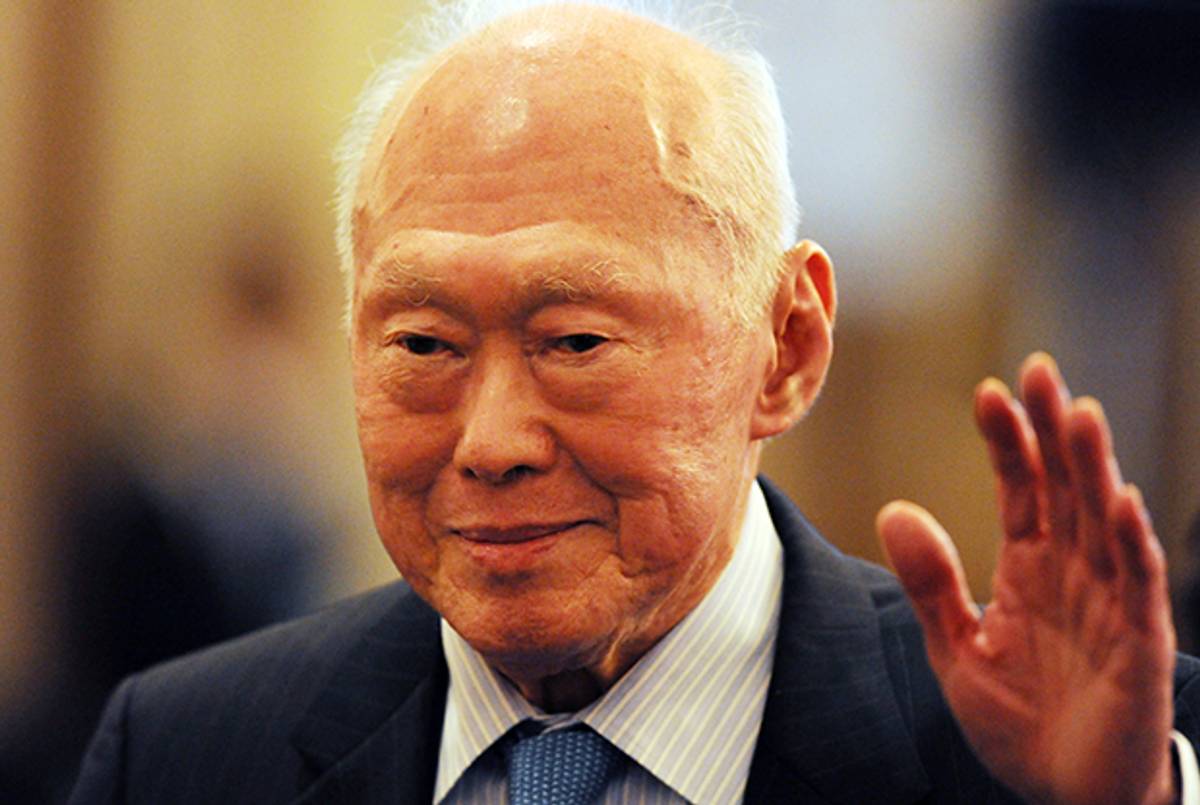

The many obituaries, remembrances, and panegyrics that have appeared in response to the death of Singapore’s founding father and long-serving prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, at age 91, hit all the major themes. As most tell it, Lee, who died Monday in the Singapore hospital where he was being treated for pneumonia, was a legendary statesman who, by downplaying human rights and multiparty democracy, pushed all the chips of his legacy onto the table of development.

The wager paid off. Visitors to 21st century Singapore, seeing its spotless boulevards and thriving financial hub, can understand why Lee titled one of his memoirs From Third World to First. But what many of the appraisals fail to mention even in passing is one of Lee’s biggest gambles ever: His decision to follow in the footsteps of Israel.

No other country in Southeast Asia more closely resembles Israel than Singapore. There is the geography: small and surrounded. There are the historical tensions over religion and ethnicity: Singapore’s main religions are Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam. The majority of its citizens are ethnic Chinese, but there are also ethnic Malays and Indians, creating a pot that doesn’t always melt. Finally, there is the security focus: Singapore places a heavy emphasis on its military.

In 1965, when Singapore was voted out of Malaysia and had, in the words of Lee, “independence thrust upon it,” the country was weak and vulnerable to attack. It doesn’t take that large of an army to conquer a sliver of land roughly 270 square miles long. Relations with neighboring Malaysia were at a low. Singapore needed help. Israel’s government, ever ready to score points in the war of hearts and minds against the Arab world, rose to the challenge.

A few months after independence, in December 1965, Israeli advisers arrived in the country to begin training a group of officers and soldiers that would form the core of Singapore’s nascent army, according to a 2004 Haaretz investigation.

The historian Jacob Abadi writes that Singapore decided to make military service compulsory for males starting at age 18, based on Israel’s system. Singapore also created its own reserve force using the Israeli model, and military advisers from the Jewish state trained new recruits to Singapore’s Armed Force Training Institute in 1966. In 1967, according to Abadi, Lee said Singapore had studied what smaller countries surrounded by large neighbors do to survive, and “opted for the Israeli pattern.”

With predominantly Muslim Malaysia and Indonesia nearby, Lee had to be careful. As Abadi and the Haaretz report explain, the Israelis were officially presented as agricultural advisers from Mexico.

Though the intimate military cooperation ebbed as Singapore established stronger contacts with Malaysia and other states uncomfortable with its close ties to Israel, the state of Singapore’s military today—considered one of the most advanced in Southeast Asia—is a testament to continued similarities and an ongoing relationship.

Take Israel’s focus on its Air Force, which Singapore emulated. Robert D. Kaplan notes in his recent book about the South China Sea, Asia’s Cauldron, that while Singapore has only 3.3 million citizens, its Air Force is the same size as Australia’s.

But what the two countries ultimately share—beyond passionate admirers and passionate detractors–is an unlikely existence. At the beginning of his memoir, Singapore Story, Lee explains why he wanted to write the book in the first place. His words will likely resonate with Israelis.

“I thought our people should understand how vulnerable Singapore was and is, the dangers that beset us, and how we nearly did not make it.”

Joe Freeman is a Southeast Asia-based journalist whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Foreign Policy, The Guardian, The Christian Science Monitor, The Phnom Penh Post, and the Nikkei Asian Review.