Jews Drinking Coffee and Watching the Republican Convention

Rolling commentary on the Republican National Convention, as it happens

Instead of presenting you with the hard-hitting and in-person team coverage of the Democratic and Republican conventions that we planned back in January (a big shout-out here to Tablet’s Airbnb hosts in Milwaukee and Charlotte, who gave us our money back), we will proudly be sharing our remote impressions of this year’s Democratic and Republican Party-branded Zoom calls—which for all we really know are Deep Fakes produced by Kremlin agents or by a high school kid in Tampa, Florida.

It’s August, and our brains are fried by six months of anxiety about the pandemic and the prospect of ever-wider social collapse, and by watching baseball games with no people in the stands, and ballooning credit card debt, and the knowledge that we are all wholly owned subsidiaries of Google and Amazon. None of us wants to begin thinking about what happens after Labor Day, when schools will attempt to reopen and flu season starts.

So why not enjoy the rest of our social distanced summer at a national park or drinking vodka with Xanax? Well, because no matter which party you believe poses the most immediate danger to America, this year’s election seems likely to have a profound effect on the future of the country that most of us are stuck living in even after the Canadian border reopens. It therefore goes without saying that the 45% or more of our fellow citizens who will vote for the wrong party in November are corrupted traitors who should be canceled, banned, and hopefully fired from their jobs, if they are lucky enough to still have them, before being sent to reeducation camps. That’s what it means to be an American.

Take it away, gang. —The Editors

• 2020 Is Not 1968 by Jonah Raskin

• The Boaters by Armin Rosen

• Horror and Demagogy by Paul Berman

• The Custodial Conventions by Sean Cooper

• The Loomer Conundrum by Jacob Siegel

• The Double-Edged Sword of Unrest by Wesley Yang

• Gatsby Meets Trump: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Prescience by Jonah Raskin

• Life in the Bubble by Armin Rosen

• The Rabbi by Paul Berman

• The Internet Presidency by Sean Cooper

• What We Have Learned From the Party Conventions by Michael Lind

• Is Biden Blowing It? by Noah Pollak

• I Can’t Stop This Feeling by Liel Leibovitz

• Melania’s Big Night by Jonah Raskin

• Don’t Cancel Bette Just Yet by Jacob Siegel

• My Conversation with a Real California Republican by Jonah Raskin

• The Discordant Convention by Paul Berman

• The Shock Factor by Armin Rosen

• Misleading on the Opioid Crisis by Sean Cooper

• The American Spirit on Display by Tony Badran

• The Empty Chair Election by Yair Rosenberg

• Civilization and the Republicans vs. Chaos and the Democrats by Jonah Raskin

• Versions of Reality by Paul Berman

• The Normie Election by Armin Rosen

• The Self-Sabotage of Low Expectations by Noam Blum

• The Forgotten People by Sean Cooper

• Tim Scott’s Case for Trump, Sans Trump by Wesley Yang

• Media and the Presidency: A Look Back by Jonah Raskin

• Ruminations on the Cusp of the RNC by Jonah Raskin

• Obama to the Rescue by Lee Smith

• What to Do About Trump? The Same Thing My Grandfather Did in 1930s Vienna. by Liel Leibovitz

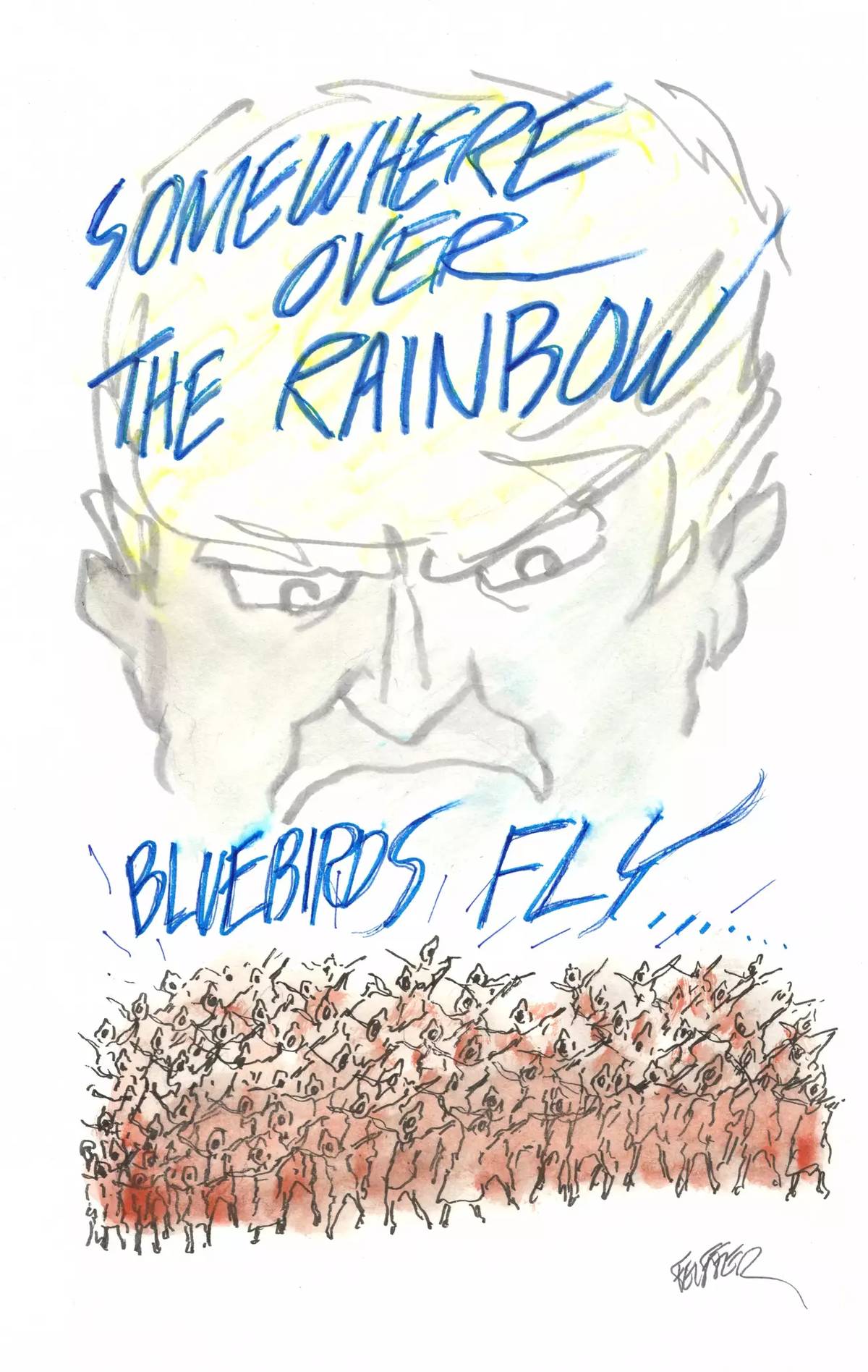

• Trump and the Joys of Hatred by Paul Berman

By Jonah Raskin

2020 is not 1968, contrary to what I’ve been told over and over again. I am no longer 26 years old. I know no one now as I did then who is dying in the jungles of Vietnam. Donald Trump is not Richard Nixon, the Republican Party of today is not the Republican Party of then, nor is the Democratic Party of today the Democratic Party of that era. Chicago is not the same city it was in ‘68 when the police rioted and cracked the skulls of reporters. History does not occur twice, as Karl Marx insisted, and it’s not deja vu all over again, as Yogi Berra noted. Joe Biden isn’t Hubert Humphrey and Kamala Harris isn’t Ed Muskie, Humphrey’s running mate. Antifa is not the Weathermen, Black Lives Matter is not the NAACP of ‘68, and members of #MeToo are not the same as the feminists who protested at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City in ‘68.

Yes, there are links between then and now, and echoes of the past in the present, but we’re living in a new era with smartphones and laptops, Netflix, Amazon, Google, Facebook, plus all kinds of goods from China. Russia has emerged from the shadows of the USSR and Beijing has a revitalized Communist Party that runs a capitalist economy. There ain’t no socialists left in Europe today as there was then. The terrorists of the Middle East are not the same as the guerrillas of Latin America. Fidel Castro is dead and so is Yasser Arafat. Benjamin Netanyahu is not Levi Eshkol. COVID-19 is not the flu of ‘68, and the Lakers of today aren’t the Lakers of then who lost to the Celtics in the NBA Finals in ‘69. In the present moment, which can feel chaotic, it’s understandable that people want to grasp hold of life preservers, rafts, and even straws, but easy comparisons between 2020 and 1968 won’t help. Global climate change ain’t the same as the fluctuating weather patterns of the past. It’s hotter now than ever before on Earth. I’m no longer a New Yorker, but a Californian living in the midst of unprecedented lightning strikes and devastating fires. It’s the end of the beginning and the beginning of the end. I get dressed every morning, put on my pants, make coffee, sit down at my desk and write on my Mac. Welcome to 2020!

By Armin Rosen

I write from the surreal paradise of Block Island, where a flotilla of right-wing watercraft greet the arriving visitor, at least a half-dozen Blue Lives Matter, Trump for President, and Gadsden flags fluttering over the gently bobbing pleasure vessels moored in the village port. For many weekend watermen, simply owning a boat is an insufficient expression of one’s Boater-American identity, newly self-aware during the era of Donald Trump.

Even during a breather in liberal New England one can’t avoid reminders of the larger American breakdown, a syndrome by which the members of such a whimsical population subcategory as Boater must declare their Boater-ness, and in which that declaration is tied to a particular candidate, a particular program, maybe even a particular vision of the what this country even is. The boats and banners vanish at Mansion Beach a mile up the road, a ribbon of sand below high dunes, with silent, gray wooden houses transposed from an Andrew Wyeth painting looming over the near ridgeline. I always say that there’s no feeling on earth better than the shock of cold saltwater on a northeastern beach. How much of this revivifying substance will I yearn to pour over myself on Nov. 3, and why?

The Trump boats now seem to tell the story of this entire convention and maybe this election as well. This week was certainly more entertaining than the DNC—mission accomplished on that front. The current incarnation of the GOP gave its version of things about as well as it could have. Trump’s speech was somehow even more grandiose than his vaguely Castroesque convention performance in 2016, and he capped it off with enough fireworks over the National Mall to summon forth memories of the Brits torching the place in 1814. Whatever. The marketing might not matter much in the end: Millions of people are going to choose their president based on immutable inner urges, which are increasingly tied to pseudomystical feelings of group belonging, many of which would not have made much sense to us in pre-Trumpian times. It is to our misfortune that they make so much sense to us now.

This has been an unusually stable election season, with just about every poll showing Biden on the way to a large victory. There’s little reason to disbelieve that that’s where we’re heading. But there’s reason to doubt that the outcome will bring any sense of closure. Something tells me those Trump flags will still be up Nov. 4. The Boaters aren’t going anywhere.

By Paul Berman

To listen to the president last night, and to his most vivid endorsers, Rudy Giuliani and the president of the New York Police Benevolent Association, Patrick Lynch, the dreadful threat facing America right now consists of outbreaks of looting and arson here and there, and a spike in violent crime in New York—all of which was presented as the hidden program of a Democratic Party. And, to be sure, looting and arson and violent crime are terrible things.

But what is wrong with these people? The coronavirus death toll by now is inching its way toward 200,000. Some parts of the country have not yet undergone the moments of terror. But New York City, which was a focus of last night’s orations, has experienced a degree of horror that rivals or outrivals the horrors of 9/11. It is not because violent crime has gone into an uptick in a number of precincts in Brooklyn and the Bronx. It is because of mass death. It is because of the months of screaming ambulances racing down the avenues, and the horrors at the hospitals and the morgues.

Trump devoted a portion of his speech to extolling the brilliance of his response to the pandemic, and how brilliantly the economy is beginning to recover—and those portions of the speech were still more grotesque. Endless thousands of people are dead because of the incompetence of his response, compared to the response of other governments around the world. And the economy, with many millions of people out of work? And the future that awaits us in these next months, with the pandemic still out of control? And the schools uncertain what to do? And the terrified parents? And the college students?

The reality of Trump’s response to the pandemic was visible in the White House scene itself, with a crowd of people clumped together, maskless, in the very behavior that doctors and epidemiologists have stressed to us must be avoided. Go ahead, get yourself infected, was President Trump’s message to the American people.

The spectacle was revolting even in its minor aspects. Custom and the Hatch Act ought normally to forbid the use of the White House for a purely political event. The president decided to put the White House to use, anyway—which, in this instance, does not seem a terrible thing to do. But the decision is expressive of Trump’s approach to politics and the presidency as a whole. It is a decision to be unprincipled—a decision to put everything to his own use, regardless of law and democratic tradition.

This is what we have seen in his collusions with the Russians, as documented just now by the Senate Intelligence Committee (even if the committee has delicately preferred the word “cooperation” to describe the collusion of Paul Manafort with a Russian intelligence officer). How terrible those collusions look today!—terrible because they contributed to bringing an incompetent demagogue of uncertain loyalties to the White House! The same spirit of subverting the American interest to Trump’s personal interest governed his attempt to coerce the government of Ukraine. And the same spirit has governed his catastrophic manipulations of the scientific experts and their recommendations.

The present instance—the use of the White House for an overtly political purpose—shows that, even now, he insists on his own narrow purposes. At the Democratic convention, one speaker after another spoke of Trump as a danger to the democratic culture. The speakers were right to do so, and the danger was visible even last night, if only in a small and representative way.

Let other writers go on about the normal categories of American politics—the shifting of one sector of the population or another to the Republicans or to the Democrats, the play of politics in the battleground states, the foolishness or wisdom of the political advisers. The main story is what was visible last night. It is the demagogy of a president who wishes to convince us that we are not undergoing the horrors that we are undergoing. And it is the demagogy of a president who regards with contempt the democratic grandeur of his own country.

By Sean Cooper

Of the however many dozens of speakers that came before us over the past two weeks, the keynote addressees and bootlickers alike, there were a few shared traits, but the primary one, I suspect, which we’ll realize in due time, is that these respective cohorts aren’t around to last. For the Democrats and Republicans both, they strike me now as custodians, caretakers of their respective political vessels awaiting the next leader to come take over the helm.

Vice President Joe Biden has already signaled he’d be a one-term president should he win the election, marking his time in office a transitionary one before he even takes over the White House. For President Trump, he has spent much effort assuring his base that his promises have been kept and no one has been forgotten. Surely this mantra will continue, which is nothing short of a recipe for disaster, as soon as enough of his most ardent supporters begin to break off, realizing that promises have been broken and they are among the many with good reason to feel betrayed and left behind. Particularly across the reddest states, where job opportunities continue to decline and drug overdoses remain at some of the highest rates nationwide.

What comes after a Biden transitionary presidency remains unclear. The left is in phenomenal disarray, too many chefs all trying to make a meal in a small kitchen. For Trump and his base, it’s difficult to see a future that doesn’t cultivate more animosity and more strife, both against those he perceives as its enemies here and abroad. That kind of resentment is a powerful tool, and can be leveraged to bring about massive change across American life. To whomever takes over the party after Trump, it seems as though this moment at least was entirely a transition, when the right was watched over but never truly led, a moment that will in hindsight be revealed to be a prelude to what will come next.

By Jacob Siegel

A few days before the start of the Republican National Convention, President Trump and Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz, who also spoke at the convention, publicly congratulated the young, right-wing political creature Laura Loomer for winning her primary race in a Florida congressional district. Loomer’s great contribution to the Republican Party is the force of her obvious personality disorders, an internal motor she has used to propel herself back into the spotlight in the aftermath of her many public political stunts. Her views are bigoted and demented but never in interesting or novel ways. In all, Loomer is a minor figure and will remain one even if she wins a seat in Congress. Yet President Trump congratulated her from his Twitter account, as did his fellow convention speaker Gaetz.

Why would Trump publicly support someone like Loomer except to stick it in the eye of liberals and the notions of decency toward which they occasionally gesture? The president gains nothing from Loomer. He already has the anti-Muslim kook vote locked down. Loomer may represent a small part of the voting base but she has an outsize significance as a symbol of state-sanctioned counterradicalism. How different the Loomer endorsement was from the convention itself, which repeatedly and prominently featured women and nonwhite speakers, a move that would be truly unusual for a white supremacist party, though not for a nationalist-populist party.

All I could think of on the last night of the Republican convention was the violence and rioting and deaths in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Three people were shot Tuesday night, two of them killed, by a 17-year-old, Kyle Rittenhouse, who traveled to the city to act as a lawman and general do-gooder. He walked the streets presenting himself for interviews and documentary footage before the livestreaming cameras with a rifle and medical kit slung crosswise on his underdeveloped frame, ready to prevent looting and render first aid.

The police were not out in force in Kenosha and so the streets belonged to whoever claimed them. Ownership reverted to the young multi-hued and sporadically armed demonstrators and insurrectionaries protesting the police shooting of Jacob Blake and the general injustice of society, and the far smaller group of young, mostly white, and uniformly armed militiamen belonging to organizations like the Kenosha Guard or the Boogaloos or to no organization at all. The militiamen like 17-year-old Rittenhouse were not exactly counterdemonstrators so much as they were attempting to be the law in those places from which the law had retreated or been strategically withdrawn by local government. Of course Rittenhouse had no right to be on those streets but neither did the people lighting fires and attacking elderly business owners.

Rittenhouse has been charged with murder and prominent Democrats have labeled him a white nationalist and white supremacist. There is, as yet, no evidence this is true, except that he appears to be a Trump supporter and police enthusiast. Rittenhouse, by all appearances, is not half the wacko that congressional candidate Laura Loomer is. The young man belongs to a classic American archetype: a nerdy police groupie with an amateur kit, not enough training, and a half-formed sense of his own heroic destiny. An out of work young man in search of a useful social function that he apparently could not find closer to home and in less dramatic, less livestreamed circumstances, and who was energized by the madness around him—a similar profile likely would fit many of the demonstrators in Kenosha.

By Wesley Yang

The Republican National Convention has one more chance to enact messaging with the power to secure it the presidency and realign the party for a generation. Such messaging would flow naturally from both the course of events and the standard package of Reaganite values to which it has defaulted throughout the convention. This would of course be a montage of destroyed storefronts accompanied by the plangent voices of Black and non-Black immigrant shopkeepers describing their abandonment by local authorities to looters and arsonists, young white radicals who have sought and found in insurrectionary violence a venue to launder thwarted entitlement into virtue. This montage would then be juxtaposed against the promises of the left-wing activists that have captured city governments in Minneapolis and Seattle to defund the police, and chyrons by partisan-aligned media declaring the protests “mostly peaceful” superimposed atop streetscapes wreathed in flame.

The messaging would of course be an opportunistic and cynical appropriation of the suffering of those Donald Trump used to capture the presidency by stigmatizing with a range of ugly epithets and promising to keep out of the country. But opportunistic and cynical appropriation has a way of working both ways. America is mostly a “land of opportunity” of the sort eulogized by the standard Republican talking points for its newcomers. The sudden recrudescence of street disorder and its opportunistic appropriation by partisan and corporate elites have placed media in the awkward position of serving as apologists for “fighting white supremacy” by smashing the windows and looting the livelihoods of Haitian, Mexican, and Vietnamese small-business entrepreneurs—recapitulating odious sophistry denying that “property destruction is violence” straight from the mouths of the Weather Underground, while trampling the lives of nonwhite newcomers to the country.

The sudden salience of the all-too-real consequences of this bizarre ideological freakout presents an opportunity to align the Trumpist coalition of white resentment with the immigrants who are the only people that still really believe in the American dream, in common cause against the hyperprogressive enemy. A party so committed to excluding immigrants that it fails to see the political opportunity in hypocrisy (and the attendant real compromises with what has always been a natural constituency such hypocrisy would eventually entail) is headed for the ash heap of history.

By Jonah Raskin

F. Scott Fitzgerald understood as well as Theodore Dreiser, the crusading author of The Financier, The Titan, and An American Tragedy, what motivated “the great American capitalists,” as he called them. Fitzgerald conjured a cast of fictional capitalists in his novel The Great Gatsby, a love story, a meditation on the American dream, and a saga about the environmental degradation of a continent. In chapter 2, the narrator, Nick Carraway, describes a “waste land” where the highway meets the railroad and where “ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys.”

Published in 1925 in the thick of the Jazz Age, Gatsby seems as timely now as when it first appeared in print when the nation hurled toward “the crack-up,” to borrow a phrase Fitzgerald popularized in 1936, four years before his death in Hollywood at the age of 44. Fitzgerald’s own story seemed to mirror the story of America itself, from the Roaring ’20s to the Great Depression.

If they could walk off the pages of the novel, the characters in The Great Gatsby would have attended the 2020 Republican convention and lined up on the side of Donald Trump. That’s especially true of suburbanite Tom Buchanan, who has a wife, a mistress, and a “cruel” body that’s “capable of enormous leverage.” Soon after readers meet him, he announces that “Civilization’s going to pieces.” The civilization he has in mind is pure white.

Buchanan touts a book called The Rise of the Colored Empires. Fitzgerald borrowed and tweaked the title from Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color, a popular work that influenced President Warren Harding. “The race problem here in the United States,” Harding told a crowd of whites in Alabama in 1921, “is only a phase of a race issue that the whole world confronts.” Meanwhile, millions joined the KKK and white violence against Blacks spread across the South.

Apocalypse now echoes apocalypse then. What goes around comes around. Harding’s, Stoddard’s, and Tom Buchanan’s views are amplified by whites today who feel that their own lives are threatened at home and around the world by people of color.

In Gatsby, Carraway explains that Tom and his wife Daisy “were careless people.” He adds, “they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.” In 1920, they would have voted for Warren G. Harding and in 1924 for Calvin Coolidge.

Fitzgerald was no flaming radical in the manner of contemporaries like Ernest Hemingway, who supported the anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War. But he was more critical of capitalism and the elite than his biographers usually allow. Before he sat down to write The Great Gatsby on Long Island in the mid-1920s, he confessed that he had allowed himself to be “dominated by ‘authorities’ for too long.” He added that “men of thought” like Rousseau, Marx, and Tolstoy, were more influential than men like Teddy Roosevelt and John D. Rockefeller, who “strut” about and mouth empty phrases about “100% American which means 99% village idiot.”

Fitzgerald’s strength as a novelist lay in his ability to steer clear of polemical fiction, even while he offered poetic and prophetic perspectives about American society and America itself.

“The whole burden” of The Great Gatsby, he explained in 1924, was “the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world so that you don’t care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory.” In his brilliant novel about lost dreams and powerful illusions, Fitzgerald performed a balancing act in which he plumped the forces of darkness, but didn’t allow himself to wallow in cynicism and despair. We might borrow his philosophy, and revive Gatsby’s own sense of “wonder” about life itself.

In The Great Gatsby, many of the crucial scenes take place off-stage. So, too, many of the pivotal events during the week of Aug. 24-27 happened, not at the Republican convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, but in the streets of Kenosha, Wisconsin, where a white police officer shot a Black man in the back, citizens rioted, and a white 17-year-old Trump supporter armed with a rifle was arrested and charged with intentional homicide in the deaths of two people and injuries to a third.

Fitzgerald, who was born and raised 350 miles away in white Saint Paul, Minnesota, would want Americans to think about violence and those who are culpable and guilty of perpetuating it, whether they’re Blacks or whites, cops or protesters who set fires and loot, and who, according to Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, brought “lawlessness” to the city’s streets.

By Armin Rosen

For the past few months the National Basketball Association has served as one of my barometers for the nation’s health. On March 11, the league suspended its season when several Oklahoma City players tested positive for the coronavirus. In the depths of April and May, the league formulated an ingenious plan to resume competition, and then executed that plan against almost impossible odds. The NBA playoff bubble at Disney World—which has not had a single positive coronavirus test despite being located in Florida—proved that Americans still possessed some agency against the forces of pestilence and chaos. It was a grand cooperative vision, so awesome an affirmation of hope and life in general that one was tempted to ignore how fragile the whole enterprise really was. COVID was not the only threat to this utopian vision of sports triumphing over the darkness. The NBA restart’s conspicuous social justice pageantry—the slogans on the backs of jerseys, the enormous Coaches for Racial Justice buttons, the league-sponsored PSAs that ran during every commercial break—hinted at a newfound sense of responsibility along with a deeper, barely hidden rift. One gradually suspected that the athletes, the vast majority of whom are Black, were wondering what they were even doing in Orlando, stuck playing basketball in a luxury resort they weren’t allowed to leave while America’s racial wounds were freshly inflamed. Maybe they were wondering what the moment demanded of them and still hadn’t found an answer.

Players of all races and backgrounds found one on Wednesday afternoon, when the Milwaukee Bucks called a wildcat strike before their playoff game against the Orlando Magic. It didn’t matter that it was the Kenosha Police and not the NBA that bore direct responsibility for the shooting of Jacob Blake: The moment demanded that the game not occur. Soon the day’s entire slate of contests was wiped out, an unprecedented act of mass protest in American sports and a historic event unto itself. By the end of the night, reports from a leaguewide, players’ only meeting suggested that the LA Clipper and LA Lakers—the latter of which counts the demigod and shadow league commissioner LeBron James among its players—were in favor of canceling the rest of the season. For the time being, whatever compact held the NBA together over the past four weeks of competition had fallen apart. Because I’ve now convinced myself the NBA is a microcosm of national fortunes, I can’t say the development came as much of a shock. Maybe it was predictable that it wouldn’t last—so little seems to last around here these days. But ESPN’s Adrian Wojnarowski has now reported that the players have decided to resume competition, temporarily resolving this latest episode in the country’s highest-profile standoff between labor and management.

Perhaps there is something or someone who can repair the national breach. That something is not the Republican Party, which celebrated law enforcement and the military on the third night of its convention—Mike Pence even spoke in front of a live audience at Fort McHenry. There were surprises, some of them weirdly relevant to the NBA tsuris: The blind Chinese dissident lawyer Chen Guangcheng, who dramatically escaped from China through Beijing’s U.S. Embassy in 2005, shuffled his hands as he read off of a Braille speech. Now there was a true hero of humankind, someone willing to exchange the entire rest of his life for the values America is supposed to epitomize and defend. And here he is throwing his support behind Trump, who has a somewhat mercenary relationship with those values—does that decision say more about Chen, or about the sitting president?

My mind already on the NBA, I couldn’t help but contrast Chen’s life of heroism with the league’s supine attitude toward the same Chinese regime that had persecuted him—until recently the NBA had a training facility in Xinjiang, home to China’s oppressed Uighur minority, an outrage that not a single player stepped forward to oppose. Last year many of the league’s stars, including James, lined up to defend the NBA’s apparent policy of suppressing its employees’ views on the mainland’s takeover of Hong Kong, which was apparently necessary for protecting the league and its players’ access to the lucrative Chinese market. There are rifts within rifts at this anxious moment in American life, and this entire election season poses a grim possibility: What if Americans don’t care whether they’re healed or not, or simply don’t want them to be healed at all?

By Paul Berman

Rabbi Aryeh Spero delivered the benediction last night, and it was awful. The benediction ought, in principle, to have beamed a soft light of religious reflection over the events, for the benefit of anyone hoping for such a thing. And the rabbi ought, in principle, to have given witness, merely by participating, to an American tradition of religious tolerance.

His big point, instead, was to invoke the MAGA slogan and drape it over the grandeurs of the American founding—which is to say, he gave his rabbinical blessing to Trump’s slogan. And he seemed to imply that the Democratic Party is challenging the essence of the American idea. In this fashion, the vinegar of political sloganeering mingled with what should have been the sweetness of the sacred; and the milk was curdled.

But the worst of it was his invocation of the “Judeo-Christian tradition.” The Judeo-Christian tradition is a minimal-meaning phrase that used to have an agreeable connotation because it allowed people who insist on emphasizing Christian influences to sound like they did not wish to exclude the Jews. But that was in the past. The Muslim immigration of our own moment means that, in America today, Islam has taken its place as a third main religion. To speak of the Judeo-Christian tradition in modern America is to make an ostentatious exclusion of the third religion.

Someone might point out that “Judeo-Christian tradition” does refer to something real—namely, to the grand tradition that draws not just on the great Christian thinkers but also on Maimonides or Rashi or any number of other Jews. In reality, though, the same broad tradition draws, as well, on Averroës and al-Farabi et al.—as Maimonides would tell us. Why not speak, then, of a Judeo-Islamo-Christian tradition? A phrase like that tripping multisyllabically off the tongue of a rabbi at the Republican National Convention would have been a noble thing. Rabbi Spero preferred to be for MAGA and the Muslim ban, as it were. Awful, I say.

By Sean Cooper

After so many days with the conventions, the dominant characteristic of the experience has been a sense of weightlessness that permeates the proceedings, a feeling of watching several hours of programming along with 15 to 20 million other Americans that only functions as a set of ideas and emotions if they are hardwired into the circuitry of the internet. It’s not a shared experience in the sense that others, too, are watching this as if it were a direct encounter with a political event. Or watching something that maps onto their actual day-to-day lived, sensory experience. I imagine in fact that what they are viewing is a kind of device that codes and decodes whatever their pattern of media consumption happened to have been over the last couple of days. In this way the conventions have become not an opportunity to comprehend political platforms but rather consumer skeleton keys that unlock the actual political ideas as they’re embedded by partisan media outlets into their daily news coverage.

It was said that John F. Kennedy was the first television president, and it would seem, despite the influence social media and digital news cycles played over the last several elections, that this campaign marks the first true internet presidency. For many still abiding by lockdown restrictions or various implementations of social distancing, the encounter with all major cultural and political events has become mediated not by a shared experience that is similar and understood alongside friends or family or colleagues or neighbors in close physical proximity of home, work, or wherever else, but rather entirely or quite nearly so through patterns of internet consumption. This reality has felt more entrenched and solidified over the past week and a half than it has for many of the other major cultural events during the pandemic, if only because of how distant and removed the convention speakers seem whenever they address my fellow Americans.

By Michael Lind

What have we learned from the two national party conventions this summer? We have learned several important things.

To begin with, both parties now consider the white working class to be the base of the Republican Party. This allows Republicans to take members of the white working class for granted and Democrats to more or less ignore them.

This is a development of historical importance. For half a century, to be sure, downscale whites have grown in importance in the GOP. But to judge from its policies and its messaging, before 2016 the identity of the Republican Party was still that of an upper-middle-class party of professionals and executives, with some “Nixon/Reagan Democrats” added as auxiliaries. That is no longer true. The Nixon/Reagan Democrats have taken over, among the voters if not the elites. The Republican Party’s core constituents are now non-college-educated working-class whites.

Meanwhile, the Democrats no longer bear any resemblance to the New Deal party of Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson—a white working-class party with some Yankee progressives and a growing Black constituency. The Biden Democrats are an alliance of upscale, college-educated whites—many of them former moderate “country club” Republicans—and African Americans. Reflecting this alliance, Democratic policy combines center-right neoliberal economics with race-based affirmative action and messaging of various kinds.

The finally completed electoral realignment of the two parties has left two categories of voters floating between the two parties: white Reagan and Bush Republicans, and nonwhite minorities other than African Americans.

Between the 1960s and the 2000s, when white working-class voters, alienated by the cultural liberalism of national Democrats but suspicious of Republicans, were the most important swing voting bloc, candidates of both parties tried to appeal to them. Nixon and his successors pursued their Southern Strategy and appealed to Northern “hardhats.” The only Democrats to be elected to the White House between 1968 and 2008 were two Southern white governors—Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton—who posed as folksy populists and distanced themselves from the cultural left. John Kerry made his bid for this swing voting bloc by boasting of his military record and going duck hunting.

That was then, this is now. For the moment, Hispanic and Asian American voters vote mostly for Democrats, though not at the near-unanimous rate of African Americans. In this election, both parties appear to consider moderate Republicans to be the most important swing voters.

The competition for the white suburban Republican mom, who has replaced the Midwestern blue-collar factory worker as the archetypal swing voters, explains why the Democrats at their convention paraded affluent anti-Trump Republicans. It also explains why the Republicans at their convention featured a number of female and nonwhite speakers with the intention apparently of reassuring white middle-class professionals that the GOP is not the fascistic white nationalist party of Democratic propaganda.

My guess is that the Democrats will be more successful at converting alienated Republicans than the GOP will be at winning them back. Indeed, since the Democrats have now replaced the Republicans as the favorite party of corporate, financial, media, and academic elites, it is likely that most elite Never Trump Republicans will simply be centrist neoliberal Democrats in another electoral cycle or two.

This gentrification of the Democratic Party may create a temporary Democratic majority. But the influx of affluent whites who combine social liberalism with wariness of taxation and government may destabilize the Democratic coalition, once Trump is gone as a unifying enemy in 2021 or 2025.

Already in the last few elections the Republican Hispanic vote has been growing, albeit from a low base. To achieve sustainable majorities, the Republicans need only add a sizable minority—not a majority—of Hispanic voters to their white working-class base.

But that possibility lies in the future. In this election, both parties are competing for alienated Reagan-Bush Republicans. They may swing this election. But they will probably not be swing voters for long.

By Noah Pollak

Every successful presidential campaign offers a simple, understandable message: Morning in America, Compassionate Conservatism, Hope and Change, Make America Great Again, etc. The Biden campaign’s official slogan is “Build Back Better,” but that’s not the real theme. He’s running on “a return to normalcy.”

But the rioting, looting, lawlessness, and police impotence on display in major cities is not going away on its own. These cities are not only run by Democrats, but are political-cultural hothouses completely dominated by the left flank of the Democratic Party, the progressives.

The progressives are unwilling to restore order, and the Democrats are unwilling to criticize the progressives. So when Biden finally weighed in today on the rioting in Kenosha, all he could do was offer a passive and vague opposition to violence that has no chance of altering the course of events. Send in the National Guard? Give the police the go-ahead to arrest rioters, and keep them locked up? He didn’t say.

He’s scared of the Black Lives Matter movement and the Bernie Bros, but perhaps he should be more scared of the normal people he needs to convince that he can deliver a return to normalcy. The DNC, with its emphasis on identity politics and social justice, and its refusal to address the chaos, only magnified the disconnect between campaign theme and political reality.

At least Trump is willing to talk about it and express indignation. And do more than talk—he sends in federal law enforcement and offers governors the National Guard.

And so voters are left with scenes like what happened yesterday in Washington D.C., where restaurant patrons minding their own business were accosted by a mob of deranged cultists demanding public displays of obedience to their demands.

There is a subtext to all this that a friend of mine who is very perceptive and does not work in politics pointed out. I will quote his email at length because he describes something I think a lot of people have started to feel but cannot yet articulate:

Ordinary Americans intuitively understand that they’re being held hostage. The message from the left, without anyone having to say it explicitly, is that the violence will end and we can return to our lives on the condition that we get rid of Trump. And if we don’t … Who’s to say how bad things can get?

I wish we could all afford to take the principled position that you don’t appease hostage takers. But that’s not real life. If you’re a normal person who just wants to send your kids to school, to get back to work, and for the riots to end, you know that those things can probably happen by Thanksgiving if you just give the left what it wants and get rid of Trump.

Liberals don’t even hide that this is the message. Just look at their convention last week. They spent it repeating, as if it were a mantra, that Donald Trump is an “existential threat to American democracy.” Nobody believes that. It’s literally crazy. But crazy is the point. We need to know that they just might be crazy enough to burn the country to the ground, and claim just cause for doing so, if we don’t give them what they want.

There is real danger here for Biden, because as events spiral out of control people will stop believing that “giving them what they want” will stop the chaos. The more people understand the chaos as a form of political extortion, the more people see that Biden’s response is meek and frightened of the mob, the more the idea of a return to normalcy will seem ridiculous. And then the basic justification for his candidacy will disappear.

I watched the second night of the Republican National Convention the same way you fall in love or go bankrupt: gradually, but then suddenly stricken by a strange and somewhat inexplicable premonition. It was this: Donald John Trump is going to win in November, and win big.

Yeah, I know all about the polls. I understand the deep distaste many Americans, including some traditional Republican voters, feel for the president. I am well aware of the criticism of his conduct in handling COVID-19, or the riots following George Floyd’s death, or any number of issues. And yet, as Trump’s first surprise election ought to have taught us by now, when it comes to modern American politics, the only principle that truly matters is the Ooga Chaka principle: We vote for the candidate who gets us hooked on a feeling and high on believing.

Last week, the Democrats used their convention to deliver three key messages: Joe Biden is a very decent person; Joe Biden is not Donald Trump, who is not a very decent person; and, being both a very decent person and not-Donald-Trump, Joe Biden is passionate about amplifying the voices of women and minorities, which is one important way to prove both your decency and your not-Trumpiness.

Who, precisely, might get hooked by these messages, and on what feeling? That Biden is a decent person is indisputable anywhere outside the airless quarters of the most quarrelsome partisans. That he shares little with the man he hopes to defeat is obvious—by now, Trump’s fans and detractors alike have very few misconceptions about the man’s character. That leaves us with the DNC’s heavy schmear of identity politics, a sentiment that doubtless resonates with the party’s educated, affluent base but says very little to those weary Americans who wonder why their cities are burning and why on earth anyone would ever want to defund the police.

The RNC, on the other hand, had a much more hearty offering on hand. It had no actors, singers, comedians, billionaires, academics, or former presidents present to offer perfectly polished paeans to character. Instead, it had people of faith affirming the singular importance of safeguarding the freedom of religion; immigrants affirming the notion, not controversial until very recently, that an American citizenship was an exceptional honor, not a universal right; blue-collar workers affirming the all-American reliance on small businesses, not tech behemoths; law enforcement officials affirming the foundational truth that, in America, when we disagree, we talk things over, not burn things down; and African Americans affirming the belief, central to the thinking of Martin Luther King Jr. and entirely alien to the current crop of race hustlers, that it’s the content of one’s character, not the color of one’s skin, that ought to matter.

In other words, whereas one party had the same narrow dogma repeated verbatim with very little variation, the other had—dare we say it?—diversity: of gender and of race and of experience, but also, more importantly, of interests and ideas.

This is not to say that watching both conventions will get a sizable number of voters to stop worrying and learn to love Donald Trump. But it is to say that it’s becoming increasingly more clear that the Democrats’ real problem isn’t the party’s aging candidate or its rambunctious left flank but, rather, its relationship with reality itself.

A party seriously interested in recapturing the White House would’ve done well to launch its bid by drafting a road map that roughly corresponds to America’s territory. It would’ve benefited from going long on big ideas and short on big personalities. It would’ve sought to vigorously court the millions who rejected it last time around, choosing instead to bet on an imperfect upstart. The Democrats orated, emoted, and fixated on nothing but the orange-haired object of their obsession.

To make matters worse, if you were watching the convention on TV—as fewer and fewer Americans do these handheld, device-driven days—you were treated to the dizzying but not altogether unpleasant experience of seeing the talking heads on cable news ask you to believe them rather than your own lying eyes. To hear the pundits tell it, the RNC is one part Thunderdome, one part plantation owners’ meeting, a series of dark and stormy nights dedicated to hating anyone or anything that isn’t white, rich, and smug. Examples are plentiful and sordid, but here’s one: After suing CNN and settling for an undisclosed sum, Nicholas Sandmann, the Kentucky high school student who was portrayed as a baby Grand-Wizard-in-training by our malicious media, appeared last night to tell his story. He was polite, earnest, and engaging but that didn’t stop our moral and intellectual betters from once again telling a very different story. Sandmann, sneered one cable news stalwart, was a “snot nose entitled kid” who was best ignored. That stalwart? Joe Lockhart, of CNN. There’s no better way to describe the last four years of American journalism than the mantra coined decades ago by Seinfeld’s showrunners: No hugging, no learning. And, like Seinfeld, all MSNBC, CNN, and their likes can produce these days are shows about nothing.

For better or worse, Americans want something—anything—else. Many dislike Donald Trump, and so will not vote for him no matter what. But many more, when in the privacy of the voting booth, will do what voters so often do and vote for the party that looks—and feels—more like them, and that can get them high on believing in an America that looks like the one they know and love—an imperfect but good nation ever slouching toward a brighter tomorrow. These last two nights, the RNC has made a very convincing case why that party may very well be the party of Abraham Lincoln and Donald Trump.

By Jonah Raskin

Donald Trump was supposed to dominate the Republican Party Convention. No matter where one sliced the American pie, he was supposed to be there bigger than life. But on the second night of the convention it wasn’t the president himself who stood out above everyone else, but rather members of his family, including his daughter Tiffany, who talked about God, miracles, and masks (she was against them), and his son Eric, who accused the Democrats of “sucking up to the elites in Paris.”

With speakers like Cissie Graham Lynch, the daughter of Billy Graham and an evangelical, the Republicans reached out to their rock solid base, and with teenagers like Nicholas Sandmann from Kentucky—who denounced “cancel culture” and spoke in favor of the “unborn”—they appealed to young voters sitting on the fence.

Then there was The Donald’s wife, Melania, who was a near-perfect speaker as the first lady, the mother, and as an immigrant who became a proud citizen. Growing up under a communist regime in Eastern Europe, she came to the United States to seek “freedom and opportunity,” as she called it, and amplified the key memes of the night.

That night was a lot about what I’d call “defectors,” “renegades,” and “dissenters,” including individuals who started out as Republicans and became Democrats, Black people who broke racial ranks and affiliated themselves with a party led largely by wealthy, white men.

Defector Melania escaped from behind the Iron Curtain and embraced the American dream. In the Rose Garden, she spoke for 28 minutes and sounded like she could hold forth for another 28.

Abby Johnson described her journey from an abortion clinic where she worked, to becoming an anti-abortion activist. Retired Superior Court Judge Cheryl Allen explained that she didn’t even know the name Donald Trump in 2016, but now considers herself a loyal member of the team. Jeanette Nunez, the lieutenant governor of Florida, portrayed herself as the daughter of freedom-loving, anti-Castro Cubans who came to the United States to make their own fortunes unimpeded by commissars.

The second night was in many ways about the “free world” versus the world of the global gulags, a dichotomy that the United States emphasized during the Cold War, which might or might not still be a reality, depending on where you look and what you find.

The New York Times has the muscle to dig beneath the surface and point out what many other news organizations can’t or won’t do. At the end of the second night, “Melania’s Night,” the Times offered a comprehensive analysis of “misleading, exaggerated, and false statements” made by Republicans on issues like immigration and immigrants, tax cuts and the opioid epidemic. In the eyes of the Times, the Republicans stretch, bend, and break the truth.

But listening to their speakers, one might well conclude that they belonged to the party of “fact,” while the Democrats belonged to the party of “narrative,” that Republicans disseminated the truth, while Dems spread misinformation and disinformation.

What’s real and what’s not real? And when will we wake from the dream?

By Jacob Siegel

Unexpectedly, I found that there was something moving and unsettling about Melania Trump’s speech last night.

The Republican convention has been surprising in a way that the Democratic convention was not. Surprising because it has been more stately and effective than expected and also because the tenor has felt reasonably true to the spirit that first captured Trump’s base, but without being so fully authentic that it summons back the pagan excitements of the 2016 berserker campaign.

I don’t know that I have ever really noticed Melania before. I had held her in my mind as a punchline, a tabloid figure, a stock image occupying the space on-screen alongside the president reserved for a rich man’s idea of a beautiful woman.

Bette Midler was wrong, obviously, to say that Melania cannot speak English. But don’t cancel Bette just yet because all she meant to say was that the first lady sounds funny when she speaks, which is obviously true, but she did not say that because it would have been rude. (It’s also rude to say that someone speaking perfectly lucid English cannot speak the language—even if that person is Donald Trump’s wife—as Midler now acknowledges). Melania’s speech was in English but she herself would say, EEngleesh. Some accents are funnier than others. In an alternate universe where slovenly intellectuals had their pick of mates, Melania might have married the philosopher-king Slavoj Žižek, a fellow Slovenian whose accent produces the same funny vowel sounds as hers but in a more phlegmy and neurotic register and who also shares certain temperamental habits with her current husband, the president. But instead, Melania was here, an American and a Trump, the first lady of the United States, giving a speech for which, perhaps, her life had not fully prepared her, and which, yet, she delivered with a disarming poise that, by leaving so much to the imagination, managed to be captivating.

“We must make sure dat weemen are heard and dat American dream continues to trive.” She looked about impassively as she spoke. Her face does not move much aside from the mouth but swivels on the neck. The eyes alone are expressive and restless. And that is what makes it moving in its way because it is unexpected and incongruous. Melania speaking to the American dream, common to all who have ever aspired to come to the land of opportunity and make it big in the fashion industry (or some other industry perhaps).

By Jonah Raskin

I live in Sonoma County, California, a rural place with real farms and real farmers that has been solidly Democratic for decades, though it had a long Republican past that I experienced when I first moved here from New York in the mid-1970s. Today, most of my neighbors are Democrats who lean toward Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, though they’re now behind Biden and say they will vote for him in November.

I’ve had acquaintances who’ve lived in secluded mansions and who have had autographed photos of George W. Bush in their living rooms. That was an eye opener!

These days, I have friends who are Republicans and who have taken me to meetings of the local Republican Party. The members—Caucasians, white- as well blue-collar workers, women and men, everyone over the age of 50—wore Trump hats and American flags and on most issues were definitely conservative. They were against the legalization of marijuana, didn’t like immigrants, and were in favor of a wall along the border with Mexico. “Build walls, not bridges,” one woman told me.

My friend “L,” as I’ll call him, watched the Dems during the third week of August and then the Republicans beginning at the start of the fourth week of August. I talked to him on the second day of the RNC. I wanted a reality check.

“Trump is gonna smoke Biden’s ass,” L told me. “I don’t understand why the Dems couldn’t select someone better than him.” When I asked L why he was a longtime registered Republican (he’s also a college graduate and a successful businessman), he said, “I don’t think the government should be involved in people’s lives, unless goods and services can’t be provided by the private sector.”

He’s not against what might be called graft. “If you’re hitting a wall and need to get something done,” he explained, “you pay someone off, under the table. That’s the way things were done when I was a boy growing up in Suffolk County, New York, where my father was a lawyer and for a time a registered Republican.” It was the only way to operate in a solidly conservative environment, he told me.

L’s wife, who is also a friend of mine, is a Democrat and supports Biden. She and L rarely if ever talk politics, though they’ve been together, seemingly happy, for decades.

L likes Trump, he told me, because “he has great one-liners which solidify his unwavering base, and because he actually gets good stuff done that he doesn’t get credit for.”

He described Trump as “a slightly smoother version of Teddy Roosevelt who speaks loudly and beats a stick when he wants and needs to do so.”

The American white working class, L told me, has never had it so good, though not in terms of salaries and incomes. “They have more leisure than ever before, TVs and computers are dirt cheap, plus they have freedom of movement around the country, something that people in other nations don’t have. Also they can bitch and moan about folks who don’t work and that they can dismiss as lazy.”

From L’s point of view, 2020 America was close to being the best of all possible worlds. There was no point switching allegiance.

By Paul Berman

The music at the DNC last week was, in retrospect, great. And at the RNC so far it is schlock. This leads me to hope yet again that the Democrats will prevail; and to worry that maybe they won’t.

Billie Eilish premiered a song at the DNC, which is remarkable all by itself. Music at the DNC used to consist of ever-repeated renditions of Franklin Roosevelt’s campaign song of 1932, “Happy Days Are Here Again,” which served as a quadrennial reminder of how depressed was the Great Depression. I cannot say that Billie Eilish made a positive impression on me, at first. The green hair was not to my taste, nor did green hair seem to me politically advisable. She delivered a little speech that was preachily annoying.

And yet, her song proved to be—well, it was intriguing. A long, nearly arrhythmic and melismatic introduction, demanding patience from the listener, as if the introduction were an undisciplined self-indulgence, except that something in those melismas was, in fact, disciplined—leading to a disco beat of sorts, over interesting changes—and then back to the introduction. The song was not an insult to the ears or the brain. It was intelligent, a little mischievous, and somehow moving. An artful song. I was glad to have listened.

Prince Royce performed a video version of Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me” to a bachata rhythm, in English and Spanish, filmed against an industrial background. His performance had its virtues, too, even if the scale of ambition was smaller than Billie Eilish’s. But the main event was Jennifer Hudson performing a genuinely novel arrangement of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” with a band consisting of two pianos and a soprano sax. Her performance was overwrought, but that is not the worst of sins. It was the accompaniment that made the performance interesting—that brought it to the edge of classical art song, acoustically authentic, not based on electronics.

Does any of this have to do with politics and the Democratic Party? I discover that, in my own imagination, it does. The performances remind me that, for all the disasters of right now, America possesses a brilliant culture, creative and sophisticated. Wouldn’t it be great to have a White House that knows how to celebrate and preside over such a culture?

At the RNC, by contrast, the music that I have heard has so far consisted of soundtracks from what I suppose are Hollywood Westerns—big swelling gobs of violin harmonies, expressing grandeur: music suitable for the moment when the hero and his horse pause on the ridge above the valley, and the two of them gaze on the magnificence of the untamed West, or the sunrise, or something. Can there be anyone who associates grandeur with Donald Trump? Yes, such people exist. They must find the music thrilling. My own patriotic heart pounds a little at the creativity of the artists who were featured at the DNC, and I am certain that masses of other hearts pound patriotically at the gobs of soundtrack schmaltz.

But which population is larger—the art-song population, or the soundtrack schlock population? Thank you for not answering.

By Armin Rosen

The differences between last week’s Democratic confab and the RNC are instructive even at the level of their physical setting. The Democrats held much of their convention in a TV studio, with a different celebrity hosting each night. The Republicans are holding theirs in a grand colonnaded hall, with rows of American flags and the acoustics of the Capitol rotunda. The Democrats hinted that their party’s soul lies in the media as both a culture and a project—i.e., in the elite exercise of shaping everyone else’s perception of reality. The Republicans revealed that their soul lies in patriotic gesture, which isn’t necessarily any less empty or less sinister than what the other party’s offering. In fact, the flags-and-columns get-up is more sinister, if you’re one of those people who reasonably fears the coercive possibilities of nationalism joined to political power more than they fear the reality-shaping abilities of whoever controls the culture.

Anyway the real contrast that I obsessed over on Tuesday night wasn’t between the two parties but between the RNC and the 2018 German-language movie “Never Look Away.” Of course Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Oscar-nominated, third feature film isn’t nearly as good as his debut, the sublime “The Lives of Others.” But his panorama of 20th-century German history, told through a fictionalized version of the artist Gerhard Richter, is still the rare three-hour film whose length is barely felt.

The movie hinges on an abortion: Somewhere in hour two, the Richter stand-in impregnates the college-age daughter of a medical doctor and former high-ranking Nazi who is now a health official in the fledgling East German regime. Much of the movie’s subsequent drama is obliquely tied to whether it is possible for her to become pregnant again, with this possibility or impossibility then answering the question of whether Germany can ever emerge from the horrors it inflicted upon itself and upon humanity. The woman’s father is an unreconstructed Nazi-type racial purity goon, and sees the abortion as a sad but necessary duty to his family and to the volk. He performs the procedure himself, but the viewer doesn’t get to see it. This is in remarkable, unavoidable, and maybe even deliberate contrast to the gassing of a group of mentally ill women during the movie’s first hour, which we do get to see.

Said gassing was somewhat gratuitous to the larger plot, whereas the abortion was the entire plot. It’s safe to assume that in a movie literally entitled “Never Look Away,” there is deep, intended meaning in the choice of what is and isn’t shown to us. But maybe it’s simpler than that. Maybe von Donnersmarck figured that even art-house audiences, for reasons I’d rather not probe at the moment, are more sickened by an on-screen abortion than they are by an on-screen massacre of the lame.

Yeah, so back to the convention. The most striking speech of last night was by Abby Johnson, a former abortion clinic director with semilunatic views on things like universal suffrage who went on to found a pro-life group. She launched into one of the most graphic depictions of abortion I’ve ever heard in any context, never mind a political convention with potentially tens of millions of people watching. “A physician asked me to assist with an ultrasound-guided abortion. Nothing prepared me for what I saw on the screen: An unborn baby fighting back, desperate to move away from the suction,” Johnson recalled. “The last thing I saw was a spine twirling around in the mother’s womb before succumbing to the force of the suction.” There was no looking away in Johnson’s speech, and the listener did more than just see. “For me abortion is real. I know what it sounds like. I know what abortion smells like. Did you know abortion even had a smell?”

There is no reason Johnson’s speech should necessarily have any bearing on where one stands on abortion, which is divisive both between people and within people. Abortion raises issues of natural and legal rights, personal choice, and social utility that are arguably disconnected from the alleged brutality of the procedure itself. But at least Johnson’s listeners now have a better idea of exactly what it is they oppose or support.

Johnson’s speech was a jarring moment of truth in the midst of a nastily occluded political season. You don’t expect the abstractions to suddenly crumble in the middle of a partisan political convention, which is nothing but abstraction—especially this year, when the conventions aren’t grand civic gatherings but television shows. Politics in general suffers from layer upon layer of abstraction: American bombs detonate thousands of miles away; people die of heroin overdoses in towns we’ll never visit, or they catch the coronavirus in meatpacking plants or prisons or nursing homes or other forgotten places. The suffering that government policies cause is often invisible to the average American, and in the Trump-era reality has been kept at a particular arms length. How disorienting to see it come roaring back in the context of a pitch for Trump’s reelection, and on something that even a very bold artist recently decided you were better off not seeing.

By Sean Cooper

For the DNC and the RNC both, there is no better argument against four nights of these conventions than watching two consecutive nights of so much filler, repetition, and misrepresentation. Four hours of this stuff drains oxygen to the brain, the arteries pinched by the radical clumsiness from the left and the extreme dishonesty from the right.

To just pick one highlight, there’s been an ongoing disinformation riff throughout the RNC on the opioid crisis (we can leave aside for now the overlapping reefer madness, which included Natalie Harp’s incoherent night 1 conflation of the Democrats’ advocacy for “marijuana, opioids, and the right to die with dignity—a politically correct way of saying assisted suicide.” Ryan Holets, a New Mexico police officer who adopted the unborn daughter of a pregnant heroin addict he met while on patrol, spent his segment last night extolling President Trump’s “leadership on fighting this deadly enemy.”

“In a move that strikes at the root of the problem, he implemented a safer prescriber plan aimed at reducing opioid prescriptions by over a third over three years,” Holets said, praising Trump’s $6 billion in federal funding. “Drug overdose deaths decreased in 2018 in the first time in 30 years. Many states the hardest hit by the opioid crisis are seeing the largest drop in deaths.”

Credit to the RNC speakers who, unlike their DNC counterparts, hardly addressed the issue. But Holets’ representation is rather disingenuous.

As I mentioned before, while drug overdoses decreased slightly in 2018, synthetic opioid overdoses were on the rise in 2019, and overdose numbers during the pandemic have dramatically surged. Holets’ claim that Trump’s effort “strikes at the root of the problem” is false in that shifting the death count from pills to another column does not solve the problem, nor does it address the collapsed blue-collar industries, offshoring, and disintegrating social institutions that have instigated the hundreds of thousands of overdose opioid deaths nationwide.

Of the states hardest hit by the crisis, which Holets claims are seeing the largest drop in overdoses, just look to Delaware, which had the second-highest rate of death in 2018. The state’s health department reported that in May Delaware saw a 60% spike in overdoses from the previous year, which some officials attribute to the COVID pandemic and how it exacerbates those very root issues that Holets argued have been fixed by Trump’s prescription plan.

There are many problems with such misinformation, not least of which is that declaring the opioid crisis solved stigmatizes those who continue to suffer from its ravages, leaving them to truly feel like the “Forgotten People”—here we might ask, forgotten by whom?—and who in whatever case have become symbols in Trump’s campaign to rescue America from his own administration.

By Tony Badran

Of all the memorable moments of the first night of the Republican National Convention, and many of them were memorable, the one line that stood out for me came from Kim Klacik when she referenced “the American spirit.” More to the point was how the American spirit was defined as a spirit of optimism and freedom, grounded in the recognition and celebration of America’s exceptionalism.

During his keynote at the DNC last week, Barack Obama defined the immigrant experience in America through the lens of grievance and resentment, portraying it as a clash between the fake allure of America and its supposed reality of unfulfilled promise and toxic hate. What Americans have in common, Obama suggested, is that we are all victims of the brutal hatreds that emanate from the core of the American project itself:

“Irish and Italians and Asians and Latinos told: Go back where you come from. Jews and Catholics, Muslims and Sikhs, made to feel suspect … Black Americans chained and whipped and hanged. Spit on for trying to sit at lunch counters, beaten for trying to vote … They knew how far the daily reality of America strayed from the myth.”

While Obama’s sense of grievance was nothing if not inclusive, I can’t help hearing the ex-president’s rhetoric of sectarian resentment in the context of my own upbringing in Lebanon—a country in which such push-button incitement was the lingua franca of national politics. It is weird and more than a bit scary to hear this kind of language being mainstreamed in America by a former president who spent part of his childhood in Indonesia. It’s even weirder to hear and watch the Ivy League graduates and professors who comprise the Acela corridor, foreign-policy elite themselves engage in this kind of rhetorical Third World blackface, purporting to represent American interests by turning American politics into a mirror image of the places that they write about, and sometimes visit—and that some of us are lucky enough to have escaped.

In part, the use of Third World sectarian language and political categories and the Democratic Party is a utilitarian one: It allows the party to negotiate between its ostensible role as a “working-class” party and its advocacy for global free trade agreements and open borders which harm American workers. “Celebrating” the cultures from which immigrants come as inherently virtuous, while painting America as monstrous, allows Obama and his party to “speak for immigrants” while eliding the actual effects of the policies they champion on people who actually live and work in America. In doing so, they are cultivating the worst aspects of the political cultures that immigrants like me fled and denigrating the virtues that attracted us to America.

Candidly, my own immigrant experience—the experience of hundreds of immigrants like me, who I know personally and live alongside in Queens—is much closer to what I heard at the RNC, which explicitly rejected the “1619 Project” worldview of America as inherently toxic and sinful, and celebrated what brought us here. And so—speakers stressed not the segregation of identity politics but integration into an America whose uniqueness lies in large part in its rejection of identitarian idiocies in favor of a universalist humanistic vision of citizens who are possessed with inviolable rights, which may hopefully allow us to freely define ourselves and shape our own destinies.

Consequently, there was also a welcome tone of caution about the threat of descending into the cesspool of Third World politics. Rep. Jim Jordan laid out the dangers of the very Third World Russiagate information campaign and the fake impeachment proceedings that followed. Targeting not just the president, but also the very integrity of the republic, the tactics that made the Russiagate wheels turn are new here, but they are familiar to anyone who fled from the Middle East, Africa, or Eastern Europe.

Jordan also spoke powerfully of the violence inflicted on American cities by wannabe partisan militias, the steady erosion of individual freedoms and rights, the attack on religious freedom, and its substitution with progressive party doctrine, and the ongoing attack on the Second Amendment—all of which resonated strongly with me, and I suspect with anyone whose experience of “politics” goes beyond social media and Zoom conventions.

That this message resonates on a fundamental level with Americans of all races and national origins, regardless of immigration status, is evident in the surge of gun sales over the past several months. Far from being a sickness, America’s “romance” with guns strikes me as a sane recognition, borne out of hard experience, of the brute fact that a free people is one which can protect itself.

All of these lessons, which have been repeated in too many countries at too many moments in history to bother reciting them here, seem to baffle and anger educated American urbanites—who in any event are largely prohibited from owning guns. Yet they are lessons that many immigrants to America, both young and old, have had the misfortune of learning firsthand, and are therefore unable to forget. Comedian Dave Chappelle sort of alluded to this fact last year with his line that the Second Amendment “is just in case the first one doesn’t work out.”

Chappelle did not quite nail it, though. The point is, without the Second Amendment, the first is always at the mercy of someone else: the party or the state. Perhaps that’s the biggest difference between the competing visions of America we face today: the choice between celebrating and cultivating the uniquely American spirit of personal freedom, or celebrating the dictates of America’s callow, wannabe commissars.

The first national political convention I ever covered was excellent preparation for reporting on politics in the Trump era. I just didn’t know it at the time. The year was 2012 and Tablet had the crazy idea to send a kid fresh out of college to cover the nation’s biggest political events—the Republican and Democratic conventions. So instead of sitting in the office and correcting the typos of veteran reporters filing from the scene like most fledgling journalists my age, I was thrown into the fire and tasked with churning out daily dispatches as Mitt Romney and President Obama accepted their respective nominations.

What you quickly learn when witnessing one of these conventions on the ground, instead of just watching the highlights on TV, is that most of the proceedings on stage are actually incredibly boring. Before the coronavirus forced parties to crunch their content into a few hours, convention speeches by B-list politicians and functionaries would begin in the morning and drone into the evening, at which point the big acts would finally take the podium. The boredom was intentional: Each convention was heavily scripted, with speech after speech carefully crafted to echo the same themes for any voter who might tune in at any moment. Taglines like “you didn’t build that” would repeat again and again, ensuring that whenever someone turned on C-SPAN, they’d get the message.

Which is why it was so incredibly shocking when Clint Eastwood got up on stage at the RNC and just started talking to a chair. For those unfamiliar, the fabled film director was given a prominent slot in prime time to speak in support of Romney. But unbeknownst even to convention organizers, he didn’t intend to deliver a traditional speech. Instead, after some brief opening remarks, Eastwood began a quasi-coherent dialogue with an empty chair meant to represent President Obama.

I was there, and I remember the distinct feeling of oxygen being sucked out of the room as people realized what was going on. At first, they thought it was a joke and laughed somewhat incredulously; then they realized that Eastwood was serious, and was going to continue talking to an inanimate object for some time. After hours and hours of vetted and scripted content, the convention had officially gone rogue. For the first time, no one knew what was going to happen next. This was funny, exhilarating, and also terrifying. Some seven minutes later, Eastwood concluded his rambling exchange, and gravity reasserted itself. The speeches went back on script, the focus-grouped formulations returned, and the professionals retook the stage.

At the time, everyone laughed off the Eastwood incident as an amusing aberration. But as it turned out, it was a harbinger. Because just four years later, a politician whose entire career and appeal was built on refusing to stick to any semblance of a script was elected president of the United States. And Donald Trump’s tenure has been one long empty chair moment that refuses to end. “He can’t say that!” “Oh, he did.” “And now he’s doing it again.” Rinse and repeat for four years. Like Eastwood’s antics, it has been impossible to look away from Trump’s performance, even as the consequences have been dire—improv comedy turned to tragedy.

In many ways, Joe Biden is betting his campaign on the idea that while the occasional empty chair moment can provide some comic relief, nobody actually wants to live inside of one. People want politicians who stick to their scripts, do not demand our constant attention, and have professionals running their Twitter accounts to put out fires, rather than start them. Biden has been almost studiously boring, something that did not endear him to internet partisans in his own party, but has served him quite well with the electorate. He even used a script while filming the call with Kamala Harris in which he picked her as his running mate. The Trump campaign gleefully pointed this out, not understanding that it reflected a feature of Biden’s appeal, rather than a bug.

What Trump’s team fails to grasp is that what might have seemed entertaining or even exciting to some voters during a time of relative prosperity in 2016 feels quite different in an era of pandemic and economic implosion. In 2020, “off script” is just another way of saying “out of control.” From the outset, Biden read the electorate’s exhaustion, and promised it instead the comforting cadences of professionalized politics.

After four seasons of the 24-7 Trump reality show, with the protagonist ranting at empty chair after empty chair, Biden is betting that the American people are ready to change the channel. Come Nov. 3, we’ll find out if he’s right.

By Jonah Raskin

On the opening night of their convention, the Republicans came out swinging, kept on swinging all night long and stayed on message again and again with the voices and the faces of women like former Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley and South Carolina’s Black pro-Trump Sen. Tim Scott, along with African Americans like Herschel Walker, the football great who described Trump as his friend. One might have thought that the Republicans, rather than the Democrats, were the party of the underdog, the workers, the bullied people of color, rather than the party of Wall Street and the corporations.

On The Late Show, Stephen Colbert will try to ridicule Trump and his crew, but they’re not easily ridiculed. Every speaker carved out his and her own territory and turned unique phrases, but what they said added up to the same big picture: America and the American people are confronted with an enemy that’s both inside and outside, an enemy that wears the mask of the Democratic Party, and the smiling face of failed Washington insiders like Joe Biden.

Charlie Kirk, 26, the founder of Turning Point and a conservative activist, described Trump as “the bodyguard of Western civilization.” Trump has the heft and he also has the forces at Homeland Security.