What We Talk About When We Talk About Israel

When a bunch of psychoanalysts try talking about the Jewish state, they reveal a lot about their own repressed feelings

This past week, a petition was circulated on several psychoanalytic listservs to which I subscribe.

“We are writing,” it began, “to express our opposition to the recent decision by the Board of the IARPP to hold its 2019 international meeting in Israel, a decision made known by its outgoing president Dr. Chana Ullman. We respectfully request that the Board reconsider this decision.”

Normally, I wouldn’t pay such a note much mind. After all, groups, organizations, and celebrities announce, retract, or confirm their appearances in Israel every day, and one cannot be expected to get excited every time this particular—and particularly exhausting—ballet is played out. I resolved to keep out of it, but the posts continued, and their volume grew higher.

“Our opposition is rooted in the grave crisis posed by the Israeli occupation and its currently escalating attacks on the Palestinian people,” read one, “attacks reflective of an overarching policy of ethnic cleansing and consequent seizure of land, restriction of freedom of movement, and control over natural resources. The occupation has launched from the beginning a wholesale assault on human rights and human dignity.”

I gulped. My threshold for attack is high, but these words, and many more that followed, felt to me like a physical assault on my Jewishness. I could feel it registering in my chest and solar plexus. Still, having grown up on the sweet reasonableness Tom Ashbrook types who see both sides, I urged myself not to become a partisan but to remain what I was: a Psychoanalytic psychotherapist, a dispassionate outsider looking in.

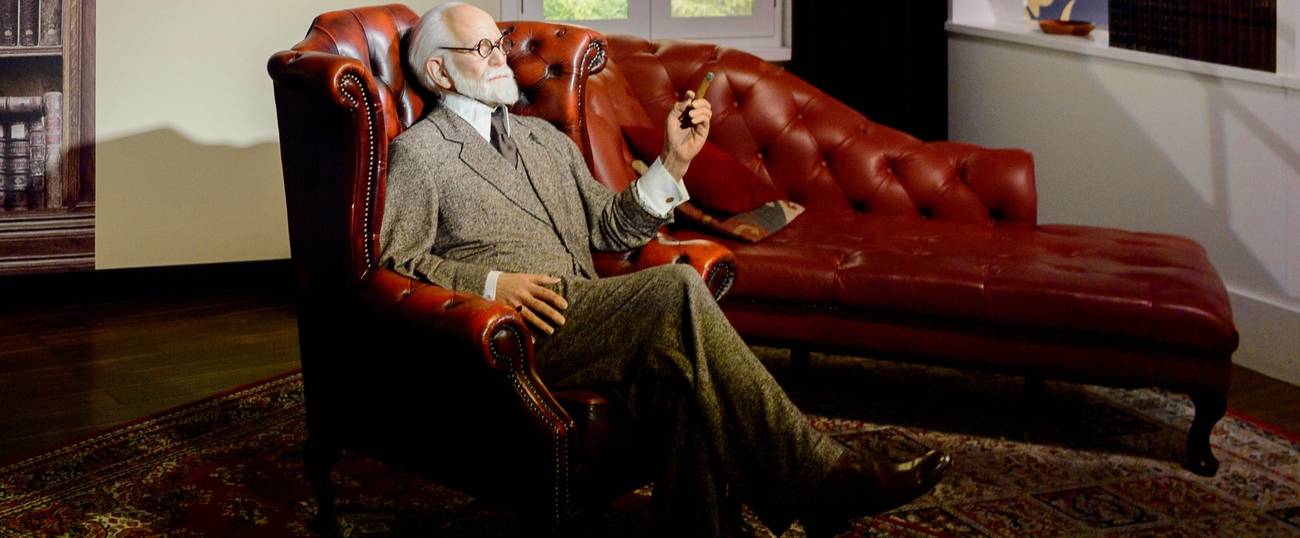

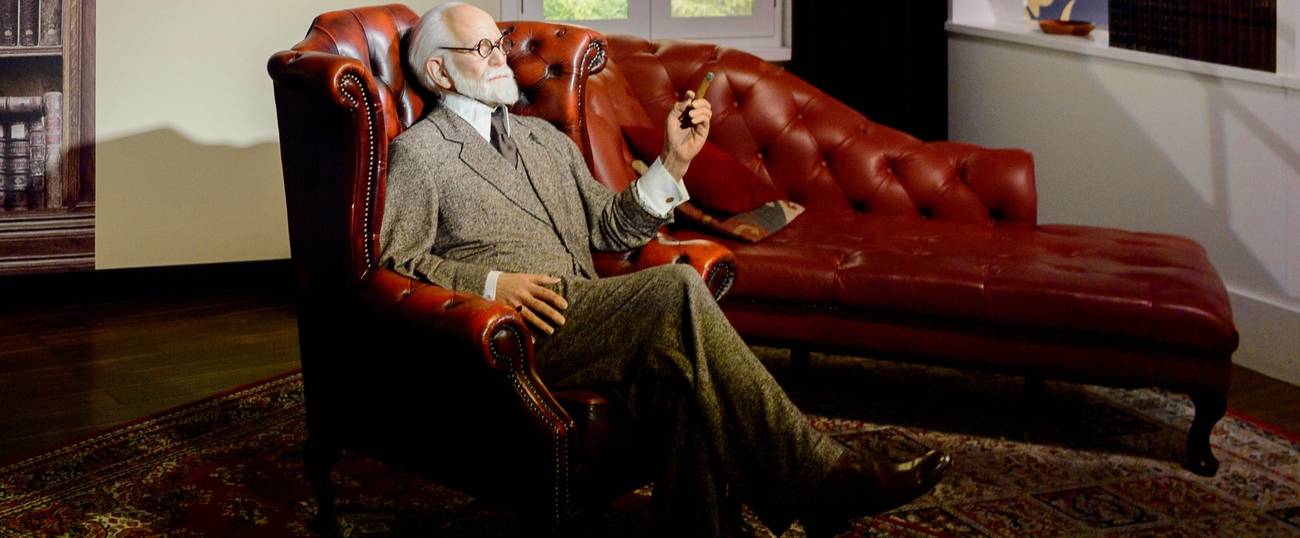

The posts continued at high decibel. This being a listserv for psychoanalysts—many of whom, you will not be surprised to learn, are Jewish—the Holocaust was evoked by both sides, and the language grew more and more loaded with each post. But when one colleague, an Israeli, asserted that the Jewish state itself is ill with a narcissistic disorder and needed to be rebuked, I realized that what I was reading wasn’t just another Israel-related quibble. It was the return of the repressed.

You hardly need to be a therapist—or in therapy—to recognize that the term is Dr. Freud’s. And few were the things the good doctor struggled with more mightily than his own Jewishness.

“In some place in my soul I am a fanatical Jew,” Freud wrote in 1935. “I am very much astonished to discover myself as such in spite of all my efforts to be unprejudiced and impartial. What I can do against it at my age?”

The answer, of course, was nothing at all, just as Freud’s followers, my colleagues on the listserv, could do little as their own fanatical feelings about being Jewish bulged from behind the veil. It was not quite governable.

Freud himself tried to account for the indirect way that Judaism (and presumably its binary twin anti-Judaism) keeps appearing. He described the immortality of the Jewish people, and found that “Jewishness” is something that is extremely difficult to completely repress or erase.

By way of inscrutable paradox, it is somehow particularly Jewish to repress or repudiate one’s Jewishness. Freud’s response was to found a secular, godless faith on the ruins of the old religion. Instead of wanting redemption by God, he thought we could redeem ourselves by knowing more—knowing what we did not want to know or what we couldn’t know about ourselves could save us.

The analyst/thinker Michael Eigen gave all these unknowns a helpful name. In every psychoanalytic session, he wrote, or even across a person’s life, there is a great non-event. This non-event is the un-heard scream which can be heard only through the most careful listening.

Thinking of my warring listserv, I wondered: What unheard scream might I strain to hear there? What heretofore unheard truth is struggling to come out?

Each of us might come up with their own answer, but I heard something and what I heard surprised me.

I had grown up steeped in Jewish learning, and I was under the impression that one is Jewish by how closely one adheres to the text and to the tradition. I knew this wasn’t really so, but I lived as if it was.

But now I started to re-consider what makes people Jewish.

Of course, us modern Jews are heirs to many, diverse traditions, many ways of connecting to our Judaism: Zionism, Bundism, Yiddishism, Hassidism—each offers us its own path. Yet what I saw on the listserv opened up the possibility that all of this diversity is still funneled through one high-pitched portal—something powerful, mysterious, un-nameable perhaps—that is nearly independent of doctrine. No matter what a person’s position was on the Israel quibble, they all seemed to see themselves as “protecting Israel,” as though they were protecting a part of themselves that needed protection: Their Jewishness, however they define it.

When a portion of the painful past “returns from oblivion,” Freud noted, it “asserts itself with peculiar force, exercises an incomparably powerful influence on people in the mass, and raises an irresistible claim to truth against which logical objections remain powerless.”

What is repressed will inevitably return, and not always for everyone’s good. If the return is inescapable, then perhaps our profession can help the return be for the good, but for that to happen we may first have to consider that Israel is perceived as something much more than a country. Rather, Israel seems to be a kind of tabernacle to hold or from which we withhold our convictions and our principles in a way that broad religion once did but no longer might.

But of course if “Tabernacle-Israel” is a fantasy, then what do we therapists do with our angel-heads, the parts of us that do our healing work so well, and yet also burn for a heavenly connection–and for perfect justice?

Israel is seen to possess either a snake-like brain, or the heart of a dove; it’s either portrayed as the devil or as an angel of God. But isn’t that the human predicament? This is the conflict in which we earth-bound therapists specialize. Psychoanalysis silences neither the dark nor the light in us. It certainly does not possess the truth, but it illuminates the truth best when it respects and allows itself to feel the deepest mysteries of love and faith.

It is possible then, that when we shout about Israel it might not always be about Israel, but rather in a sense, it may be about our conflicts and wishes that spring from the deepest, truest but least comprehensible place inside us.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.