Tortured Soul

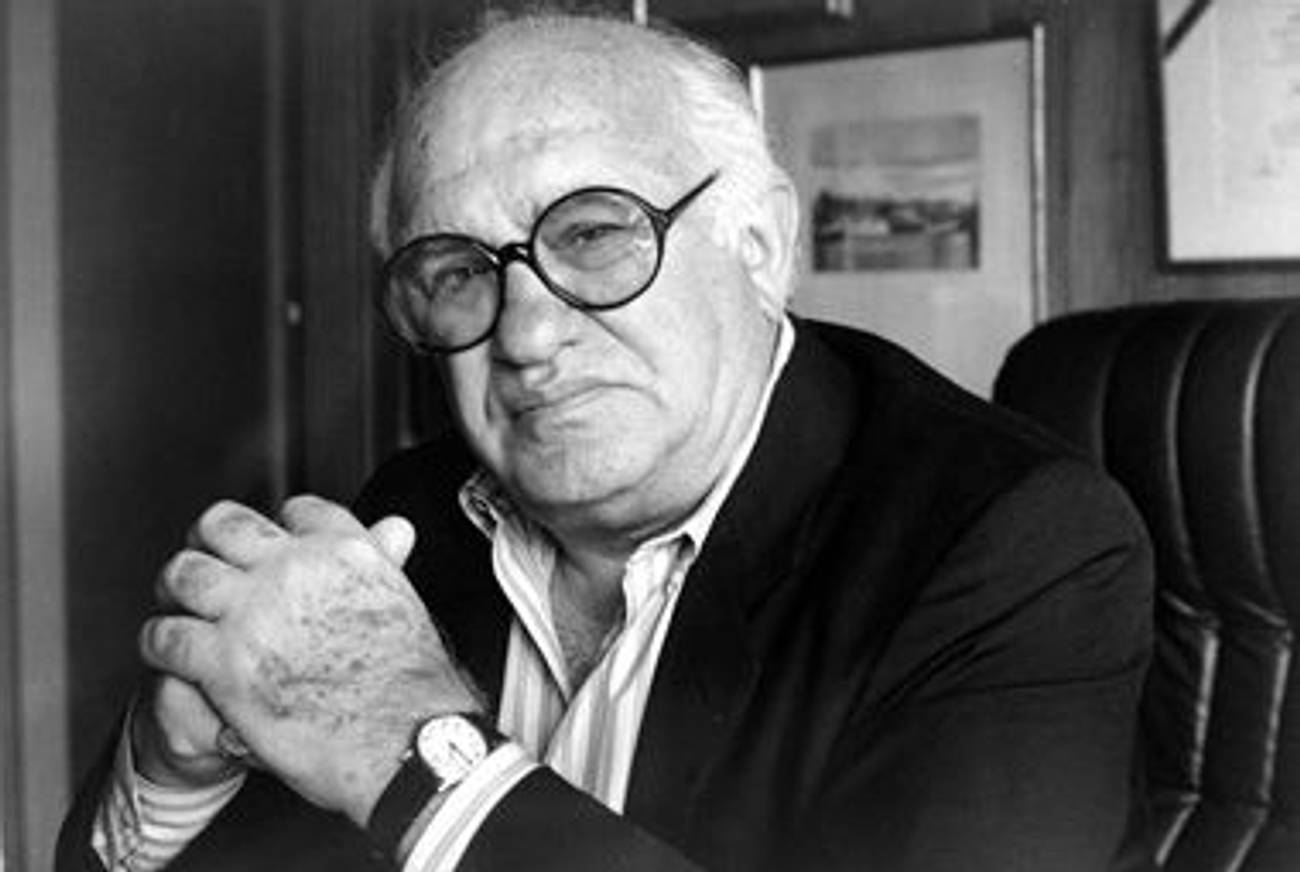

Thirty years ago, Buenos Aires newspaper publisher Jacobo Timerman emerged as a crusading human rights icon. Newly declassified documents offer a fresh—and more complicated—view of the Argentine dissident.

This is the first in a two-part series.

In a now-declassified document titled “Conversation with Jacobo Timerman,” Robert C. Hill, the U.S. ambassador to Argentina from 1974 to 1977, wrote to his superiors in the State Department about a lunch he had with the influential Argentine publisher in September 1976, six months after the military coup that toppled the government of Isabel Peron. Timerman, the owner of the daily newspaper La Opinión who later became a well-known symbol of resistance to Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship and a human rights advocate, was often consulted by the ambassador about political developments in the country and about the situation of its Jewish community. Hill’s memo consists of four points. The first two, on the country’s politics, are brief; the second two, on its anti-Semitism, are longer:

On Sept. 20 I lunched with the owner of La Opinion, Jacobo Timerman. Surprisingly, when I raised the question of anti-Semitism in Argentina, Timerman replied that there was no such problem here, and that concern over this largely imaginary problem results from the overraction [sic] of Jewish organizations in the United States. He went on to say that he thought indeed this accounted for a good deal of the international concern over the question of Human Rights in Argentina. If, he said, it could once be demonstrated that there was no problem of anti-Semitism in Argentina, we would see a simultaneous cooling abroad in other human rights problems since Jewish organizations would then lose interest.

Hill is baffled by Timerman’s attempt “to explain away anti-Semitism in Argentina.” He writes: “Possibly the problem has been somewhat overblown by some organizations that are quite naturally concerned. To suggest that it really is no problem, however, simply flies in the face of history and of the concrete facts…. The machine-gunning of Jewish stores and the bombing of the synagogue and Jewish civic centers may not indicate the beginning of a pogrom, but they certainly do indicate that there is a problem.”

November 2009 marked the 10th anniversary of Timerman’s death. Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number, his 1981 memoir of being arrested, tortured, put under house arrest, stripped of his Argentine citizenship, and exiled to Israel by the Argentine military junta because he was a Jew. El caso Timerman, the Timerman case, became a symbol of Argentine human rights abuses in the late ’70s and early ’80s and a grim reminder to Jews around the world that they are never safe. His story can be seen as a heartbreaking tale of failed assimilation, of a Jewish immigrant who aspires to and achieves acceptance in a gentile nation that eventually turns on him. That was the story that I believed when I read his testimony as a graduate student in the late ’80s. But as I began researching this complex man and his legacy, an even more unsettling narrative revealed itself, with broad implications for a moment in which anti-Semitic violence has reached levels not seen since the end of World War II and in which some Jewish communal leaders and intellectuals have responded by publicly distancing themselves from Israel and the organized Jewish community for reasons that are often phrased in the language of human rights, personal conscience, or national interest.

Though the U.S. ambassador and Jewish communities in the United States were persistent in their investigation of the existence, level, and depth of Argentine anti-Semitism, Timerman in his many consultations with U.S. officials played an active yet subtle game that did not provide any clear answers to what in retrospect seems a simple question. When the State Department compared the Argentine junta to the Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Timerman’s newspaper ran an article staunchly defending the junta. The piece argued that unlike the Pinochet dictatorship, which lacked noble goals, Argentina’s junta aimed for “the reimplantation of an authentically representative, republic[an], and federalist democracy in Argentina.”

January 26, 1977, marked the beginning of a change in Timerman’s position. Suspecting that his arrest was imminent as he spoke again with Ambassador Hill, he did not retract his claim that there was no anti-Semitism in Argentina. Yet he admitted that some members of the military were strongly anti-Semitic, especially those hardliners who had been heavily influenced by the Germans during World War II. Timerman ended by saying that the current situation in the military was fragmented because Gen. Jorge Videla, whom he considered a moderate, lacked the power to control other generals. “It is entirely possible,” he said, “that none of the military sense the strong international, and particularly American, reaction against what are seen as anti-Semitic incidents in Argentina.”

This account echoed Timerman’s statements from September 1976, in which he had told Hill that if the Americans would just stop overreacting, stop being so loud and concerned about anti-Semitism, the issue would disappear. Timerman’s position was in line with the public stance of Jewish communal organizations like the Delegation of Argentine-Israeli Association. In June 1977, several months after Timerman’s arrest, the president of DAIA, Nehemias Resnizky, whose own son would later be kidnapped, told the Argentine Jewish community that though Argentina was not an anti-Semitic country nor was there any official anti-Semitism, there were “powerful economic groups who always make the ritual offerings of the Jewish minorities as a scapegoat” for other national problems.

On March 31, 1977, 15 days before his arrest, Timerman, together with his son, Héctor, and Mario Diament, the managing editor of La Opinión, met with Michael O’Brien, press officer of the United States Information Service. At the meeting, Timerman passed along his thanks to President Carter for his strong human rights stance, but asked that the U.S. not punish Argentina for its poor human rights record, as that would lessen its ability to transition to democracy. Timerman then told O’Brien that he knew the government was “preparing to denounce him as a communist and a ‘voice of subversion’” and that it would be taking some “drastic action” toward him in the following months. He wryly concluded, in O’Brien’s account, that if “he were to be killed by leftists it would merit only a small story in [the] U.S. press. But if right-wing para-military did him in, it would be front page news for weeks.” Neither happened. Instead, Timerman was arrested in the early morning hours of April 15, 1977, and Hill sent a cable the same day:

Jacobo Timerman and Enrique Jara, publisher and chief editor respectively of “La Opinion”, were taken from their homes by an armed group of individuals in civilian clothes in the early morning hours of April 15. The individuals reportedly identified themselves to family members as “officers,” but families believe this may be a phony lead. Timerman and Jara were instructed to take along with them cigarettes, food and clothing. There has been no statement from the government concerning this action, and we have no confirmation at this point as to who has them or where. There is a presumption among press sources, however, that the detention, if indeed they have been detained by govt forces, may be related to the ongoing investigation of the financial empire of David Graiver.

2. Further developments will follow.

Hill

Timerman expected his arrest and believed his incarceration would be short. When the junta arrested him they cited his alleged connections to David Graiver, an Argentine-Jewish financier accused of managing tens of millions of dollars of ransom money collected by the Montoneros, a Peronist left-wing guerrilla group. Timerman admitted that Graiver held a 45 percent share in La Opinión but denied any knowledge of money laundering for the Montoneros. Though he knew he would be linked to Graiver’s financial scandal, he was confident the charges would be cleared up quickly. When he was encouraged to leave the country, both by his son Héctor Timerman and by Mario Diament, he refused. In separate interviews, Timerman’s son and Diament told me they’d heard Timerman say he would never give the anti-Semitic hardliners in power the satisfaction of seeing a Jew run. Héctor Timerman, now Argentina’s ambassador in Washington, D.C., recently wrote an essay in which he described the conversation. He wrote that his father “didn’t want the anti-Semites in power to portray him as a cowardly Jew. He said he wanted to be like the heroic people of Masada, who chose to keep fighting and then to commit suicide rather than be captured.”

Though the military claimed to have arrested Timerman because of the Graiver scandal, U.S. Jewish organizations saw the Timerman case as a modern-day Dreyfus affair. In November 1977, the Anti-Defamation League published a report stating that Jews had been targeted by the junta at higher rates than other members of the population, that they were subjected to crueler methods of torture than non-Jews, and that they were frequently interrogated “about communal affairs and bizarre issues such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and alleged Jewish plans to create a second Zionist state in Argentina.” The ADL report went on to state that “the Timerman case has had a shattering effect upon the entire Jewish community. The Jewish masses have lost a champion and a voice. Under Timerman’s direction, La Opinión, one of Buenos Aires’s leading dailies, did battle with Argentine anti-Semitism and championed the cause of Zionism and Israel. Now, Timerman is silenced and humbled, and his paper is controlled and run by the army.”

In August 1977, four months after his arrest, Timerman was interviewed by U.S. Congressman Benjamin Gilman. Gilman described Timerman, who greeted him in casual clothes and a sports jacket, as subdued but mentally sharp. “In fact,” Gilman recalled, “Timerman demonstrated considerable acuity, and his conversation was at times laced with bittersweet irony.” Aside from discolored skin under one of his fingernails, Timerman did not show any sign of torture. He admitted to Gilman that his interrogators never asked him about Graiver but constantly taunted him because he was a Jew, a Zionist, or, worse still, in their minds, a Marxist. He also told Gilman that the majority of his interrogations concerned a presumed world Jewish conspiracy against Argentina. His interrogators told him that Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin was a Jew, asked him what he knew about secret meetings between Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and the Montoneros, and sought information about a secret plan of the Elders of Zion to take over Patagonia. Timerman told Gilman he supported President Jorge Videla, and he asked the congressman to pressure the United States to back the moderates in the military regime and not the hardliners. As Gilman got ready to leave, Timerman shook his head sadly and said, “Look what happens to a man who was trying to defend the government.”

***

Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number was written in Israel one year after Timerman was expelled from Argentina and stripped of his citizenship there. In the Spanish edition’s foreword, not included in the English translation, Timerman writes that he has arrived at his final home, Israel, after surviving the Inquisition in Spain, the Cossacks in Ukraine, the Nazis in Germany, and the junta in Argentina. “We have completed our voyage,” he writes of the Timerman family. Two years later he would lash out at his new homeland for invading Lebanon, and after three years he would leave Israel, never to return.

Born in Bar, Ukraine, the 5-year-old Jacobo Timerman arrived with his parents, Nathan and Eva, and his older brother, José, in Buenos Aires in 1928. Nine years earlier, in 1919, Buenos Aires had experienced a pogrom that resulted in 800 dead and 4,000 wounded. The attackers’ mantra would have been familiar to Ukranian Jews: Haga patria, mate un judío, which, roughly translated, means, “Be a patriot, kill a Jew.” The family settled in Buenos Aires’s only Jewish neighborhood, and Nathan became a traveling textile merchant. They lived in poverty during the Great Depression, which crippled Argentina’s agricultural exports. Despite their timing, they had high hopes for their future in Buenos Aires.

Timerman’s book contains a few striking memories that suggest the deep attachment and feelings of extreme vulnerability that the writer associated with his Jewish upbringing. He recalls when, as a 10-year-old boy, he asked his mother why so many hated the Jews. “Because they don’t understand,” his mother replied. Timerman writes, “yes, my mother in good faith believed that if the anti-Semites understood us, they’d stop hating us.” When Jacobo finished school he became a young bohemian Jewish intellectual; he wrote poetry and frequented literary groups, and he became heavily involved with Hashomer Hatzair, the socialist and Zionist Jewish youth group. His early youth was linked to Jewish organizations and the establishment of the state of Israel, for which he maintained unwavering support. Roberto Graetz, a rabbi who visited Timerman while the writer was in jail, told me when I met him in Argentina last summer that journalists at La Opinión were given free rein to write anything so long as it was not critical of Israel.

Though Prisoner contains a few graphic scenes of torture, they are not the subject of his book. “For the man who’s been tortured and has survived,” Timerman writes, “this is perhaps the least important topic.” What words, he asks, could possibly describe torture? Rather than focus on the details of his torture, Timerman wrote about its causes. He sees his Jewish identity for what it had always been, an egregious thing the junta preferred eliminated, “disappeared.” His torturers, he wrote, took special pleasure in the act, not because they hoped to obtain information on the Graiver case, the legal reason for his imprisonment, but simply because he was a Jew. While applying electric shock, they chanted with a kind of wild hysteria: “Jew… Jew…. Jew…Clipped prick…. clipped prick… Jew!”

***

In The Longest War, Timerman’s scathing critique of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, there is a conspicuous pause at the point at which he pays tribute to his father, who died unexpectedly, in 1935, when Timerman was 12 years old. “His grave is still open,” Timerman writes, “and my pain is endless. I don’t know what to do with him after so many years. Because my father was in love with his Judaism my pain is so Jewish, and because I carry inside me his Jewish grave, my heart has other open graves so that my father will not be alone. Inside of me I bear a Jewish graveyard.”

Timerman’s refusal to criticize Israel did not survive his adopted country’s decision to invade Lebanon. “For the first time,” he wrote, “Israel had attacked a neighboring country without being attacked; for the first time it had mounted a screen of provocation to justify a war. For the first time Israel brought destruction to entire cities: Tyre, Sidon, Damur, Beirut. For the first time military spokesmen had lied. For the first time the Israeli press joined them in their successful mission of lying to the public. For the first time officers and men did not know the objectives or the goals of the campaign. For the first time the actual damage inflicted on the invaded country was hidden along with the number of deaths. For the first time reservists on leave from the front demonstrated on the streets of Jerusalem because they consider themselves betrayed.”

Timerman was incensed with Israel for acting as an oppressor, not only because the wounds of his torture in his former homeland were still fresh, but because to him Israel had the unique (if unfair and impossible) duty of being a light unto the nations. “I’m angry … with us, with the Israelis, who by exploiting, oppressing, and victimizing the Palestinians have made the Jewish people lose their moral tradition, their proper place in history.”

In some sense, his treatment of Israel and the Israelis was no different than his treatment of any other object of affection or interest in his life. His childhood friend, Abrasha Rotenberg, who would later become a key financier of La Opinión, stated bluntly in an interview in 2000 that Jacobo Timerman, aside from being a man of contradictions, was a man who didn’t care even for success; his enjoyment of his own achievements was short-lived; he would grow easily bored; he would move on. Timerman, Rotenberg said, liked to create scenes in which he became the protagonist, and then he liked to tear them down.

By the time he founded La Opinión, Timerman had lived through several military coups and changes in government and he had intimate connections with almost every regime. A telling example of his strong desire to be part of Argentina’s elite was his awkward friendship with Ricardo Güiraldes’s nephew, Juan José Güiraldes. Ricardo Güiraldes wrote the famous gaucho novel Don Segundo Sombra, and his family represented the wealthy landowners of the pampas of Argentina. Güiraldes and his family were emblems of Argentine nationalism. His nephew, an Air Force brigadier, would confess to journalist Graciela Mochovsky that if he were to write a book on Timerman it would be titled Timerman the Jew. When during the interview Mochovsky asked him about anti-Semitism, Güiraldes stated that it was simply part of the Argentine national code. To value Western and Christian ideals meant to reject Judaism and Jews, and to hold suspect anyone who had or was part of communist or socialist parties or organizations.

Having Güiraldes on his side, working with him on journalistic ventures such as the newsweekly Confirmado granted Timerman full acceptance in the Argentine elite; his adopted homeland came to view him as one of its own. In fact, however, Timerman didn’t become an Argentine citizen until the 1960s. His early communist ties and immigrant status as a ruso—which means “Russian” but is also a pejorative term to designate someone an outsider—prevented him from attaining it earlier. In the end, his citizenship lasted less than 20 years.

Between his arrival as a child in Buenos Aires in 1928 and the return of Argentinean democracy in 1983, Timerman lived through the rise and fall of some two dozen presidents and military dictators. The 1976 military overthrow of Isabel Peron, Juan Peron’s third wife, brought in the most brutal dictatorship that Argentina had ever known. Its campaign of repression and terror was dubbed the “Dirty War” by the junta itself.

In its first communiqué to the country, on March 24, 1976, the junta warned the citizens that Argentina was now under military control. It suspended political parties, revoked the right to strike, imposed a curfew, instituted a death penalty, arrested officials of previous political parties involved in affairs deemed harmful to the country, dissolved the national congress, and dismantled the Supreme Court. Videla was named president, and each branch of the military—the Army, Navy, and Air Force—controlled one third of the government. Hardliners in the military described Argentine society as mortally ill and in need of the doctors of the junta to heal it. Soon the junta initiated a Proceso de la Reconstrucción Nacional—process of national reconstruction—which aimed to cleanse the nation of subversives who threatened the values of the homeland.

During the six-year Dirty War, the junta killed an estimated 30,000 people. Officially, most are not dead but missing; each is known by the noun created from the verb to disappear: un desaparecido, a disappeared. Though his newspaper initially praised the military and justified the coup, this did not grant Timerman security. He was categorized as a subversive and subject, like thousands of others, to the proceso, the social cleansing. He was arrested on April 14, 1977, and unlike other high profile prisoners, he was not released until almost a year later. His colleague at La Opinión, Enrique Jara, was released within days and absolved of any crime. Other journalists were also released quickly. Timerman was caught between competing generals of the army, navy, and air force, who used the fact of his Jewishness either to garner power or to criticize their opponents within the junta.

How could this powerful man find himself in a torture chamber while his captors chanted judio de mierda, judio de mierda—shitty Jew? Like the German Jews before the Holocaust, Timerman firmly believed that he was part of Argentine society, that he was fully assimilated, an Argentinian. But like his predecessors, he was tortured as a Jew. “The fact is that once he was made to disappear, he suffered as most Jews that disappeared did,” Graetz told me. “Jews received a double dose.”

Though el caso Timerman can be read as an example of how Jews are never safe outside Israel, that is not the lesson to be drawn from the life of Jacobo Timerman. The myth of Jacobo Timerman was largely created by us, the members of the Jewish Diaspora, the human rights organizations of the ’80s, the Jewish organizations in the United States who wanted to believe Timerman’s story and to ignore his life before he “was disappeared.” Timerman was such an apologist for Argentina’s brutal Junta that he at first denied its anti-Semitism, only to claim—after torture and exile—that he did not hide from his impending arrest because he did not want to give the military the satisfaction of seeing a Jew run.

Bridget Kevane is a professor of Latin American studies at Montana State University.

Bridget Kevane is a professor of Latin American and Latino literature at Montana State University in Bozeman. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, ZEEK, the Forward, and Brain, Child, among other publications.

Bridget Kevane is a professor of Latin American and Latino literature at Montana State University in Bozeman. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, ZEEK, the Forward, and Brain, Child, among other publications.