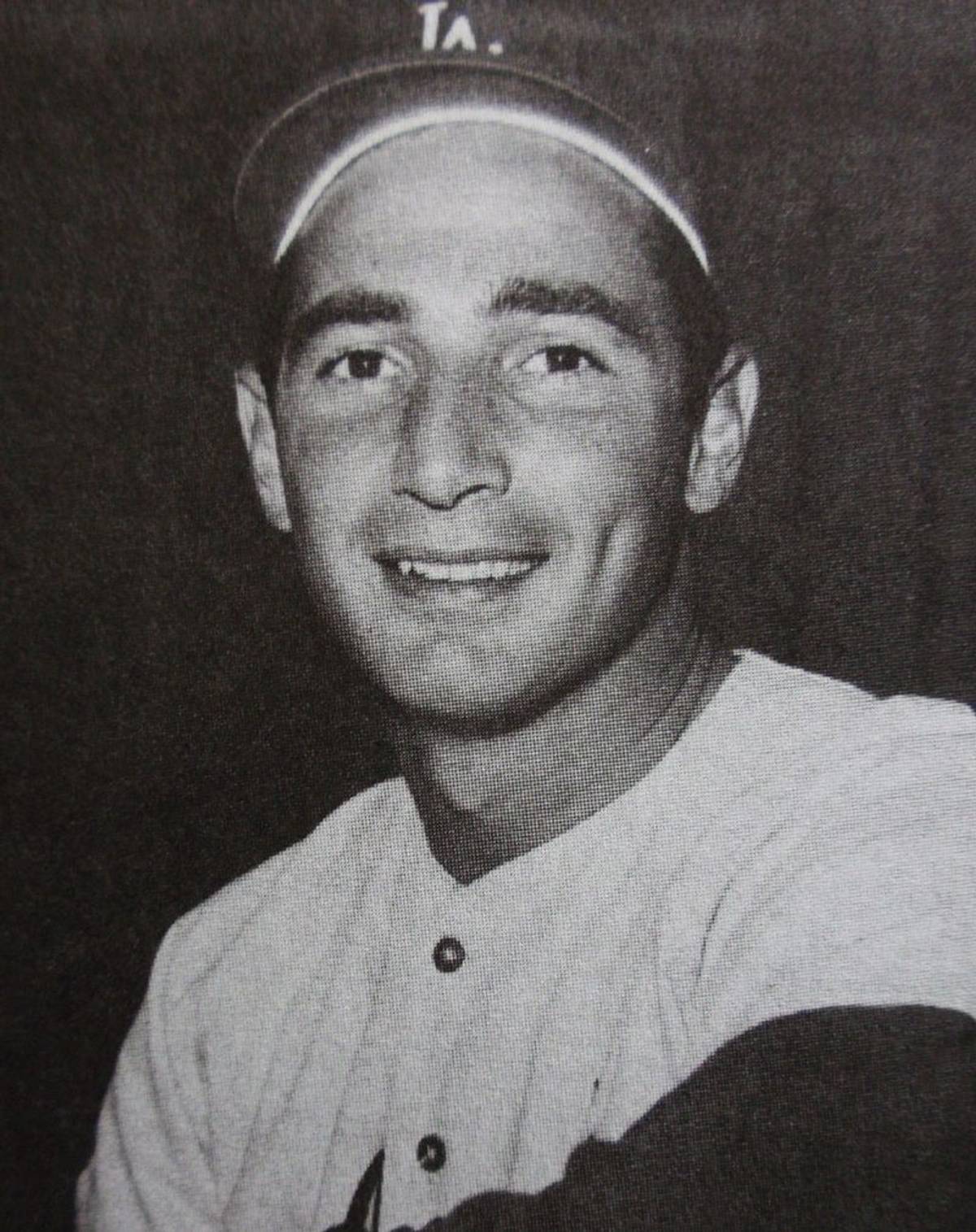

The 10-day period known as Yamim Noraim, or Days of Awe, in which we repent for our sins, often lines up with baseball’s ever-expanding postseason. At this time of year, many Jewish baseball fans (a Venn diagram that comes close to a circle) recall Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, who famously declined to pitch Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. More than a half-century later, his decision offers a never-ending source of nachas for American Jews, who saw in his stance the possibility of being proudly Jewish and proudly American, within the culturally essential confines of the national pastime. And because the World Series now occurs so late in October, Koufax likely will be the last Jewish player to miss a World Series game for Yom Kippur.

While Koufax was not especially observant, his Jewish identity was part of who he was as a baseball player, and he saw not pitching as an act of respect for his fellow Jews. Koufax’s decision has become integral to his legend, and it is a talking point in any discussion of Koufax as one of the greatest pitchers—Jewish and otherwise—of all time. This, in a way, adds to the legend of Koufax sitting, a watershed event in the Jewish-American experience.

The legend of Koufax’s stand has become so ingrained in Jewish-American culture that it has overshadowed the actions 31 years earlier, during Yamim Noraim 5695, of Hank Greenberg, then the first baseman for the Detroit Tigers. The High Holidays fell in early September 1934, with Greenberg’s Tigers looking to capture its first pennant since 1909. Greenberg played on Rosh Hashanah following much public debate and after receiving advice and guidance from rabbis across the country; one cited Talmudic references to children playing in the streets of Rome on holy days to conclude that Greenberg could “play,” but not work, that day. Greenberg attended synagogue in the morning, then hit two home runs in a 2-1 Tigers victory in the afternoon.

Nine days later, Greenberg did not play on Yom Kippur, recognizing it as the most sacred of holy days and a more solemn occasion than the joyous Rosh Hashanah. Greenberg again attended synagogue, where he received a standing ovation—he later described it as the one time in his playing career he believed he was a hero. Reported ESPN.com:

“The only way I would even think that I might have been a hero in those days was the day I walked in Shaarey Zedek Temple and got a standing ovation because I showed up in temple on Yom Kippur,” Greenberg said in 1984. “The poor rabbi standing on the podium ‘davening,’ praying, and suddenly I walk in and everybody in the congregation gets up and applauds. The poor rabbi looks around; he doesn’t know what is happening. And I’m embarrassed as can be, because it was all totally unexpected.”

Greenberg’s act of faith, which he’d repeat in 1938, even inspired a poem by Edgar Guest, which depicted two non-Jews discussing Greenberg; it closed with the following lines:

“We shall miss him in the infield and

shall miss him at the bat,

But he’s true to his religion—and I

honor him for that!”

As with Koufax three decades later, Greenberg’s decision demonstrated that it was possible to be both Jewish and American. Yet Greenberg’s stand has largely been lost to history, at least outside of Detroit. (In Detroit, any conversation about Koufax begins from the premise that he did the same thing that Greenberg had done three decades earlier). It is worth considering why the effect of one event is so much greater than the other, beyond the obvious fact that memories of events in 1965 resonate more than memories of events in 1934.

From a baseball standpoint, the difference perhaps makes sense. Missing a World Series game is a bigger deal than missing one of 154 regular-season games, even in the heat of a pennant race. Pitchers receive outsize attention, so Koufax not taking his regular turn is a more striking event, given that Greenberg played the day before and the day after the holiday.

The profile of each player also matters. Koufax is at least in the proverbial conversation for greatest pitcher of all time. In 1999, when ESPN produced a series on the top 50 athletes of the twentieth century, Koufax was the only pitcher on the list (a follow-up series added Walter Johnson and Bob Gibson). While great, and perhaps historically underrated, Greenberg is not the greatest first baseman of all time. Koufax was at the height of his athletic powers in 1965; 1934 was Greenberg’s second full season in the Major Leagues and while he had emerged as a star, he was not yet in Koufax’s light. The media environment also had changed. The World Series was a national event with national broadcast television coverage (in the days when that was all there was), with all eyes watching the World Series and seeing Koufax not pitching. There was no television in 1934, and broadcast radio was less than two decades old. Coverage was more local and in print—while Greenberg not playing was a big deal in Detroit, it did not resonate across the nation.

From the arc of the American-Jewish experience, however, Greenberg’s stand may have been more significant. This owes to the very different positions of Jews in American society in 1965 compared with 1934. To be sure, anti-Semitism existed in 1965. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 was still three years away from becoming law; housing deeds often contained “restrictive covenants” prohibiting sale to Jewish people and there remained many neighborhoods throughout the country where Jews could not buy or rent homes. The ‘60s remained a period in which LBJ could say, aloud (to Jewish Associate Justice Abe Fortas, no less), “I oughtn’t to have two Jews” on the Supreme Court. Many colleges, universities, businesses, and industries maintained informal quotas on Jews; soft “Gentlemen’s agreement” anti-Semitism remained, even if not as prevalent.

Yet Jews were thriving in the United States in this period. They had served in significant numbers during World War II, which provided greater entrée into the American social, educational, economic, and political fabric. The Baby Boomer children of those who served were attending college and graduate school and entering the professions in droves. Less the exotic other, Jews enjoyed greater opportunities for education, economic, and political power. By 1965, significant numbers of Jews, comfortable with their standing in America, were taking part in the Civil Rights Movement and working to establish and enhance the rights of African Americans.

Things looked quite different in 1934. The Jews who emigrated from Eastern Europe in large numbers beginning in the late 19th/early 20th century had been in the United States for less than 40 years. Many of the first-generation American Jews were still children, yet to seize on the educational and professional opportunities that awaited them and their children and grandchildren. It was the heart of the Great Depression and early in the New Deal, which FDR was implementing, in the face of skepticism and suspicion in many quarters, with the help of numerous Jewish advisers. Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany one year earlier and the Nuremberg Laws were less than a year away. In the United States, fascist, anti-Semitic, and white-supremacist groups, while not wielding formal political power, were part of the mainstream political conversation. Greenberg himself faced overt and aggressive anti-Semitism from fans and opposing players; it is said that only Jackie Robinson endured greater abuse. And Greenberg played in Detroit, home of Henry Ford and Father Coughlin, both of whom enjoyed access to significant media outlets and widespread followings for their anti-Semitic rants. In such an environment, Greenberg’s stance had special meaning for a group that was relatively new to the country and more on its margins.

None of this is to minimize Koufax or the stand he took. (According to Jane Leavy’s definitive Koufax biography, the lefty encountered anti-Semitism in his playing career, although more subtle and less overt and aggressive.) It is instead to call for not forgetting that Greenberg did the same thing in an even-more perilous time. His story remains as essential all these years later, a reminder to American Jews of our place and our history in the United States.