The Shoah’s Other Lost Children

What will the opening of sealed Vatican archives reveal about the fate of Jewish children hidden by Catholic communities during the war?

On March 4 of this year the Vatican announced that it would finally open the papacy archives of Pius XII, the pope whose tenure from 1939 until 1958, covered the years of the Second World War. This step has been a long time coming and historians hope that it will finally shed light on the actions taken by Pius XII and the Catholic Church as Jews were being rounded up and slaughtered in Europe by Nazi Germany and its collaborators.

“The Church is not afraid of history,” declared Pope Francis, the current leader of the Vatican, of the decision to open the previously secret archives to the public. And, indeed, in the years since the war the Catholic Church has taken measures to publicly confront its own long history of institutional anti-Semitism. Starting with the Second Vatican Council in 1965, the Church officially condemned anti-Semitism and absolved Jews of the charge of deicide, formally renouncing the charge that they bear any collective guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus. But those steps toward atonement and reconciliation do not actually illuminate the Vatican’s role during the Holocaust, a period of contested history during which, critics say, Pius XII veered between inaction and complicity toward the crimes of the Nazis.

Foremost among the lingering questions that Jewish leaders hope will be resolved by the newly opened archives, are the names and birthplaces of Jewish children placed for safekeeping with Catholic families or Catholic institutions (monasteries, convents, schools) during the war. Many of those children were converted to Catholicism, an act that may have helped save their lives. But prominent Jewish leaders like Abraham Foxman, former head of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), believe that even after the war, when it was safe to come out of hiding, most were not told they were Jews. In many instances, the children were the only members of their families to survive—but there were other cases where surviving relatives did exist, and sought in vain for the remnants of their devastated families.

At the end of World War II, with Europe in chaos and its Jewish communities all but destroyed, Jewish priorities, of necessity, focused on the immediate physical needs of the survivors. Yet Jewish leaders already knew that thousands of frantic parents, barely a step ahead of the Gestapo and its collaborators in Poland, France, Belgium, Holland, and elsewhere had placed their children in the care of non-Jewish neighbors, employees, convents, monasteries, Catholic schools, and orphanages in the hope that they would survive. Motivations varied among those who volunteered to become the guardians of this lost generation. Some people took in Jewish children out of individual charity and human decency or because they felt compelled to do so out of communal responsibility, while others sought to profit from a desperate situation.

Some 1.5 million Jewish children were murdered during the Shoah and fewer than 100,000 in all survived, many because they were hidden by non-Jews, according to the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). By late 1945 and early 1946, Jewish organizations, largely led and funded by the JDC, estimated that around 10,000 of those survivors were in Catholic institutions or with non-Jewish families, and set out to find as many of them as possible.

Among those who made it their personal mission to find these children, was Rabbi Itzchak HaLevi Herzog, Israel’s first chief rabbi, father of Israel’s late President Chaim Herzog, and grandfather of Isaac Herzog, the current chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel. According to The Rabbinate in Stormy Days: The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Yitzhak Isaac HaLevi Herzog, Chief Rabbi of Israel, by Shaul Mayzlish, Rabbi Herzog met with Pius XII in early 1946 and demanded that he cooperate in finding the children and returning them to the Jewish community.

Although the pope did not issue a bull—as a public decree from the papacy is known—his cooperation in the transfer of some children from monasteries and Catholic families to the care of assistants for Rabbi Herzog is documented in Rabbi Herzog’s papers. Though some assistance from Pius XII was recorded, the available historical records don’t show exactly how much the pope knew about the status of the lost children or whether the Catholic Church under his direction took any measures, formal or informal, to prevent converted children from returning to the Jewish community.

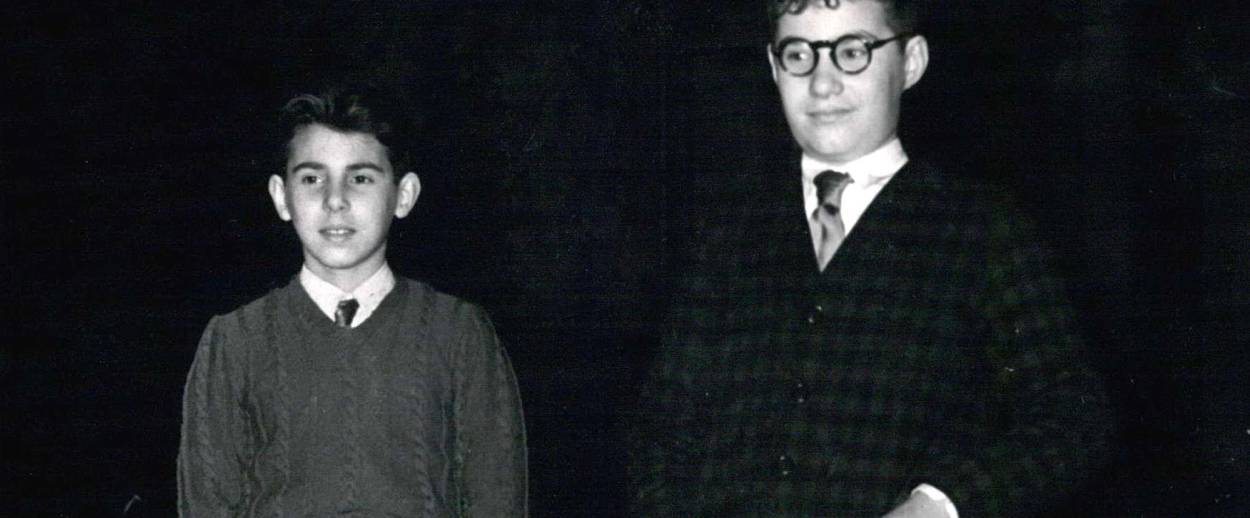

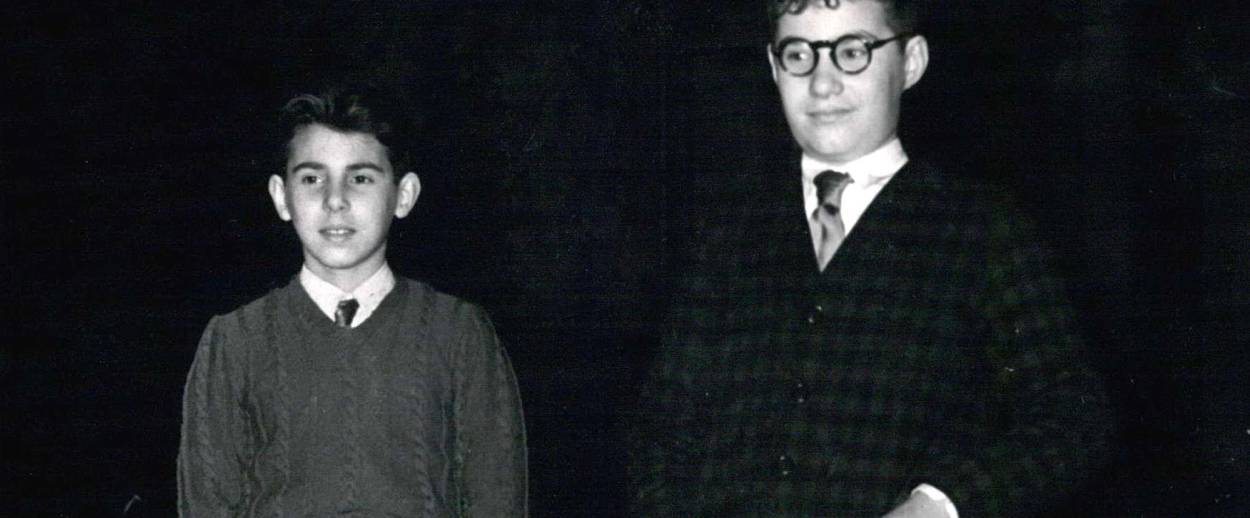

A number of attempts by surviving family to recover children ended up in court and were well publicized at the time. Probably the most famous was the story of Robert and Gerald Finaly. The two children, whose parents were deported from Grenoble, France and murdered in Auschwitz, were sheltered by their Catholic babysitter. But attempts by a surviving aunt to get them back after the war turned into a case of kidnapping and intrigue involving officials of France’s church. Eventually, the children were returned to their aunt and were brought to Israel where both, aged 78 and 77, live today.

L’Affaire Finaly shook France as a whole and reverberated through Europe’s shattered Jewish communities, still recovering from the horrors of the preceding years. The academic Suzanne Vroman, author of Hidden Children of the Holocaust: Belgian Nuns and Their Daring Rescue of Young Jews From the Nazis, has said that the fear of “hundreds of Finaly Affairs,” discouraged Europe’s Jews, who were deeply reticent about becoming the center of public attention from advocating publicly for the cause of the lost children.

Still, there are many other notable cases of Jewish children who were reunited with their families after the war. Abraham Foxman, the high-profile former president of the ADL, is one example. Foxman’s father successfully fought to regain custody of his son from the Catholic family that had sheltered him during the war. Another is Father Romauld Waskinel, born Jakob Weksler. Weksler was hidden with a Catholic family in Poland during the war and didn’t discover his Jewish parentage until he was an adult. He now lives in Israel and is no longer a priest.

In a telephone interview, Foxman told Tablet that he believes there were many more saved, hidden children than have yet been brought to light. “We are losing hundreds of Jewish children every day,” Foxman said, referring to those who after being sheltered during the war never learned of their true origins and will die without knowing their birth families or their connection to Judaism. “It’s hard to impugn Church motives during the war,” Foxman added, but, “afterwards might be another issue.”

Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the New York-born Chief Rabbi of Poland, gets hidden children coming to Warsaw’s Nozyk synagogue several times a month these days. Some have discovered they were born Jewish as the result of a deathbed confession of an older relative, while others make the discovery through other means. Schudrich views the Vatican announcement as a hopeful sign, and one that “needs serious academic examination.” But there are also “moral questions,” he said. “What do we do with the information if we get it? Do we or don’t we have an obligation to tell people?”

The opening of the Vatican’s sealed archives will not provide all the answers, or definitively one of the darkest chapters in Jewish and world history, but it may, as Rabbi Schudrich alluded to, allow us to begin asking new questions while there is still time.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Toni L. Kamins is a freelance writer. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Daily News, Times of Israel, and many other publications. She’s the author of the Complete Jewish Guide to France and the Complete Jewish Guide to Great Britain and Ireland (St. Martin’s Press).