, the government investigated EC for sedition under the Smith Act, because Kurtzman and his colleagues were creating work “detrimental to the morale of combat soldiers” that could “undermine troop morale.” J. Edgar Hoover himself sent a letter to a special agent in NYC asking him to look into Kurtzman. But the FBI investigation found that no one at EC was associating with Communists (lucky for Kurtzman his parents had a different last name, since they’d possibly attended Communist meetings) and no one had any connection to criminals (likewise, whew). The FBI decided that Kurtzman’s work was “unnecessarily graphic,” but not deserving of prosecution. (In 1967, Kurtzman got in hot water with the FBI again, this time for a parody of J. Edgar Hoover in Playboy.)

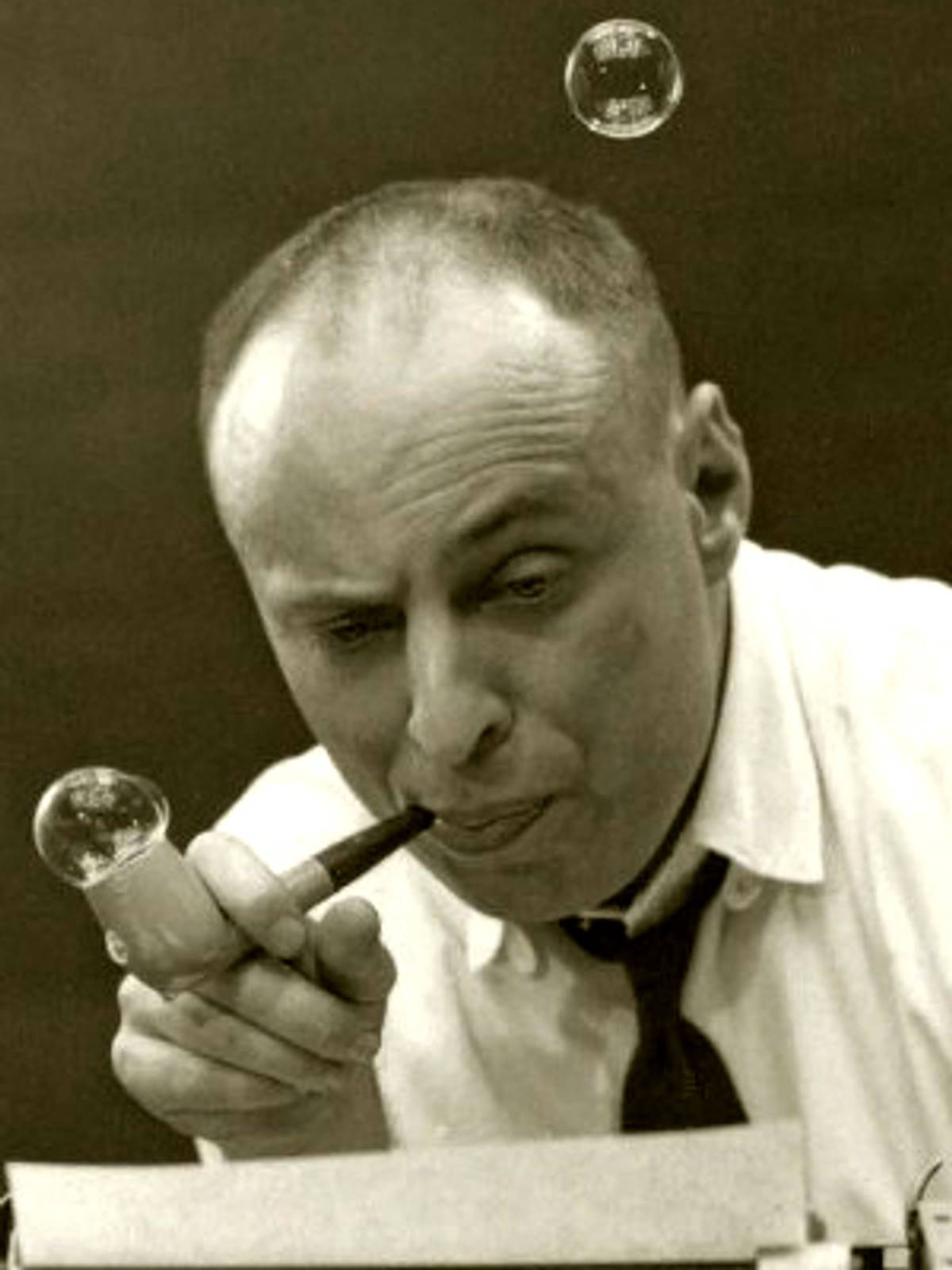

In 1954, Kurtzman started a satirical comic. He (or his publisher Bill Gaines—both claimed credit for the idea, as well as for the name MAD) felt he was spending too much time on research for the two war comics, and he could write humor a lot more quickly and make more money. The first issue had a comic called “Ganefs!” (about thieves, of course) and MAD quickly found its groove doing pop culture parodies (Mickey Rodent! Shermlock Shomes! Bat Boy and Rubin! Little Orphan Melvin! From Eternity Back to Here!) and using semi-Yiddish works like “farshlugginer.” Issue #4’s Superduperman was an early example of his style. Pondering his nemesis “Captain Marbles,” who turns from a nebbish-y boy to a red-clad muscleman after saying “Shazoom,” Superduperman wonders, “Vas ist das Shazoom?” (Apparently shazoom is an anagram for “Strength, Health, Aptitude, Zeal, Ox, power of, Ox, power of another, and Money.” Hey, two oxen!)

Copyright law was in its infancy, and after Superman’s publisher sent a cease-and-desist letter, Gaines wanted to apologize and stop doing parodies. Kurtzman refused. (Gaines later called him a hero.) Eventually case law established that satire is protected and is only a copyright violation if it could be mistaken for the real thing, which MAD magazine obviously couldn’t be. The magazine quickly became known for its snarky takes on comics and movies. Even in his early work, Kurtzman enjoyed breaking the fourth wall in a post-modern way. (In 1947, one of his characters points to us, the reader, and says “See that character there? Looks like a human being, only, it’s just printed ink on comic book paper.”) MAD continued this tradition, which was then adopted by artists as diverse as the creators of Airplane, SNL, and Maus cartoonist Spiegelman.

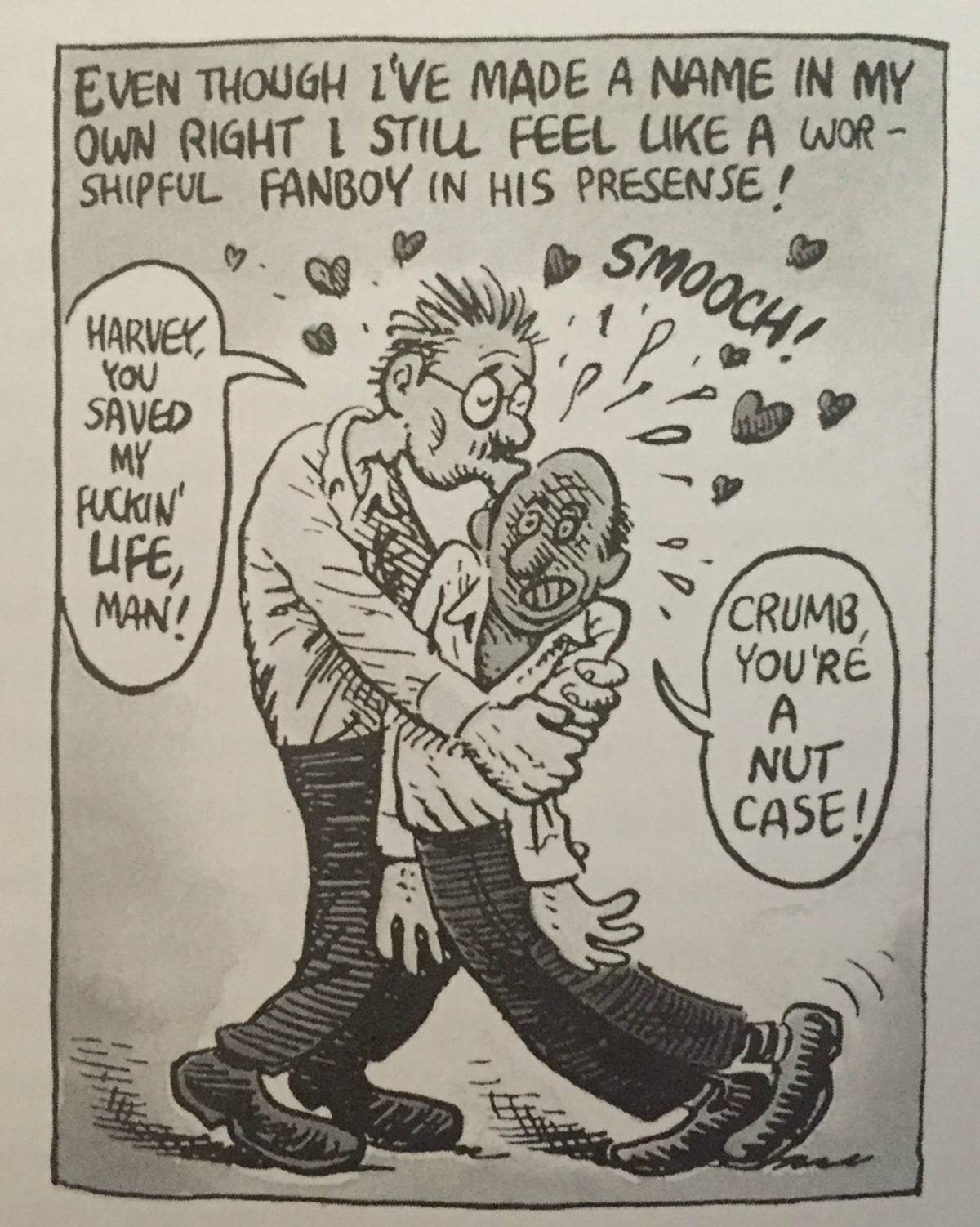

Kurtzman grew MAD from a skinny comic to an actual magazine, and ushered in a line of MAD paperback books. But Gaines and Kurtzman grew apart. In 1956, Kurtzman was lured away by Hugh Hefner to start a magazine called Trump! It was going to be full-color, sophisticated, bimonthly, offering not only comics but satirical pieces illustrated by top artists. But Hefner pulled the plug after only two issues. (Later this month, Dark Horse Books will publish Trump!: The Complete Collection, reprinting both issues and part of the never-published third issue.) Kurtzman then started Help! and Humbug! which also tanked. But he had an eye for discovering top talent: He was an early proponent of R. Crumb’s work; he was plugged in to comics scene in Europe (which always took sequential art more seriously than America did); Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam was his assistant at Help! and Gloria Steinem was Help!’s gal Friday. “Everybody loved Gloria,” Kurtzman reflected. She had a great phone voice and “I was convinced…she could get anybody to do anything.” (Happily married himself, he later tried to set Steinem up with Hugh Hefner. It didn’t work, because unbeknownst to Kurtzman, Steinem was at work on her expose of the Playboy Club, going undercover as a bunny. She avoided being in a room with Hefner for fear he’d recognize her.)

Help! was extremely low-budget, so Kurtzman had to figure out how to create humor from less. He came up with “fumetti,” Italian for little puffs of smoke, which refer to word and thought balloons in comics. In America, “fumetti” came to mean stories acted out in photographs accompanied by word balloons. (In Italy they’re called fotoromanzi.) One fumetti used the actor John Cleese as a dad who’s fallen in love with his daughter’s Barbie. (The image of Barbie’s tiny lace panties flying through the air is unnerving.) Another, published just as Alfred Eichmann went on trial in Israel, showed the Nazi pouting, “Ever get the feeling that the whole world’s against you?” That triggered a huge fight between Kurtzman and his publisher. The publisher said it was offensive; Kurtzman said everything was fair game for satire if it was handled in good taste, which this was. It destroyed their relationship.

After leaving MAD, Kurtzman’s only longtime drawing gig turned out to be for Hefner; he did a strip called “Little Annie Fanny” for Playboy for 26 years. Basically, it was an excuse to get the wide-eyed, adventurous title character naked. He loved doing the research for it—on Playboy’s dime, he went to a mud-wrestling tournament in Green Bay, Wisconsin, to a wild west bar with a mechanical bull, and to California redwood forests and swingers’ clubs. And he needed the paycheck. But he hated the strip’s artistic limitations. He told an interviewer in 1980, “Yes, I get tired of it. But I get tired of a lot of things: paying the bills, taking out the garbage, shaving.” He supplemented his income with work for Esquire, TIME, Look and The New York Times Magazine. He did three award-winning animated mini-films for Sesame Street and became a beloved teacher at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. In 1988, the comics industry named one of its most prestigious awards, The Harvey, after him. Sadly, toward the end of his life he developed Parkinson’s disease, which affected his memory and artwork, before he died of cancer in ’93. A secular Jew, he was cremated. His ashes were, Schelly poetically notes, “scattered in his backyard in Mount Vernon amid the blooming rhododendrons and forsythia.”

Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad And Revolutionized Humor in America is a book the size of a small cat. There’s a lot of inside baseball that will have those of us who are not familiar with the vast world of comics artists flipping pages quickly. I don’t think it justifies the “revolutionized humor in America” subtitle, which would require giving us examples and quotations specifically showing us who was influenced by Kurtzman and how. It doesn’t have enough examples of Kurtzman’s work. (Maybe I’ll find that in The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics, by Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle, which was featured in a Vox Tablet podcast a few years ago.) But Schelly’s book is still a fascinating read, astonishingly relevant to us aging writers and artists trying to make a living in a changing media landscape. (What, me worry?)

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.