On December 5, 1962, comedian Lenny Bruce, who by that time had been blacklisted at clubs around the U.S., performed at the Gate of Horn club in Chicago. Bruce, then 37, was a large influence on a 25-year-old George Carlin who was in the audience that day. At one point during the show, a reportedly plain clothes cop stood up and said, “show’s over ladies and gentleman, everybody have a seat.” According to Carlin, the police began to check the IDs of the audience members so they could catch underage attendees at Bruce’s racy show, and get the club in trouble.

“I was good and juiced by the time they go to [me,]” said Carlin. And when it was his turn to hand over ID, Carlin told the authorities, “I don’t believe in ID.”

Carlin was thrown in a paddy wagon, and Bruce was arrested on obscenity charges—for saying “fuck” and “tits.”

Ten years later, on May 27, 1972, George Carlin recorded his Class Clown album, including the legendary “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” track. In Carlin’s book, Last Words, he writes about his state going into the show, and the recording of the album:

I had to say to myself, “I want to be sharp and clean and clear tonight. No cocaine.” My diction on it is remarkably lucid. In other words, I was already using enough cocaine that I had to think consciously about not using it to record an album.

A year and a half after Carlin’s gig, a father and his 15-year-old son heard Carlin’s routine on the radio, which set off a legal storm that continues to influence the media in our lives, and even the role of parenting. Here’s The Atlantic, on the series of events Carlin’s routine set into motion:

…in Santa Monica, John Douglas was driving with his 15-year-old son back to New York from a college visit at Yale University. It was an early Tuesday afternoon in 1973, the day before Halloween. Douglas, a CBS executive and a member of a pornography watchdog group called Morality in Media, was flipping through the radio when he landed on 99.5 WBAI-FM. Paul Gorman, the host of WBAI’s “Lunch Pail” afternoon program, warned listeners that he was about to play Carlin’s “Filthy Words” bit, a modified version of “Seven Dirty Words” recorded on the Occupation: Foole album, and that some of the language could be deemed as offensive. Douglas kept the dial on WBAI. A month later, Douglas filed a complaint with the FCC, calling the monologue “garbage.” “He was the funniest comedian of his generation,” Douglas told the Chicago Sun-Sentinel in 2008, shortly after Carlin’s death. “I didn’t turn him in. I was turning in WBAI.”

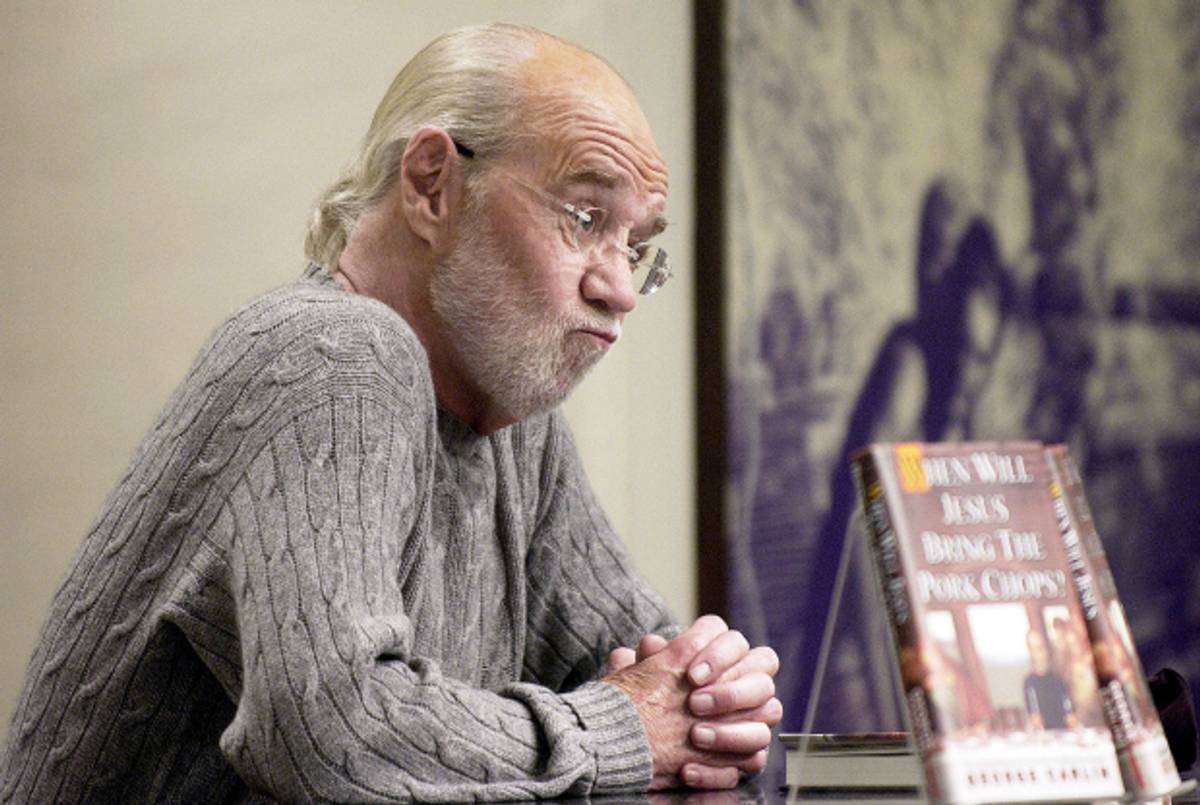

Upon receiving the complaint from the FCC, Pacifica Foundation, the broadcast company that owned WBAI, called Carlin “a significant social satirist of American manners and language in the tradition of Mark Twain and Mort Sahl,” defending the station’s airing of “Seven Dirty Words.” But the FCC upheld the complaint. Though it did not punish Pacifica, the FCC issued the foundation a warning that said, “in the event subsequent complaints are received, the Commission will then decide whether it should utilize any of the available sanctions it has been granted by Congress.”

Shortly thereafter, Pacifica won an appeal at the D.C. Circuit Court to overturn the FCC’s original finding; the court said the FCC didn’t have the right to regulate WBAI broadcasts. No one knew what would happen once the case made its way to the Supreme Court in April 1978, especially when the Justice Department switched its support from the FCC to Pacifica and President Gerald Ford’s Supreme Court nominee, Justice John Paul Stevens, arrived on the court. In July 1978, almost five years after John Douglas heard Carlin’s bit driving back from Yale, the Supreme Court upheld the FCC action in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation in a 5-4 decision. The majority decision stated that the FCC was justified in deciding what’s “indecent,” saying the Carlin act being was “indecent but not obscene.” The Court ruled that because Carlin’s routine was broadcast on the radio, during the day, it did not have as much First Amendment protection. The Court saw Carlin’s language as an invasion of privacy against listeners without warning. The FCC could regulate offensive content on broadcasts between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., the Court said, because a child could accidentally be exposed to harmful profanity.

Listen to Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words” routine here, or watch below:

Related: Lenny Bruce Everywhere

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.