The New American Judaism

How COVID, suburban migration, and technology are sweeping away legacy institutions and shaping a new 21st-century form of American Jewish identity

Ever since God chased Adam and Eve from Paradise, the Jewish experience has been defined by constant movement. In the past 3,000 years Jews shifted from a small sect escaping exile in Egypt to a national Temple-based model, then to a Talmudic diaspora, hunkered down in European ghettos and shtetls. That was followed by waves of migration at the turn of the 20th century that inaugurated a new promised land in America and over 100 years of Jewish American advancement organized around what became a lavish institutional Judaism.

Today American Jews are in the midst of another epochal shift. In short, the classic 20th-century archetype of American Judaism as a culture concentrated in big metropolitan regions and organized around major institutions has come to an end. The saga that began with Ellis Island is giving way to a new Jewish identity in which the internet now plays the role that urban neighborhoods once did as a hub of communal organizing and religious teaching.

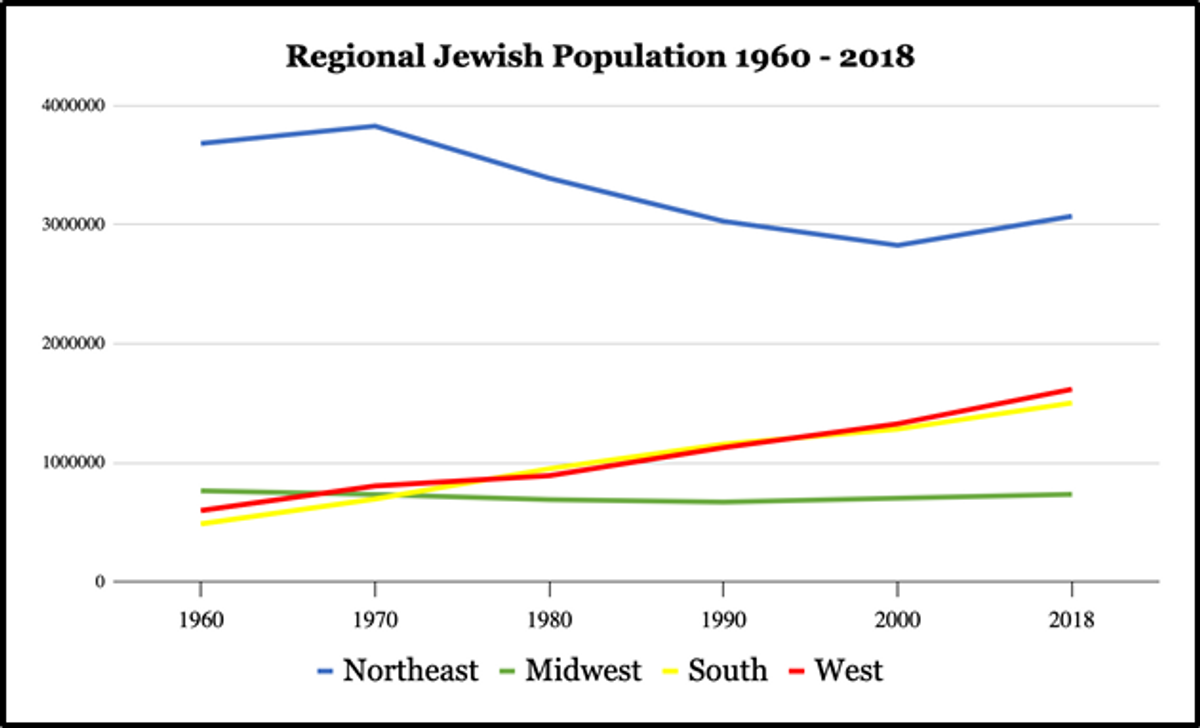

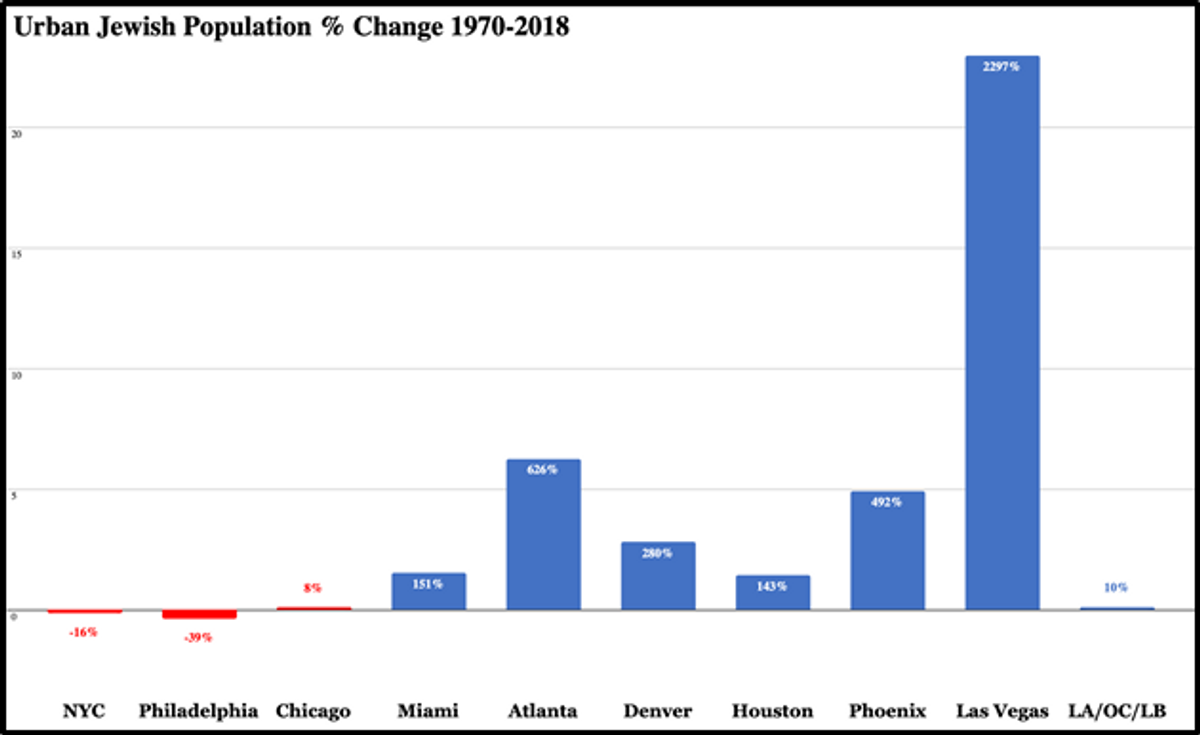

The changes reshaping Jewish identity in America have been accelerated by the current pandemic on three critical fronts. The first is dispersion from traditional centers, notably inner cities like New York, to faster growing regions in the South and West. This pattern has seen the fastest growth among Jews both on the urban periphery as well as primarily suburban, sprawling, car-dependent cities such as Miami, Los Angeles/Long Beach, Houston, Atlanta, and Denver.

Even before COVID, sociologist Stuart Schoenfeld discovered that while Jews may be “city dwellers” who are “disproportionately concentrated in metropolitan areas,” the majority do not actually live in the urban city core. Indeed, he finds, “urban Jews are a minority among Jews and a minority among other urbanites.” In Miami, only 7,000 (5%) of the city’s 123,200 Jews live in urban core areas while in Los Angeles, they are 13%, and 17% in the Bay Area. Judaism after COVID is likely to continue its movement away from dense city centers.

A second major change has been the growing use of telecommunication technology, a phenomenon again hastened by the pandemic, which has forced synagogue doors to close.

In a process reshaping other religions as well, the ritual and intellectual observances of Judaism are going online. Arie Katz, founder and chair of Orange County, California’s Community Scholar Program, built a structure to bring world class Jewish scholars, writers, artists, and musicians to Southern California so he could learn from the best by crowdsourcing the cost. Since Katz, the child of South African immigrants, moved his programs online in March in response to COVID, average program attendance has increased threefold, and he has been able to increase the number of unique offerings from two a month to four or more per week. Moreover, his member base, once restricted geographically to Southern California, now has global reach with participants in New York, Boston, Seattle Europe, Latin America, and Israel.

The third factor has been the emergence of ad hoc or “fluid” religiosity. This is a trend seen in other religions as well, where people, particularly millennials, increasingly seek to navigate their own paths to spiritual fulfillment outside denominational and synagogue loyalties. Broadly speaking, the Reform and Conservative movements—vital for first- and second-generation Jewish immigrants who wanted to honor their traditions while fully assimilating into American culture—are now on the decline. In some sense they are victims of their own success. By providing a version of Jewishness that accommodated the demands and pulls of America’s modern commercial culture, they became less essential to subsequent generations that were already successfully assimilated.

The flip side of this story is the growth of American Orthodoxy in the 21st century. While their secular counterparts are shrinking, the Hasidim and other more traditionally observant Jewish communities in America are experiencing a surge of growth. But it’s not just organizations like Chabad that are flourishing. There also is the rise of diverse unaffiliated and independent minyanim, and an explosion of what can be termed “special interest Judaism,” ranging in focus from environment and social justice to cooking and spiritualism. There’s even a successful Boulder, Colorado-based program called “Adventure Judaism” where the rabbi frees people from their synagogues and video screens to encounter their Judaism as they “climb mountains, go skiing, play the guitar, and sing around a campfire.”

Beneath these structural changes are deeper existential realities that American Jews will have to face. Younger Jews turning away from the traditions and institutions of their faith cannot be written off simply as spoiled millennials. Many are responding to the legitimate failures of the American Jewish establishment to address their communal and spiritual needs. The postwar configuration that served upwardly mobile baby boomers has not adapted to a new world in which young people are less economically secure, and face a harder time starting families and a disintegrating social consensus and loss of community.

Another challenge facing American Jews will be the loss of their position at the center of the Jewish story. Over the past 72 years Israel has reemerged as the world’s largest and most consequential Jewish community. America’s Jewish communities are still among the most secure and powerful in history of the diaspora, and will likely remain so well into the future. But the relative diminishment of America’s role as Israel consolidates its status as the undisputed capital of world Jewry, will continue as well and will require a new conception of the relationship between the two nations.

Our aim here is twofold: to describe the major forces shaping the future of American Judaism and to draw attention to the challenges that threaten the continued thriving of American Jewish religious practice, community building, and family life.

The Question of Survival

The optimism, bordering on arrogance, of Alan Dershowitz’s 1991 bestseller Chutzpah, was followed six years later by his much less widely celebrated The Vanishing American Jew, which suggested that the community here was “in danger of disappearing.” The primary culprit was not white nationalists or radical anti-Zionists, but increased acceptance, affluence, and intermarriage, which Pew found reaches as high as 58% of all Jews married since 2005 and 79% among self-identified “Jews of No Religion.” That is if they get married at all.

Kvetching about intermarriage rates hides Pew’s more startling finding, that “the share of Jews who are married appears to have declined since 2000 (down from 60% in the 2000-2001 National Jewish Population Survey to 51% today). ”The “newest threat to our survival as a people,” Dershowitz wrote, “is principally a product of “our success as individuals.”

Clearly, even before COVID, these demographic forces were pushing synagogue Judaism towards secular decline. Jack Wertheimer, professor of Jewish American history at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, suggests that all denominations are struggling, and their numbers declining. The only real growth is Chabad, whose number of synagogues has tripled since 2001 from 346 to approximately 1,036.

Critical to understanding this overall erosion in Jewish expression is the alienation felt by the millennial generation. Brandeis professor Matt Boxer explains that many millennials are turned off by the dominant narrative that Judaism is about “survival and continuity” and are further “repulsed by rhetoric about intermarriage or anti-Semitism posing existential threats to the survival of the Jewish people.” Depression-era Jews and their boomer children were both haunted and motivated by an overriding question: Will Judaism survive? But millennials ask, “why does it matter that we survive?” Their concern is for the future of humanity and their own spiritual journey.

The situation calls for a wholesale refocusing of Jewish life away from obsolete denominational patterns and the dual fixations on Zionism and anti-Semitism, and toward a renewed conception of Judaism as integral to daily life and struggles.

There’s a conflict, as Boxer notes, between millennial demographic patterns and the traditional life trajectory that synagogues are structured to serve. American synagogues don’t know what to do with young people between their b’nai mitzvah-age adolescence and the time they have children of their own. This “doesn’t work for millennials, who are staying in school longer and getting married and having children later in life (if at all).”

Millennials also face far worse economic prospects than their boomer parents, having suffered through the Great Recession, and now the pandemic quasi-depression—a situation that could be even worse for the generational cohort coming after them. Economic insecurity makes them reluctant or even unable to pay for expensive memberships and holiday costs at temples designed to cater to more affluent boomers. But as Rabbi Sid Schwarz, author of Jewish Megatrends, notes, it goes beyond a simple cost calculus. Schwarz founded the organization Kenissa to connect people “leading contemporary efforts to re-define Jewish life” to support “their efforts to create communities of meaning.” Schwarz argues that the high cost of living a Jewish lifestyle under the old synagogue model that included Jewish day school, camp, and Federation-giving, no longer resonates with many younger Jews—even those who were brought up within the system. The problem is systemic: Institutional Judaism fails as “a value proposition.”

And then there is a growing disconnect between generations as to what constitutes Jewish identity. Andrés Spokoiny, CEO of Jewish Funders Network, suggests “Jewish identity” has become a useless concept, no more than a placeholder. Many have dropped it altogether and moved to a focus on Jewish peoplehood and mission. “The last update to our software was 100 years ago” leaving Jews, Spokoiny argues, in desperate need for a “reboot.”

In other words, what is needed now is for more than just a patch. The situation calls for a wholesale refocusing of Jewish life away from obsolete denominational patterns and the dual fixations on Zionism and anti-Semitism, and toward a renewed conception of Judaism as integral to daily life and struggles. “Jews no longer necessarily discover Judaism through Jewish texts, rituals and traditions,” notes Rabbi Debra Orenstein. “Often Jews discover Judaism through their personal quests and journeys—finding, as a seemingly belated surprise, that Judaism has something to say about their lives and circumstances after all.”

None of this suggests American Judaism won’t survive, but in order to thrive it must change, and dramatically. The diaspora has always been built around Martin Buber’s notion of creating “a vocation of uniqueness.” How much this diaspora culture will endure depends almost entirely on what happens in North America. After all, the diaspora elsewhere—in Latin America, Africa, Asia, as well as Europe, now barely home to 10% of the world’s Jews, is in rapid, terminal decline. Today the North American Jewish population, along with Canada, constitutes over 70% of the total diaspora population.

In the last third of the last century, American Judaism was revitalized, and repeopled, by the movement of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Iran, Iraq, and South Africa. Yet America is no longer the primary destination: Since 1990 Israel has attracted between 70% and 80% of Jewish migrants from across the world. Following current demographic trends, Israel, where close to a majority of all Jewish children already live, will emerge as the undisputed center of the Jewish world. Given the below-replacement birthrates among non-Orthodox American Jews, by 2030 Israel could become, for the first time since early antiquity, the home to a majority of all Jews.

Israel’s rise as a technologically advanced state seems to have undermined the economic reasons that at times led Jews, even Israelis, to come to America. The diaspora “Jewish personality,” built around resistance to persecution, minority status, and adherence to tradition is being replaced, as the French sociologist Georges Friedmann predicted nearly six decades ago in his The End of the Jewish People? In its place a distinct new Israeli national consciousness has emerged. “The Jewish people,” Friedmann wrote, “is disappearing and giving way to the Israeli nation.”

Friedmann may have overstated the case, but in time much of his analysis could well be vindicated. The Jewish community in America is showing signs of deep divisions along political lines even about Israel. In a moment of economic hardship, hyperpolarization, racial tension, as well as a troubling rise in white nationalist agitation, there is also declining interest in organized religion among millennials.

This is also a growing chasm between an increasingly left-wing rabbinate that dominates all but the traditionalist Orthodox denominations, and their synagogues’ often more conservative, or at least centrist, members and donors. Liberal and progressive Jewish organizations like the ADL and the Reform rabbinate seem to have little trouble working with figures like Al Sharpton, despite his record of anti-Semitic agitation, or supporting Israel critics like newly elected Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock. Debate over whether to support the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement despite its charter labeling Israel’s treatment of the West Bank as “genocide” and “apartheid” illustrates the tension between what Rabbi Sid Schwarz calls “Tribal” and “Covenantal” Jews.

Sadly, it is Jewish youth who are most caught in the middle, forced to choose between their “progressive” inclinations and their sense of Jewishness. Many are confronted by these apparent either-or choices while attending universities that have become hotbeds for anti-Zionist, and even anti-Semitic, agitation, such as USC, University of California Irvine, the University of Delaware, NYU, and others across the country. Then there are the left-wing organizations that advertise their Jewish identity despite being funded by gentry liberal bastions of the WASP elite like the Rockefeller Foundation—that have joined the intersectional chorus condemning Israel as a racist, fascist, apartheid state while demanding that American Jews purify their religion by falling in line with the progressive party line.

Roots of the Diaspora

A Judaism without a powerful diaspora would be a change so profound it almost defies comprehension. It would eliminate what has been a primary source of Jewish cultural, social and economic progress from antiquity.

At its origins Judaism was a tribal religion built around what historian Ellis Rivkin calls a faith of “utter simplicity.” For a brief time, it emerged as a centralized religion—despite the criticisms of the prophets—controlled by the hereditary priesthood. By the seventh century BCE, Judaism and the political state were merged into one central authority.

Yet even as Judea and Israel flourished, Jews began to disperse. The original Babylonian exile was followed by voluntary migrations to other parts of the ancient world that held better prospects than the narrow confines of ancient Israel. By Christ’s lifetime, more than two-thirds of Jews lived outside Palestine—Alexandria likely had more Jews than Jerusalem—although the Temple remained the center of worship. As today, connections between the scattered Jewish community and Israel were profound. Jewish communities in Parthia and even further away remained major contributors to the Temple in Jerusalem, and also helped finance the Maccabean restoration of Jewish sovereignty in the second century BCE.

With the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the failed Bar Kokhba revolt of 135, and ensuing expulsion, Judaism was transformed into a primarily diaspora religion. No longer tied to the rites of one sacred temple, religious practice was reoriented to the synagogue. Contemporary rabbinic Judaism, “turned in upon itself and upon the Torah,” in the words of the British historian Michael Grant, still reflects the legacy from these events in the first two centuries of the common era.

Large Jewish communities survived for millennia in countries across the world, especially in the Muslim world, where anti-Jewish persecution tended to be less severe than in Christian Europe. But by the late Middle Ages, after numerous migrations and forced exiles, the majority of the Jewish diaspora had settled in Eastern Europe. By 1500, Poland emerged as “the Ashkenazi heartland.” Like the Spanish Jewish culture that birthed the great sage Maimonides, Eastern European communities spawned a vital spiritual and philosophic tradition, including an archipelago of yeshivot. It also birthed the joyful Judaism of the Hasidic movement that is at the core of Chabad. Rabbi David Eliezrie, author of The Secret of Chabad, suggests that the leading Hasidic denomination is “a prime gateway for Jewish renaissance in the United States” and the “strongest evangelical Jewish movement in the contemporary world.”

Despite their rich spiritual and communal life, these mostly poor small-town Jews of the Pale of Eastern Europe lived perpetually on the precipice of disaster. Communities like those in predominantly rural Kishinev, suffered repeated pogroms. By the time of the 1903 conflagration that hastened the mass departure of Jews from the Russian Empire, a half million had already fled the region.

In Europe, most Jews, notes historian Paul Johnson, “accepted oppression and second-class status” as long as they could be left alone. But America proved different. Jews were welcomed by the first British governor of New York for their mercantile skills and trading contacts. By 1776 the American community numbered 2,000 and supported five congregations across the fledgling country.

These communities embraced the newly formed United States, with protections of religious freedoms built into the Constitution. George Washington himself wrote to several congregations that in the new republic “all possess alike liberty and immunities of citizenship”—something that could not be said in most European countries.

In America synagogues, like churches, were “free associations” operating outside government or central communal control.

Legal, and even social equality also accelerated assimilation and intermarriage. By some estimates, according to Arthur Hertzberg’s The Jews in America, one-third of Jewish families present at the time of the American Revolution had left the faith by 1840.

Judaism might have faded from the American story if not for the mass migration of German Jews, estimated at 100,000 by 1860, after the collapse of reform efforts there and the reimposition of restrictions on Jewish business, particularly in Bavaria. These migrants brought commercial skills particularly valued, and often well rewarded, in a rapidly growing country in desperate need of middlemen; prominent entrepreneurs included founders of such firms as Loeb, Lehman, and Goldman Sachs.

Although initially adhering to staid orthodoxy, by the late 19th century many German Jews, led by figures like Isaac Meyer Wise, began to promote Reform Judaism. In these new, somewhat churchlike synagogues, yarmulkes were no longer mandatory, the dietary laws dismissed, and formal educational training introduced for the rabbinate. This loosening of covenantal restrictions seemed to offer the best of both worlds: One could stay loyal to the faith while fully participating in their society—as one contemporary put it, “a man in his town and a Jew in his tent.”

The nature of American Jewry was utterly transformed once again by mass migration from the Russian Empire. In contrast to the then demographic center of the diaspora, America loomed as both land of opportunity and a means of survival. The great composer Irving Berlin recalled how in his native Mogilev province, located in what is today Belarus, a Cossack assault incinerated their village, forcing them into exile: “Creeping from town to town … From sea to shining sea, until they reached their star: The Statue of Liberty.”

Initially the Russian Jews faced considerable discrimination—albeit far less deadly than in the Pale—along with greater liberty. Far less European in manners, with less education and fewer commercial skills than their German counterparts, they stood out in what was still an overwhelmingly white Protestant America. Henry Adams wrote that the presence of Polish Jews “makes me creep” while another titan of the WASP establishment, Massachusetts Sen. Cabot Lodge, was determined to limit Jewish immigration. Anti-Semitic agitation sometimes also came from a more populist direction, notably from rural Southerners, some of whom complained, following the old meme, that “Jewish bankers” were about to turn decent small farmers into “serfs.”

Ultimately, though, the German influence was overwhelmed and Russian and Polish Jews came to dominate in American culture and the popular imagination. By 1965 the descendants of Eastern European Jews outnumbered the Germans almost 8 to 1. Initially they were less able and less willing, than the Germans before them, to modify their religious observance. “The world of the east European Jews,” Irving Howe recalled in his masterpiece The World of Our Fathers, “was a world in which God was a living force, a Presence more than a name of desire.”

Like the Germans, the Jews of the Russian empire hunkered down in crowded big cities, notably New York, home to roughly 45.5% percent of American Jews in 1920 (and 26% of Jews worldwide). Many crowded into the Lower East Side, a place more densely packed at the time than Bombay (today’s Mumbai). In the first generation, and even the second, the synagogue remained the center of communal life even as a secular thriving Yiddish theater and media also emerged.

Increasingly Jews integrated into American society, like other groups, through civic associations. Jewish federations emerged organically in large American cities 125 years ago to centralize community fundraising and grant-making, and provide donors a single campaign to which to send their gifts. Local federations quickly evolved to provide leadership and support community needs. They administered social services, funded Jewish education, fought anti-Semitism, supported both Israel and local Jewish institutions. In civil society, the federations represented the community, and made policy for Jewish organizations within their areas of operations (“catchment area”) before the rest of society and other faiths.

Different federations operated independently and supported a variety of local institutions to include Jewish hospitals, orphanages, homes for the aged, and those with special needs; resettled refugees, and managed individual and institutional support for Holocaust survivors. The size, role and effectiveness of local federations varies widely but overall these long critical institutions, like many others in our society, both Jewish and gentile, have diminished both in numbers and community standing. The collapse of the federations’ influence and reach has been precipitous. Their aggregate number of donors across America had shrunk from 900,000 in 1985 to 450,000 in 2016; and their share in Jewish philanthropy from 79% to 16%.

Not all Jews stayed in the urban ghettos. A minority, typically American in their restlessness, sought out better environments for their families further from the urban core, for example leaving the Lower East Side for less dense Harlem, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and eventually the suburbs. Others trekked to cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Boston, and, increasingly, to the West Coast, with the emerging metropolis of Los Angeles replacing San Francisco as the dominant California center. LA, which had fewer Jews than Buffalo in 1900, emerged by the 1990s as the second-largest Jewish city in the diaspora after New York.

Hollywood came to rival banking and garments as a key Jewish-led industry. For the most part, the studio moguls avoided Jewish topics and embraced WASP standards of morality and often politics. But behind the scenes Judaism, and Yiddishkeit, was “the epoxy,” as one writer put it, holding the sprawling entertainment complex together.

The move to the West Coast was part of a larger movement to places like Miami and other largely suburb-dominated cities. Deborah Dash Moore, chronicler of this internal migration, describes how military veterans, whose service had brought them into contact with the country outside the urban ghetto, drove the relocation of Jews to places, mostly in the Sunbelt, that combined greater economic opportunity with milder weather.

In the postwar years, Jewish geography underwent a dramatic change. In 1960, 46% of all Jews in the United States lived in New York; by 2020, this percentage had fallen to 25%. In 1960, 67% of American Jews lived in the Northeast, while today the number is closer to 44%. Meanwhile, the percentage of Jews living in the South has risen from 9% in 1960 to 22% in 2020; the percentage of Jews living in the West has doubled from 11% to 23%. In the process the suburban Jews reinvented Judaism in ways that revolved “less from tradition than from personal choice.” They did not, as one suburban LA synagogue suggested in the 1980s, have to become “any more Jewish than they are comfortable with.”

Suburban Jews, at least till the 1970s, still tended to cluster among themselves but they had moved up into an elevated tier of ethnic enclaves. In these “golden ghettos,” the more affluent gained living space, enjoyed better weather, and the leisure world of country clubs, cars and swimming pools.

Jewish suburbanization in turn spurred an enormous growth in new synagogues. An estimated $1 billion was invested in temple construction during the decades of the 1950s and 1960s, arguably the greatest building boom in the history of American Jewry. Jews then were joiners: Affiliation with synagogues exploded from 20% in 1930 to nearly 60% by the end of the 20th century, reaching two-thirds in the suburbs. Often synagogue memberships came with access to additional facilities. The so-called “shul with a pool” model fulfilled the 1950s vision of Reconstructionism founder Mordecai Kaplan who called for synagogues to fulfill not only for religious “but cultural, social and recreational purposes.

But the synagogue community center model, which defined the heyday of postwar American Judaism has been coming apart for decades. Between 2001 and 2020, the overall number of traditional synagogues declined by a third across the country, with closures of 20% or more in 34 states. The COVID pandemic, with its prohibitions on in-person gatherings and acceleration of the shift toward digital society seems certain to make this worse. “The many Jewish institutions that rely on attendance, membership dues and other sources of revenue may not be able to hold on until the crisis is over,” wrote David Suissa, publisher of the LA Jewish Journal, recently.

Suburban Judaism is ideally suited to embrace the online shift. Digital religious practice addresses one issue particularly relevant on the periphery—convenience. In dense, urban Jewish communities of the past, and that still exist now, largely in New York, the ability to walk to shul is essential. But in suburbia, notes a recent Atlanta community survey, respondents found that the No. 1 barrier to greater levels of Jewish engagement was time: the “length of time to get there,” “lack of time to attend,” and “programs/activities occur at a time that is not good.”

In suburbs like Orange County, California, home to roughly 65,000 Jews, even large communities are scattered. No city or ZIP code in the county is more than 2% Jewish. Yet after rapid growth through the 1980s, the population has stagnated and many once thriving synagogues are emptying, particularly of young people who are vital to their institutional future, with dramatic reductions of up to three-quarters in the number of Hebrew school students.

The Future of American Jews

If Judaism is to be reenergized it will be in increasingly dispersed communities outside of urban cores, coalescing in the wake of COVID and the current civil unrest. A recent Harris poll found upwards of 2 in 5 American city dwellers are considering a move to somewhere less crowded. The National Association of Realtors reports its surveys show households are “looking for larger homes, bigger yards, access to the outdoors and more separation from neighbors.” Former urbanites are more than symbolically heading for the hills in more remote locations such as the Catskills, Montana, rural Colorado, Oregon, and Maine.

Critically this pattern includes millennials, particularly those with families. Although many millennials, including Jews, move to the inner city in their 20s to early 30s, most have been heading to the suburbs for relative safety, better schools, and homes with yards. In New York, 295,103 change of address requests, each one representing an entire household, were filed with the city from March 1 through Oct. 31. That puts the total number of people who left the city at more than 300,000, an exodus estimated to have cost the city some $34 billion in income.

Suburban home sales are rising rapidly, particularly in Connecticut, while the rural counties north of the city have experienced huge increases in demand at the same time as demand for city apartments drops.

Similarly, although perhaps less dramatic, an outmigration from the Jewish stronghold of Southern California, concentrated in Los Angeles, was already occurring before COVID. This represents potential good news for burgeoning Jewish communities in more economically vibrant places like Phoenix, Dallas, Atlanta, and Houston. With both the New York and LA economies now performing worse than virtually any large metro, this trend is likely to accelerate.

Estimates suggest roughly 1 million Jews out of a total of some 6.7 million in America live in small towns. While small-town Jewry has suffered considerable erosion in the last century, that, too, may soon be changing. Matt Williams, research director for the Orthodox Union (OU) has pointed out that 74% of Orthodox American Jews still live in the tri-state region of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, but are now migrating from bastions like Williamsburg to places like New York’s Hudson Valley, the Catskills, and Lakewood, New Jersey, to find cheaper housing conducive to their way of life in more secure environs. The OU even holds biannual relocation fairs to introduce New Yorkers to Orthodox communities from around the country looking to attract transplants. The number of attendees and the number of attractive destinations has increased in each of the last five iterations. Destinations span the country, including in the West, where La Jolla, Las Vegas, and Scottsdale were represented in the last Fair.

The Judaism emerging from this rapidly changing environment will be far less tied to existing institutional synagogue structures. Shawn Landres, a social entrepreneur and co-founder and former CEO of Jumpstart Labs, speaks of the “unbundling” of the synagogue into its component parts, many of which can now be accessed independently without institutional commitment or expense. This new “modular” shul may be replacing old frameworks, creating new institutions that “reflect contemporary realities and meet the needs of the individuals they engage and serve” rather than those of their founders. More importantly, these new institutions eschew “membership” in favor of “participation” in which “the guarantor of an organization’s long-term impact is neither real estate nor an endowment, but rather network resilience.”

There are a variety of descriptive but derisive terms being used to describe what is rising out of the unbundling of institutional Judaism: salad bar; smorgasbord; a la carte; boutique Judaism; and spiritual grazing among them. But these new nodes and networks of Jewish life play a critical role, particularly serving the poor and newcomers. By “shaking loose institutions and institutional life,” suggests Rabbi Jill Zimmerman, COVID-19 has opened “enormous opportunities to decide what comes next. There is loss but there is the possibility of what could be.”

Once a Beverly Hills-based pulpit rabbi, Rabbi Zimmerman moved online in 2015 when she realized that the dominant membership-model synagogue structure, with clergy on-call 24/7, was unsustainable. Since then, she has been building a virtual community and crafting content to address spiritual practice, mindfulness, meditation and hasidut, teachings of the early Hasidic rabbis like the Baal Shem Tov.

Rather than serving one physical community, she now addresses the spiritual needs of people from around the world, with some virtual audiences as large as 700, in addition to her 39,000 social media followers. In a similar effort, several local rabbis have formed the Jewish Collaborative of Orange County which seeks to address the spiritual needs of local Jews outside institutional settings.

The radical shift resulting from Jews accessing their Judaism online is the decoupling from physical space. Rabbi Marcia Tilchin, who founded the Collaborative, believes that “niche programming that people can access from anywhere will dominate for the next 20 years” and that “there will be no one cultural place people will go for their Jewish infusion when they can go anywhere” online.

COVID is speeding up the development of that new model. The Hartman Institute, whose summer program in Israel usually attracts 150 participants for an immersive learning experience in Jerusalem, pivoted in 2020 to a monthlong online program called “All Together Now: Jewish Ideas for this Moment.” At no cost for participants, “the program drew over 1,000 signups on the first day it was announced in June. By the end of the first week, more than 6,000 people, including some 1,100 rabbis and 600 Jewish community professionals had registered.” And unlike years past, the entire program remains available online.

Rabbi Elie Kaunfer of the New York-based Hadar Institute has enjoyed similar successes. Last year, Hadar’s Tisha B’Av program, which usually attracts 125 live participants, was replaced by an 11-hour online festival that attracted over 900. Hadar Institute has put up over 200 classes totaling 900 sessions since March that have garnered over 25,000 attendances by 7,000 unique individuals. Project Zug, a chavruta matchup that has always been online, is on track to double in participants this year.

But arguably the biggest winner in the digital transition has been Chabad, whose organizational and Jewish identity manages to fuse traditionalism and piety with being a serial disrupter of institutional norms. Rabbi Menachem Posner, staff editor at Chabad.org, says that Chabad has been innovating with technology since before the internet. Early adopters of vinyl records, radio, and television, they were quick to embrace the internet as well. In the 1980s the Lubavitcher Hasidic organization began experimenting with computer bulletin boards and Listservs. They registered the Chabad.org domain on the brand-new worldwide web in 1994, the same year as Yahoo! and well ahead of Google, Facebook, The New York Times, and Wikipedia; and way before Twitter, Instagram, or WhatsApp.

This early embrace has paid off. According to Rabbi Posner, Chabad.org logged 54 million unique visitors last year. Chabad has another domain, Rohr Jewish Learning Institute (JLI), which provides structured, educational content, curricula, lessons, and lesson plans for day schools, lectures, seminars, and home study. There are over 15,000 classes online, accessible through every Chabad center website. The JLI website logged an average 50,000 participants a week before COVID and has increased 25% to 30% since March. The principle that Rabbi David Eliezrie documents in The Secret of Chabad, “if God gives you technology, use it to reach people!” is a primary driver of the organization’s efforts and allows each of its platforms to reach a maximal audience.

The “unbundling” of the traditional synagogue and the rise of online platforms has engendered new bottom-up associations. This entails what will likely be a fraught transition away from traditional institutional loyalty and toward what Alvin Toffler described as an “adhocracy,” which rather than being directed from above will follow a consumer demand model as individuals create their own ways of accessing Judaism.

One example is Atlanta’s Jewish Kids Group, an independent, pluralistic, nondenominational after-school program that offers Jewish education and engagement with a summer camp vibe outside the synagogue structure. Founder Ana Robbins designed a business to serve “all types of Jewish families, including interfaith and unaffiliated.” Its primary market is single and two-parent-working families that need child care and want immersive Jewish learning experiences for their children but aren’t interested in, or can’t afford, day school and also aren’t interested in synagogue environments. JKG launched in 2012 with six kids, and has grown to 300 in five locations across Atlanta that serve a largely a non-temple-belonging constituency. (Full disclosure: Co-author Ed Heyman’s daughter works as a site director for JKG, after teaching Gemara for eight years at a local Jewish day school.)

Like Robbins, Rabbi Dani Eskow, co-founder and CEO of Online Jewish Learning, is also supplanting the traditional synagogue structure by offering online b’nai mitzvah training, Hebrew School at Home, and “anything Jewish a family wants to do online” including adult education and small-group Hebrew lessons. Her online Hebrew school expanded in 2015 when synagogues, facing declining finances and Hebrew school enrollments, asked if she could support or run their programs remotely; she now works with 20 shuls and 40 Jewish educators across America and internationally to create online content delivered to 400 students. “Judaism should fit into your life, not be a burden” suggests the Boston-based rabbi.

Another expression of this shift can be seen in the rapid growth of independent minyans which are “unbound” micro communities formed by and for people who are experienced daveners and know what they want from prayer, sans the encumbrances of traditional institutions. One example is Elie Kaunfer, a rabbi who started Kehilat Hadar in Manhattan in 2001 which helped launch the modern independent minyan model. “Instead of focusing on new ideas,” says Kaunfer, “the Jewish community would be better served by connecting to the original ‘big ideas’ of our heritage: Torah, avodah [worship], and gemilut hasadim [charitable deeds].”

Kaunfer’s model is highly portable, nonproprietary, and easily replicated. It has grown from six minyanim in 2001, to 60 active groups in 36 cities and 19 states around the country and 17 abroad in 12 cities across nine countries. Defined simply as prayer communities, “organized and led by volunteers, (with) no paid clergy or denominational affiliation,” independent minyanim do not offer a radical new form of worship; indeed, their services are almost entirely in Hebrew and hold to traditional liturgy.

Critically, these groups are noninstitutional and lay-run; attract experienced daveners who seek to pray with purpose, as an alternative to the big-tent, lowest-common-denominator institutional feel of the suburban liberal synagogues in which many grew up. As Kaunfer relates, they serve up “a fully traditional liturgy and Torah reading; a commitment to full gender egalitarianism; a short (five-minute) d’var Torah; a lay-led ethos with high standards of excellence; a service that doesn’t drag and engages the daveners through music.” In addition to abandoning establishment structures, the independent minyan model doesn’t conform to “once widely accepted normative standards ... as in-marriage and support of Israel” or an inordinate preoccupation with Holocaust remembrance. These values are not rejected but are simply not the focus. That is not to say that all standards and traditional requirements are ignored. To be counted, a minyan has to have a core of at least 10 people, hold services at least monthly, and not be an adjunct of an existing synagogue. It’s hardly an easy task for busy professionals, many with families, who put a premium on their time, but it’s far easier than paying to fund a large structure, with full-time staff, mortgages and other place-bound obligations.

For those who want intense and immersive study outside the seminary, either as a gateway, supplement, brush-up, or refuge, Kaunfer offers a learning institute in Manhattan that is also accessible online. The Hadar Institute provides the opportunity for lay people to do serious Jewish learning in programs of one week, one month, a summer, or a year, as well as in executive seminars; a multiyear track offers semichah, or rabbinic ordination.

To continue thriving into the indefinite future, Judaism today, as in the past, must adapt to changing conditions. The role of Jewish institutions, most significantly the large communal synagogue, so critical to the movement and integration of newcomers to the society, will never be replaced entirely. Many of the most critical needs, including those of our most vulnerable groups, can only be fulfilled by strong capable institutions with the backing and logistical capacity to care for the elderly, children with special needs, returning prisoners, and poor families.

In the present the core social needs of the Jewish world are filled by two kinds of organizations: One is Chabad, which is expanding rapidly and offers a full gamut of services. But, while it may have far more room to grow, Chabad will never be able to serve the entire American Jewish community and isn’t the right fit, culturally or otherwise, for some less-observant Jews. The second kind of organization is the Jewish Federation with its local Jewish Community Centers (JCCs) that foster social engagement, as well an expansive nonprofit network to provide resources both for the needy and for Jewish families. The problem is that federations are bleeding money, laying off hundreds of employees, and shutting down or merging branches across the country. The collapse is due to long-term structural problems like declining membership and a loss of funding but conditions have been made far worse by COVID.

For those Jews who might once have gravitated toward federation for community and social support, there now exists a large gap. Some may turn to the dynamic Chabad but we are also likely to see the growth of more mission-focused “communities of meaning” such as Rabbi Sid Schwarz’s Kenissa. These groups organize around a mission like education or homelessness, or around a cluster of causes, with the organizational agility to scale up and down based on members’ needs.

Over time, many synagogues will have to downsize or even close altogether. The Jewish Community Legacy Project is doing a booming business planning contingencies for synagogues, federations, and foundations facing challenging circumstances—they are currently assisting 61 communities, 14 of which have closed, 13 of which have legacy plans in place; and are working with 20 federations and 10 community foundations. The warning signs are often all too evident: declining congregational membership, increased average age of members, shrinking religious school enrollment, leadership responsibilities falling on fewer and fewer people.

Yet despite the spreading institutional crisis, the potential for revitalizing American Judaism is significant. Past societal traumas among Jews and other people of faith, have led to “spiritual reawakenings.” There are signs that this is happening now. According to Pew, one-quarter of Americans say the pandemic has bolstered their faith, a finding also confirmed by Gallup. The next generation of Jewish youngsters may not be lost. The future of the diaspora, as historian Grant suggested, is far from over. It will persist, and even thrive, but only to the degree that it does what previous generations have done: innovate and change to meet a rapidly changing environment. In flexibility, as well as faith, lies the people’s future.

Joel Kotkin is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. His new book, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, is now out from Encounter. You can follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

Edward Heyman is currently active as a volunteer and consultant in the Orange County, California, Jewish community, following a career as a partner in a software development firm serving the defense and intelligence communities.