Woke Inc.

A seemingly socially conscious corporate America is not a new phenomenon. It’s a revival of an old one.

To those who know American political history, the emergence of the woke-seeming American corporate sector is not surprising. These developments represent a reversion to the historical norm.

A few decades ago, free trade and mass immigration were championed by the business wing of the Republican Party and viewed with skepticism by the Democratic Party’s labor wing, based in the Midwestern factory belt. Today self-described leftists demand open borders and the free flow of transnational capital and labor alongside Koch-funded libertarians, while former liberal Democratic positions like those of Dick Gephardt on trade and Barbara Jordan on immigration are now considered right wing. In the past decade, numerous mega-corporations and Wall Street investment banks, abandoning neutrality in the culture wars, have used boycotts to punish state and local governments whose policies on civil rights and gender identity differ from those of the political left—just as they now proudly festoon their corporate websites with the logo of Black Lives Matter.

How did American corporations become such vocal bastions of ostensible leftism? The question betrays a misunderstanding of U.S. history, in which the Gilded Age lasted until the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, when top-hatted robber barons were at last deposed. But this confuses two distinct historical stages in the development of American capitalism:

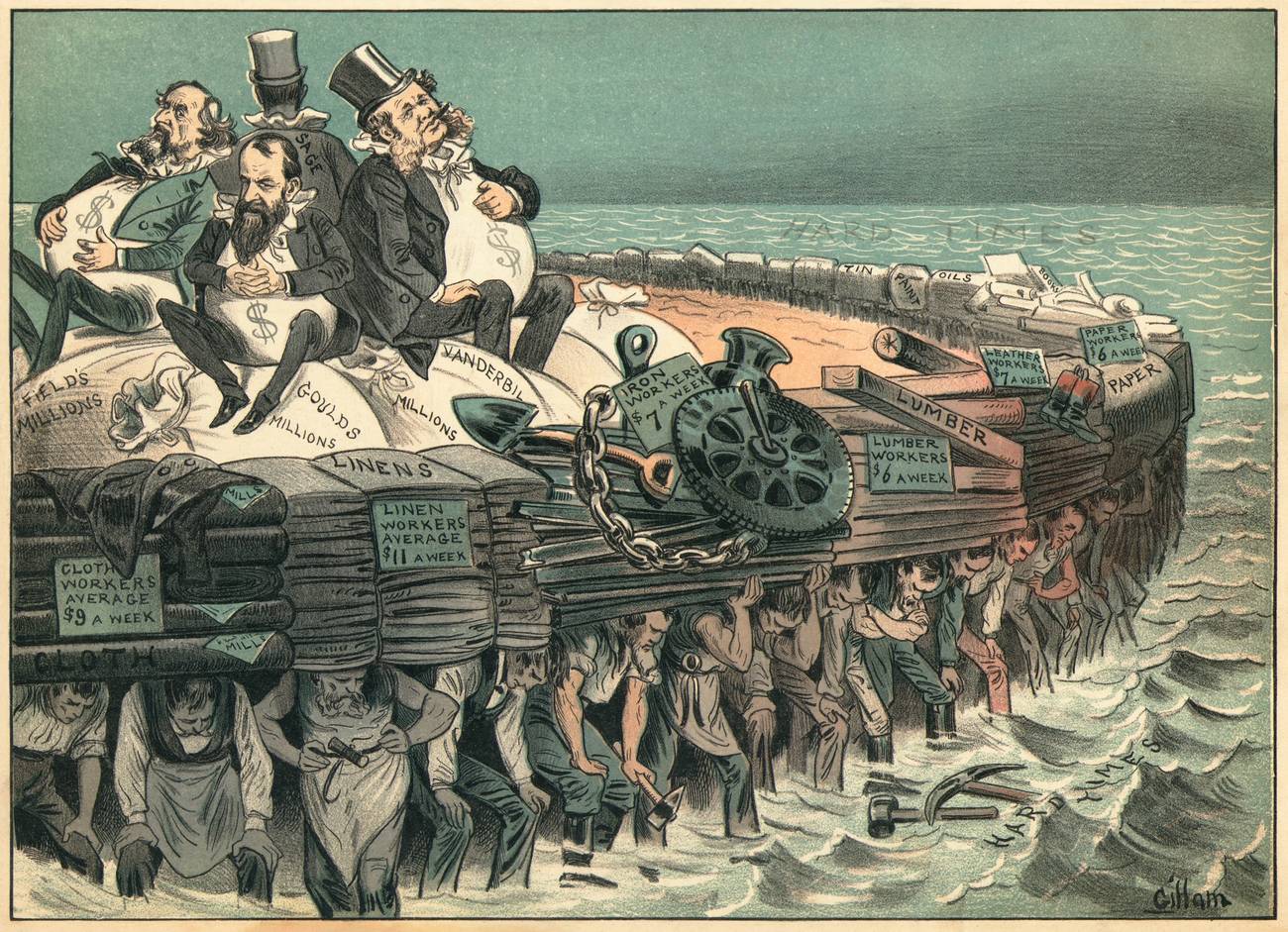

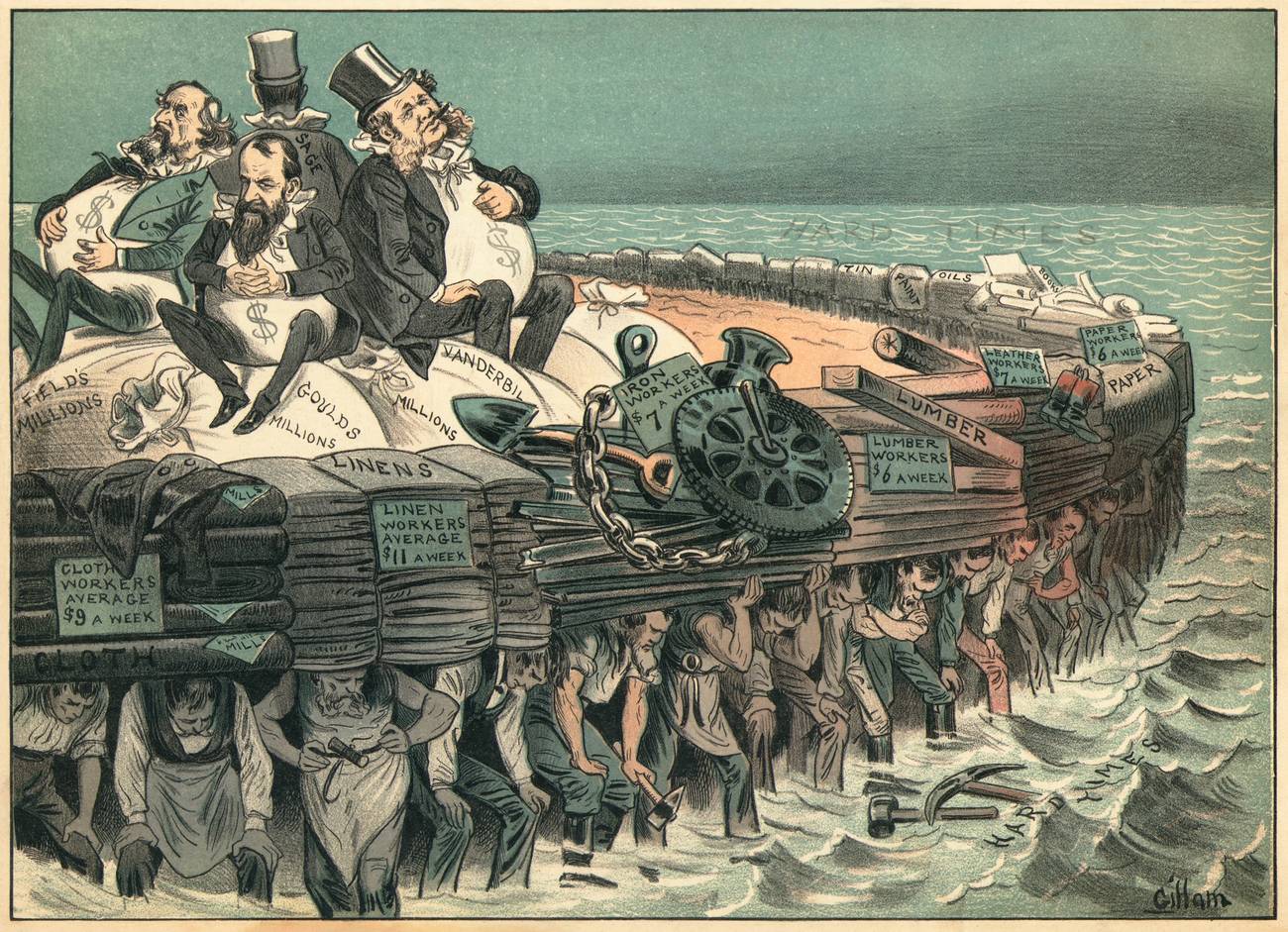

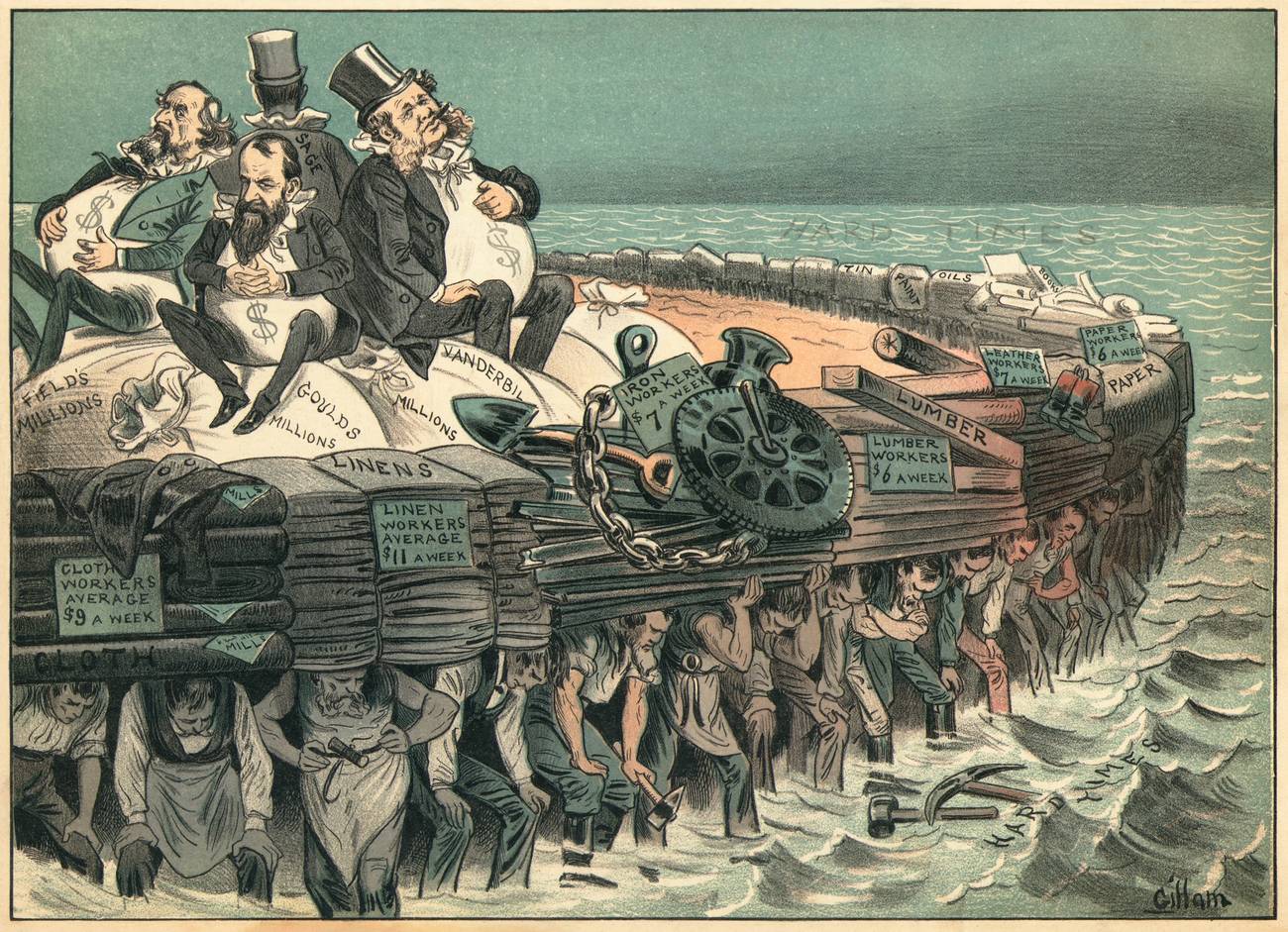

In the first era of industrialization, from around the 1830s to the 1880s and 1890s, railroad companies were almost the only large-scale, national enterprises. The first American industrial plutocrats were mostly railroad tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, Leland Stanford, Jay Gould, and E.A. Harriman. These predatory infrastructure monopolists were called “robber barons” after the medieval German aristocrats who exacted tolls from travelers on the Rhine. They bribed legislatures and arranged for the National Guard or U.S. Army to put down railroad worker strikes. They built palaces in Newport, Rhode Island, and scoured Europe for artistic treasures. Their era is remembered as the Gilded Age, after the title of a satirical novel that Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner published in 1873.

Modern industrial corporations, including many familiar names like GE and Ford, emerged a generation later from waves of consolidation between the 1890s and the 1930s. It was in this period that American managerial capitalism took on its familiar form—along with the class war and the culture war between the economic elite and the working-class majority.

Here are a few of the economic and cultural conflicts in the American class war that have been similar from the 1920s to the 2020s.

Organized labor. Like today’s Silicon Valley founders and CEOs, the capitalists and managers of a century ago resisted sharing power with trade unions. But while the new industrial capitalists could be as brutal in breaking strikes in the 1920s and 1930s as the railroad barons in the 1870s and 1880s, many preferred to pay lip service to harmonious labor-capital relations while engaging in various kinds of employer paternalism, including company unions and welfare-capitalist benefits for employees. In the same way, today’s big corporations endorse identity-based social movements while opposing unionization and refusing to share actual power with their workers.

Cross-border labor arbitrage. For a century, American industrial corporations have maintained their hold over their workforce by engaging in labor arbitrage—the strategy of avoiding unionization or the need to pay high wages by shutting down plants and moving them to other jurisdictions with cheap, nonunion labor. In the early 20th century, the American textile industry migrated from New England to the former Confederate states, whose shattered economies offered a wealth of cheap white labor. After World War II, Southern and Southwestern states used anti-union “right to work laws,” low minimum wages, and low taxes to lure factories from the North and Midwest to the Sun Belt. American corporations had decades of experience in labor arbitrage within the United States’ own borders before they began applying the same strategy by offshoring production to low-wage, repressive regimes like China.

Maximizing low-wage immigration. Between Reconstruction and the 1920s, the industrial corporations of the Northeast and Midwest used poor immigrants from abroad as well as impoverished Black and white workers from the post-Reconstruction South as “scabs” to break strikes, keep wages low, and make unionization more difficult. In 1875 a manager in one of Andrew Carnegie’s Pittsburgh factories admitted to using ethnic diversity as a divide-and-rule strategy: “My experience has shown that Germans and Irish, Swedes, and what I denominate Buckwheats (young American country boys), judiciously mixed, make the most effective and tractable force you can find.” In April 2020, Business Insider obtained secret internal documents from Whole Foods which similarly showed the company’s knowledge that stores in areas with few immigrants and low racial and ethnic diversity were more likely to unionize—and were therefore presumably to be avoided.

Fighting back against cheap-labor immigration policy, American organized labor played a key role in pressuring Congress to pass a series of laws that shut down the use of indentured servants and immigrants from Asia, beginning with the Chinese exclusion act of 1882 and completed with the national origins act of 1924, which established a system of European nationality quotas, biased toward the “old immigrant” homelands of Britain, Ireland, and Germany, within an overall white-only immigration policy that lasted until the immigration and naturalization act of 1965.

The members of the American elite who supported immigration restriction a century ago did so in spite of their interests as employers of workers and servants. Many were motivated by ethnic bigotry, racism, and fear of the loss of Anglo-American Protestant hegemony in the United States. Support for immigration restriction by organized labor and African Americans sometimes also took on racist overtones, but these groups viewed immigrants chiefly as economic rivals. Even though the 1924 act sharply restricted the immigration of Jews and other Europeans, American Federation of Labor President Samuel Gompers, himself a Jewish immigrant, supported it on the grounds that high levels of immigration “must of necessity have a tendency to reduce the wages of the people of this country.”

The protoplasmic blob in an abstract painting on the wall would gaze lovingly at a Noguchi coffee table, a glass amoeba with two wooden pseudopods that bore ‘The Joy of Sex’ on its back next to the latest issue of ‘The New Yorker.’

The Black civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph is best remembered today for forcing President Roosevelt to integrate war industries during World War II by threatening a march of African Americans on Washington, D.C. Later he was one of the main organizers of the 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington. Earlier in the 1930s, as founder and leader of the all-Black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union, Randolph backed legislation to block noncitizens from working as railroad porters to thwart an attempt by the Pullman corporation to use nonunion Asian guest workers to replace Black union workers.

In 1924 Randolph explained his support for restrictive immigration legislation: ”Instead of reducing immigration to 2% of the 1890 quota, we favor reducing it to nothing ... We favor shutting out the Germans from Germany, the Italians from Italy ... The Hindus from India, the Chinese from China, and even the Negroes from the West Indies.” He declared that immigration “over-floods the labor market, resulting in lowering the standard of living, race riots, and general social degradation. The excessive immigration is against the interests of the masses of all races and nationalities in the country—both foreign and native.” Indeed, the nearly complete shutdown in the 1920s of low-wage immigration from Europe created enormous opportunities for African Americans, in roles other than company-sponsored, union-busting strikebreakers, in the industrial North between the 1920s and the late-20th-century offshoring of American manufacturing.

Following World War II, organized labor and pro-labor liberals fought the Bracero program—a 1941 law that allowed Southwestern agribusiness to exploit Mexican guest workers rather than hire Americans and pay them a decent wage. President John F. Kennedy observed, “The adverse effect of the Mexican farm labor program as it has operated in recent years on the wage and employment conditions of domestic workers is clear.”

In the 1970s, the leader of the United Farm Workers, the Mexican American labor activist Cesar Chavez, denounced lax enforcement of border security and workplace laws, which allowed Southwestern agribusiness to use illegal immigrants to thwart unionization. But agribusiness won. Today the share of agricultural work performed by illegal immigrants without legal and labor rights is higher than it was in the 1970s.

In the midst of the greatest mass unemployment since the Great Depression, American business lobbies continue to claim they are suffering from labor shortages, which only higher immigration levels can cure. Silicon Valley and Wall Street, through well-funded pressure groups like Mark Zuckerberg’s Fwd.Us, lobby to expand today’s version of the 19th-century Asian contract labor or “coolie” trade—importing noncitizen indentured servants with H-1B nonimmigrant visas, mostly from India, to work in the United States for lower pay than Americans in their field and with fewer legal rights. In their support for ever-higher levels of immigration, along with their opposition to effective penalties against employers who hire illegal immigrants, today’s American employer lobbies are as self-interested as those of the 1890s and the 1920s. For its part, what is left of organized labor, dominated by public sector unions whose members do not compete either with immigrants or workers in other countries, has sacrificed its historic wariness toward mass immigration to conform to the new woke Democratic Party line that immigration enforcement is racist.

Corporate feminism versus the family wage. Following the logic of capitalism, business elites from the 1920s until the 2020s have often sought to create a buyer’s market in labor by maximizing the number of women, including mothers of young children, in the labor market. Against this policy, American organized labor, populists, and religious traditionalists favored the idea of a “family wage,” which would pay a married working man enough to support not only himself but also a homemaker wife and two or three children. New Deal Democrats, including feminists like Eleanor Roosevelt and Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, took the side of working-class Americans against employers and favored protective legislation for women and the family wage.

This explains why, in the heyday of union power before the 1970s, the AFL and other unions often opposed legislation mandating equal pay for men and women of the kind supported as early as 1904 by the National Association of Manufacturers.

It also explains why, in its 1976 party platform, the Republican Party—then still the “country club” party of investors and managers and professionals, not workers—boasted: “The Republican Party reaffirms its support for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. Our Party was the first national party to endorse the ERA, in 1940.”

Reproductive and sexual liberty. While the United States population has grown more liberal over time, America’s economic elite has usually been well to the left of the working-class majority of all races and ethnic groups on matters like contraception, abortion, divorce, and other issues of sexual freedom. For generations, rich Republicans were the chief supporters of Planned Parenthood and similar organizations, in part out of a desire on the part of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) to minimize the birth of allegedly “inferior” white “ethnics” and poor Southern whites along with nonwhites by means including birth control, abortion, and, in the early 20th century, compulsory sterilization.

Having succeeded in enshrining abortion rights in the U.S. constitution, beginning with the Roe v Wade decision in 1973, the intellectual heirs of the upper class Planned Parenthood Republicans of yesteryear—most of them affluent Democrats now—continue to push the envelope, demanding the legalization of late-term abortion, which is hard to distinguish from infanticide. Many support the legality of paid surrogacy and the legalization of prostitution, two practices which, from a pro-labor perspective, are horrifying examples of the degradation of human beings in return for money.

Big Philanthropy. Today’s Silicon Valley and Wall Street tycoons who endow foundations bearing their names—Gates, Bloomberg, Milken—are little different from Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller a century ago.

In his 1889 essay “The Gospel of Wealth,” Andrew Carnegie, the immigrant Scottish American steel magnate who built his fortune on brutal treatment of American workers and the suppression of organized labor, declared that society was better off when the benevolent rich were allowed to spend their fortunes on charitable causes than when they were taxed to pay for public spending directed by politicians. Recently Bill Gates made a nearly identical argument, claiming that governments are so incompetent that large-scale spending decisions are best entrusted to enlightened billionaires like himself: “Philanthropy is there because the government is not very innovative, doesn’t try risky things and particularly people with a private-sector background—in terms of measurement, picking great teams of people to try out new approaches. Philanthropy does that.”

For a century labor leaders and populists have replied to such self-serving arguments by asking arrogant plutocrats like Carnegie and Gates an obvious question: “If you have enough money to endow a foundation, why don’t you pay your employees more?”

Theodore Roosevelt, who despised Carnegie, observed privately: “All the suffering from Spanish war comes far short of the suffering, preventable and non-preventable, among the operators of the Carnegie steel works, and among the small investors, during the time that Carnegie was making his fortune ...”

Modernism in the arts. Even in matters of art and fashion, American business elites and the working-class majority have been at odds for a century. America’s 20th-century managers and capitalists as a rule have been more avant-garde in their tastes than most of their fellow citizens. The Rockefellers and other plutocrats patronized the Museum of Modern Art, which during and after WWII dismissed the kinds of figurative art and traditional architecture that the working class liked as “kitsch” (trash) and smeared it by comparing it to Nazi and Soviet propaganda. Despising popular figurative painters like Norman Rockwell and later Thomas Kinkade has been a marker of ruling class membership for nearly a century. Vulgar, rich arrivistes like Donald Trump may favor traditional architectural ornament, but the taste-makers in the business community for decades promoted sterile glass-box International Style architecture and abstract painting and sculpture as the more or less official style of corporate America and the Free World.

Now more than a century old, the modern style long ago ceased to be modern. Herbert Hoover’s ultramodern house, now owned by Stanford University, was built in 1919-20. The ambition of many corporate executives and professionals of the mid-20th century was to live in a home inspired by the Glass House of Philip Johnson, the court architect of the Rockefeller dynasty. The protoplasmic blob in an abstract painting on the wall would gaze lovingly at a Noguchi coffee table, a glass amoeba with two wooden pseudopods that bore The Joy of Sex on its back next to the latest issue of the New Yorker.

The post-New Deal new normal, then, is very similar to the pre-New Deal old normal. The present is not a rerun of the age of the age of robber barons after the Civil War, but of the subsequent age in which university-credentialed corporate elites have usually favored free markets and free love and freedom from organized labor, while working-class populations, white and nonwhite, have typically favored a mix of moral traditionalism with pro-labor protectionism in economic policy.

This is not the second Gilded Age. It is the second Jazz Age. And from the perspective of America’s disfranchised and alienated working-class majority of all races, that is bad enough.

Michael Lind is a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.