The Winner in Ukraine Won’t Be Russia or America. It Will Be China.

A seat at the European table won’t be too much to ask for the man who saves Europe from nuclear war

In addition to the crimes, the heroism, and the heavy toll in blood, the struggle for Ukraine may also come to represent one of the most strategically significant events of this century, or any other—the one that established China, not America or Russia, as the dominant power in Europe.

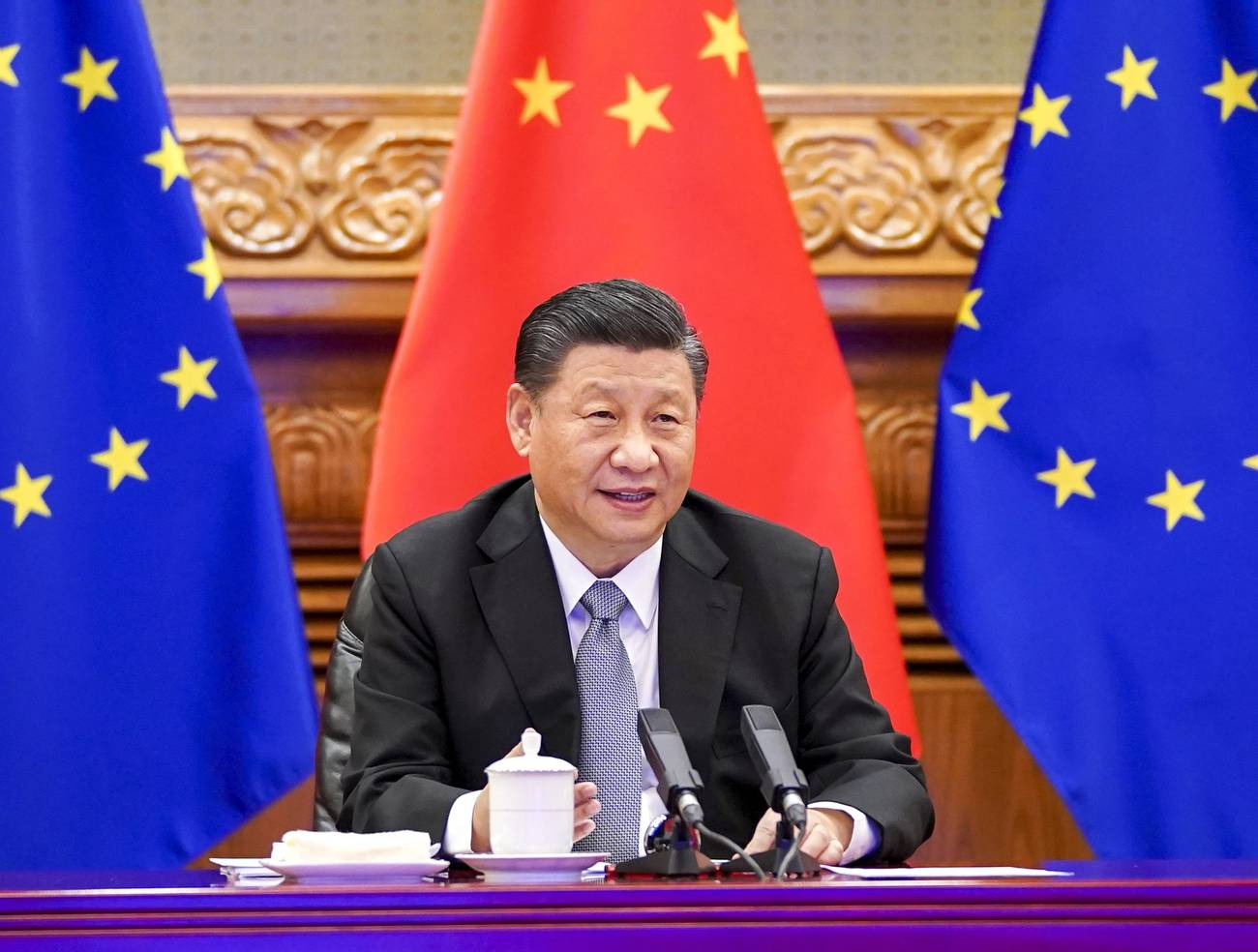

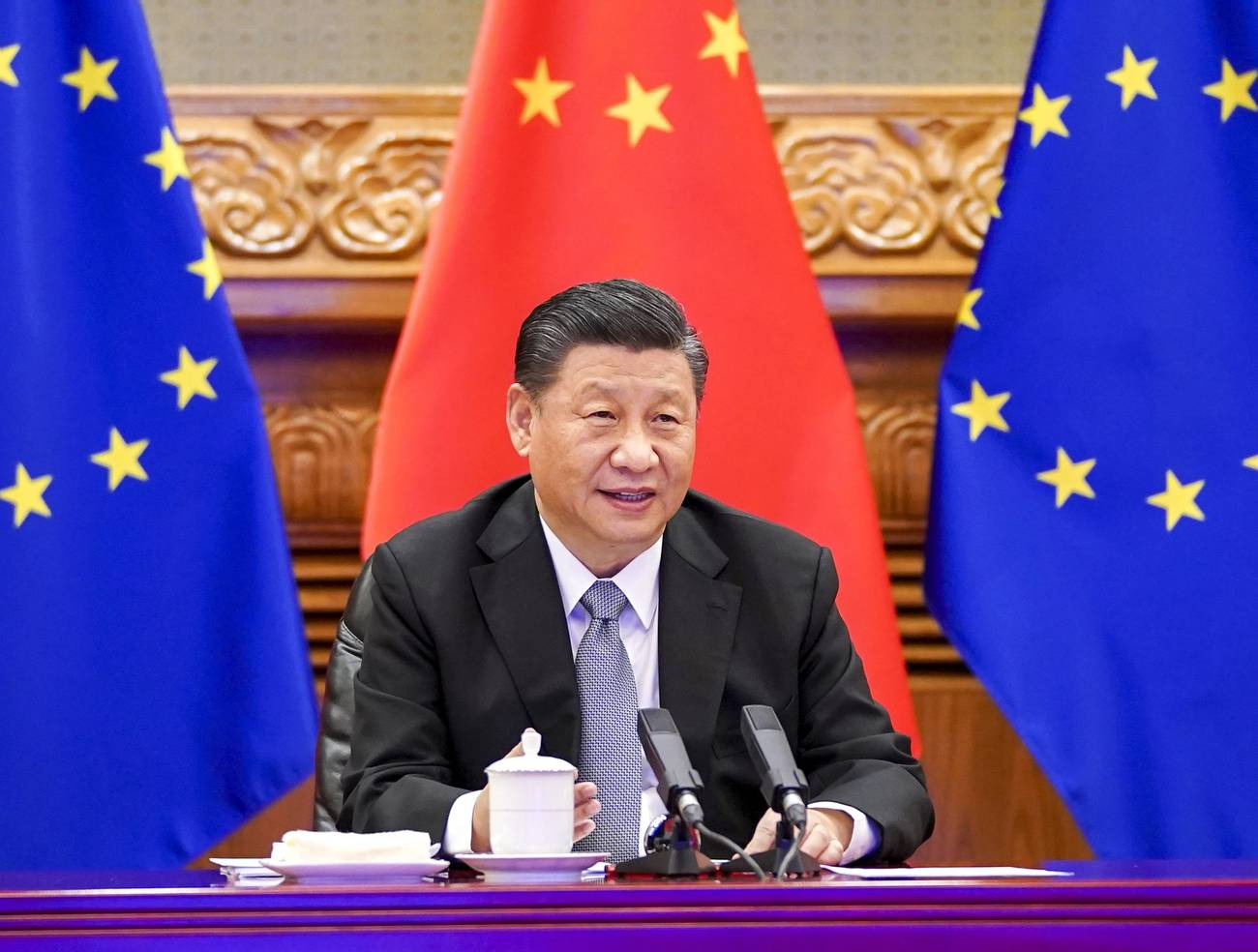

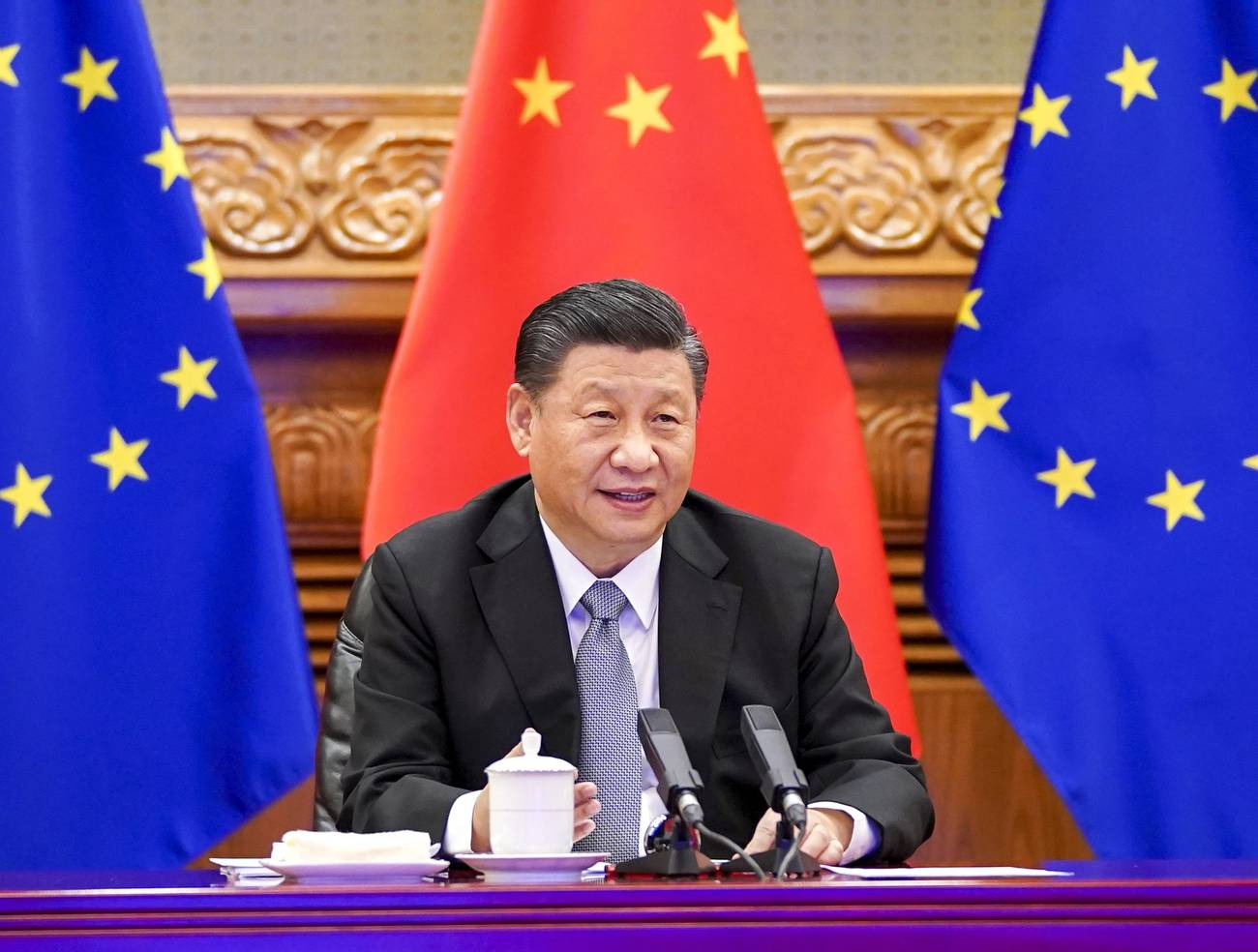

Most Western observers have taken Beijing’s professed readiness “to play a constructive role to facilitate dialogue for peace” as a sign that Ukraine is somewhere between a headache and a disaster for Xi Jinping, who announced a Sino-Russian partnership with “no limits” at the Beijing Olympics only last month. The assumption is that Xi is now in danger of looking complicit or credulous (or both), and that the Communist Party—having argued incessantly for the sanctity of China’s own territorial integrity—may now stand accused of hypocrisy. Xi’s support of Putin is also seen as having put Beijing at risk of igniting anti-Chinese sentiment in Europe, of squandering the many investments it made and trade relationships it built in the European Union, and of pushing otherwise friendly EU capitals closer to Washington.

Triangulation between Russia and Europe will no doubt require a degree of finesse for which China’s Wolf Warriors are ill-prepared, and providing Putin with liquidity to fund his war machine, for example, is not a cost-free decision. But anyone taking pleasure in China’s supposed bind probably has it backwards. In the wake of its partial expulsion from the global trade and financial system, Russia—with its vast supply of raw materials—is likely to become a Chinese economic dependency. That is a good thing for China, and if Xi can successfully position himself as the only world leader capable of restraining Putin, it will go a long way toward extending his hegemony all the way to Lisbon, as China starts to displace the United States as Europe’s most important global partner.

After all, would a seat at the European table really be too much to ask for the man who saves Europe from nuclear war? Reading the recent statement from the Chinese Foreign Ministry that promised “China’s mediation efforts for a ceasefire” in Ukraine, and the EU foreign policy chief’s concurrence that the broker of peace “must be China,” it’s not hard to see the request being made, and being answered in the affirmative—with Washington reduced to second fiddle on a continent it spent the better part of a century defending and holding together.

The last decade of Europe’s China policy has been schizophrenic, but on the whole, Xi has good reason to think that Europeans might prove receptive to his blandishments. Ever since China started sinking its neighbors’ vessels, sailing warships through international waters, flying sorties across the Taiwan Strait, committing genocide against ethnic and religious minorities, smashing freedoms in Hong Kong, and eliminating term limits for its “president for life,” the sum total of the European Union’s response has been a miscarried investment deal and a suite of nonbinding policy instruments designed to give the appearance of concern about Chinese economic penetration. European willingness to overlook Chinese complicity in human rights abuses and other transgressions has long been based on structural weaknesses and economic incentives that might only grow with the loss of Russian trade, the struggle to recover from a pandemic-induced economic contraction, and the return of large-scale war on the continent. A shift away from Russian gas toward renewable, nonnuclear sources of energy would require even more dependence on China, which is by far the leading supplier of solar panels, lithium batteries, and various rare earth metals on which “green technology” depends.

In the absence of a widespread consensus on China, the EU’s policy in particular has for years been limited to serving as a tool for obtaining commercial contracts, making Europe an ideal target for a Chinese strategy that uses trade and investment to ensure economic and political dominance and collapse American security networks that don’t serve its interests. Five years of solemn EU debate about Europe’s need for “strategic autonomy,” for example, culminated in a prosaic, German-driven investment agreement with China that didn’t advance any European strategic priorities, other than to sweeten market access for a handful of blue chip firms.

While the 2020 Comprehensive Agreement on Investment was put on ice last spring by the European Parliament after China sanctioned a number of EU committees, think tanks, and academics, a revival of some version of it—perhaps with a broader set of European corporate beneficiaries—may be part of the price that Beijing exacts for “restraining” its Russian client from waging total war in Ukraine or beyond. A successful EU-China deal would in turn complement Brussels’ new and long-awaited Indo-Pacific strategy, which turns out to be little more than a scheme for maintaining European supply chain stability; the Global Gateway, a hypothetical European Belt and Road competitor that includes no new funding and which one EU official called “nothing more than a letter of intent”; and the EU connectivity initiative, which some in Brussels consider “a use of EU taxpayer money to further Beijing’s BRI ambitions in its zones of interest,” according to one knowledgeable insider.

In addition to its institutional weaknesses, the EU has also been a soft target for Chinese influence and coercion in recent years because of its dependence on the plurality of political and economic power that sits in Berlin, whose own China strategy has been accurately summarized as “What’s good for Volkswagen is good for Europe.” When Angela Merkel became chancellor in 2005, China accounted for less than 3% of German exports; by 2020, it surpassed the United States as Germany’s largest trading partner. China’s share of German exports tripled during Merkel’s tenure, and Germany now accounts for 50% of all EU exports to China. In the past decade alone, fully two-thirds of total German GDP growth has come from exports; today they account for nearly half of its GDP. Crucially, exports support about 7 million German jobs, according to an estimate from the European Commission.

In public and especially in private, German officials have sometimes argued—often convincingly—that what might appear like the ruthless pursuit of German economic interests in China has always in fact been a deadly serious strategy for stability. According to many German elites, it is their duty to stave off the mass losses in manufacturing and economic dislocation that have rocked other advanced economies in recent decades, because the kind of economically driven populism that led to Brexit and the election of Donald Trump must be avoided in Germany at all costs. As the engine of German growth and Germany’s biggest trading partner, China is not just a large and enticing market—it is a hedge, German officials are not above implying, against the return of German nationalism.

If Germany’s Russia policy has been driven in part by convenience, in part by guilt, and in part by lucrative bribes, its China policy has always been driven by corporate profits. (With China accounting for only about 9% of total German goods exports, it’s hard to believe the insistence that trade with China sustains the high German wages that come from the export of manufactured products.) In the wake of Russia’s bloody war in Ukraine, and the accompanying embarrassment for Berlin, subsuming relations with Russia into a larger framework of economic ties with China is likely to prove convenient for all sides—and to further strengthen Berlin’s ties with Beijing. While the United States remains stuck in a rhetorically fierce but militarily toothless anti-Russia policy, Germany can expand trade with China, and through China with Russia, while giving the appearance of straddling the global U.S.-China divide, in a more lucrative 21st-century version of the country’s familiar Ostpolitik.

Berlin’s approach to China may make some sense for Germans, but it has never made sense for the EU as a whole. As in the case of the bloc’s sovereign debt crisis and its monetary and energy policies, however, no countervailing bloc has ever been able to mount an effective challenge to German preferences. Paris, keen to disguise German economic supremacy as a Franco-German partnership, typically avoids open spats with Berlin, including over China policy. Countries like Italy, Austria, Spain, Portugal, and Greece tend to follow the German lead (or in the case of Hungary, to run ahead of it).

The EU members of Northern and Eastern Europe have historically worried most about Russia, and therefore placed greater value on relations with the United States and NATO. But their hopes that greater alignment with U.S. China policy might buy them greater protection from Russia have now, of course, been dashed. If Washington won’t allow NATO to transfer Polish MiGs to Ukraine, the chances that it will send its own fighter planes or Patriot missiles to shoot down Russian jets over Riga or even Warsaw must be reckoned as low.

So where is resistance to Chinese overtures for diplomatic predominance over the Ukraine crisis going to come from? Probably not from Germany, which recently authorized a major Chinese acquisition in the Port of Hamburg, where Chancellor Olaf Scholz cut his teeth as mayor. Not from France, which has inked at least $45 billion worth of Chinese deals since 2019, including $15 billion for national champion Airbus to supply China with 300 jets. Not from smaller countries like Hungary, which hides Chinese infrastructure investment from Brussels by using shell companies that borrow from Chinese lenders, or Greece, which has given China a 35-year lease on Europe’s largest sea port. EU elites in general have been happy to watch the continent’s technology, design, production, revenues, and profits shift significantly to China—just as American elites have been made incredibly wealthy and satisfied by their own 20-year offshoring orgy.

If the answer isn’t Washington, then Beijing is the only other game in town.

In reality, Europe is a fragmented continent increasingly distrustful of the reliability and sanity of the United States, unhappily but helplessly dependent on German economic interests, destabilized by serial crises, eager to diversify away from fossil fuels, and terrified by the return of Russian imperial power and the prospect of a nuclear exchange. Far from being strategically autonomous, Europe needs a partner and protector. And if the answer isn’t Washington, then Beijing is the only other game in town.

Another reality is that America’s own China policy, insofar as one exists, has been a model of insincerity. In the course of haranguing EU officials and European capitals to reduce ties with Beijing, Washington has overseen a stampede of U.S. business into China, including in regions distinguished for the widespread use of slave labor and internment camps. Nor has the Biden administration’s yearlong quest to form a strategic partnership with Europe against China found much success. The president’s Marvel-like calls for a trans-Atlantic “alliance of values” to fight “global autocracy” fell flat in Europe over the past year as he imposed a nonsensical pandemic travel ban on EU citizens, bungled a withdrawal from Afghanistan that wasn’t coordinated with NATO, announced a trilateral security pact with Australia and the United Kingdom at the expense of France, and left Lithuania twisting in the wind after it confronted China over recognition of Taiwan with American encouragement. Why align with an erratic, hypocritical power that doesn’t hesitate to stab its friends in the back?

Putin’s war in Ukraine has done little to make Washington appear any more sincere or reliable even to its most ardent allies in Europe. To date, the White House is reportedly obstructing the transfer of combat aircraft to Ukraine via NATO’s eastern flank, refusing to transfer air defense systems or other weapons that might give the Ukrainians a fighting chance, and distancing itself more generally from military aid provided to Ukraine by Poland—all while working hand-in-glove with the Kremlin to conclude a nuclear deal with Iran on terms that might allow Russia to further augment its power in the Middle East. It’s hard to imagine why, when push comes to shove, even those European states and leaders inclined toward familiar American security arrangements would trust Washington to protect them from the slavering wolf on their doorstep.

If all this sounds like a catastrophe for Xi Jinping, rather than a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, he has a highway in Montenegro to sell you.

Jeremy Stern is deputy editor of Tablet Magazine.