The Wicked Son

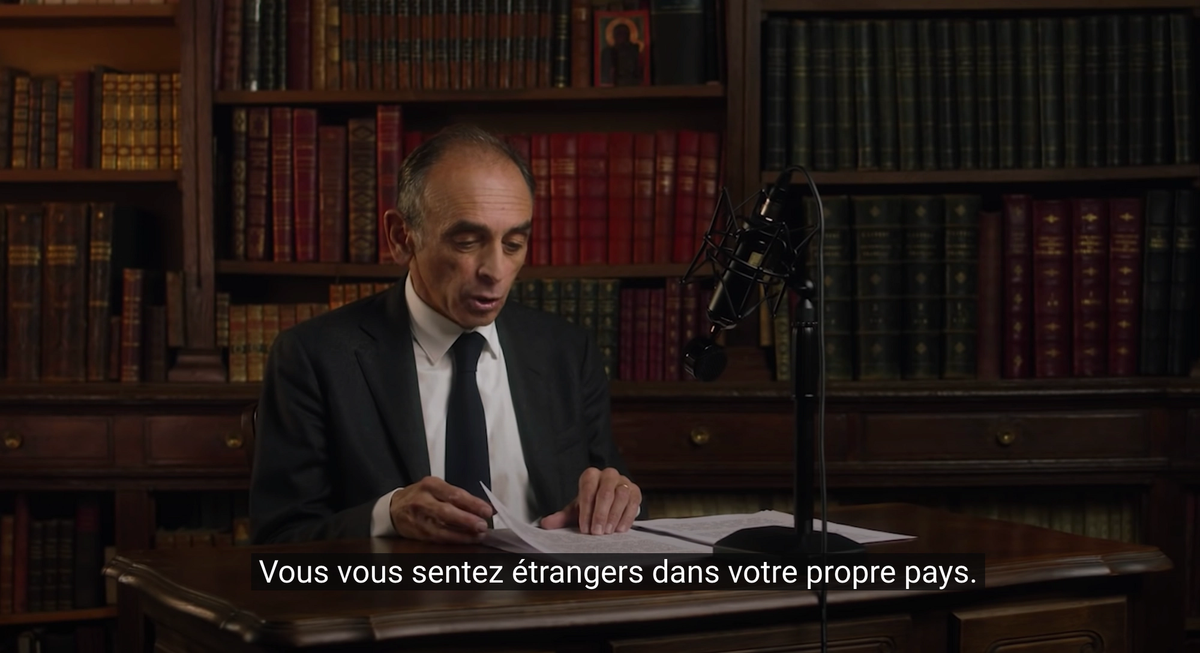

Will Eric Zemmour’s creepy misuses of his Jewishness help make him France’s next president?

In the fall of 2020, Eric Zemmour gave a strange history lesson to French voters. Comparing the situation of contemporary French Muslims with that of the Jews of the Emancipation era, he argued that the former should assimilate into French society the way the latter had done. Zemmour went on to assert that the Jews had fortunately abandoned the Talmud, which he called a political book, and returned to the Bible.

On hearing him speak, I felt like one of the stunned spectators of “Springtime for Hitler.” My jaw dropped. Samuel and Kings, less political than a Talmudic sugya on how to build an eruv? And who actually jettisoned the Talmud? Even the radical reformists did not, unless approaching the text critically amounts to getting rid of it—in which case they did the same with the Bible. Zemmour went on to mention as one of the founders of the “Aufklärung” (sic) “the musician Felix Mendelssohn.” Zemmour’s cursory reading of Wikipedia, combined with the power of his unconscious, had made him confuse the 19th-century Felix (who was baptized) with the actual founder of the Haskalah, his grandfather Moses.

While the Bible is not in any way an apolitical “book,” as Zemmour intimated, it can well be argued that, at least in the midst of Christendom, the Talmud did more to encapsulate the specificity of the Jewish mind, by laying out a specifically Jewish way of approaching the Bible. Even the wealth of Jewish opposition to the Talmud (that of the medieval Sephardic and Italian poets, of Provencal and Castilian mystics, of rationalistic interpreters of Scripture, and later of the Sabbataians) was often expressed in the very terms laid down by rabbinic discourse. By attacking this corpus, Zemmour symbolically lashed out at the possibility of a separate Jewish identity: a specifically Jewish way of being human, or, for that matter, French.

Zemmour’s widely known stance on the Vichy regime—which he falsely claims acted to protect rather than persecute Jews—can be explained, I propose, by this systematic rejection. Zemmour’s contempt for “Polish” Jews, for those foreigners or ex-foreigners whom the French authorities so unfairly betrayed, falls within the scope of his penchant for a sanitized, almost Protestant Jewishness—one with no territory, no language, yet also no strangeness, no exotic ritual, no ethical or prophetic message.

Some have argued that Zemmour’s rehabilitation of Marshal Pétain might also be typical of a certain Algerian Jewish ethos. Algerian Jews had been proud French citizens since 1870, beginning a long process of estrangement from their North African and sometimes Jewish roots—although many continued speaking Arabic until the independence of the country in 1962, while also keeping the religious traditions of their forefathers. Yet Zemmour’s take on Vichy is even more paradoxical when read against the backdrop of this peculiar history. Vichy was even harsher to Jews in Algeria than in metropolitan France, going as far as depriving them en masse of their French citizenship. Although no deportation occurred—probably thanks to the Allied invasion of November 1942—their marginalization there was particularly cruel, and many, like the philosopher Jacques Derrida, were to remember all their lives having been expelled from school. In Zemmour’s strangely postmodern narrative, this never happened either.

Zemmour’s relationship with his Algerian Jewish background may well account for his seemingly uprooted condition. Zemmour is a déraciné, to use a word popularized by the right-wing belle epoque author Maurice Barrès, a likely influence on his thought. Modernity, for Barrès, has displaced us. There is some truth to this judgment, and Zemmour is actually its living proof. While Algerian Jews no longer belonged to Africa or the Arab world, and their Jewish knowledge was often scarce, they never really made it in French society. Marginalized in 1940 after decades of humiliation—including pogroms—the vast majority still chose France in 1962, only to have their accent, their complexion, and their strange manners thrown back in their face. There is something deeply ironic about a discourse so focused on roots and authenticity from one who is himself déraciné. A perverted son of sorts, Zemmour admires what he imagines as the virile strength of those who oppressed his people, going as far as to call his political movement Reconquête, an allusion to the Spanish Reconquista that culminated in the Alhambra Decree of 1492, expelling Jews from Iberia. “Napoleon is my grandfather, and Joan of Arc my grandmother,” Zemmour once tweeted. In other words, he is an orphan.

A perverted son of sorts, Zemmour admires what he imagines as the virile strength of those who oppressed his people.

In the world of Paris journalists, Zemmour once passed as “religious.” Judaism being an utter mystery to these people, it is enough for a (Sephardic) Jew to eat couscous on Friday night with his family, or to refrain from consuming pork, to be seen as “religious,” especially if, like Zemmour, he attended Jewish day school during his childhood. Asked about his practice, the polemicist and now presidential candidate recently reassured his right-wing audience. No, I am not religious, he said soothingly—but what he likes about religion, especially Jewish religion, is that it contributes to maintaining family order and tradition. Zemmour needs tradition, since for him tradition equals authority.

Interestingly enough, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the far-left leader, was asked if Zemmour was antisemitic. He replied that this would be absurd, given that Zemmour is Jewish. But Mélenchon went further, arguing that Zemmour’s racism was itself particularly Jewish, since Judaism is all about protecting oneself from external influences. Mélenchon’s answer was insane, but it did somehow echo Zemmour’s own vision of Judaism, except that, to Zemmour, France is more important than his Jewish identity, and thus more worthy of being “protected.”

Zemmour’s ideology is the right-wing version of identity politics, in which identity is a gated and locked house, not a window onto the world. For many of his supporters, Zemmour provides a response to “la France moche,” the ugly “peripheral” France that is in need of roots and transcendence. They see him as immensely educated, and traditional education does matter in their eyes. France is decadent, they believe, but Zemmour’s taste for things past will save her.

Zemmour is no Donald Trump. There is no French Trump, for that matter, because French conservatives tend to style themselves as having a refined and sophisticated connection to the beauty of the French landscape, the glory of French history, and the elegance of French grammar. No French conservative would proudly butcher his language the way Trump does his. After decades of living in the shadow of liberal and Marxist hegemony, in fact, such conservatives now occupy the most fashionable corner of the intellectual scene, and Zemmour has done all he can to pass, first and foremost, as an intellectual. That he is really a product of mass media, that his diction is poor, and his culture fake (in these ways, perhaps, he is much like Trump) does not prevent some genuinely conservative French citizens from reading a classical grandeur into his candidacy. I can sympathize with this kind of nostalgia—a very European phenomenon that has little in common with the conservative American variety, as even European Liberals and Socialists tend to feel it in their old-world kishkes. But Zemmour’s France is nonetheless a kitschy vignette, devoid of any actual grandeur. In reality, he is not a believer in much besides power.

Louis XIV’s France was great because that king fancied himself, even when sinning, as a messianic messenger of God. So too were, in their own way, the Third Republic and the Resistance. Zemmour contradicts himself by asserting, on the one hand, that France has always been great, and on the other, that loving her must include love for her flaws and crimes. Thus Zemmour is actually unable to see his beloved country as something other than the sum of the facts that make up her history. A true patriot would see that Pétain signifies something true about France in the same way that King Ahab signifies something of Ancient Israel. Do Jews not commemorate the sins of their ancestors while (ideally) attempting to transcend them through piety, study, and the quest for justice? In the case of France, the attempt must be made to use her élan, her musketeer spirit to overcome her cowardice and pettiness—an impossible feat unless virtues and vices alike are considered honestly.

Zemmour’s world, by contrast, is as flat as that of the atheistic far left he castigates. Man, as Zemmour sees him, is only power and self-interest; even beauty serves the sole purpose of political glory. (Zemmour celebrated his 50th birthday, it should be noted, at the Château de Malmaison.) In many respects, he and his Jewish aides resemble the Jewish Bolsheviks of old (or the woke Jews of today). They too believed in power. They too submerged their Jewish identity on behalf of something larger—the proletariat, the people, justice, Russia. In the same way as Zemmour’s Jewish advisers reportedly like to joke around about their Jewishness at every opportunity, one can picture Bolsheviks from Odessa teasing their Volhynian comrades. Theirs was a mechanistic world, with no meaning other than conquest and brutality. Zemmour is less brutal, but his anthropology is akin to theirs. And so is his Jewishness.

Zemmour suggested in September 2020 that Alfred Dreyfus was in fact guilty. This is not only offensive to the memory of that innocent man, which, in a way, does not matter. More importantly, the presidential candidate and national media sensation approaches the Dreyfus affair like a parvenu of the mind.

For “l’Affaire,” as Charles Péguy said, was a mystical moment. Péguy was, paradoxically enough, both a socialist and a conservative. Dreyfus had put him on the path of Jesus. Péguy’s name, it should be recalled, appears at the war memorial, rue de la Victoire, in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue of Paris, among those of the French Jews killed during the First World War. “I wish that my husband’s name, CHARLES PEGUY, be joined with those of the Jews who, like him, gave their life for France,” wrote the writer’s widow. As a teenager, I would attend the Yamim Noraim services there, and this Catholic name fraternally accompanying thousands of Jewish ones always moved me to tears. Péguy saw himself as kin to that prophetic nation, the Jewish people, both as a Catholic and as a French patriot. An entire French Jewish mystique is mixed up in the name of Dreyfus.

Zemmour sometimes refers to Péguy, clearly without understanding what he is saying. In any case, he may have believed that an infantile prank like slandering Dreyfus might successfully lure some half-educated, Ann Coulter-like pundits. But this attitude of his is at least proof that he does not know what it is to be a French Jew, and can’t speak on that community with anything resembling authority.

In spite of all his pathetic efforts, Zemmour is no “Israélite français”—the term that prewar French Jews preferred for themselves. When referring to the ethical duties of Judaism and their defilement in the person of Zemmour, Bernard-Henri Lévy acted like one of those 19th- and 20th-century French Jews, for whom justice was the key principle of the faith. Zemmour absurdly called his foe’s attitude “communautarisme le plus infect,” or the most revolting communitarianism, as if invoking Deuteronomy and the Prophets on behalf of humanity is less universalistic than defending Pétain or closing French borders to Afghan women. For all their patriotism, the belle epoque Israélites fought for Dreyfus and his memory—not despite but because of their patriotism. As French Jews, they would pray on Shabbat (as their descendants and spiritual successors still do) for God to protect “France, cradle of human rights” and to inspire her to “fight for right and justice in every place.” By doing so, they were acting as the actual heirs of the Bible and as grateful sons of France at the same time.

The specific type of self-hatred that Zemmour expresses is not a purely ideological trait. He craves the acceptance of the well-heeled. Arthur Szyk’s “wicked son,” in his famous rendition of the Haggadah, is not any modern-day, BDS, keffiah-wearing, self-hating Jew. He is something even more pathetic, a ludicrous stag-hunting Londoner who believes that, because his son finally made it to Oxford, they will reek less of schmaltz in the refined nostrils of their Mayfair neighbors. Zemmour is the original kind of self-hating Jew, the parvenu who wishes he had a wedding in Notre-Dame de Paris or St Paul’s Cathedral.

To betray Judaism—the original religion of justice—on behalf of a modern conception of “justice” that involves harming your own people is certainly despicable. To forsake Judaism’s hoary rituals in favor of sappy New Age ceremony is certainly a sad thing to do. But what about the conservative who immolates his dead on the altar of assimilation? Zemmour’s stance is emblematic of our era, one of immature, “self-begotten” brats who deconstruct without ever knowing how to build. To be Jewish and disown the Talmud, and one’s own dead, as well as the values of the Prophets, while at the same time celebrating Christmas, as Zemmour proudly does? No thank you.

The Zemmourian right justly laments our modern hatred for “essentialism” and common sense. Things and beings do have an essence. Facts do matter. But those who praise Nazi collaborators and Resistance fighters in equal measure renounce common sense—and desecrate the simple good heartedness of the thousands of peasants, workers, and nuns, who risked their lives to hide Jews. The postmodernist bullshit and disregard for facts and elementary values that Zemmour (rightly) criticizes as a conservative, he also endorses.

For his speech announcing his presidential candidacy, Zemmour posed under a cheap replica of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa—another postmodern flourish. Polish nationalists were thrilled. What struck me was that, over two centuries ago, this venerated icon held a special sway over another Jew—one who, like Zemmour, advocated Jewish territorialism and assimilation, albeit with a redeeming quality that would be utterly foreign to the French provocateur. This was a Jew who was also fascinated by weapons, uniforms, and political vainglory, one who “will always be remembered,” as Gershom Scholem put it, “as one of the most frightening phenomena in the whole of Jewish history.” Jacob Frank was detained in Częstochowa from 1760 to 1772, after the Polish authorities discovered that his conversion to Catholicism was not sincere. There he was enthralled by the same Black Madonna icon, which he came to interpret in kabbalistic terms. In his opinion, the Shekhinah, the female aspect of God, was partially embodied in it. He believed that his own daughter would take this process of incarnation to its final stage.

To be sure, Frank’s kabbalistic feminism escapes Zemmour, who is certainly unaware of the icon’s Frankist history. Yet by choosing it for the very moment when he thought he was symbolically renouncing his Jewish belonging, he unintentionally reconnected with it in a paradoxical, atrocious, and fascinating way.

David Haziza received his Ph.D. from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. His research focuses on the crossroads of French literature and Jewish thought.