A genial, enthusiastic exponent of the glories of entrepreneurship and innovation, Steve Blank is widely recognized as one of the godfathers of Silicon Valley. Selected by Harvard Business School as one of America’s “masters of innovation”—he has the cover story in this month’s Harvard Business Review—he started eight tech companies including E.piphany. After cashing out nicely at the top of the 1990s dot.com bubble, he became the Johnny Appleseed of the “lean start-up movement,” whose gospel he spreads by teaching classes at Stanford, Columbia, and Berkeley, and other public lectures, and by leading entrepreneurship seminars in China, Eastern Europe, and other places where he is treated like a rock star.

What separates Blank from so many of his wisdom-dropping peers in the Valley is the path he took to get there. His genius didn’t come from knowing the right people at Stanford or Harvard in the middle of the tech boom and then loading up on stock options. He made his money the hard way, if not exactly the old-fashioned way: He dropped out of college, loaded race horses onto airplanes in Miami, joined the Air Force at the height of the Vietnam War, and then went to Thailand. The work he did there led him into the “black world” of CIA and NRO-sponsored companies that worked on super-secret high-tech projects for the U.S. government, which have since offered him unique insight into the Silicon Valley miracle.

In addition to being a mensch, Blank knows as much about Silicon Valley—the official history, the secret history, the personalities, and the distinctive culture of innovation and entrepreneurship—as anyone alive. It was a pleasure to meet him for dinner recently on the Upper West Side of Manhattan before a series of lectures and seminars he gave at Columbia University.

What follows is an edited version of portions of our conversation about the history of the Valley, secret and otherwise, his own equally colorful personal history, and the role of Jews in the tech business.

Your parents split up, your dad disappeared, you got thrown out of Michigan State, and then you went into the U.S. military at the height of the Vietnam War. Now in your late middle age you are one of the godfathers of Silicon Valley. How does that work?

If you come from a dysfunctional family, it gives you an enormous competitive edge in entrepreneurship because you can bring order out of chaos—because while everyone else is melting down, it feels like a typical day for you.

The bad part is that when things start becoming repeatable and normal you throw hand grenades into your own organization and become destructive. It takes a couple of years and some therapy to figure this out, but it’s important for a healthy personal and professional life. Some of us recognize it later, and some of us never recognize it.

I know that your father had a grocery store in Chelsea. Where were your parents from?

This is a bizarre story, and I never understood it until maybe 10 years ago. My mother came over when she was 9 from a town outside of Vilna. My grandmother met my grandfather as he was passing through town, in what my mother described as a “love affair”—meaning he knocked her up and then left for the States promising he would sent her a ticket. Instead he was sending her enough money not to come to the States. But if you ever met my grandmother, she was pretty tenacious, and when my mother was about 3, she was getting letters from her cousins in the Lower East Side, saying, “This guy is living with someone else, you better get over here.”

So, my grandmother saves money and goes to some port with her cousin. And just as they get to the hill, my grandmother remembers she left some of the gold still buried in the village. So, they go back when my mom was 3 years old, its August 1914, and World War I starts and then the Russians invade Germany, and then the Germans invade Lithuania, and they don’t get out until 1919, smuggled out in a hay cart. And when they get to Ellis Island, my grandmother wrote my grandfather, “You will meet me here.”

So, my grandmother and my mother move in, my grandmother doesn’t speak English, not a word, but she realizes there’s another woman living with her. So, my grandfather goes to work the next day, and her second day in America, my grandmother rents a pushcart, takes not only her stuff but my grandfather’s clothes, and gets a new apartment, and says, “Congrats, we’re now a family.”

Wait; it gets better! My mom grows up on the Lower East Side, and she meets my father who came when he was in his late 20s—my parents meet in a Socialist Workers Party Dance, they were garment workers, ILGWU. My dad and his father (he was the oldest of seven) come over to work, and he meets my mother—but he was supposed to make money to bring over to the rest of the family in Poland. So, he tells his parents, and his mother writes a letter in January, 1939 saying, “Don’t worry you can always do this another time.” Then Hitler marches into Poland, and his father blames him for killing the rest of his family.

So, my sister and my parents lived in Chelsea, on 23rd and 8th, and by the time I was born they owned a grocery store. Then they opened a second store in the Bronx and quickly lost it. Then they bought a house in Douglaston near the LIE and 61st avenue, and then my parents got divorced when I was 6. My father ran away to Israel with a woman who looked identical to my mother. It was really bizarre. She was 4’10” and blonde.

An Israeli?

No, she was an Argentine Jew, who for all I know might have been a German in disguise. I think I saw my father once after that. Between living at home and going to Israel, he lived in San Francisco, and from age 6 to 17, all my mother used to call him was “the bastard.” But when you’re a teenager, it doesn’t matter what your mother says; she can’t be right. So, I hitch-hiked across the country to find my father, and guess what! He was an idiot!

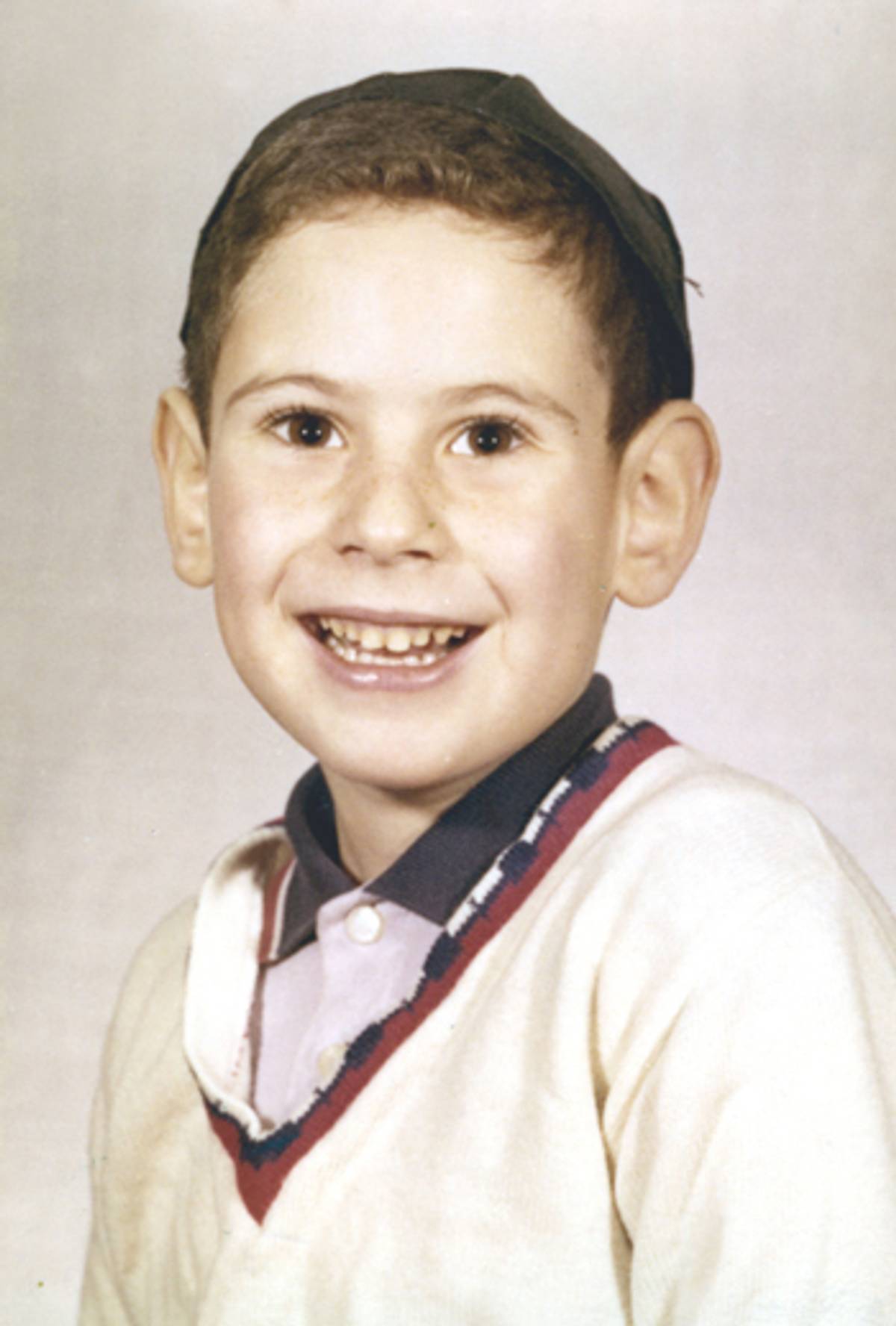

You went to the North Shore Hebrew Academy? What was it like back then?

I don’t know if this was standard or not, yeshiva was half day Hebrew, half day English. I went through fourth grade. I didn’t know a single world of Hebrew. When my girls were bat-mitzvahed I was like, “How do you read this stuff? I can’t remember a thing!” I hated that school. Actually when my kids were small, I went back and found it. A) it looked a lot smaller than when I remember it, and B) it still looked like a nutty, Orthodox school.

I’m curious about why you joined the U.S. military at the height of the Vietnam War.

When I was in high school I was thought of as a stupid kid. There were smart kids and stupid kids and my sister said, “You know, you’re not stupid. You just learn differently.” But I never did a day of homework. My mother was never home. She was a bookkeeper and went out dancing every night; I have no idea what she did. I raised myself, essentially.

My sister ran away from home when she was 16. She was great for me when I needed it though. She said, “No, you aren’t dumb. There’s an organization called Mensa, just take the test for me.” It was at Herald Square, I took the exam and she was pissed because I had a better score than she did. It gave me some confidence. I still remember the last year in high school I got four 65s and one 98. The 98 was in the first computer class they offered in high school. And then they used to give this thing called the Regents scholarship test, so I took the test, and I’m looking for my name in the bottom, I’m there 30 minutes looking for my name until I found it, and I was third in my class. I got a scholarship to SUNY. I didn’t want to go to Buffalo, so I chose Michigan State to be a pre-med.

What was a “computer” back then? And why did you leave school?

Punch-cards. It was just a notion of being able to control a device.

As for why I left, I had a girlfriend my first year in Michigan State, and I’m on scholarship and she’s working her ass off. Here I’m screwing around, not really interested. She says, “Why are you wasting your time? Some of us are working our asses off. You ought to leave!” And I said, “How far can I go?”

So, I hitchhiked to Miami. The next-to-last ride I got down there was from some guys in a Volkswagen Beetle, and they gave me their phone number and names just in case something didn’t work out. I went to visit my friend and he said, “I hope you aren’t staying because I just threw out the last guy who was on my floor.” So, I called up the guys in the Beetle, and I stayed on their couch—and they turned out to be Buddhists. The next morning I woke up to chanting, and then when they were done they told me there was a job at the airport and asked me if I wanted to come. So, I started working at the Miami International Airport loading racehorses onto cargo planes.

There I got interested in the avionics on the planes. I would take home manuals and ask the guys, “Where do you learn this stuff?” They said they learned it in the air force. I ended up joining the military and went through a year of training in Mississippi. Everybody was getting assigned to Thailand, Vietnam, whatever, so my turn comes up, I get assigned to—Miami. So, I go back to Miami, and I’m placed at the Homestead Airforce Base. I was there a week, and our chief said, “Hey, listen; they’re calling for volunteers in Thailand. Any volunteers?” In the military the rule is you don’t volunteer for anything. But who the hell wants to be in Miami. I want to go to Thailand!

So, I volunteered to go to Southeast Asia, which turned out to be the best thing I ever did in my life.

How long were you there?

A year and a half. I worked on fighter planes and wild weasel. By the time I left Thailand I was supervising 15 other technicians. I was good at pattern recognition, and fixing things is pattern recognition. After a while you see enough stuff, you have enough data, and you know the odds of fixing something.

Were you strictly military in Thailand?

When I was in the air force I was strictly military. At my first company in Silicon Valley, I went to Korea and another undisclosed location as a civilian.

How did you get spotted into the black world track?

So, you’re not going to believe this, but they’re all accidents. My accidents happen through volunteering; I show up for a lot more than most people. “80 percent of life is showing up,” I think that’s a Woody Allen line—but it’s absolutely true. So, when I came out to Silicon Valley I was working for a company in Ann Arbor, and they said, “Well, the valley’s in San Jose”—and I remember our secretary got us tickets for San Jose, Puerto Rico. Because no one had heard of Silicon Valley.

So, I go out there, and the first night was surrealistic. We get off the plane me and another engineer—a Palestinian from Dearborn. The company we were with was so cheap we had to share a hotel room. We’re driving in the rental car and all of a sudden an ad comes on the radio—scientists, engineers, Intel is hiring! So, it’s Sunday and I buy this newspaper called The San Jose News, and for some reason it’s thicker than the Sunday New York Times. I still remember 48 pages of help wanted ads. Then we turn on the TV and see more help wanted ads.

I take in all this stuff, and it’s the blizzard of ’78 in Ann Arbor. Why the hell would I go back? So, I interview all week and get a job as a lab technician, and I fly back to quit, drive out to California and get to my new job, and they told me the guy who hired me was fired and he had no authority to give me a job. The entrepreneur in me thank god, said, “Well, are you hiring for any jobs?” And the poor HR woman took pity on me, and she said you could talk to a new manager in the department, they’re looking for a new training instructor. I go, “I taught before in the military … not really … but sure, absolutely!” And the guy said, “You’re hired!”

So, all of a sudden there are three 40-foot vans full of electronics, and I have six weeks to produce a 10-week course. I don’t even know what a course is, other than I took a lot of them. Well, I did a damn good job, I was promoted to the manager training of education, and then I got to work on this project that took me to these special locations. The special locations happened to be the most secret Cold War project the U.S. ever had.

Talk about between the nexus between the intelligence community and Silicon Valley, and how that evolved.

During World War II there was a guy named Vannevar Bush, who was head of engineering at MIT, and he had a brilliant idea. He had some experience working with the Navy in World War I, and he said we have the military developing advanced weapons—but forget it, they’re clueless. So, why don’t we do something different? Why don’t we draft scientists and engineers, keep them in their own universities, and have the military task them, and let them develop the weapons there? No country had ever done this before: Let’s give the money to the universities and not to the military labs. Basically, they draft 10,000 scientists and engineers and keep them in non-uniform. One of the projects is called the Manhattan Project, which is run by Oppenheimer.

But the other things were they set up 15 separate divisions, radar, electronic warfare, rockets, etc., and they poured the equivalent of $5.5 billion into universities. MIT gets a billion and a half, Harvard and Columbia 350 million, and Stanford gets 6 million. One of the labs was set up at Harvard called the radio research lab, which was a fake code name for a new type of electronics called electronic warfare.

What happened was the Germans had decided to defend occupied Europe from American and British bomber attacks with radar. They deployed over 15,000 radar sets and they had this amazing electronic air-defense system, but we had no idea what that was. So, the first thing we had to develop in less than nine months was the entire electronic intelligence business. We fitted airplanes with receivers, and then we had to build mechanical and electronic devices to shut down the radars. The guy who ended up running this lab was named Fred Terman, and he was an electrical engineer out of Stanford.

And after the war, Terman goes back to Stanford and becomes dean of engineering, and he decides two things: First, Stanford will never get fucked out of military money again. Second, I just ran a war center and the U.S. is now in a cold war, so it will be good for the country to build electronic intelligence in Stanford. So, as the Korean War breaks out and the Cold War ramps up, Terman turns Stanford into a secret weapons lab for the CIA and the NSA. So, Stanford becomes the center of excellence for electronic warfare, which happens to be what I’m working on in Vietnam.

I didn’t realize any of this until later, of course, when I checked into my office at Stanford in the Terman Engineering Building.

So, NRO, CIA, were all working through cover organizations based in Silicon Valley in the 1960s and ’70s and helping to create what becomes the hub of the computer business and the software business.

ESL, Argo Systems, had all the overhead stuff. Back in the ’70s there maybe five or six companies in the valley. At 24 I was accidentally working in the company in charge of training and operations. And it gets even weirder.

Two stories. One, I’m now at this secret, secret, site that’s so secret they don’t even lock the safes because if you’re there, you already know. And because I’m curious and like to read and I love nighttime, I always worked the midnight to 8 shift. Instead of reading a novel, I started on one safe and started reading my way through, keeping a notebook of everything I was learning. I was the guy who did Wikileaks without Wikileaks, but I wasn’t leaking anything—I was writing it down for myself.

I was the guy who did Wikileaks without Wikileaks, but I wasn’t leaking anything—I was writing it down for myself.

And this is when I get impressed with security: Back then I had a big Jew-fro, I swear I’m ¾ of the way through the safe, and I’m really learning a lot of interesting things. We were doing stuff you wouldn’t believe. To make a long story short, I get called in by the head of security for coffee. He said, “How are you?” I said, “Great.” He pulls out an envelope and goes tap, tap, tap, and three long black, curly hairs come out. He goes, “This was found in [name of manual you shouldn’t be reading]. Is this yours?” I said, “Oh yeah, I’ve been reading through all the manuals and keeping all these notes.” He said, “Where!” I said, “Oh, they’re in the bottom of the safe.” He was out of the room, into the vault. He brings back the notebook and starts looking at the code words and is like, “I can’t read this! And you can’t write this!” And I said, “Well, I did.” He said, “Why are you doing this?” I said, “Oh, it was great!” About a week later he said, “I want you to know how much trouble you caused. I have to have your word that you’re going to take up a new hobby.” I thought I was going to get in trouble, but instead they just asked me to take it down a notch.

The black world was completely segregated from commercial activities in the Valley. I think I’m one of the few refugees from the black world into the white world, only because I happened to have a roommate who was working at Control Data, and we knew other guys doing crazy stupid little Apple things and microprocessors. I mean they were a joke compared to what I was working on, but they were masters in their own fields.

Here I was working on projects that were hundreds of thousands of people, big national projects, but these other entrepreneurs were doing stupidly simple things, but it was their own ideas. And I found that a lot more interesting.

It strikes me that you came from this intensely urban and insular New York Jewish world, and then you end up in a series of places—Michigan State, Thailand, the NRO/CIA black world, Silicon Valley, none of which were exactly hotbeds of Jewish life.

I’m in the middle of Thailand and every so often you saw an officer and if he was a pilot it was cool, but any time there was an inspection you’re worried. Some general decided to inspect one day, and the guy steps in front of me and says, “Son, are you Jewish?” I look, and its Gen. Goldberg. I said “Yes, sir.” He said, “Step over here,” and I go, “What?” He says, “What the hell are you doing in the military?” I didn’t know what to say. I was so naïve, I didn’t understand there were no Jews around me; I was having too much fun.

When I started doing start-ups, I think it was Fortune who described me as a “sharp New York business man.” And my COO who was the biggest WASP ever said, “I think they just called you a Jew in Fortune.” But I never thought of it as an ethnic thing. I thought of it as an aggressive New Yorker thing.

So, you’re there, at the legendary homebrew computer club in the Valley, the place where what we think of now as the Valley really gets started, and there’s this kid named Bill Gates, who just started a company called Microsoft. And he sends his famous letter around to all the hobbyists, explaining that there is a thing called copyright, and in fact he’s not going to share his stuff for free with the community, because he wants to get paid. Was that a turning point in the culture of the Valley?

I was a hardware guy at the time. I was interested in what people were doing, and it was silly stupid stuff compared to what I was working on, but it was more about the culture. I was more getting the gestalt of: There’s something happening here, and I don’t want to be on the wrong side of history.

The most famous photo of the pay-it-forward community is a pre-Apple Steve Jobs who had found the chairman of Intel in the phone book in 1974. His name was Robert Noyce. The man founded Fairchild and Intel and helps invent the microchip—he was like the head of Facebook, Google, and Yahoo! all in one. Noyce was 55, Jobs was 24, and there’s a picture of them having dinner with Noyce clearly bemused, and he became Jobs’ mentor. And when Jobs was CEO he never made a big deal of it, but he mentored Zuckerberg, and a whole generation of Silicon Valley CEOs. It’s an understood, underground thing you don’t talk about. It’s kind of like Tikkun Olam, the Tikkun Olam of Silicon Valley. A good mitzvah.

We articulate it because we teach it and because I have to explain it to foreign visitors. But it is really missing from other cultures. It grew up because it was a necessity, and it didn’t exist on the east coast. You owe it to the next generation.

I should mention here that I own the record for the shortest interview with Steve Jobs ever. My best friend worked for Steve Jobs for many years. When they were at Next, Jobs went through 15 VPs of marketing, and my friend connected us. So, Jobs used to love to take walks for interviews, so we go for a walk and we’re maybe 100 yards into this and I realize that he is the biggest asshole I’ve ever met, and he doesn’t want a head of marketing, he just wants someone to do what he wants them to do. I was thinking “What a jerk, I would never work for him.” And then Jobs goes, “What do you say we turn around?” Because he had come to the same conclusion.

In hindsight, he was the best head of marketing, but my ego couldn’t carry it at the time. In his 13 years of exile, he turned from a kid who thought his shit didn’t stink and grew into a great manager.

But take me back to pay-it-forward culture. Why here? There are so many geographically distinct business cultures, like the oil business in Dallas and Houston—why don’t they have a pay-it-forward culture there?

Because most of them are zero-sum games. In Silicon Valley it was, “I can win and you can win.”

You don’t agree that Bill Gates changed that?

It’s very funny. I think you can compare Bill Gates to the open-source community. There are two models. One is the Bill Gates model, and the other is the open-source model, and they seem to co-exist just fine.

How long have you been married to your second wife? Do you have kids?

Twenty-two years. We have two daughters. My youngest goes to Bucknell, she’s a junior. My oldest is working on being an OT.

Why was it important for you to them to be raised as Jews?

When I was growing up, my mother’s younger brother, who I met once in my life, “married a goy.” It was in the 1950s. My mother didn’t talk to him because he was disowned by the family. His kids were my age, and they were growing up in California with no religion at all. I thought, how wonderful!

But then I met his kids when they were my age, and they said it was the worst thing that ever happened. They had no identity. This was like finding out my father was an idiot. It was the same type of shock; finding out a belief I had for a decade was just false.

Fast forward two decades later, I’m having a baby, and I go, “I think I care.” My wife isn’t Jewish, but she didn’t care that much and we agreed to raise them Jewish. So, we had Shabbos and they went to Hebrew school, my wife did the Shabbos candles. She didn’t convert, but we raised them with an identity.

On a different note, when you look at the Valley today what do you see? It has changed dramatically.

Number one is information density. If you think about it, 30 years ago the only way you got info was during one-on-one meetings. You knew very little, and the world knew very little. We just know a lot more now.

Number two, the entrepreneurial culture is now explicit rather than implicit. Back then, people didn’t have computers in their houses, and no one knew about Silicon Valley.

Great entrepreneurs are revolutionaries. They change the status quo. They rebel against what exists. It is only this country and this culture that allow us to do this.

The good news about being retired is I got to be this hand grenade in entrepreneurial education. There’s a nonprofit called Startup Weekend, taught in 109 countries. I’m on the board, and there’s an insatiable demand for this worldwide. I’ve now taught in Finland, Prague, Berlin, and many other places. In every country I’ve been in there’s a distinction between entrepreneurship everywhere with what does it take to ignite a cluster, it takes risk-capital culture, which doesn’t quite follow entrepreneurial culture.

When you went to Israel it was with your kids?

No, I went to Israel with my wife, no kids there. We spent two weeks in Egypt, right before the riots. Now I recommend to everybody that if you want to appreciate Israel you go to Egypt first, and then you kiss the ground when you get to Ben Gurion Airport. After four days, we called up the girls and said you’ve got to get on a plane and come here. So, we spent three days in Tel Aviv, and we went all over the country.

Do you have any contact with Israeli tech entrepreneurs?

I can’t stand Israeli entrepreneurs. They are New Yorkers without grace!

If you look at the early names of tech, it’s all about Vannevar Bush and Terman, and Hewlett and Packard, then Gates and Jobs. Now the big names are Zuckerberg and Brin. Is there suddenly this Jewish moment in the Valley, and is there any cultural reason for that?

No one thinks of them as Jews.

Do you?

No, never.

So, now that I say it—hey, they’re Jews!—is there any way in which they are distinct in that culture?

No. It’s not an accident but no one thinks of them as Jews. Again, I’m not colorblind, but I am ethnic blind. When I came out to Silicon Valley in ’78 it was white-shoe WASP-y venture capital. There was no diversity. Fast-forward 30 years, half the CEOS are Asians and Indians. The glass ceiling is now women. And there are almost no African Americans or Latinos.

So, if an 18-year-old kid came to you and said they wanted to do what you do, namely start a bunch of companies, and bank a few hundred million dollars while doing work that she loved, what advice would you offer her?

Volunteer for everything. Join a startup. I had a career of apprenticeship. I’m a very slow learner with a long memory. Kids overthink their first job. That’s what I tell my students now, there’s no permanent record here. You get to do multiple jobs. Whatever you do, you ought to love to do it when you get up in the morning. For decades I remember driving into multiple jobs, thinking maybe this is the day they figure out how much I love working here, and that I’d do it for free. I couldn’t believe they were paying me a lot of money to do what I love.

Great entrepreneurs are revolutionaries. They change the status quo. They rebel against what exists. It is only this country and this culture that allow us to do this.

***

For more Tablet Q&A by David Samuels, including conversations with Sam Harris, Noam Chomsky, Scott Ian, and others, click here.

David Samuels is most recently the author of Seul l’Amour Peut Te Briser le Coeur, a collection of his writing about America, to be published in September by Seuil.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.