The full Tablet series featuring Paul Berman’s original three-part essay on the state of the contemporary Left, along with responses to Berman from writers across the political spectrum, is collected here.

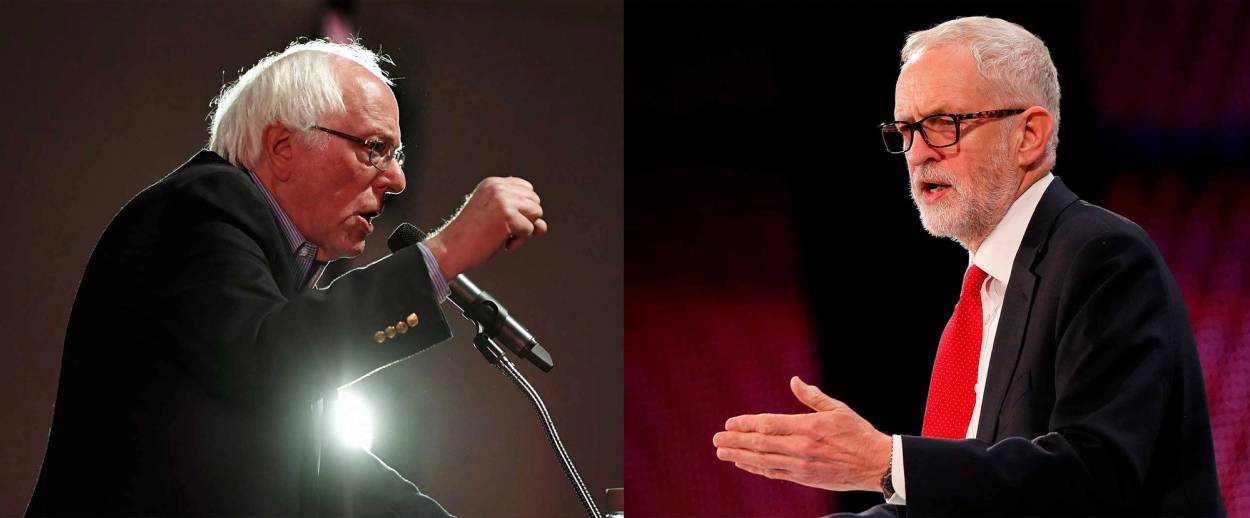

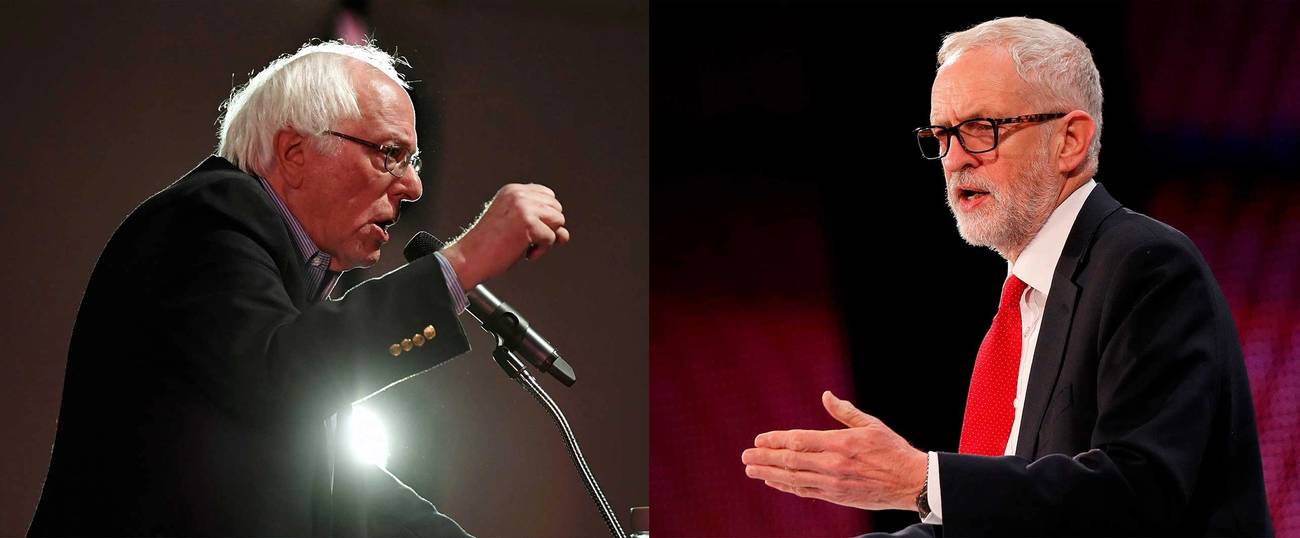

Just a few years ago the emergence of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and Democratic Senator Bernie Sanders in British and American political life would have been unthinkable. Until the financial crisis of 2008 mainstream social democracy had effectively surrendered its radicalism to the dictates of the free market. Yet now that it has returned, the crucial differences between the rival socialist traditions offered by Corbyn and Sanders are being lost in a media and political landscape bent towards oversimplification. Both men belong to a broad socialist lineage in common but you could as easily lump Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump together as proponents of democratic capitalism. Just as there are Republicans who repudiate Donald Trump, there is more than one form of socialist-influenced politics that is making a comeback.

As Paul Berman notes in the first part of his perceptive series of essays on the left and the Jews, “there is pressure on the Western left to accommodate, in the name of anti-racism and Third World solidarity, as many Islamist principles as possible, in regard to blasphemy, gender roles, and the iniquity of the Jews.” This is an apt description of the political tendency that Corbyn represents but it does not apply Sanders. Nor does Berman suggest it does but it has become a commonplace among political commentators to conflate the two distinct forms of socialist tradition. In so doing, they obscure a vital distinction in the political choices we face and Corbyn and Sanders have fundamentally different ideas of what politics should accomplish and whom it should serve.

There was no precise moment when socialism returned to fashion in the Anglo West but it had been apparent for some time that capitalism as we know it is broken. In the United States, today’s real terms average wage has the same purchasing power as it did 40 years ago. In Britain, the average wage packet in 2023 will still be 20 pounds lower than it was before the start of the 2008 crisis. Moreover, while British property owners have seen the value of their assets shoot up in recent years, 4 in 10 young adults can no longer afford even the cheapest homes in their area. As the economist Thomas Piketty has noted, we live under a mode of production that increasingly favors those who make money through collecting interest on assets rather than earning it through income paid for their labor.

With this in mind, the resurgence of socialist politics ought perhaps to have been foreseen. Yet it wasn’t—giddy as many were on a triumphalist narrative of liberal democracy that blinded them to those who, in ever greater numbers, were being left behind. Indeed, that the return of socialism was so unexpected has led contemporary commentators to skirt over the differences between its two most prominent western exponents, Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn.

The rise of the senator for Vermont who challenged Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination in 2016, and almost won, captures a paradox of our times. Sanders rose to prominence in a country that usually rejects class politics. Indeed, it is Britain that is frequently depicted as a more class-divided country than the United States. “England,” George Orwell wrote in 1941, “is the most class-ridden country under the sun. It is a land of snobbery and privilege, ruled largely by the old and silly.” Yet Sanders comes from a tradition of politics that views class as the most significant division in political life. And this has arguably been his strength as a candidate, with his attacks on Wall Street and the ‘1 percent’ striking a chord, especially among the young.

Sanders’ draws political inspiration from Eugene Debs, a five times socialist candidate for the presidency and militant trade unionist who once ran for office from an Atlanta prison cell. In 1979 Sanders provided voice-over for a documentary in which he named Debs “the greatest leader in the history of the American working class.” Sanders’ fealty to Debs was discernible more recently in his campaign for the Democratic nomination. Like Debs before him, Sanders’ strategy was to win by losing. The purpose of the Sanders campaign was not so much to capture the presidency–an unlikely feat–but to drag the mainstream of the Democratic Party to the left. Sanders also took from Debs a rejection of any leadership cult. “If the workers are dependent on some famous leader to take them into socialism,” Debs wrote, “then some famous leader will come along a few years later and lead them right back into capitalist slavery.” Thus Sanders described his Democratic challenge to Hillary Clinton as “not really about Bernie Sanders” but about “transforming America.”

To be sure, Debs’ version of class politics was always peripheral to the American mainstream. Debs lost heavily each time he ran for the presidency–his best result saw him win just 6 percent of the vote in 1912. Moreover, Debs’ reputation was sullied by a remark he made in a 1903 essay “The Negro and the Class Struggle,” in which he came across as unconcerned with the struggles of black America. “We [the Socialist Party] have nothing special to offer the Negro,” Debs wrote. According to his biographer Ray Ginger, Debs “refused to concede that poor Negroes were in a worse position than poor white people.” It wasn’t necessarily that Debs was unconcerned with racism–though his laissez faire attitude towards certain forms of it arguably derived from his status as a white man. Rather, he viewed bigotry and prejudice as “the foul product of the capitalist system.” In other words, there would be no end to racism until capitalism was overthrown.

Sanders has been similarly attacked for his emphasis on economic exploitation over questions of identity and racial justice. Black Lives Matter activist Marissa Johnson, who protested a Bernie Sanders rally in Seattle in 2015, labelled Sanders a “class reductionist.” “[Sanders] never really had a strong analysis that there is racism and white supremacy that is separate than the economic things that everyone experiences,” she said, echoing a standard liberal complaint.

Nearly 80 years after Orwell’s attack on the class divides of wartime England, it is in England that the left is attempting to slough off any class-based narrative of political life. As the political commentator Stephen Bush put it in the London Timesof August 2018, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn “doesn’t care about the United Kingdom all that much.” Indeed, Corbyn is far more interested in events taking place in the global South than he is with the former industrial heartlands in the North of England.

In one sense Corbyn’s politics are, like Sanders’, a throwback to an earlier incarnation of the left. But in far more significant respects, the two men belong to separate, competing traditions within the left that have given them incompatible political visions.

Corbyn is often characterized in the British media as an unreconstructed Bennite, the name for a follower of Tony Benn, the longtime standard bearer for Labour’s Democratic Socialist wing. But Corbyn is no Bennite. He is actually a product of the revisionist New Left that emerged in the 1960s. Despite surrounding himself with several hard-line Stalinists—both Seumas Milne, Corbyn’s director of communications, and Andrew Murray, Corbyn’s chief of staff, have written defenses of the Soviet Union—Corbyn, to his credit, has never been an apologist for the former socialist bloc. Indeed, in 1989 Corbyn was one of just four MPs who signed a parliamentary motion welcoming the “magnificent movements in Eastern Europe” against the “corruption and mismanagement of the Stalinist bureaucracy.”

Instead Corbyn has always looked to more exotic realms for inspiration. The 69-year-old is a man of his generation, attracted to Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh over Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker. He left formal education a year before the uprisings of 1968, a year when “an invigorating fever gripped the world,” as his old friend Tariq Ali has put it. If 1968 was defined by anything it was opposition to the dominant ideologies of both East and West. Of course, there were still unreconstructed elements of the hard-left that extolled the virtues of the health systems of East Germany and labelled the nascent uprisings against Stalinism in Eastern Europe “reactionary,” including Corbyn’s favorite newspaper, The Morning Star. But by the time Corbyn was a teenager, much of the activist milieu he grew up with had turned its attention to Cuba, Maoist China and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) for inspiration. This new orientation, which differed from the old Communist’s left’s deference to the Soviet Union as the center of the world, came to be known as Third Worldism.

Thus while Corbyn had few illusions about Moscow, he developed a habit of throwing his weight behind other dubious causes. Here the differences with Sanders are perhaps the most striking. Corbyn eulogised the late Venezuelan autocrat Hugo Chavez as someone who “made massive contributions to Venezuela & a very wide world.” Sanders has been criticized for a 1980 interview in which he praised the “revolution of values” supposedly taking place in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. But when grilled about his past comments about Cuba during a Democratic debate with Hillary Clinton in 2016, Sanders, sounding quite unlike a Third Worldist He called Cuba “an authoritarian, undemocratic country” and added, “I hope very much, as soon as possible, it becomes a democratic country.” This was in contrast to Corbyn, who eulogized Fidel Castro after the Cuban dictator’s death in 2016 as “a champion of social justice.” Sanders was also unequivocal in his condemnation of Chavez, describing the Venezuelan leader as a “dead communist dictator.”

Corbyn on the other hand has long carried a torch for ‘anti-imperialist’ terrorists and bigots. During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Corbyn invited members of the Provisional IRA to the British Parliament at a time when the organization was still bombing and shooting people. In 2014, Corbyn attended a ceremony in Tunisia that honored the perpetrators of the 1972 Munich terror attack. He also invited representatives from Hamas and Hezbollah to Parliament and was a regular guest on Iran’s Press TV (until it was banned from broadcasting in the U.K. by OFCOM) as well as Russia Today.

Corbyn himself is not of a theoretical bent. Yet the Labour leader’s career-long flirtation with militant, religious fundamentalists—so long as they are anti-Western—fits perfectly with the political tradition he was blooded in. For Corbyn, opposing Western military action and political hegemony requires soft-soaking the West’s enemies, whatever they happen to profess as their own cause. This is where the New Left and its fixation on the global South blends with the toxic, residual legacy of Stalinism. The lionization of authoritarian regimes like Cuba, Venezuela, and even North Korea, by Corbyn and his allies derives from the notion that any society with nationalized property, however repressive and backward, is a historical advance on the capitalist West. Meanwhile, Corbyn’s reflexive solidarity with “national liberation” movements, regardless of whether they are anti-Semitic or harbor bigots, owes to the overriding fact that they oppose Western imperialism. This extends to movements which do not wish to liberate people but enslave them, such as Islamism.

Sanders’ class-rooted politics has its faults, including an occasional monomania. But historically it has been far better at avoiding the trap of crude anti-imperialism that afflicts romantic Third Worldists such as Corbyn, who throw any class analysis out the window when it comes to movements that oppose the United States and Israel. On a psychological level the Labour leader seems to share the vicarious attraction certain mild-mannered left-wing men have for the allure of revolutionary violence. Of course, Corbyn may have been on the “right side of history,” as his supporters like to claim, from time to time. But then, if you have opposed everything the West has done for 40 years, you are invariably going to be right occasionally.

There can be little doubt that Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders have each tapped into a widespread disillusionment generated by the failures of free-market capitalism. Yet the two men come from distinctive political traditions that, if brought to power, would create very different societies and impacts for the ordinary people who lived within them. Look to the past to understand the present; and look at where today’s socialists came from to understand where they wish to take us.