The Pope and the Mysteries

This pontiff—and the one before—and what’s left of Rome

The previous pope made more sense to me. He wanted to reposition the Catholic Church in a modern world that has not been favorable to the Church, and one of his ways of doing so was to argue with people. This did not give him a favorable press, but it made him a force, intellectually speaking. He was keen on taking up the terrorist challenge from the Islamist movement. He blundered in how he went about it in a famous lecture at the University of Regensburg and afterward had to go apologize to the entire Muslim world. But it was good that he raised the argument. He worried about totalitarianism. His most impressive thought was to accept the fact that, in Europe and perhaps elsewhere, the Catholic Church has shrunk into a minority religion. And, having accepted, he found, in the pages of Tocqueville, an advantage. The America of the 1830s that Tocqueville described in Democracy in America was a Protestant country and a liberal democracy, but it contained a small Catholic minority, whom Tocqueville described as principally poor people. This meant the Irish immigration, perhaps together with French Canadians on the American side of the Canadian border. Tocqueville considered that America’s Catholic Church was doing a good job of standing up for those people, which was to the benefit of the country as a whole. And the Church was maintaining an alternative approach to spiritual matters.

Benedict XVI saw in this an inspiration for the Catholic Church of our own time, at least in Europe. He wanted the Church to be a thread in the modern liberal tapestry, instead of waging a constant losing protest. Was there something to this idea? Or did it amount merely to a new disguise for the never-ending war against the liberal sexual reforms of the 1960s, as some people thought? The modern spirit of sexual honesty was hard on the Church in Benedict’s time. Still, his attraction to Tocqueville was attractive.

Pope Francis during his American tour just now said all the right things to indicate that he, too, affirms the principles of liberal civilization. In Philadelphia he extolled the Founding Fathers. In Washington, D.C., he invoked, among other heroes of history, Martin Luther King, Jr., whose name may trip awkwardly off a papal tongue. But I wonder how political liberalism fits into his larger imagination. Almost everything I saw in the press introduced the pope to us as a kind of Greeting Card expressing the simplest of sentiments, kindliness, generosity, tenderness toward children. Or he was presented as a figure within the American political debate, in which he was deemed to be practically a member of the Democratic Party: friendly to the immigrants, favorable to climate policy reform. Or he was deplored for not rebuking the pederasts more sternly, or for not bringing women to the pulpit, or for maintaining a traditional line on marriage—to which he himself responded by trying to stay out of the line of fire. He kept secret his meeting with Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refuses to certify gay marriages. But I would imagine that, in the pope’s thinking, the American political controversies figure as secondary concerns, about which he can choose to speak in any number of tones, according to a strategy based on other considerations entirely.

Francis is not, after all, someone who has risen in life on a basis of liberal or left-wing political ideals. The Argentina in which he spent most of his life was dominated in one fashion or another by the populist dictator Juan Domingo Perón, who derived his own principles in large part from Francisco Franco, the caudillo of Spain; and, indeed, Francis appears to have begun his political life, to call it a political life, in some kind of friendly relation to the Peronist group the Iron Guard, which stood on the extreme right. Anyone interested in reading about this might want to look at an essay just now (“Pope Francis, Perón, and God’s People: The Political Religion of Jorge Mario Bergoglio”) by my old friend Claudio Iván Remeseira, once upon a time of the Bueno Aires Nación, lately of New York.

Remeseira tells us that, during his early Jesuit years in Argentina, Father Bergoglio took his place within Argentina’s right-wing version of Latin American Liberation Theology, known as the Theology of the People, a descendant of the old Catholic Integralism of France. This was a movement dedicated to maintaining the solidity of society against the atomizing effects of liberalism. The solidity of society meant sympathy with the poor. But it also meant a respect for social hierarchies, with everyone in his allotted place, and a supreme place for the Church—all of which made for a comfortable fit with Peronism, or would have done so, except that Perón allotted the supreme place to himself.

Everyone evolves, and no large institution on earth has evolved more dramatically or admirably during the last 50 years than the Catholic Church.

By rehearsing these facts I do not mean to imply that Pope Francis is a reactionary wolf disguised as a liberal sheep. Everyone evolves, and no large institution on earth has evolved more dramatically or admirably during the last 50 years than the Catholic Church; and the Argentine Church and its Theology of the People are said likewise to have evolved, in keeping with the reforms of Vatican II. Doubtless Francis has evolved. What have been the stations of this evolution, though, and how far has it gone? At what moment did Generalissimo Franco cease to be an inspiring figure, and Thomas Jefferson become one? Is Francis, too, a student of Tocqueville? It would be wonderful to think so.

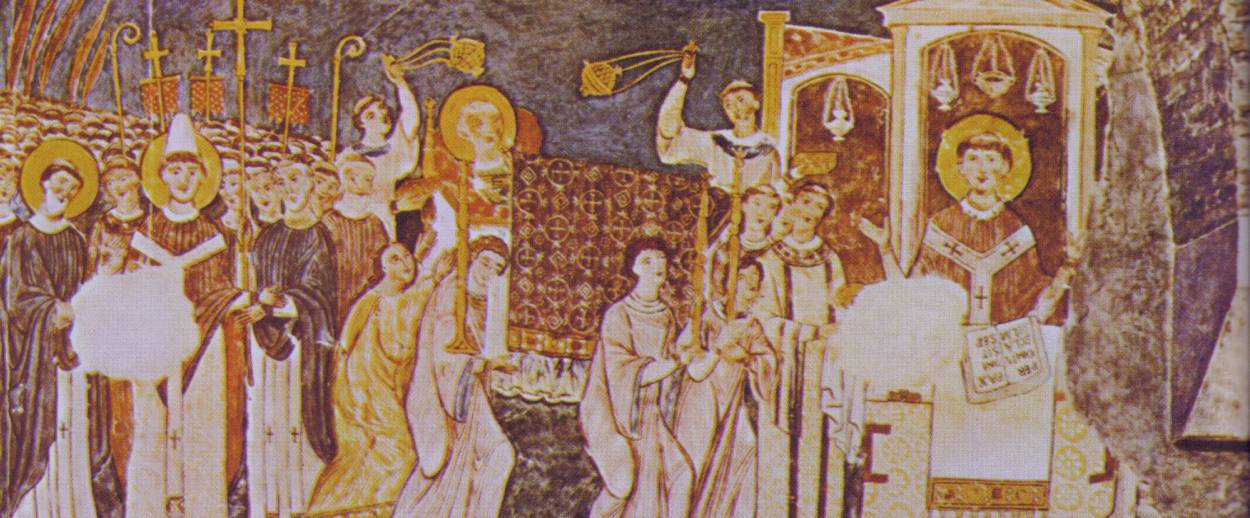

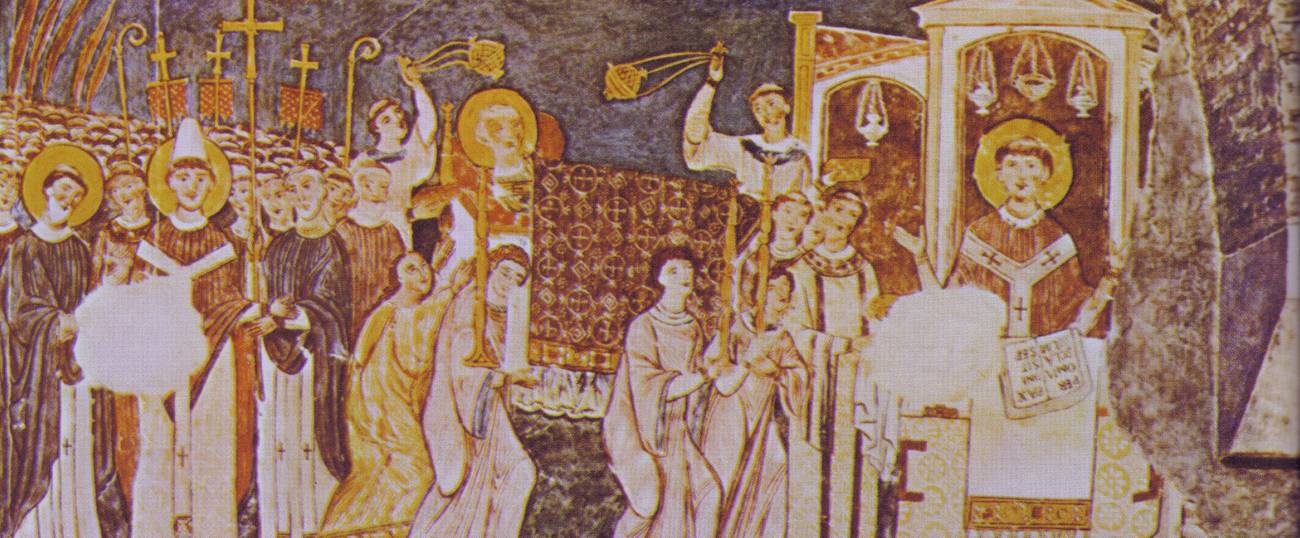

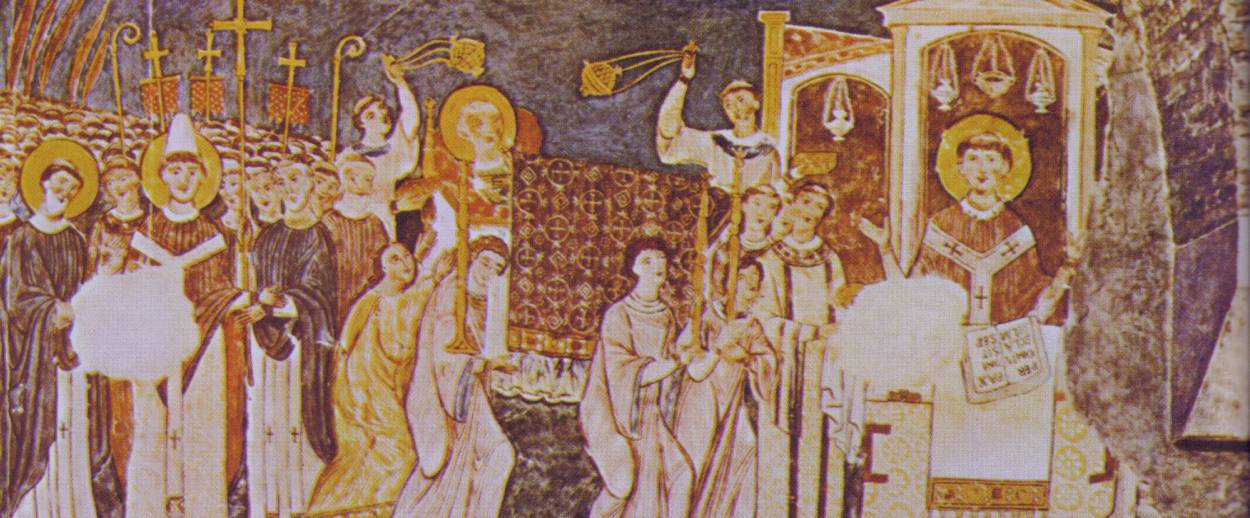

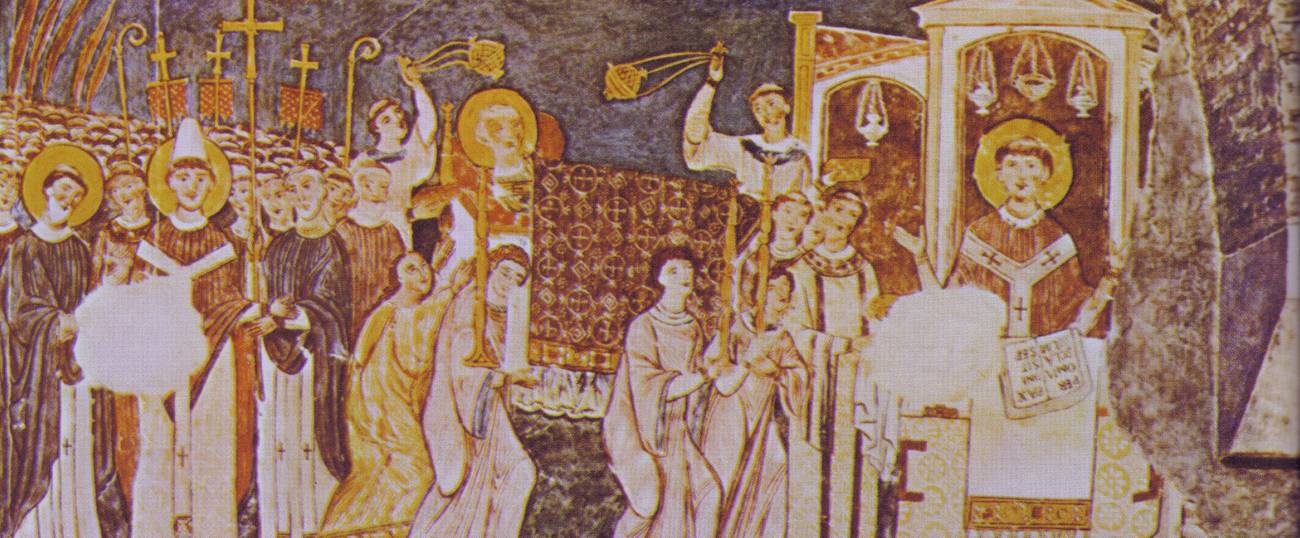

The idea of maintaining the Catholic Church as a counterculture has always seemed to me, in any case, an attractive project, for reasons having nothing to do with the left-right political wars and the sex-and-gender issues—attractive, I mean, even to us non-Christians. It is sometimes said of Chateaubriand, the author of The Genius of Christianity in 1800, that he was drawn to every aspect of the Catholic Church except its Christianity; and I find this understandable. In modern society it is the Catholic Church that most assiduously cultivates the memory of ancient Rome and its civilization—the Roman arts and their medieval legacies, and the Roman philosophical doctrines and their own legacies. The idea that some corner of modern culture is devoted to maintaining those particular legacies seems to me immensely moving. Now and then I read that a 100-year-old church in Brooklyn or the Bronx or some other American place is about to be sold to real-estate developers, and I become nearly as agitated as the half-dozen elderly parishioners who are sorry to see their old temple get torn down. The exterior architecture of those churches is often of merit, and, whatever the quality of the interiors and the statuary and artwork may be, I regard those buildings as temples to temple-ness. They house whatever is left of Rome.

There are certain people from the American literary past of, say, 90 years ago, who inspire in me the same appreciation—Edna St. Vincent Millay, for instance, whose Catholic touches add a note of mystery to her bohemian charm; or F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose occasional hints of Catholic mysticism make up his most brilliant aspect; or the Catholic-atheist philosopher (if you are a philosopher, you are able to come up with novelties like Catholic atheism) George Santayana, who was marvelous at conjuring the thrills of neo-Platonism and marvelous at rendering the mystic thrills compatible with a modern scientific outlook. Those people, the American writers of the 1920s and thereabouts, knew how to conjure two universes at once, the ordinary one in front of us, and the invisible one that occasionally winks at us from behind a column. Isn’t the ability to conjure a double-layered universe the beating heart of a Catholic counterculture for the modern world? Here is the living memory of the Roman mysteries, its pulse still faintly detectable.

Everyone prefers to talk about politics, I know. Even so, I warily doff my normally anti-clerical cap to Benedict XVI’s Italo-Argentine successor, and I wish him luck and continued progress along the modern-but-ancient path.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.