A 20th Century Jewish Life

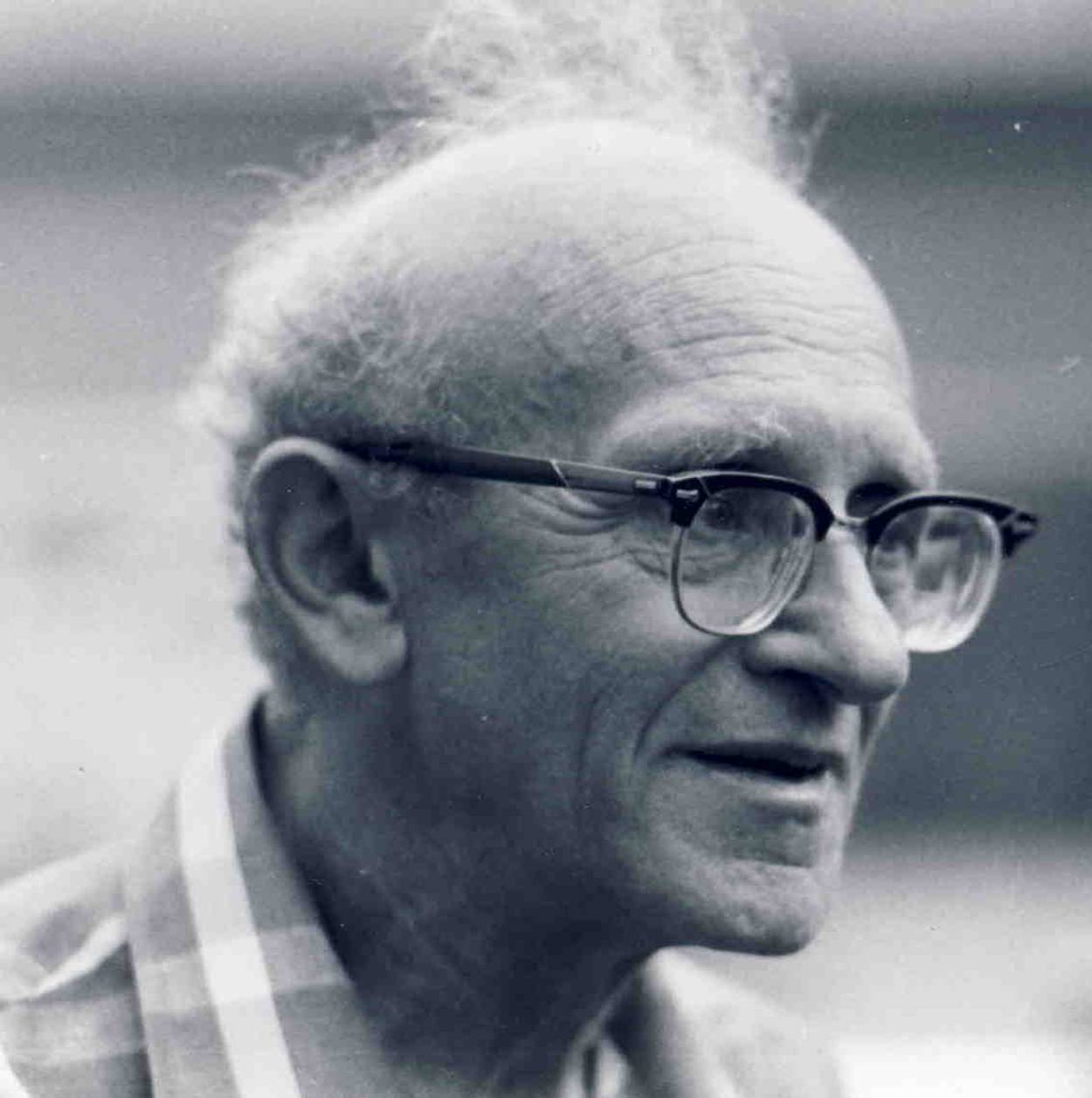

Scientist, Zionist, man of nature: My father, the biologist Jacob Biale, represented all the possibilities of Jewish American life

My mother had called on a Friday. “You’d better come down,” she said, “it looks like this is the time.” His prostate cancer had come back a little more than a half a year before. The last time he had been fully himself was the previous Thanksgiving, when he and my mother had come up to Berkeley, as had been their custom since we moved back to California two years before. We had taken my son to a local park and my father, now 80 years old, had played hide-and-seek with him, revealing that a young man still hid within his aging body. And when he put my 3-year-old daughter down for a nap, she came downstairs after a while and announced: “The old man fell asleep!” But it was hard to think of him as old. His spirit was still young and it seemed as if his life repeatedly moved the goal posts of age: If he was 80, then old age must begin at least at 85.

Over the next half year, he began to weaken and tire. He lost weight, something of which his small, trim frame had little to spare. I flew down to LA at one point and helped take him to the doctor, an old family friend who, as an undergraduate, had taken biology with my father as the professor. After examining him, he called my mother and me back in the room and discussed the results of the tests with all of us. He knew better than to insult my father’s intelligence by interpreting what was obvious. “You know what this means, don’t you?” he asked gently. My father nodded. No dramatic words. Just the unvarnished scientific truth: the most fitting way to convey a death sentence to an old biologist.

In the spring, he insisted—despite his illness—on teaching a freshman seminar on “The Origins of Life.” Ever since retiring some 13 years earlier, the UCLA Biology Department had called him back to do some teaching. He was an extraordinarily devoted teacher. He didn’t hold office hours. Instead, he told the students that they were welcome to drop into his office whenever he was there—which was pretty much all the time. Now, he had a group of first-year students, many of them nonscientists and he was conveying the love of science that had animated his life. They must have been aware that something was increasingly wrong with the short, mostly bald, kindly professor with the vaguely European accent. In their course evaluations which I read later, you could see the affection and admiration they had for him, even though this couldn’t have been his best teaching effort.

One time, I took him to the UCLA campus to pick up some papers. By now, he tired so quickly that walking was an effort. This was a man who had spent his whole life hiking—from the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement in Poland to treks in the Himalayas and—closer to home—backpacking in the Sierra Nevada. Even in his 60s, when we went backpacking, he would proceed at a very slow, deliberate pace, one foot in front of the other, falling way behind the rest of the—much younger—party, but always arriving, scarcely out of breath. Now, as I saw him walking alongside his building to meet me, he seemed so diminished, hardly himself. But what still was the father I grew up with was no longer his body, but the fierce determination to put one foot in front of the other.

He lived his life as a secular Jew, but not an unaffiliated one. To be sure, the usual kind of Jewish institutions were not for him. We joined a synagogue for the year of my bar mitzvah, but after I cut class one too many times, we let our membership lapse and my father and I decided to do our own bar mitzvah in the backyard (it was the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis; we read Isaiah on world peace).

My father’s affiliation was of his own making. Together with a group of left-wing Zionist friends, he formed a group—Migdal—in the early 1940s. Gathering for earnest monthly meetings on Jewish affairs of the day, they created a little Zion in Los Angeles, a mini-Jewish state for those too timid or too settled to emigrate to the real Promised Land. They also gathered to celebrate the Jewish holidays together. These were my fondest Jewish memories growing up. The second night of Passover, after surviving the stultifying first Seder at my mother’s family, some 75 or a hundred Migdalites would assemble in some community center. A communal spirit took hold as men set up tables and chairs, while women took over the kitchen (egalitarianism had its limits here, as it did in the real kibbutz that Migdal wanted to emulate). By unwritten rule, my father assumed the role of the patriarch, presiding over the ritual by doling out the assigned readings (the most these secularists would concede to religious practice was to use the Reconstructionist Haggada).

His secularism would be sorely tested when my sister joined Lubavitch and became an ultra-Orthodox Jew. Here, the tables of history seemed to have turned. Immediately after her marriage, my sister cut off her hair. This cut my father to the quick. The rest he could comprehend. But since he had so much pride in his own mother’s courageous decision to grow her own hair, my sister’s donning of the sheitl seemed like turning progress directly on its head. In the end, though, the gene for tolerance he had inherited from his own father found expression. He came to accept my sister’s Orthodoxy much more easily than my mother, who, because her own parents had already fallen away from religion, had never herself rebelled against tradition.

Every Passover, my father would make a stilted speech in memory of his parents—and the Six Million—as he lit a special yahrzeit candle. What he really felt remained murky. I remember learning about the Holocaust at around age 11, probably in connection with what happened to his parents. I can still recall the bottomless terror at the idea that every Jew in Europe was doomed to extinction, a death sentence that we had only escaped because of decisions that my mother’s parents and my father had made to become immigrants. My uncle and aunt, who had been in the Russian-occupied zone of Poland in 1939 and therefore survived the war in Stalin’s gulag, were the self-conscious and self-identified survivors of our family.

In his case, it was Zionism that saved him since, with his friends, he was determined to get a scientific education in agriculture before becoming a pioneer in Palestine. And, so, to the San Francisco Bay Area, where his father’s brother and two sisters (as well as his grandfather—his father’s father—a figure he never mentioned) had immigrated years earlier, becoming, of all things, Christian Scientists. His father accompanied him to the train that took him to Hamburg and, from there, by ship to New York.

He recorded his memories of that leave-taking in a diary written in a flowery Hebrew that began with the acknowledgement that he had just ended the intensive, romantic phase of his life in the youth movement that would mark it henceforth. He was met by comrades in the movement and then put on another train, this time across the U.S. In the Southwest, he stopped to buy his brother a bow and arrow, for the romance of the American West was still powerful in interwar Poland. He arrived in Berkeley, knowing almost no English. A sympathetic professor of chemistry conversed with him in German, a language he had learned in his gymnasium. But an essay that I found after his death, written that year, demonstrated an astonishing command of English, far beyond what might have been expected (the hand in which that 1928 essay was written was virtually identical to the one I knew from a half century later). Here was evidence of a motivation and drive to adapt to a country that he had initially, at least, only seen as a way station to the Promised Land.

After a semester at UC Berkeley, he was sent up to “The University Farm” at Davis, where, by a fluke of history, I was to end up on the faculty exactly 70 years later. I recently discovered his transcript with his grades in various agricultural courses such as irrigation, pruning of fruit trees, and so forth. His grades were mostly B’s, with the ironic exception of consistent C’s in physical education. It is hard to imagine this short, slightly awkward Polish Jew, with little English, studying agriculture together with farm boys from California’s Central Valley. What could they have had in common? He supported himself with orchard work, sending whatever he had left over back to the family in Poland. In the depths of the Depression, if one could find work, the few dollars earned every week sufficed to pay for room and board with something left over.

In Berkeley, he became part of the “Palestinian” group (which, in those days, was all Jews). After finishing his doctorate in 1934, he struggled to find a position in the midst of the Great Depression. After his death, I uncovered correspondence that suggested that he seriously considered an offer of work in the Soviet Union. The particular subdiscipline that had attracted his interest—the way plants regulate their water supply—was evidently being pursued most vigorously there. But I could not help but wonder if his Hashomer ideology didn’t play a role. By the 1930s, the movement, which had started out as a romantic Jewish version of the German Wandervogel, idealizing nature and rebelling in Nietzschean fashion against bourgeois Jewish life, had become Stalinist (a position it clung to stubbornly until well into the 1950s). Could his attraction to the Soviet Union—two years before Stalin’s Great Purge—have been more than purely professional?

Fortuitously, though, the United Fruit Company wanted to know why citrus fruit was developing molds in transit and offered the School of Agriculture at UCLA $5,000 to find out the answer. No one there was interested, so they hired my father for a year. He figured out a piece of the puzzle—and stayed 55 years. From there on, his commitment to science rivaled his Zionism. In 1958, he had the opportunity to combine them by taking up a United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization post for a year in Rehovot, Israel. There, he was like a kid in a candy store, speaking his slightly archaic, literary Hebrew to anyone he could accost (he would get lost, seemingly on purpose, so as to ask directions) and touring the country tirelessly as if to breathe in its odor of citrus and cyclamen.

It was not his first time in Israel. In 1954, he organized a trip there at a time when few tourists made the trek to that far corner of the Mediterranean. He wrote voluminous letters home, filled with new impressions and the excitement of discovering the reality behind his boyhood dreams. Traveling the length and breadth of the land, he wrote of the incessant building he saw everywhere: “It seems like the Jews have really come here to stay.”

For me, the year we all spent in Israel was transformative. The country was minuscule, Spartan and socialist, or so it seemed. As the popular saying had it: “klein aber mein”—“small but mine.” The Lod airport was a squat, tiny building, much like one sees today in the Third World. When we landed, people were gathered on the roof, waving and cheering. Young as I was, I felt as if I had come home. It was the best year of my childhood.

My mother’s experience was the opposite: She cursed the dingy basement apartment and my father’s old friend who had found it. (Zdenka Samisch was a member of the Palestinian delegation of students at Berkeley and was now a member of the Faculty of Agriculture in Rehovot; my mother accused my father of having an affair with her, thus demonstrating her utter ignorance of the much deeper passion that the two of them shared for Zion.) She used her Yiddish with the local grocer but made little effort to learn Hebrew.

Everything about the place she found repellent. When, by the end of the year, he had an offer of a job in hand, she would hear nothing of it. We returned to Los Angeles, she in triumph to her family and he, no doubt, silently bitter at the defeat of his lifelong dream.

Their marriage was not easy, although it was not until I was nearly an adult that it became apparent to me. They married in 1945, after having met in the basement of the Physics Building at UCLA, where he had his laboratory and she was working as a teaching assistant for introductory physics classes. She had come to the West Coast to represent the East Coast branch of her family at the wedding of her cousin Rita. This was in 1940. She had just finished a master’s degree in mathematics at Boston University, an extraordinary achievement for a woman in those days. She was able to secure employment at the U.S. Naval research base in San Diego where work was going on in developing radar. When she discovered, though, that the job was more clerical than scientific, she moved to LA and found work at UCLA. Her promise received recognition from at least one UCLA professor, who encouraged her to take a higher degree in meteorology, a suggestion she spurned, to her lasting regret. They shared a love for folk dancing, hiking in the Sierras and politics. (Their letters from the 1940s are filled with political comments and references to important meetings; visiting Berkeley in 1945, she wrote to him that she was going to meet members of the Berkeley Graduate Student Association because “she couldn’t imagine not being involved in some form of politics.”)

But his Zionism was alien to her. Her family, poor Jews from Ukraine, had come to the United States in 1912, part of one of the greatest movements of Jews in all of history. Her father was a dish decorator, a craft he had learned in the Old Country. Her mother, who never learned to read in any language, had tended the family ferry outside of Zhitomir and had finally run off to America with an elder brother with the money she surreptitiously saved from the drunken peasants who regularly beat her. When she landed with her brother in Boston, he told her that she was on her own. Having married my grandfather, who came from the same shtetl, they made a life in Auburndale near Boston by the railway tracks. During the Depression, when he lost his job, they would collect blackberries by the tracks, barely managing to scrape by.

This—and not the dream of a reborn Jewish State—was the crucible that formed my mother, as it formed her parents. They were Jewish in the way that most immigrants were Jewish: an ethnic identity so basic that it required no convoluted thought. They had abandoned most of the Orthodox Jewish law not long after their immigration, not because of some religious opposition, but because it seemed ephemeral to the real core of their Jewishness (when my grandmother called what she spoke “Jewish,” she was not only translating the word “Yiddish” into English, but also suggesting the intimate tie between language and identity). The ideological passions of modern Jewish life were foreign to them, although they had lived, without fully knowing it, one of its greatest dramas. And, so, my mother could not share my father’s profoundest passion, indeed, had to learn it as a virtual foreigner, never embracing the new land to which he had introduced her. The very thought of moving there was too frightening and occasioned the great rebellion that led both of them back to California.

He, too, found marriage a challenge. His formative experience was of the collective, the group that nourished his ideology. It was this that he sought to replicate in Los Angeles. Both the ideology and the reality of the group militated against personal relationships (the movement sucked up all the romantic oxygen). In his papers that I went through after his death, he wrote passionate letters in flowery Hebrew to a variety of women back in Poland—and similar letters to a variety of men. In the late 1930s, he apparently had a brief fling with a woman who wrote him several letters revealing how deeply hurt she was by the way he withheld his affection. Since only the letters to him survived (and, typical of him, he saved them along with every other scrap of memorabilia), it is necessary to reconstruct from them what he said to her. But the gist seems to have been that individual, romantic relationships were not in his repertoire.

Why then he chose my mother—an American-born non-Zionist—remains a mystery. Perhaps at age 38, he had come to the realization that he would have no progeny if he did not marry. Perhaps he did fall in love with her. The answer he took to his grave. His ideas of marriage were certainly unconventional: As my mother related after his death to my astonishment, he took along two female undergraduate students on their skiing honeymoon! Instead of the usual professorial seduction of his student, he used these students for the exact opposite purpose: to neutralize the “bourgeois” institution of the honeymoon by rendering it another outing of the youth movement.

It is clear that within a few years of marriage, the relationship had become tenuous. In 1948, after less than three years together, he went to England for a six-month sabbatical and she remained behind in Los Angeles. He had evidently persuaded her that England still recovering from the effects of the war was no place for her, while he was spending virtually every waking hour engaged in science. But by the time several months had elapsed, she exploded in recriminations. In a bitter exchange, he made it clear that she should not expect more from him than cool companionship. He was not suited to married life, he said. Although they managed to work through the crisis—preserved in painful detail in their letters—a residue remained, to be resurrected by her after his death.

He wrote almost every day, but his letters read less like those of a passionate lover than of a singularly devoted travel journalist. He writes of his immersion in scientific work in London and Oxford (with the future Nobel Prize winner and discoverer of the Krebs cycle). He describes England and his social life there in vivid strokes. He writes of an encounter on the boat with a young man who had spent the war years in a Nazi camp in the Polish town of Oswiciem (the name Auschwitz had still not entered the vocabulary). Without any details, he makes clear that he learned rather more than he wanted to know about that experience. And when he traveled to Denmark, he writes that Poland lies so close that it would take almost nothing to jump over there for a visit. But, he says, he must resist the temptation for “the past is a book that must remain closed.”

The Holocaust (also not yet a word in the vocabulary) could not have been far from his mind. How much had he known during the war? I remember after reading a number of books on the question of what American Jews knew, asking him about his own experience. After all, with two parents in Poland, he had a much more pressing reason than most American Jews to find out the truth of what was going on under Nazi occupation.

Through his Zionist contacts, he had access through Switzerland to the Warsaw Ghetto, at least until the Great Deportation began in July 1942. He sent to and received letters from his parents from the time they were expelled—along with the rest of the Jews of Wloclawek—to Warsaw. The letters were written in German for the benefit of the censor; the envelopes bear the stamps of the Nazi “General Gouvernement” of Poland. In a letter from his mother written only eight days after the ghetto was closed (Nov. 1, 1940), she says that they are well, but they are deeply worried about his sister, Frania, and her husband, Shimon, who were in a Soviet camp in Archangel (they were apparently able to write to them during the period before the Nazi invasion of Russia and she asks whether my father has received their address). She also speaks of their helplessness and despair at not having any news of his brother, David. Apparently, the news of his death as a soldier in the Polish Army, which took place sometime in September 1939 in Lvov, had still not reached them. It was through those letters that he learned of his father’s death from typhus in the ghetto in December 1941.

But beyond the terrible conditions in the ghetto, most of which his parents concealed from him, he knew nothing of the actual genocide. It is likely that his mother was deported to Treblinka sometime between July and September 1942, when most of the Jews of Warsaw were massacred by gassing. But that was news he learned only after the war, probably when my aunt and uncle, returning from Central Asia, passed through Poland on their way to Chile (and subsequently, with his help, to California). The awful truth remained shrouded until nothing was left of the 3 million Polish Jews. This was the book that he dared not open as he looked over the eastern horizon from Denmark.

But there was more in the book than I knew growing up. After he died, when I sat with my mother in our own rough approximation of the traditional shiva, she erupted in a litany of complaints and recriminations, a kind of countereulogy. The bizarre honeymoon, his failure to take her on the English sabbatical, his many, long trips abroad (Israel, Russia, Nepal, the Amazon), leaving her at home with small children and house construction, the humiliations and sufferings of the year in Israel, his sabotage of her piano playing (a talented pianist, she had had her sheet music shipped to LA, only to have it “disappear” from his laboratory where it was being stored)—all of these came back up to the surface. Some—but not all—of them were familiar to me, but her picture of my father was so at odds with the one that I—or his many friends—had, that it was hard to know if we were talking about the same man.

And, then, more or less in the middle of a sentence, she slipped in: “You know, of course, that your father was married before we got married?” She moved right on to another complaint, but I brought her up short: “What was that you just said?” She actually knew very little. When he had asked her to marry him, he had revealed that he had previously been married and showed her a copy of the get (the traditional bill of divorce) he had given his first wife. And then he said, using the same phrase as in his letter: “the past is a book that must remain closed.” He never wished to speak of it again and, apparently, they didn’t.

Knowing his propensity to save everything, I went directly to his office and rummaged through the drawers. Sure enough, there was a whole file with letters, the get and even a few pictures. Since my uncle and aunt were the family historians, it occurred to me that they could surely shed light on this surprising turn of events.

A simple phone call revealed that they did indeed remember the circumstances. Her name was Kala and they knew her family quite well. She was a member of the youth movement. In the summer of 1934, he had returned to Poland, Ph.D. fresh in hand, to visit his family for what would be, unbeknownst to them, the last time. There, apparently quite precipitously, the two decided to marry in a civil ceremony that was not attended by their families. He returned to the United States with the goal of securing her a visa. They exchanged letters, some of them in English, which she was in the process of learning.

But, then, things went disastrously awry. The Immigration Service challenged his citizenship on the grounds that he had lied about his student status. The case dragged on for years and he was in real danger of deportation back to Poland on the eve of the war. The case actually went all the way to the United States 9th Circuit Court of Appeals where, in 1938, his citizenship was upheld. But, by then, it was too late. She had given up in despair, found another man, a teacher, with whom she had a child (she revealed all of this in a letter acknowledging the divorce papers he sent to her). Her precise fate, and that of her family, is unknown, but it is certain that they all died in the Shoah.

This was the burden that he carried silently with him. In addition to his failure to have saved his own parents, he labored with the knowledge that his legal difficulties had doomed his first love to death at the hands of the Nazis.

That my father never mentioned any of this can be interpreted in many ways, and the right interpretation cannot be known. Was his difficulty in establishing a new marriage a result of his guilt over the old one? Was he, despite all evidence to the contrary, a true romantic after all? Or, perhaps this was a book that he had closed forever. But if he had, he certainly left sufficient evidence behind for anyone with sufficient curiosity to open it again.

As he lay dying in the early summer of 1989, just as the Soviet Union began to crumble, I remarked to him that he had seen quite a bit of the 20th century: born in the Russian Empire, with memories of the German Army marching through his town in 1914, the Russian Revolution and Soviet-Polish war (he was sent on an errand for his father as what he described with some pride as “Trotsky’s Army” bombarded Wloclawek and was forced to return home empty handed), the Holocaust, the birth of the State of Israel and now the fall of Communism. A Jewish life in the 20th century.

A friend of mine, on the medical faculty at Toronto, dropped by to see him. Robert had always admired my father, as a scientist, a Jew, and a human being. My father rallied briefly and asked him what he was working on. “Hematopoiesis,” Robert answered. He nodded and smiled briefly. A good subject, one of the infinite building blocks of the origin of life to which he had so recently devoted his teaching.

Robert checked his wrist and called me outside. “He’s very dehydrated,” he reported, “what do you want to do, take him into the hospital to get an IV?” This wasn’t a decision for me. We went back in and asked him: “You’re dehydrated. Do you want to go to the hospital?” Weak as he was, his voice was adamant: “No, no hospital.”

A little later in the day, his own physician dropped by. House calls may no longer be in the medical repertoire, but for Maury Yettra, who had pioneered hospice care in the Los Angeles Kaiser medical group, it was an obvious gesture to be made to a dying old friend. His examination revealed dehydration as well, plus, he thought, a touch of pneumonia: the “dying person’s friend,” as he put it. He took me aside and explained what to expect: “He won’t last more than a day or so and the pneumonia will carry him off. Look, he’s likely to experience some discomfort near the end. I’m going to give you this syringe of morphine. You should give it to him if he seems to be restless. Here’s how you give him the injection.” He paused. “You realize, don’t you, what it will mean if you give it to him?” He didn’t need to elaborate on how the morphine would stop his breathing, given how impaired it was from the pneumonia.

My sister arrived the next morning with her newborn daughter and put her on the bed next to him. A strange gesture: new life next to imminent death. But this sister was famous for her strange gestures. While my other sister had embraced ultra-Orthodoxy, this one renounced her Jewish identity and married a Chicano construction worker (a marriage later doomed to disaster). Between the three of us was the whole spectrum of Judaism in the post-assimilationist age, trajectories that my father could never have dreamed of in his native land.

We set up a baby monitor so that we could hear him as we sat in the dining room trying to distract ourselves. At one point, I went to check on him and he was clearly experiencing the restlessness that Dr. Yettra had described, tossing, turning, and moaning. Without more than a moment’s thought, I took out the morphine syringe and injected his wasted leg. The last gift a son could give to his father. And, then, as we continued to keep watch at the dining room table, following in the background his regular breathing on the monitor, I noticed a sudden pause: The moment between life and death passed so fleetingly that it almost passed unnoticed.

He is buried, incongruously, in a Jewish cemetery overlooking the San Diego Freeway. The central feature of the cemetery is a mausoleum to the great Hollywood actor Al Jolson, who presides over the assembled children of Israel in their respective grave sites. All this is alien to who my father was: a scientist, Zionist, and man of nature.

Into his grave, we placed a branch of a redwood tree and another heavy with avocados. Both were from the house in which he had lived for the previous 47 years and from trees he had planted. The avocado was the fruit on which he had showered his scientific curiosity (the 1952 issue of Scientific American in which he published an article on his research had on its cover a photo from his lab of a respiration jar of avocados), as well as the fruit that he helped introduce to the young State of Israel.

The redwood was an oddity in Southern California and, like my father himself, it somehow stubbornly survived there despite the inhospitable climate. He insisted on nurturing it, believing that he could make it live. It was a sign that despite his 55 years in Southern California, his heart was still in the northern part of the state, where the redwoods flourished and where he had first set down roots on the American continent.

David Biale is Emanuel Ringelblum Distinguished Professor of Jewish History at the University of California, Davis. He is the author or editor of 11 books, of which the most recent is Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah.