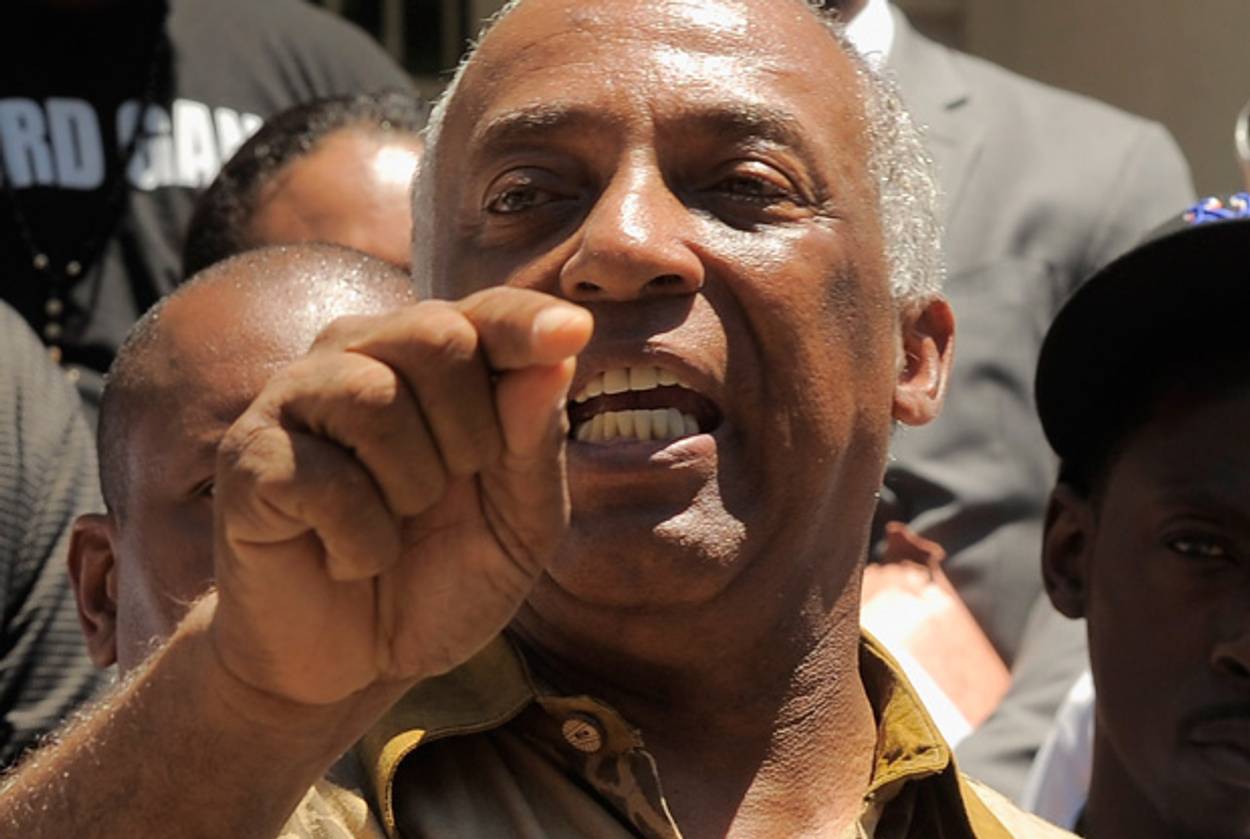

What We Can Learn From Charles Barron

Some thoughts on a strange candidate.

It’s election day, folks! Well, in Brooklyn, anyway, where Hakeem Jeffries is facing off against Charles Barron for the Democratic nomination, which likely determines the election itself. Why should you care? Well, as Michael Moynihan documented for Tablet a bit ago, Barron is a ludicrously-anti-Israel-bordering-on-anti-Semitic-pro-murderous-dictator-nutjob. So not your average race.

It’s a bit scary, but also incredibly revealing. Here’s three things – ranging from the mundanely political to the politically philosophical – that we can learn from the Jeffries-Barron race.

1) Barron is likely to lose.

There is real panic among Democratic leaders that Barron might win. As far as I can tell, the fear stems from an endorsement from the seat’s former holder Ed Towns, one New York Times article touting a “Barron surge,” and the simple fear created by the anticipation of a very bad outcome. It’s not clear how much the endorsement matters and the Times article is a bit short on evidence. That’s not me saying that – the Times’ own local blog is a bit perplexed:

The Times editorial page strongly endorsed Mr. Barron’s opponent, Assemblyman Hakeem Jeffries. And the next day, so did the conservative New York Post. So if the surge is happening, it’s hard to tell. Mr. Barron, of course, has raised virtually no money for his campaign against the relative Rockefeller, Mr. Jeffries, the Fort Greene lawmaker who announced last week that he captured more cash in the past quarter than at any other time in the race.

The money advantage is even bigger than you think, as Joe Coscarelli pointed out on Friday:

But as the Tuesday vote approaches, Barron has just about $6,000 left in his campaign piggy bank, compared to Jeffries with nearly $400,000, Capital New York reports. “Hakeem is going to win the race,” one local politician said. “Everyone feels that. But to have [Barron] even performing at this level is a little unnerving.”

And as far as endorsements go, Jeffries has Governor Andrew Cuomo, the most high profile local papers, several important unions, a raft of significant Democrats and democratic institutions, and a wink-wink-nudge-nudge photo-op with the President. Also, Jewish voters could be critical given the district’s demographics. Since there’s been virtually no polling done on the race, I think the evidence we have to go on suggests it’s Jeffries’ race to lose.

2) American liberals are not interested in a candidate like Barron.

When everyone from the Times editorial page to MoveOn.org to Governor Cuomo to Senator Chuck Schumer are intervening in a primary distinguished principally by Barron’s radicalism, this race is providing strong evidence that there’s no real organized constituency for someone with Barron’s views (more on what that means in Section 3). Of major non-KKK national groups, only the Sierra Club has endorsed Barron, and even that was a decision made by the local chapter based entirely on his work in green space in NYC and opposition to fracking. One more notch against the theory that the Democratic party is somehow hostile to Israel.

3) So-called foreign policy “leftism” isn’t a more authentically left position.

One of the main reasons MoveOn blasted Barron was that he opposed marriage equality, whereas Jeffries was a cosponsor of the legislation that legalized it in New York. This disrupts our conventional views of political alignment – hard-left critiques of Israel, embracing dictators as “African heroes,” and scathing broadsides against race relations in America are generally thought to be part of a certain “very left” package, which usually also includes more progressive views on gay rights.* While Barron is an extreme, nigh-parodic variant of this worldview who cannot be justly seen as a benchmark by which to judge it, he’s still identifiably of that tradition. So what’s up with Barron?

Nothing, actually – he’s just usefully pointing out that our current notion of what makes a position more left-wing is somewhat arbitrary. While there are some actual principled reasons why left-liberal views on economic and social rights should cotravel (namely, they’re tied together by a certain vision of social equality), there’s no similarly coherent reason why those views ought to be accompanied by a foreign policy outlook that focuses its critique on the actions of the US and its allies in most cases. There are strong left-liberal values that would require one to care about global poverty, but no equivalent that requires one to (for example) take one position or another on the root causes of terrorism or humanitarian military intervention.

I’d posit the difference between lefty camps here is empirical, not conceptual. Different factions disagree about how much the United States is responsible for the world’s ills; to what extent Israel can justly be blamed for the plight of the Palestinians, and so on. And that’s totally fine, but it’s not particularly coherent to pretend that one side or the other about an empirical debate is more authentically left-liberal in any principled sense. We should recognize that it’s no more left or liberal to condemn Israel as an apartheid state than it is to develop a somewhat tempered critique of the settlements.

Aha! You might say. He’s running together “left” and “liberal,” which are different things! It’s a fair point, and beyond the scope of this blog post to respond to in full. But, briefly put, I don’t think this maneuver can work. First, in American political discourse, we usually run “left” and “liberal” together, even though there’s a pretty robust tradition of left-wing critiques of liberalism and vice-versa. So even if all I’ve shown that it’s not more “liberal” or “left-liberal” to have a more radical position on US or Israeli foreign policy, that’s worth noting.

But, further, I’m not even sure the left/liberal maneuver is all that helpful in this case. Its only use might be attempting to pick out a set of left values, like anti-imperialism, that requires, say, opposition to American military preeminence. But what if another lefty disagrees that that the US can meaningfully be seen as an imperial power and invokes that other traditional left-wing value – solidarity – to suggest that the US has a duty to use its power to prevent genocide? This debate would hinge mostly on assessments on the empirical/historical record of American foreign policy and military intervention rather than principled grounds. Again, the major fault line here isn’t a principled one, so what makes one side more “left” than the other?

There’s probably a further point here about the so-called “decline of the Jewish left,” but I’ll leave that up to readers to puzzle out.

Oh and, uh, vote Jeffries today, Brooklynites!

*Or rejecting marriage altogether as a sexist, heteronormative institution, but that’s not the character of Barron’s opposition to marriage equality. In what’s classically a right-wing talking point, he dismisses equality as an imposition of “values” on his family.

Zack Beauchamp contributes to Andrew Sullivan’s “The Dish” at Newsweek and The Daily Beast. His Twitter feed is @zackbeauchamp.