This Sunday, 350 guests will gather at the Sephardic Temple in Cedarhurst, Long Island, to enjoy live music and feast on traditional Jewish cuisine from Greece and Turkey—tarama (fish roe salad), fasolia (green beans in tomato), bamyas (stewed okra), and raki and lokum (Turkish delights) for dessert—and celebrate the centennial of a pillar of New York’s Sephardic community: the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America. While the celebration will be an opportunity to honor the organization’s past and present, there is also a sense of uncertainly about its future: engaging the next generation of the Brotherhood is integral to its success.

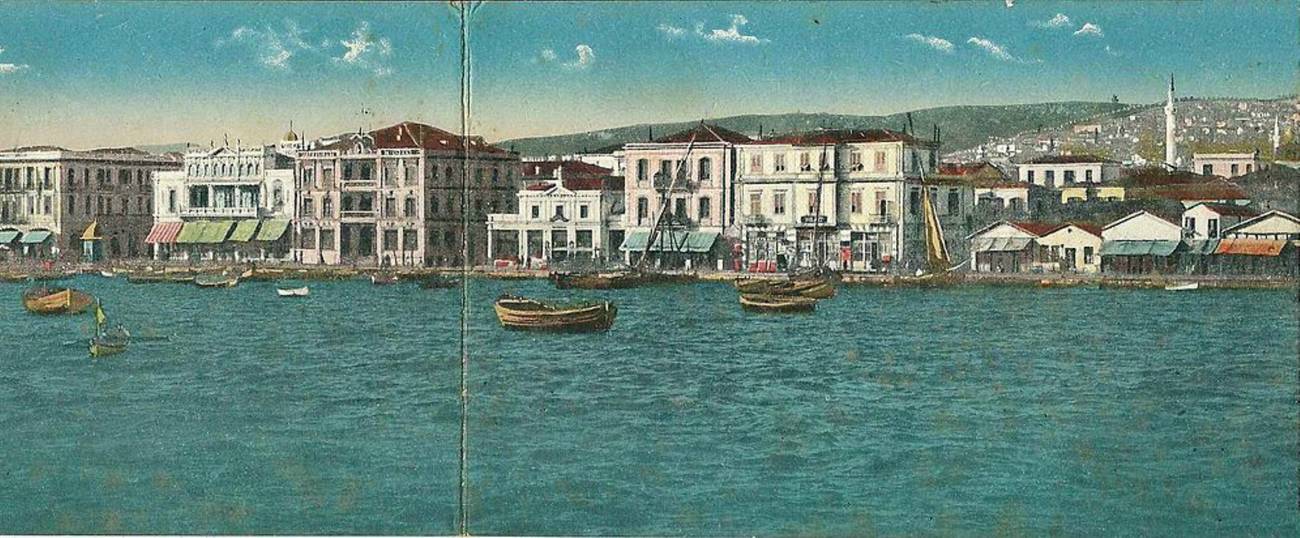

In 1915, a group of 40 young Jewish men and women from Salonica—a city in today’s northern Greece (now called Thessaloniki) that was once home to the largest and most dynamic Ladino-speaking population in the world—convened at a café on the Lower East Side of New York City. There, they established the Salonican Brotherhood of America, or La Ermandad as it’s known in Ladino, which they incorporated in 1916. My family joined after arriving to America from Salonica in 1924; my great-grandfather served as a rabbi for the Brotherhood’s synagogues in Harlem and later New Brunswick, New Jersey, where, in the Brotherhood cemetery, five generations of my family are buried.

In order to create a broader sense of community, the organization changed its name to the Sephardic Brotherhood of America in 1921 to welcome all Sephardic Jews of Ladino-speaking background in New York. It fulfilled a need for some of the 50,000 Jews from the former Ottoman Empire who came to the United States during the early 20th century but did not receive a cordial welcome from already-established Yiddish-speaking Jews and were often not recognized as Jews. One satirist, writing in the Sephardic Home News, questioned: “How could you be a Jew when you looked like an Italian, spoke Spanish, and never saw a matzo ball in your life?” Sephardic Jews attempted to “prove” their Jewishness by showing off their prayer shawls and books, the Hebrew lettering of their Ladino newspapers, or even their circumcisions.

Seeking to combat this sense of isolation not only by providing financial aid help to needy members and arranging burials like other immigrant societies, the Brotherhood also hosted lectures on language, culture, and history, while publishing its own annual magazine in Ladino (El Ermanado, or “The Brother”). The Brotherhood also financed Jewish philanthropies in Salonica, and, after the Holocaust, funded weddings for the few Salonican Auschwitz survivors and sponsored visas for some of them to be able to come to America. The Brotherhood became a model for dozens of other Sephardic organizations created in New York and across the country. But after the war, with their home communities decimated by the Holocaust, the Brotherhood focused on its own aging members and founded the now-defunct Sephardic Home for the Aged. The Brotherhood, essentially, became a burial society.

In 1947, a dozen other organizations established by Jews from Turkey and Greece merged with the Brotherhood to create the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America. For Bernard Ouziel, an attorney with family roots in Tekirdağ, Turkey, who has been SJBA’s president for 35 years, the organization is about the joy of community, getting together in a non-religious setting to chat over “social soul food” like borekas (savory pastries) and kezo blanko (feta cheese). But he sees the Brotherhood facing another crossroads: The younger generations is fully Americanized and don’t have the same sense of nostalgia. The future, he said, is uncertain—a membership of 2,500 families in the 1970s, now hovers around 1,500—so he’s looking to the organization’s new executive director, Rabbi Nissim Elnecavé, to set a vision for the future.

Elnecavé, who is from Mexico City with family roots in Salonica and Izmir, wants the Brotherhood to help the younger generations reclaim a voice, to “lift up the pride of our members and of our people—los muestros—not an arrogance, but just an ability to feel good about who we are.” He says that Jews with family roots in Turkey and Greece have internalized a sense of their own inferiority vis-à-vis Ashkenazim and resigned themselves to the fact that their story would marginalized in the American Jewish narrative. While they have a sense of pride in private, he said, they don’t have a prominent public profile, not even like other robust non-Ashkenazi Jewish communities, like Syrians in New York or Persians in Los Angeles. “It’s time for that to change,” he said

Elnecavé sees technology as an asset. He has created a new online newsletter, La Bos Sefaradi (The Sephardic Voice), and is building a website that will feature podcasts, Ladino poetry recordings, a database of Hebrew and Ladino liturgy, and a YouTube channel with programs such as “Nona’s cooking.” The Brotherhood is also renewing its overseas outreach by connecting with Turkish Jews to facilitate student visas or other opportunities in America, especially given the tense political climate in Turkey. It also continues its scholarship fund, which distributes $40,000 to college students annually.

The future of the Brotherhood, according to Elnecavé, lies with the participation of the younger generations, such as the Marcus brothers. Third generation members of the Brotherhood with family roots in Veria (near Salonica) and Izmir, Ethan, a 20-year old Princeton student, helps with web development. With his brother, Andrew, a 24-year old graduate of Hunter College who works for New York City, they recently founded the Greek Jewish and Sephardic Young Professionals Network, supported by the Brotherhood and the Greek synagogue on the Lower East Side, Kehila Kedosha Janina. The Network hosts meetings that attract 30-50 people in their 20s and 30s: holiday parties, cooking classes, happy hours, Shabbat dinners, and even a meeting with the Greek Consul General. The events tend to accommodate those who may not participate in an Orthodox-style Sephardic synagogue and may also have Ashkenazi heritage.

Andrew sees the Brotherhood as poised to “maintain, perpetuate, and reinvent Ottoman Sephardic identity” for the 21st century. Because it is not a synagogue and not limited to a building or set agenda, the Brotherhood, Marcus said, can again play the role of a unifying, umbrella organization to promote a shared heritage and vision for the future. He hopes that the centennial celebration will spark the Brotherhood to reassert itself, to restore a sense of family, and to introduce “a new phase in Sephardic American life.”

To that we say, azlaha y beraha! (Success and blessing!)