Save American Democracy, Eliminate the Voters

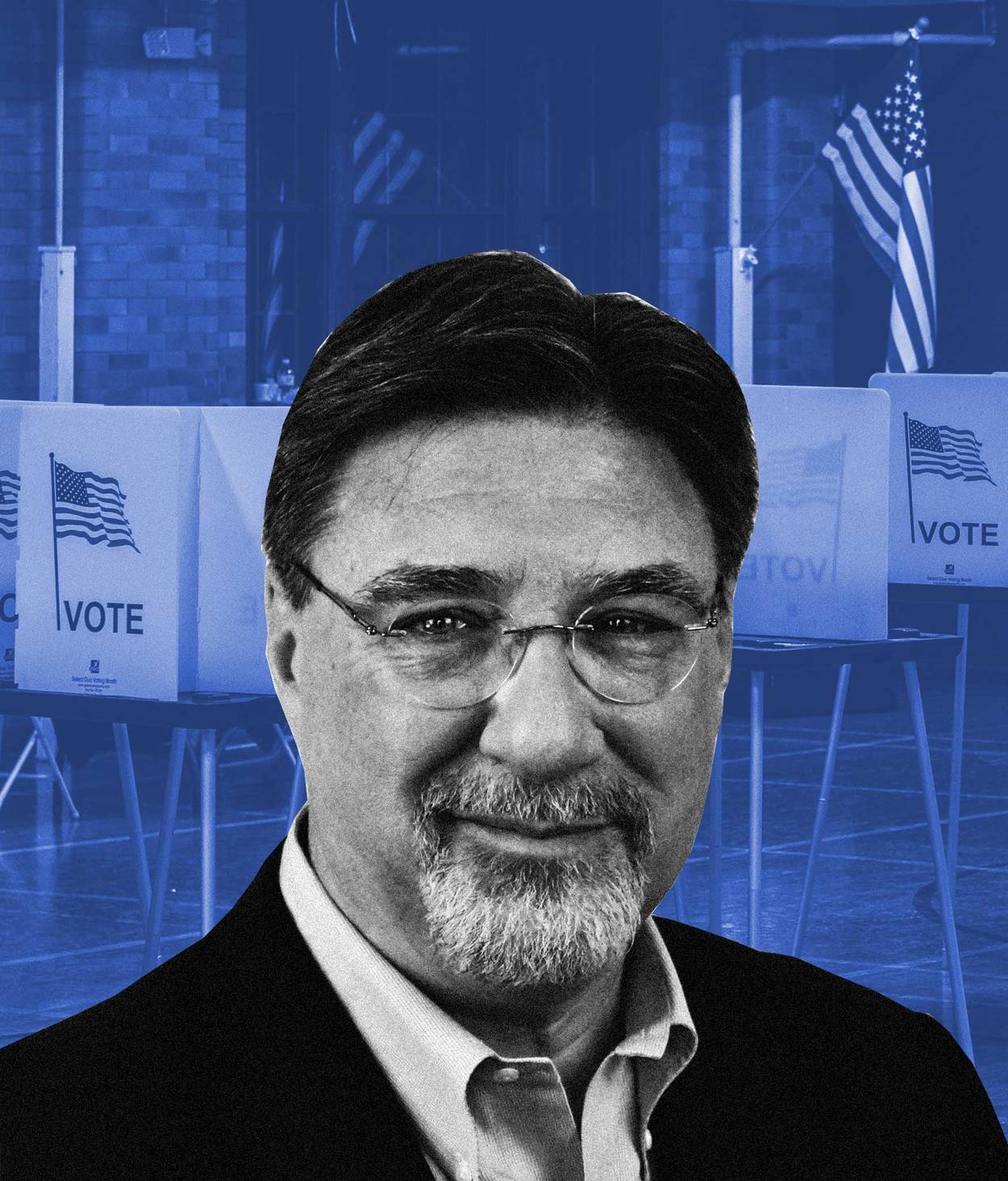

Certified expert Tom Nichols has a ‘moral scolding’ for the plebes

Traditionally, a preference for the views of a small number of people with special knowledge over a larger number of ordinary voters has been seen as anti-democratic. I don’t mean to use the term pejoratively; some people like democracy and some people don’t. Plato didn’t like democracy. He was a brilliant guy. Tom Nichols’ new book makes it clear that he thinks the problem with American democracy is all the stupid and ignorant voters. Would Plato approve?

A “Never Trump conservative” whose specialty is national security and nuclear arms, Nichols has taught at Georgetown, Dartmouth, Harvard, and the U.S. Naval War College. He writes popular books for university presses, like the 2017 title The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters, which examined ordinary people’s unfortunate resistance to experts and expertise. A recent Nichols article, “Afghanistan Is Your Fault,” exemplifies the political style that made him a well known “resistance” figure in the Trump era. In his new book, Our Own Worst Enemy: The Assault From Within on Modern Democracy, Nichols excoriates the masses for a second time. We must, Nichols argues again, find a way to save American democracy from Americans.

Nichols tries somehow to present his view as one that’s supportive of democracy, not opposed to it—indeed, as one that may help us save democracy in its hour of great need. Here is the central subject of his book, as he sees it: “If we believe democracy has failed us, we should first ask ourselves whether we have failed the test of democracy.” It’s a trivial observation that democracy would work well with a perfect populace, since anything would work well in that circumstance. For democracy to fail it must be the case that “we” have failed.

Indeed, Our Own Worst Enemy is peppered with so many internal tensions and contradictions that it’s hard to believe it’s not an attempt to use paradox to convey some sort of secret, true meaning. For Nichols, it’s not just that the problem with democracy is democracy. It’s that there’s a society-threatening crisis, which is that people think there’s a society-threatening crisis when there isn’t. There’s a bunch of people ruining our political system, and their problem is that they think there’s a bunch of people ruining our political system. Populism is a “‘compelling’ narrative, and like all compelling narratives, it has some elements of reality in it”—but at the same time, “populist leaders have to ramp up white-hot rhetoric . . . lest the public doubt for a moment whether they should believe what they’re hearing or seeing with their own lying eyes.”

So who are you gonna believe, huh? Voters who only care about their own self-interest are ruining America, but the same voters are also so driven by resentment that they can’t recognize their own self-interest. Nichols has a chapter on how corrosive narcissism and anger are, but his whole book seems spittle-flecked and he frequently breaks the flow of his exposition to narrate his own expert credentials and accomplishments. Nichols castigates people for “exchanging paranoid memes on Facebook” right after saying that “the rest of us are vigilantly scanning the horizon . . . for the shock troops of a mass movement,” and right before claiming that “authoritarianism could arrive . . . on little cat feet, quietly establishing itself while the rest of us are busy watching television, staring at our phones, and speaking to our friends and family through emojis.”

A series of tiresome tirades written for an audience assumed to be sympathetic and admiring of Tom Nichols, Our Own Worst Enemy consists of 200 pages of bluster, with little explanation of its core assertions and little argument for the connections it makes among them. Poor editing worsens this impression: Elementary errors in spelling and grammar errors give the book the feel of an online rant. An anecdote from the first chapter is retold in the fifth chapter, with the same analysis and even the same jargon. Of his lectures on the moral failings of stupid and slovenly nonexpert Americans, he writes that he is “more reticent to deliver such sermons these days” (he means “reluctant,” but reticence would have been nice).

Our Own Worst Enemy has five chapters. The first argues, Steven Pinker-style, that the world is getting better—even if its ungrateful inhabitants refuse to acknowledge their good fortune. It’s getting more peaceful: no more world wars, no more Cold War, and fewer hot conflicts across the globe. The wars of anti-terrorism may, Nichols magnanimously allows (he was among their louder advocates), have been somewhat misguided in the end, but Americans sacrificed very little for them compared to other conflicts—mere trifles, really, which presumably includes the tens of thousands of American men and women who were killed or maimed in the course of their service overseas.

The world is getting more affluent, too, Nichols writes—it just doesn’t feel that way, since inequality is also rising, which doesn’t matter because inequality is rising only because the rich are getting richer faster than the rest of us. Things don’t seem so great right now because Americans have undergone “hedonic adaptation.” We’re used to how good things are and won’t be satisfied unless they get even better—we’re all so unhappy now because of how darn happy we all should be! For Nichols this seeming paradox is not a matter just of economics; we should also be grateful that we have all these new gadgets, smartphones, and streaming television to amuse us. In the end, “Democracy is not in danger from new tribulations, but from new achievements: Democracies, it seems, cannot cope with peace, affluence, and progress.” Good times create weak men and weak men create hard times, and so on.

The second chapter mimes Edward C. Banfield. In the 1950s Banfield, a political scientist, visited a small Italian town where nobody ever seemed to do anything for anybody else, and where there were no active civic associations. The town was plagued by amoral familism: People only cared about themselves and their own families, not for others. Nichols goes on to say that modern Italians only possess “the liberty of servants” and agrees with an Italian scholar that they have “servile souls.” He raises, though he doesn’t endorse, the notion that this “moral weakness” is “just how Italians are.” Filthy Italians! Non ti sopporto più! Isn’t this a bit like the United States, Nichols wonders?

Oddly, Nichols seems to blame voters for not agreeing with each other more. He criticizes “the standard trope” that “voters are consistent and moderate while politicians are opportunistic and extreme.” Instead, Nichols says, voters have a bunch of crazy views that only look moderate on average. In fact, I think this Nichols chestnut is right, and it in fact it explains why a standard critique of moderation or “centrism” is wrong. Nichols’ twist on this idea, though, is that it is the voters’ fault that they are now led by people he considers charlatans, like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Nichols, a political scientist, does not acknowledge the fact that it is precisely the lack of correlation among voters’ views that is supposed to buttress the decision-making of the group as a whole, as established way back in 1785 by the Marquis de Condorcet in a formulation well known to experts in the field as the jury theorem. Nichols is able to justify his finger-wagging by failing to distinguish ways in which individual voters would be rational participants in democracy from ways in which a democratic system as a whole would be rational.

The fact that many voters can’t be neatly boxed in evokes real fury in Nichols. Nobody comes in for as much of his ire as Sanders-Trump voters and Obama-Obama-Trump voters. But coherence comes in degrees, and Nichols never really explains why Sanders-Clinton or Obama-Obama-Clinton voting would have been more coherent than the other options. He also doesn’t explain why voter incoherence is so worthy of criticism. Pundits, political parties, and politicians themselves often change their views. Why is crossing party lines—something Nichols himself did in the Trump era—so crazy? And why is it irrational for voters to just go with their guts? For most people, the gut is more reliable than the brain. That’s just a fact about the relative capacities with which most people are endowed.

Nichols theorizes that line-crossers are self-interested voters looking for better “deals”—but he doesn’t explain why this would be the case, or why it would be such a moral or systemic problem if it were true. If the political parties are so stable that coherence can only be found in sticking with one or the other, then why would the same person be able to get a better deal on one side than on the other? Why are those who change party affiliation—as Nichols did—necessarily any more self-interested than those who don’t change? Actually, there’s little reason to think a self-interested person would bother voting at all—the so-called “paradox of voting.” And Nichols attributes to these voters both a comfortable, prosperous lifestyle and a desire for “apocalypse”—how could that combination be self-interested? Nichols engages none of these debates.

The third chapter covers more familiar ground: There’s an epidemic of narcissism in America, along with rage, resentment, and nostalgia. Of course Nichols’ formless pomposity on this subject cannot match the keen rhetorical incisions of Christopher Lasch, whom he cites. What’s odd about this chapter, however, is that Nichols, now relaying passages from the famous 2005 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America by Thomas Frank, adopts the view that resentment causes Americans to vote against their self-interest. And no, you are not going crazy: Just a paragraph ago, I was explaining Nichols’ claim that the problem with American democracy is that voters act on pure self-interest.

The fourth chapter is meant to address critics of liberal democracy. Like many centrists, Nichols, somewhat accurately, diagnoses a “horseshoe” in these critiques: Left-wing and right-wing critics make the same sorts of complaints. But what’s that supposed to prove? He uses the term “illiberal” as a seeming synonym for anti-democratic. But, like many who claim to be in favor of or against the political philosophy of “liberalism,” he never really explains what it is, or what it would mean to fail to embody it. And isn’t this exactly the opposite of what Nichols said before—that the dissatisfied people don’t in fact agree with one another? Again, Nichols seems almost offended by the idea that lines might be redrawn, that coalitions might shift. Eventually, he comes to the conclusion that even well-intentioned critics of liberal democracy, who are “drawing our attention to real problems,” are hypochondriacs, and that “treating them as if their complaints are real can do more harm than good.” So much for the trust and reasoned discourse that Nichols thinks can solve our deliberative problems.

Nichols seems almost offended by the idea that lines might be redrawn, that coalitions might shift.

Nichols is defending something, but he doesn’t seem to know what he’s trying to defend. “Democracy is a set of behaviors and beliefs that make institutions work,” he offers. Let’s assume this idea is offered seriously. If democracy is really a set of behaviors and beliefs on the part of citizens, then even a monarchy could turn out to be democratic. Later, he writes: “No society can maintain a good democracy . . . if it must rely on a population of bad citizens.” Nichols seems to honestly think that only people who vote in “good” ways deserve to vote at all. He’s more anti-democratic than the anti-democratic sentiment he’s concerned about!

Is it fair to take any of this stuff seriously, or is it just mean? Nichols is a kind of virtuoso of the empty sentiment, the filler sentence. Usually this sort of sentence is a sign a writer is straining to meet a word count or a deadline, something that’s palpable in many of the books I review. But Nichols writes entire books of filler. “In a liberal democracy, citizens are masters of their fate.” “Civic introspection is an indispensable duty for voters in a democracy.” That Our Own Worst Enemy is bearable at all is mostly a consequence of Nichols’ awareness of his own vices: He writes that some of his solutions involve “moral scolding” which is “usually [his] core skill set.” Every time Nichols seemed to catch himself and say, “Uh oh, there I go again,” I felt a little bit less inclined to hate the book. Thankfully, he only did this a few times, leaving me free to provide an honest accounting.

An anti-terrorism “expert” from the Bush days who is now reinventing himself as an “expert” on anti-democratic movements in the aftermath of Trump, Nichols never really tells us what he means to defend, and he doesn’t tell us how the ideas he shares are meant to count as a defense of whatever it is that he means to be defending. And it’s a shame, because the core questions Nichols broaches about the characteristics citizens require for a democracy to function, the popularity of critiques of liberal democracy, and why apparent material progress seems to leave many people unsatisfied, are interesting and provocative ones—and way too important to be left to experts.

Oliver Traldi is a John and Daria Barry Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions in the Department of Politics at Princeton University.