What Progressives Should Learn From the Left-Wing Anti-Semite Challenging California’s State Assembly Speaker

Maria Estrada promotes Louis Farrakhan and attacked a Jewish politician over his religion. She also claims she’s just ‘anti-Zionist.’

It’s been a good election cycle for anti-Semites. From Illinois’ Arthur Jones to Wisconsin’s Paul Nehlen, the rise of neo-Nazis on the fringes of Republican politics has been ably chronicled by reporters like Jane Coaston at Vox and watchdog groups like the Anti-Defamation League. As if that was not enough, this week, another anti-Semite emerged in a prominent political race, this time across the aisle.

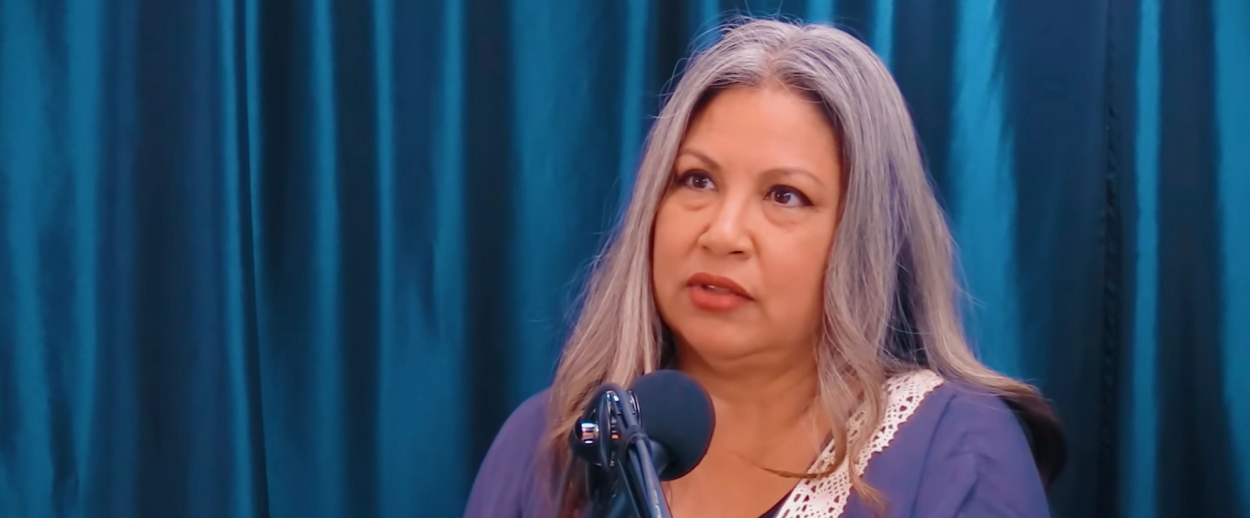

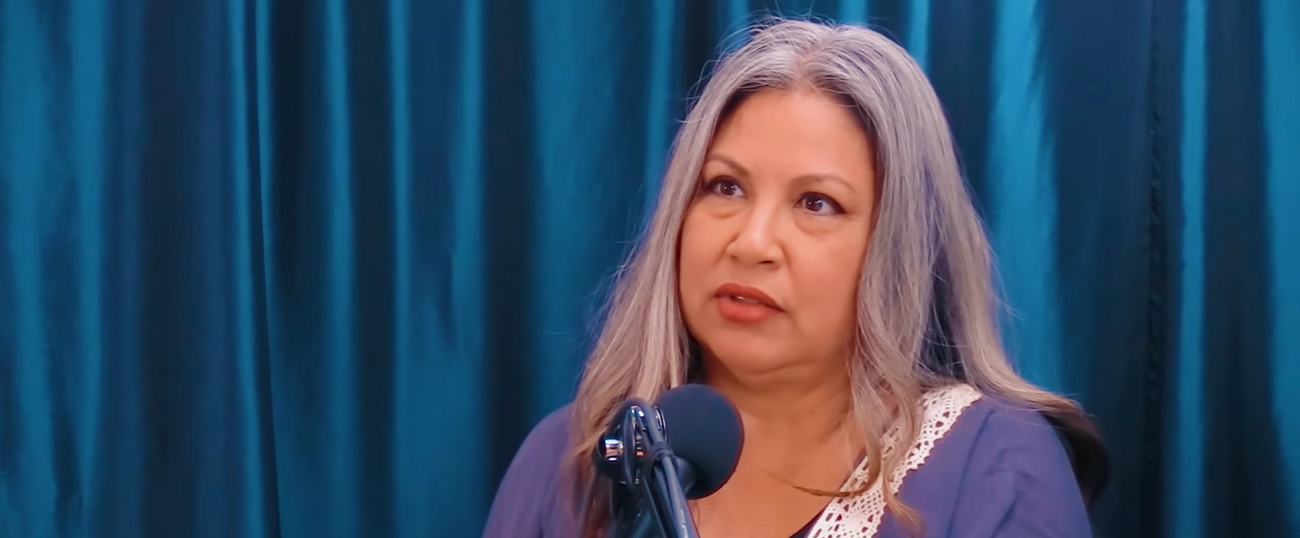

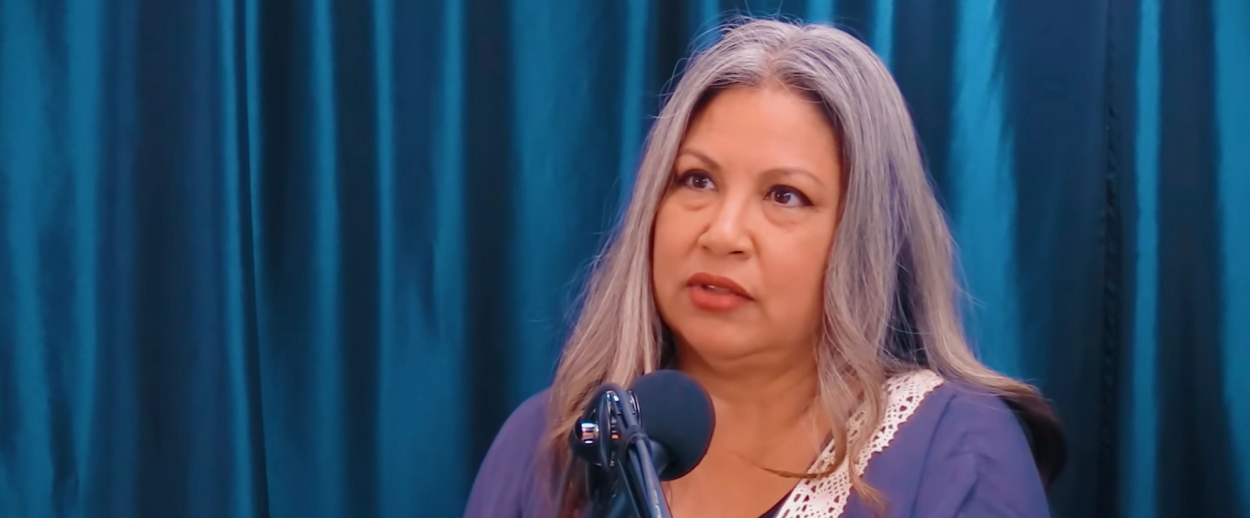

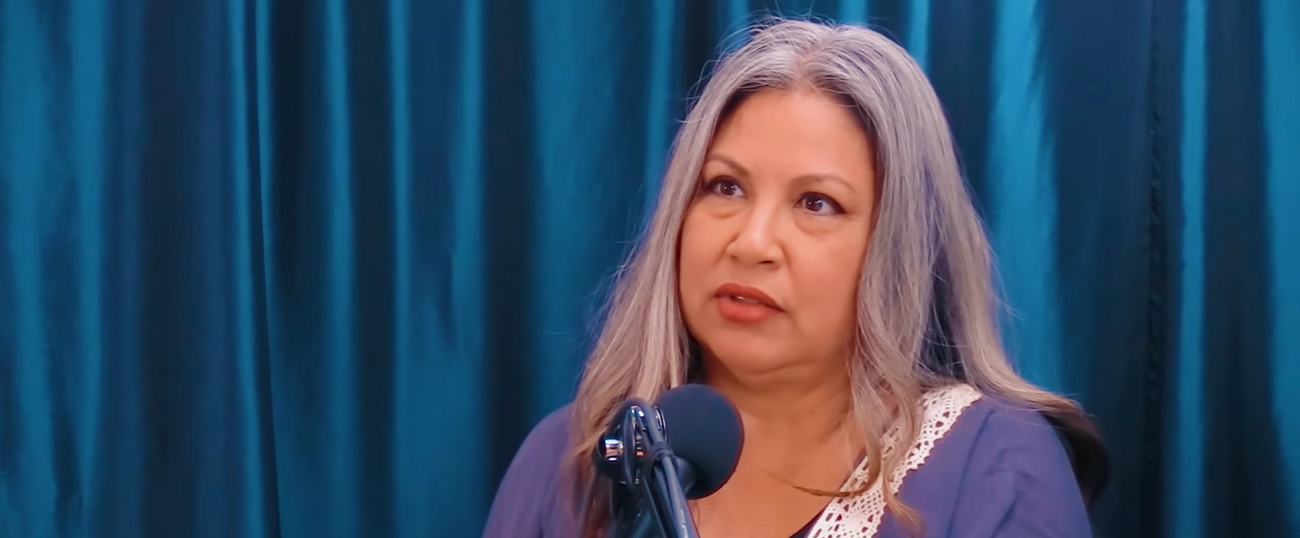

Maria Estrada is running as a progressive challenger to California State Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon in the state’s 63rd district. Endorsed by multiple local chapters of the Bernie Sanders-founded Our Revolution, she came in second in the June primary with 28 percent of the vote, assuring her a showdown with Rendon in the general. There’s just one small problem: Estrada is also an anti-Semite, and not a particularly subtle one.

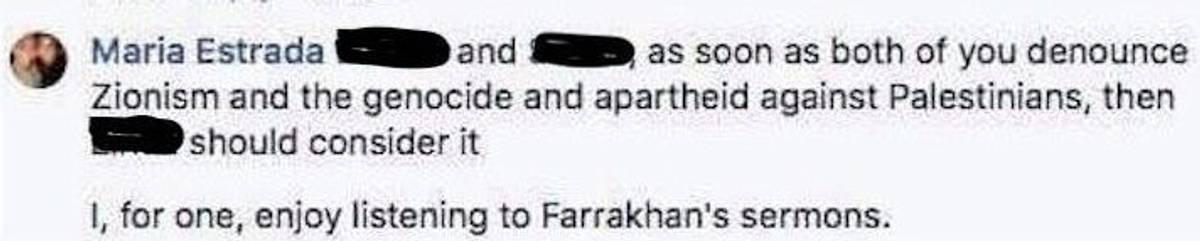

On social media, she has declared that, “I, for one, enjoy listening to Farrakhan’s sermons.” Louis Farrakhan, for those in need of a refresher, is the anti-Semitic and homophobic cult leader who has blamed Jews for everything from 9/11 to the slave trade. (In fact, while this article was being written, Estrada exhorted her Twitter followers to “listen to Louis Farrakhan.”) This past May, Estrada also attacked Eric Bauman, the chairman of the California Democratic Party, telling him to “try keeping your party, your religion and your people in check.” (Bauman is an openly gay Orthodox Jew.) She repeatedly accused Israel of committing Palestinian “genocide,” a blood libel on a national scale given that the Palestinian Bureau of Central Statistics records a four-fold increase in the Palestinian population since Israel’s founding.

Estrada’s particular brand of anti-Jewish invective highlights a challenge for progressives on anti-Semitism. To their credit, leftists find it easy to recognize and call out anti-Jewish bigotry when it appears on the right as undisguised Nazism, which is more than can be said of the president. But many progressives have trouble identifying and expunging such hate when it comes from one of their own and masquerades as “criticism of Israel.”

Indeed, when confronted with her history of anti-Semitic statements, Estrada knew exactly what to say. “To be clear, I am anti-Zionism, not anti-Semitic,” she told The Forward. Estrada did not explain how attacking California Jewish political figures over their religion or promoting Farrakhan were “anti-Zionist” positions. But she knew that by simply throwing Israel into the conversation and bashing it, she might be able to cash a “Get Out of Anti-Semitism Free” card among her compatriots. Similarly, after Women’s March organizer Tamika Mallory was exposed as a longtime promoter of Farrakhan and refused to repudiate him, she belatedly booked herself a trip to Israel and the West Bank with an anti-Israel group, in an effort to gloss over her promotion of an anti-Jewish preacher with some newfound anti-Zionism.

These efforts to disguise anti-Semitism as legitimate political discourse should not surprise. Anti-Jewish bigotry has always followed the path of least resistance in any community, dressing itself up in whatever guise that community considers respectable. As Berkeley’s David Schraub has written, “Anti-Semitism will always be expressed in the dominant language of the place and the time, and it is entirely predictable that people will seek to express anti-Semitism in ways that enhance rather than detract from their social standing.” Thus, in a deeply religious society like medieval Europe, anti-Semitism would be justified through theology, whereas in societies that esteemed science like Nazi Germany, anti-Semitism took on the imprimatur of “race science.” In both instances, the problem was not “religion” or “science,” but how these legitimate endeavors were appropriated and perverted by bigots to serve anti-Jewish ends.

Something similar, writes Schraub, is happening in progressive spaces today: The entirely legitimate enterprise of criticizing Israel is being used by anti-Semites to launder their hate. “Precisely because there are perfectly valid critiques of Israel that are, on their face, wholly laudable from within a progressive paradigm, a speaker harboring antipathy towards Jews and looking for a socially acceptable vector to express them will gravitate toward that issue.” In this manner, anti-Semitism is repackaged as “Israel criticism” in left-wing spaces.

Combating this dangerous dynamic is a challenge that progressives and the Democratic Party must meet. If both groups intend to be credible voices on anti-Semitism and on Israel, they’re going to need to learn to spot bad actors like Estrada who use Israel as an excuse for their unreconstructed Jew hatred. Identifying and casting out these bigots will not only marginalize the bigotry, but will also open up a constructive space for criticizing Israel that isn’t tainted by anti-Semitism.

Needless to say, Donald “Very Fine People” Trump and the Republican Party have not exactly passed this test with flying colors, and have repeatedly failed to ostracize bigots in their midst. Whether the chapters of Our Revolution that endorsed Estrada will do better remains to be seen.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.