Needle Points

Chapter IV: Getting Out

Science has had many surprises for us in this pandemic. We’ve learned that while the vaccines don’t always stop the spread, they do protect the vaccinated from getting severe disease and death for a number of months. We’ve learned, as The New York Times points out, that “an unvaccinated child is less at risk of serious COVID illness than a vaccinated 70-year-old.” (Though we learned that Emily Oster, the author and academic who first called that fact to our attention, was mistreated for months because she was off-narrative.) We’ve also learned that you are safer in a room, or even on a plane, with people who have recovered from COVID than you are with people who were vaccinated (especially over four months ago). In other words, the immunity of those who suffered COVID is holding up so far.

So, why doesn’t good news like this sink in?

I submit that it’s because of our old friend, the behavioral immune system. Many people’s mental set for the pandemic was formed early on, when the BIS was on fire, and they were schooled by a master narrative that promised there would only be one type of person who would not pose danger—the vaccinated person. Stuck in that mindset when confronted by unvaccinated people, about half of whom are immune, they respond with BIS-generated fear, hostility, and loathing. Some take it further, and seem almost addicted to being scared, or remain caught in a kind of post-traumatic lockdown nostalgia—demanding that all the previous protections go on indefinitely, never factoring in the costs, and triggering ever more distrust. Their minds are hijacked by a primal, archaic, cognitively rigid brain circuit, and will not rest until every last person is vaccinated.

To some, it has started to seem like this is the mindset not only of a certain cohort of their fellow citizens, but of the government itself. Moreover, because COVID vaccine hesitancy is based in significant part on distrust of the government and related institutions, it has to be understood not only in terms of vaccines, but in the context of the pandemic more broadly—first and foremost, in other words, of the experience of lockdowns.

For many, trust was broken by the lockdowns, which devastated small businesses and their employees, even when they complied with safety rules, such that an estimated one-third of these businesses that were open in January of 2020 were closed in April of 2021, even as we kept open huge corporate box stores, where people crowded together. These policies were arguably the biggest assault on the working classes—many of whom protected the rest of us by keeping society going in the worst of the pandemic—in decades. That these policies also enriched the already incredibly wealthy (the combined wealth of the world’s 10 richest men—the likes of Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and Larry Page—is estimated to have risen by $540 billion in the first 10 months of the pandemic), and that various politicians who instituted lockdowns were regularly caught skirting their own regulations, solidified this distrust.

And yet, it is the unvaccinated whom many leading officials still portray as recklessly endangering the rest of the country. “We’re going to protect vaccinated workers from unvaccinated coworkers,” President Biden has said. The unvaccinated are now presented as the sole source of future variants, prolonging the pain for the rest of us. For those in favor of mandates, the vaccine is the only way out of this crisis. To them, the vaccine hesitant are merely ignorant, and defy science. We tried to use a voluntary approach, they believe, but these people are Neanderthals who must now be coerced into treatment, or be punished. Among the punishments called for is not just loss of employment, but also of unemployment insurance, health care, access to ICU beds, even the ability to go to grocery stores.

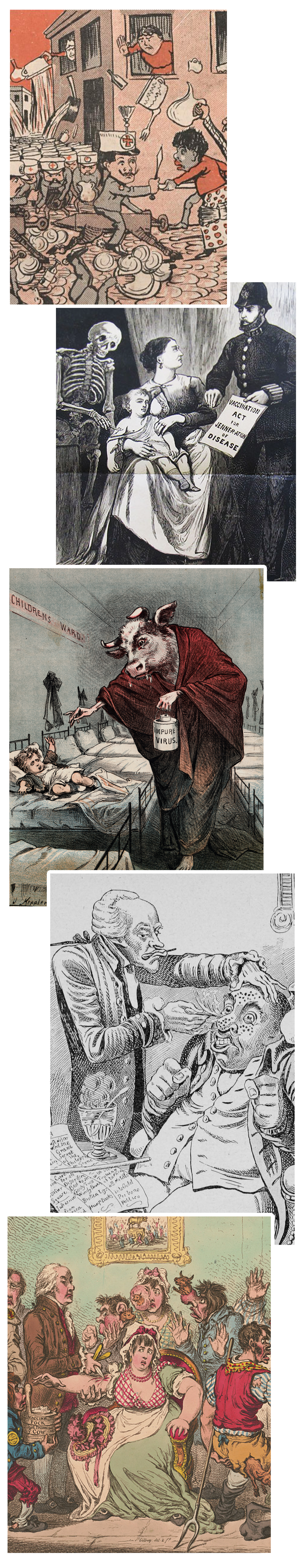

It is not trivial to override the core felt sense, in a democracy, that if anything is one’s own, it is one’s body. The idea of the state or a doctor performing a medical procedure forcibly on a person, or drugging them into compliance without their consent, is an abiding, terrifying theme of many science fiction dystopias, and it is a fear that runs very deep in the modern psyche. This fear runs deeper in some people than their fear of the virus, or losing their jobs or pensions, as we are seeing. History shows that these are not just fantasies: Past medical and public health abuses really did make use of forced injections of drugs, operations, sterilizations, and even psychiatric abuses—in totalitarian and democratic societies both.

Moreover, to say to the unvaccinated, “But it is in the name of the greater good!” is to make the utilitarian argument that we must strive for the most good for the greatest number of people. A version of utilitarianism is often the governing philosophy of public health. But this raises a series of questions: How are we measuring the good? Is it the same for all people? Should it be up to your 89-year-old grandmother, who has little time left, to decide whether to spend the remaining years of her life in total isolation, or risk COVID but see her loved ones? And the bigger questions: Can you explain how you are helping the group when, by overriding individual rights, you degrade the group as a whole by weakening each individual within it? Are you aware that the greatest evils in history have also always been done in the name of that abstraction, “the greater good”? Without first answering such questions, utilitarianism is but a shallow form of arithmetic, one passing itself off as moral philosophy.

It is not irrational for people to insist that public discourse seriously engage questions like these, and that any state compulsion related to people’s bodies be based on a flawless, air-tight argument that is well-communicated. That has not happened.

What, in rational political and public health terms, is the state’s best justification for mandating that people be injected en masse with a medicine?

The first justification for mandates is they get us to herd immunity faster. But as Stanford epidemiologist Jay Bhattacharya and Arizona State University economist Jonathan Ketcham note, “we have good reason to doubt that, if most everyone got vaccinated, we’d achieve herd immunity.” This is because, as we’ve seen, current vaccines are fading at about five months.

Even scientists who believe vaccines will help get us to herd immunity are divided on what percentage of the population needs to be vaccinated to get us there. Early in the pandemic, Fauci said we needed as low as 60%-70% to reach herd immunity, but as time went on he increased the numbers. In December 2020, when The New York Times noticed Fauci was “quietly shifting that number upward,” he explained he was generating these percentages based on a mix of the science and what he felt the public was ready to hear, admitting: “We really don’t know what the real number is.” President Biden recently said that we could need 98% of Americans to be vaccinated to reach the goal.

Is there a scientific consensus behind the 98% claim? In fact a number of epidemiologists and infectious disease experts and officials dispute that we need a number anywhere near it. Even those who are pro-mandate, like Dr. Monica Ghandi, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California San Francisco, believes that “There is no evidence that we need that high of a vaccination rate [98%] to get back to normal.” Other countries, like Denmark, have opted for a 74% vaccination rate as acceptable in order to lift certain restrictions, especially if the most vulnerable are vaccinated at a higher rate. Norway lifted all restrictions when it got to a 67% vaccination rate.

The point here is that the science is shifting, sometimes by the day. It is reasonable for people who notice this to feel concerned about it, and it is—at the very least—churlish to present them as merely irrational.

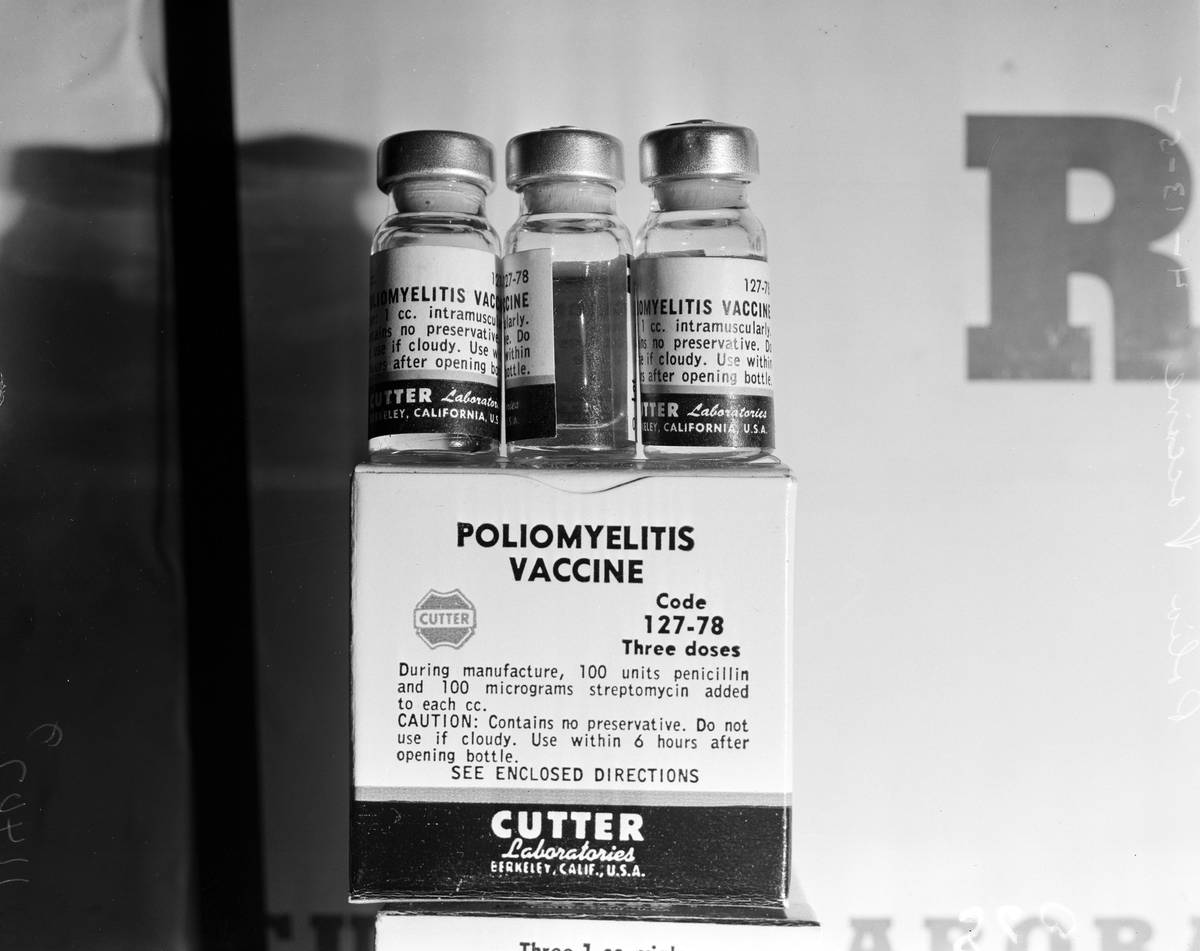

The second justification for mandates is that the state has an obligation to protect those who cannot protect themselves from an infectious disease passed on to them by others—i.e., the unvaccinated do not have “a right” to “recklessly endanger” and infect others. As many have pointed out, it is hard to describe our current moment quite this way, since vaccines, and now boosters, are freely and widely available, so people can protect themselves if they wish. Of course, this reveals the real problem, which is that vaccinated people do not, in fact, get comprehensive immunity—as in the case, for example, of the polio or measles vaccines.

And on this, there is increasing scientific agreement: We can’t “eradicate” this mutating virus at this point. It is likely not a case like smallpox, which was eradicated because both the virus and the vaccines met a host of criteria. Donald Ainslee Henderson, who directed the WHO smallpox eradication campaign, wrote that smallpox was uniquely suited for eradication because it didn’t exist in animal reservoirs, it was easy to identify cases in even the smallest villages by its distinctive awful rash (so a test for it wasn’t needed), the vaccine gave immunity that lasted a decade, and natural immunity was easy to identify by the scars smallpox left. COVID satisfies none of these conditions.

“If we are forced to choose a vaccine that gives only one year of protection,” said Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist also involved in smallpox elimination, “then we are doomed to have COVID become endemic, an infection that is always with us.” He and five other scientists have since argued together that COVID is not going away, because it’s growing in a dozen animal species, and variants allow it to pop up in places that once beat it back. (Indeed, this is the reason that some scientists argue we need over 90% of people vaccinated, to keep America safe from a virus that will pingpong around the unvaccinated parts of the globe for years.) As Brilliant and colleagues wrote recently: “Among humans, global herd immunity, once promoted as a singular solution, is unreachable.”

So, if it’s correct that we can’t eradicate the virus, and we can’t get a lasting vaccine-induced herd immunity, what is our goal? It would be, to use Monica Gandhi’s phrase, “to get back to normal.” It would mean accepting some natural herd immunity and putting more focus on saving lives by other means alongside vaccines—including better outpatient medications to catch COVID early and keep people out of the hospital; lowering our individual risk factors; and speeding delivery of vaccines to the highly vulnerable when an outbreak occurs, and prioritizing them over people who are already immune.

That the justifications originally given for mass public mandates are so weakened is one of COVID’s many unexpected challenges, one that requires flexible thinking, new kinds of planning, and above all acknowledgement, lest its denial becomes yet another example of bungled trust.

In tackling the trust problem generally, we can return to the two kinds of public health systems, the coercive and the participatory. The United States has all sorts of mandates, but also continues to have significantly high rates of vaccine hesitancy and vaccine avoidance. In contrast, Sweden is the leading example of a participatory public health model. “Sweden has one of the highest vaccination rates in the world, and the highest confidence in vaccines in the world. But there’s absolutely no mandate,” Kulldorff—again, one of the world’s leading epidemiologists, a specialist in vaccine safety, and consultant to the ACIP COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup—notes. “If you want to have high confidence in vaccines, it has to be voluntary …. If you force something on people, if you coerce somebody to do something, that can backfire. Public health has to be based on trust. If public health officials want the public to trust them, public health officials also have to trust the public.” Just as pharma’s indemnification removed its incentive to improve safety, so do mandates remove public health’s incentive to have better, more consistent communication—to listen, understand, educate, and persuade—which is what builds trust.

Kulldorff is echoed by Damania, who is by my estimate one of the most effective persuaders of the vaccine hesitant. “I’ve been so wrong in the past about things,” he noted, in one video:

I actually at one point in my career felt that shaming anti-vaxxers was a good idea because they were so dangerous to children. This was the pre-pandemic stuff, and it never works to convince anti-vaxxers. I would rarely ever get emails from people saying, ‘Hey I was on the fence and you convinced me with your crazy rant about how stupid anti-vaxxers are … Then I started to wake up a bit … Why is it people feel the way they do? And when you really dig into it, you go, I can empathize with that. Actually we share the same goal, which is our kids should be healthy, so, and you really think this is going to help, so of course you are going to, in fact I should love you for trying to do the right thing for your kids …

Indeed, demonizing people for having doubts is the worst move we can make, especially since there are serious problems in our drug and vaccine regulatory systems. Some health organizations have become concerned enough about the effects of non-transparency that a group has formed, made up of the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Transparency International, and the WHO Collaborating Centre (WHO CC) for Governance, Accountability, and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical Sector. In a report released recently, the alliance analyzed 86 registered clinical vaccine trials across 20 COVID vaccines, and found only 12% have made their protocols available as of May 2021. Scores of key decisions affecting the public were never made available. The U.S. government should immediately give the public and outside scientists access to raw data on which studies are based, and the minutes of meetings where major decisions are made on policies like mandates; we need the kinds of transparency Peter Doshi has asked for from pharma, and Kesselheim did from the FDA. Doshi and some colleagues from Oxford have asked, for instance, what the rationale was for the regulatory agencies to allow pharma companies not to choose hospitalization, death, or viral transmission as “endpoints” in the authorization studies. Let’s see the internal deliberations; let’s see the minutes of crucial meetings. All these researchers are doing is being true to the motto of the Royal Society, the first national scientific institution ever established: Nullias in verba, “Take Nobody’s Word For It.”

Acknowledging severe problems in regulatory agencies or within pharma doesn’t mean believing that everything that system produces is tainted, or that all the people in those institutions are corrupt. In fact, it defends those with the most integrity—because it is they who are most frustrated by a system that requires radical restructuring and new leadership. Even if—especially if—we think of ourselves as “pro-vaccine,” we should want to rescue this extraordinary technology from the flawed and broken system of poor regulation, insufficiently transparent testing, and manipulative messaging.

But many are choosing instead to replace this conversation about the system underlying the vaccine rollout with vaccine mandates—a strategy that troubles even some of those who have been very invested in the success of the vaccines.

“Right now with these vaccine mandates, and vaccine passports, this coercive thing is turning a lot of people away from vaccines, and not trusting them for very understandable reasons,” Kulldorff says. “Those who are pushing these vaccine mandates and vaccine passports—vaccine fanatics I would call them—to me they have done much more damage during this one year than the anti-vaxxers have done in two decades. I would even say that these vaccine fanatics, they are the biggest anti-vaxxers that we have right now.” Those congratulating the United States on mandates “working” conveniently leave out that each of those “wins” is potentially a recruit for a resentful army that does not believe in vaccines. Imagine a scenario—already unfolding in Israel—in which regular boosters are deemed necessary: How easy do you think it will be to drag those people into this action every six months? Wouldn’t it have been more effective to have enabled them to own these actions for themselves much earlier—thereby making it more likely that they would sustain them?

There are ways for all of us, medical professionals or not, to stop the bleeding, beginning with changing our orientation to those who are skeptical.

I have to return here to Damania, whose widely watched videos have attempted to persuade the hesitant to get vaccinated. “I love the coronavirus vaccines,” he has said. “They work, they save lives, they prevent severe disease. Immunity is our only way through a pandemic, whether it is naturally being infected or being vaccinated.” And yet he too believes that mandates are “going to set back the cause of vaccination and increase tribal division.”

Instead of coercion, he offers engagement. When a viewer (in the chat, or in a personal email to him) raises concerns, Damania doesn’t minimize it or go around the problems; he works through them. He addresses conflicting studies, bringing on some of the world’s finest epidemiologists and public health experts, and shows us the real world of physicians and scientists agreeing and disagreeing. He acknowledges when the science is not as airtight as officials present it. And he doesn’t use a one-size-fits-all approach, if he can avoid it: If a person raises a personal health issue—an allergy, or immune issue, or cardiac problem—he factors it in, and sometimes a person decides to get the shot. Sometimes they decide not to, and he wishes them well. As a result, people feel listened to, and in turn become more open to listening to what he has to say. Whether one agrees with his advice or not (I often agree, or come to agree, but not every time) his respectful approach seems to me irreproachable, and, to judge from the results, effective.

In addition to primary care physicians, those who are “pro-vaccine” (but not professionals) also have a role to play here, in acknowledging that some of their fellow citizens’ distrust is utterly warranted: The seemingly bottomless lining of pharmaceutical pockets; the unconscionable censorship of scientists; the grotesqueness of seeing the rich, unmasked at a Met Gala, waited on by a masked servant class; the downsides of and controversy around masking schoolchildren, and more. If they are not listened to when they are obviously right, why would they listen to others?

Some might come to the end of this essay and wonder why I—so cognizant of all the problems with the U.S. regulatory process and study transparency—got vaccinated.

I did so when I had time to think through my own situation, as many physician friends did. We knew that COVID was for many a beast not taken lightly. Like them, I used an individualized approach, which ideally everyone should be able to do with their own physicians if they have special health issues. For me, this meant taking into account how prevalent the virus was at the time in my area, its lethality and possible long-term effects in someone my own age, sex, with my own health history, and the probability of side effects known at the time, and my own response to vaccines in the past, and the fact that I had no allergies to the additives. There were transparency problems with the clinical trials, which meant there was a lot we did not know, but already by the time I got my own shot we did have some knowledge that the vaccines were lowering deaths. While factoring in my own risk tolerance, I tried not to pretend I knew more than I really did, about COVID or the vaccines.

Of course governments will not want to rely on a system in which everyone is encouraged to go to their physician for some kind of individualized discussion. But we are not talking about everyone here. We are talking about people who remain unconvinced, after our public health system has done its best at a mass-marketed vaccine campaign. It is a minority of citizens, but a sizable one. We can either choose, as we have, to coerce them with economic and social deprivation. Or we can work to better engage them.

For Tocqueville, “the tyranny of the majority over the minority” is the ever-present danger in democracies, the remedy for which, John Stuart Mill argued, was a protection of minority rights, and, above all, the right to continue speaking—even if a majority opinion seemed to be crystalizing. Mill in the end was influenced and changed by Tocqueville’s notion of the tyranny of the majority, and pointed out that the tyranny unique to democracy gave rise to “the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion” in the social sphere, in our so-called free societies. It moved him to write his great plea for free speech, in On Liberty:

Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling; against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them; to fetter the development, and, if possible, prevent the formation, of any individuality not in harmony with its ways, and compel all characters to fashion themselves upon the model of its own. There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence: and to find that limit, and maintain it against encroachment, is as indispensable to a good condition of human affairs, as protection against political despotism.

To find that limit and maintain it becomes the difficult but essential task when a plague besets a democracy—especially one that wishes to remain in good enough condition to survive it.

Return to Chapters I, II, or III. To download a free, printer-friendly version of the complete article, click here.

Norman Doidge, a contributing writer for Tablet, is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and author of The Brain That Changes Itself and The Brain’s Way of Healing.