The Science of Risk

Who knows best how to avoid harm?

The world is a risky place, and if you live there, you’re a full-time risk assessor. Should I have my brakes checked? Can I get away with calling in sick? Should I order the cheese fries or the broccoli? What could go wrong if I taste that forbidden fruit?

Many of those calculations take place beneath the surface, in the parts of our brain that don’t intrude on conscious thought. But novel problems tend to make us perk up, and right now we’re awash in novelty. Is it safe to go to the supermarket? Do I need to wear a mask? Is it safe to call a plumber?

It’s a new world too for policymakers, with decisions to make about lockdowns, school closings, masks, and the larger question of which decisions should be made by governments and which should be left to the individual.

The answers depend on the answer to another question: Are people generally any good at risk assessment? Depending on circumstances, the answer can be anywhere from an emphatic yes to an emphatic no. Science and history can help delineate those circumstances, before we return to the policy questions.

Start here:

Which of the following strikes you as more valuable?

1) A $50 gift certificate.

or

2) A lottery ticket, with a 50/50 chance to win. The prize is a $100 gift certificate. If you lose, the consolation prize is a $50 gift certificate.

Please tell me you consider this a no-brainer. Win or lose, the lottery can never turn out worse than the sure thing. Of course you should play the lottery!

But 60 University of Chicago students, participating in a laboratory experiment, appear to have thought otherwise. The median student offered to pay $25 for the gift certificate (which was near its expiration date and had a number of restrictions), but only $5 for the lottery ticket.

These students thereby placed themselves squarely in a long tradition of perverse behavior by experimental subjects. Here’s another experiment, this one devised by Daniel Ellsberg, a name that might be familiar to readers old enough to remember Watergate:

An urn contains 90 balls. Of these, 30 are red. Some are green, but I won’t tell you how many. The rest are some other color. Blindfolded, you get to draw one ball. Would you rather bet that the ball is red, or that the ball is green?

I trust that your choice will be guided by whatever you believe or guess or intuit about the contents of the urn. If you think there are more red balls, you’ll bet on red. If you think there are more greens, you’ll bet on green.

As it happens, most people go with red. That is, most people seem to believe the reds are likely to outnumber the greens, or at the very least that the greens don’t outnumber the reds. I’m not sure why they believe that, but I certainly have no problem with it.

Now let’s do a different experiment with the same urn. Once again you get to draw one ball. This time, would you rather bet against the ball being red or bet against the ball being green?

Most people choose to bet against red. Apparently they believe that the reds are outnumbered by the greens!

It’s fine to believe that the reds outnumber the greens, and fine to believe that the greens outnumber the reds. But when you’re able to believe both things at once, I start to worry about how you survive in the world.

Ellsberg surmised that no matter what you ask them, people always say “red” because they’ve been told the exact number of red balls, which somehow make them feel more secure. This might explain their choices, but it can’t excuse them. The obvious conclusion is the depressing one—that people in general are amazingly bad at risk assessment.

Not so fast, though. All these experiments can tell us is that laboratory subjects are often amazingly bad at risk assessment. But unlike most people most of the time, laboratory subjects share a key feature: Their choices don’t actually matter very much.

For example, those Chicago students were told there was a 95% chance that the gift certificates were imaginary and that no money would ever change hands (other than the $3 payment they received for showing up). And in Ellsberg’s case, 100% of the payoffs were imaginary. All he did was survey people about what they thought they would do if there was money on the table.

Perhaps all we’ve learned so far is that people respond frivolously when they’re 95% sure that their responses won’t matter, or when they’re playing with trivial amounts of money. When careful judgments are not rewarded, people don’t take the trouble to make careful judgments. That’s what a lot of us would call a rational response to incentives.

And so it goes even in experiments that have nothing to do with risk. At the University of Arizona, students chose to pay for the privilege of transferring money from one anonymous stranger to another! For every dollar you gave the experimenter, he’d take two more dollars from Stranger A and then give all three dollars to Stranger B (both of whom the students had never met and whose identities would never be revealed). The average student chose to hand over $3.63. How do you explain that? You could be tempted to infer that people just happen to love redistributing income for its own sake. (And this might help to explain some of the quirks in the U.S. tax code). But a more plausible moral is that we should be skeptical about extrapolating from the lab to real life.

Now: How do people do at assessing risk outside the lab? You can’t always tell by watching them, because you’re usually missing a lot of information about what those people are trying to accomplish and what obstacles they’re trying to overcome.

For example: In medieval England, in the Third World today, and in many times and places in between, subsistence farmers have tended to own several small strips of land scattered around their villages. They spend a lot of time traveling from one plot to another, which is time that could otherwise be spent planting or harvesting. With a little bit of trading, they could consolidate their holdings and improve their yields. So why don’t they trade?

One theory is that subsistence farmers are either not very bright or not very thoughtful. An alternative theory, advanced by the economic historian Deirdre McCloskey, is that the farmers are quite brightly and quite thoughtfully insuring themselves against localized disasters such as floods. If you live where there are no organized insurance markets, you don’t want to risk having all your holdings wiped out at once.

How should we decide which theory is right? Here’s a starting point: First investigate just how expensive this scattering is (in terms of forgone farm production). Then investigate how much risk the farmers are facing. Then ask whether the prices they’re implicitly paying for insurance are commensurate with the prices other people around the world are willing to pay for insurance against similar sized risks. Broadly speaking, the answer is yes.

When subsistence farmers face difficult trade-offs, they resolve them on the same terms that would appeal to a sophisticated Wall Street risk manager. If that’s not proof, it’s at least a strong reason to believe that when it comes to their own livelihoods, subsistence farmers are first-class risk assessors.

Another example: People who are very poor—most of them located in Africa and Asia—face heartbreaking trade-offs every day. One of those trade-offs is the choice between sending your children to do debilitating work in unsafe and unclean factories, or sending them to bed hungry. Either choice entails grave risks to your children’s health and development.

Affluent Westerners, confronted with photos of children in dire working conditions, sometimes jump to the conclusion that the parents are either poor decision-makers or have been co-opted, coerced and/or manipulated by unscrupulous employers. But history tells a different story. In the parts of the world where 21st-century child labor is common, people are roughly as poor as Americans in the year 1840—and they send their children to work at about the same rate as those Americans. In 19th-century America, as incomes rose, parents pulled their children out of the labor force. In the 21st-century Third World, as incomes rise, parents are pulling their children out of the labor force at about the same rates and at about the same threshold incomes as 19th-century Americans, Europeans, and others around the world.

The natural conclusion is that certain amounts of child labor are something like a universal response to certain levels of poverty—just as you’d expect if parents everywhere make the same careful calculations.

People are always doing things that seem mysterious. So why might we trust that they generally make good choices?

First there’s the sort of evidence we’ve just seen: Different people, living in different times, different places and different cultures, but confronted with similar risks, tend to make similar choices. At a minimum, that suggests that they’re not choosing randomly.

But there’s also another kind of evidence: When circumstances change, people generally change their behavior in ways that make sense. When the price of chicken rises, people buy less chicken. When asbestos turns out to be deadly, people use less asbestos. There is a vast academic literature testing these and similar propositions, leaving no doubt that people respond in the expected way to changes in the price and/or known health consequences of soft drinks, cannabis, bus travel, car travel, airline travel, haircuts, every sort of foodstuff you can imagine, cigarettes, alcohol, education, cellular data, health care, and legal services.

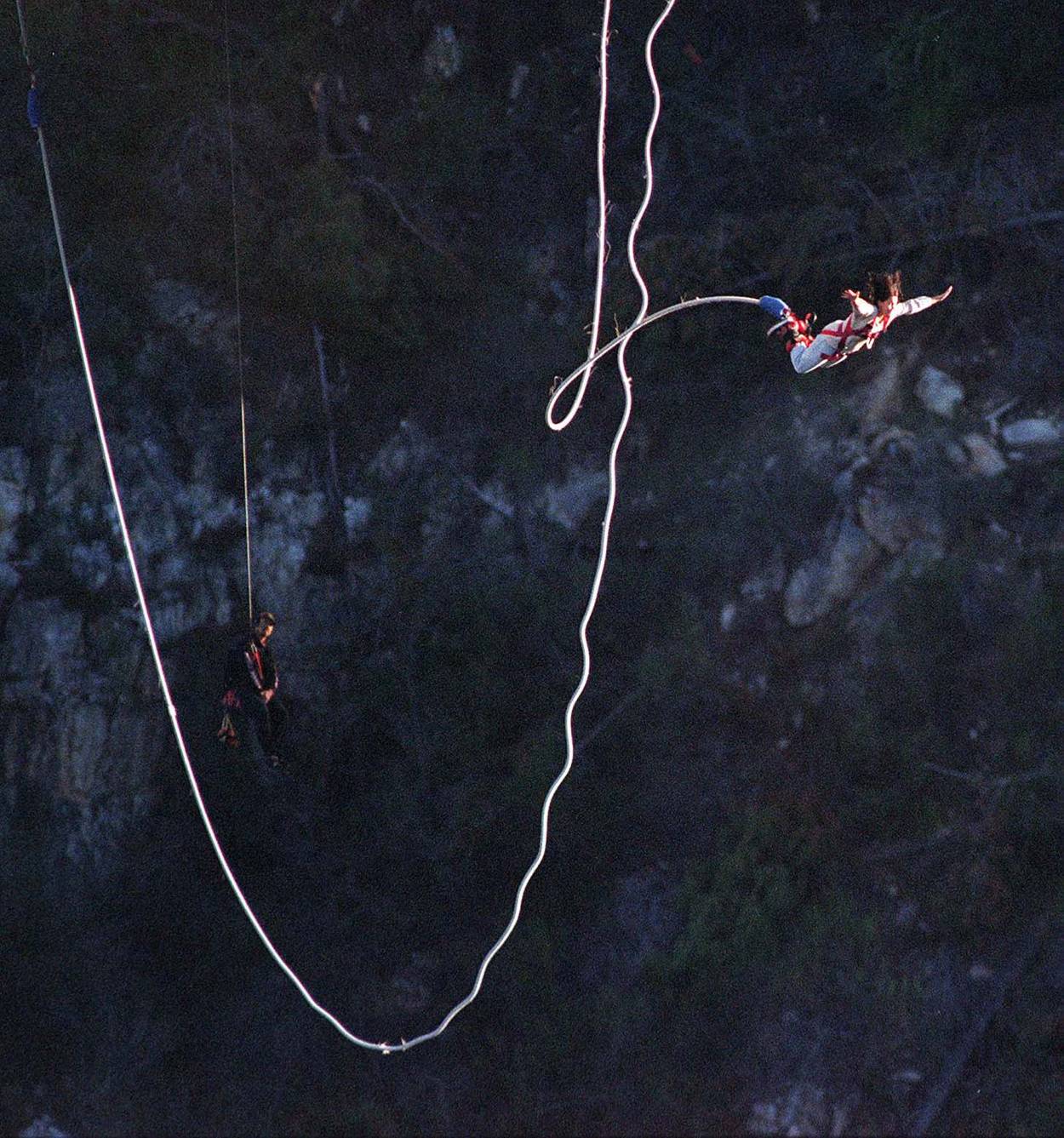

In 2001, following the crash that killed legendary race car driver Dale Earnhardt Sr., NASCAR mandated that all drivers wear a head and neck restraining system which affords considerable protection in the event of a crash. NASCAR drivers responded by driving, on average, about 2% faster.

Should one worker die so that, say, 15 million people can have cheaper hamburgers?

Every day, drivers trade off the risk of a fiery crash versus the risk of losing the race. Do they choose wisely and deliberately? You and I can’t answer that question by observing their choices on a single day, because we know too little about the terms of the trade-off. But when we observe the choices both before and after the NASCAR authorities change the terms of that trade-off, we can test the proposition that the choices are wise—and the results of that test look pretty good.

You might object that NASCAR drivers are a breed apart, and that it would be rash to generalize from them to people in general. But people in general behave the same way. Your grandfather’s (or, depending on your age, maybe your great-grandfather’s) family car had no seat belts, no shoulder harnesses, no padded dashboard, no collapsible steering wheel. Your father’s had no traction control or anti-lock braking system. Your own, until recently, had no blind spot monitor or active lane control. And nearly every time one of these safety devices was added, people in general started driving faster. (I said “nearly every” instead of “every” because there might be one or two that haven’t been carefully studied.) People trade off the risk of a crash against the risk of being late for dinner, and when the terms of the trade-off change, they change their behavior, just as you’d expect from wise and deliberate risk assessors.

One more example: Prior to the late 19th century, formal education was expensive enough to be a poor investment, and most people chose not to educate their children. (Jews were an exception, probably because education—at least sufficient education so that you could read the Torah twice a week—was required by their religion.) But with the Industrial Revolution, knowledge became far more valuable, and a great asset on the job market. Families responded by sending their kids to school. To afford that schooling, they also chose to have fewer kids. In the 1860s, the average Englishwoman had six or seven children. Fifty years later, she had two or three.

That’s particularly striking in view of the apparently widespread belief that before modern birth control, children were something that just happened to people, rather than the products of deliberate choice. In fact, family sizes have always responded delicately to changes in economic conditions.

All of that is evidence that people assess risk pretty well and act accordingly. But here is the evidence most relevant to the age of COVID-19, all of it gleaned from multiple studies:

The typical American is willing to pay up to about $1,000 for an auto safety device that has a 0.0001 chance of someday saving the driver’s life. (Actually a bit less than $1,000, but I’m rounding up.) The typical construction worker, asked to take on riskier work that increases his annual probability of death by 0.0001, will require an annual raise of about $1,000. If your home is located near a Superfund site with a 0.0001 probability that toxic waste will eventually kill the homeowner, you’ll find that your property value is depressed by about $1,000. Americans who pay out-of-pocket for visits to health care clinics will typically shell out up to about $1,000 for a treatment that has a 0.0001 probability of saving their lives.

(For small probabilities, these numbers scale in the obvious simple way—change the probability to 0.0002 and the willingness to pay changes to $2,000. For larger probabilities, there is no simple scaling rule, nor is there any reason why there should be. In other countries, the numbers tend to be different but equally consistent, and can be pretty accurately predicted on the basis of income.)

The $1,000 number, by itself, tells us nothing whatsoever about whether people are rational and reasonable. A perfectly rational, reasonable person might be willing to pay up to $2,000, $3,000 or $10,000 for the peace of mind that comes with that auto safety device. Another equally rational and reasonable person, endowed by nature or nurture with a bit more risk tolerance, might balk at anything over $500.

But if an auto safety device and a medical procedure contribute equally to life expectancy, then no rational and reasonable person would be willing to pay more for one than the other (unless, for example, the medical procedure has additional benefits, but the relevant data control for such things). That would be as ditzy as offering to pay more for a gift certificate than for a lottery ticket with the same gift certificate as a consolation prize.

The good news, then, is that people are not that sort of ditzy. Broadly speaking, they’re willing to pay the same amount to avoid a given risk, regardless of how that risk arises. Unlike laboratory subjects, real people facing real problems in the real world appear to do a pretty good job (consciously or not) of assessing risk, weighing costs against benefits, and making choices that advance their goals.

In the lab, with nothing at stake, people make poor choices. In the marketplace, with their safety and livelihoods on the line, they do pretty well. How do they do in the voting booth?

The voting booth is like the lab: It doesn’t make a bit of difference what you do in there. In nearly any election, the probability that you (or anyone) will cast the deciding vote is effectively zero. If you had never voted in a presidential election, the same guys would still have won every time.

If people are smart enough to weigh the costs and benefits of safety devices, occupational choices and medical interventions, then they’re smart enough to weigh the costs and benefits of educating themselves about issues they can’t affect. If you want to be good at voting, you’ll have to master the arcana of competing tax policies. If you want to be good at life, you’re probably better advised to binge-watch The Simpsons. People generally—and wisely—choose the latter.

Hence the sorry state of public discourse, which is so widely recognized that I’ll resist the temptation to document it with a long list of egregious examples.

That’s a good reason to be wary of giving too much power to elected officials, who are chosen by poorly informed and foggy-minded voters and then either rewarded or punished for their performance by those same voters, leaving them sorely underincentivized to be either wise or benevolent. When it’s possible, we get better outcomes if people can make their own individual choices and live with the consequences.

Now let’s talk about COVID-19. How should our communities make decisions about lockdowns, closings, masking, and other public health measures?

Start with social distancing. In order to protect yourself (we’ll get to protecting others in a moment), should you stay completely out of the grocery stores and off the hiking paths, or just adopt judicious policies about not getting too close to people? What, exactly, should those policies be? If there’s a problem with your garbage disposal, should you call a repairman? Can you and some friends form a “pod,” interacting with each other (and only with each other) as if times were normal? How big a pod? How do you vet the members?

There can be no one-size-fits-all answer to these questions. Some of us are a bit more or less risk-tolerant than others. Some need hugs a lot more than others do. Some have healthier immune systems, or are less at risk because of their age or health status. Some live with elderly parents; some live alone. You and you alone are equipped to evaluate your highly personalized bundle of costs and benefits—and because that’s the kind of thing people are generally good at, I believe you’ll make a choice that serves you well.

In other words, I trust you to take care of yourself. But that’s not the end of the story, because you’re not the only person I care about. What about the decision to wear a surgical mask, which is mostly for the benefit of others? Who will protect, for example, your fellow grocery shoppers?

That’s easy: The owner of the grocery. If grocers are allowed to set their own mask policies, then some will cater to customers who prefer more comfort and others to customers who prefer more safety. If the majority of customers want mask-mandatory environments, the majority of groceries will offer those environments, while others cater to the niche market of those who prefer to go mask-free. Insofar as you’re worried about transmission inside a place of business, there is still no need for government mandates.

But that’s still not good enough. What about people you encounter on the street or on the subway after shopping in the mask-free grocery—and the people they pass in the street the next day—and the rescue workers who will attend to those people if they crash their cars next week? Who’s looking out for them? You might well argue that it can only be the government.

This provides a good argument for government mandates, but there are multiple reasons why it’s not necessarily a compelling argument. First, a policy of laissez faire allows different people to make different choices appropriate to their own circumstances and preferences. When everyone’s required to do the same thing, we lose all that. Second, you don’t need mandates insofar as you believe the main problem is transmission in stores, bars and restaurants, where owners are fully incentivized to look out for their customers’ interests. And third, governments are generally pretty bad at the things they do, partly because voters are generally pretty bad at choosing governments.

All of the above applies also to closings. In New York state, where I live, all nail salons have been deemed “nonessential” and have therefore been closed by fiat. I do not believe that my governor has any way of knowing how desperate I am for a manicure, or what risks I’m happy to take in order to get one. I am sure that if the nail salons were open, they’d find ways to protect their customers up to the limits of what the customers want, and that some customers would still choose to stay away. I believe that might be a pretty good way to run things. I also believe that if we did run things that way, some people would get infected in nail salons and then pass on their infections to others who would then infect additional strangers. That would be bad. It might (or might not!) be something we’d want to tolerate, just as we tolerate the existence of cars, ovens and prescription drugs that are virtually guaranteed to kill a certain number of people every year. On balance, I don’t believe I have enough information to know whether the nail salons should be open. I hope on this issue that my governor is better informed and wiser than I am—but I’m not sure we can count on that.

Imagine a lockdown policy that’s expected to save 30,000 randomly chosen American lives. How do we determine if that policy is worth adopting?

As a fraction of the American population, 30,000 lives is about 0.0001. That means this policy has a 0.0001 probability of saving your life. What are you willing to pay for that?

Presumably the same amount you’d be willing to pay for an auto safety device that has a 0.0001 probability of saving your life. If you’re a typical American, as we’ve already noted that’s about $1,000.

That means you’ll want this policy implemented if it costs you, personally, less than $1,000. A policy that costs each American $1,000 costs the nation a total of about $300 billion. So on the principle that the government should give the people what they want, this is a good policy if (and only if) it reduces national income by less than $300 billion.

Likewise, for a policy expected to save 60,000 lives, we should be willing to sacrifice up to $600 billion. And also likewise, for a policy expected to save one life (which means a probability of about 0.0000000033 that it will save your life), we should be willing to sacrifice up to 3.3 cents per American, or $10 million altogether. (This is exactly what economists mean when they say that in the United States, the value of a life is about $10 million.)

The number will change as Americans get richer. The Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968 killed 100,000 Americans, but there were no calls for lockdowns. Undoubtedly part of the reason is that Americans were much poorer then, and when you’re poorer, you’re not willing to pay quite so much for risk avoidance. More precisely, the average American income in 1968 was about 40% of what it is today. According to various estimates, this probably meant that the value of a life was only about $6 million back then.

There are legitimate reasons to be a little squeamish about this argument. For one thing, the calculation I’ve described relies on the preferences of the typical or average American, and not all of us are typical or average. Some are willing to pay a bit more for safety and some a bit less. But that’s the kind of problem you simply can’t avoid when decisions are made collectively. Because preferences differ it’s impossible to satisfy everyone’s preferences with a policy that applies to everyone. You do the best you can, and the best you can do is to value a life at about $10 million.

So how are we doing? It’s hard to tell, because nobody yet knows how much the lockdowns have cost and nobody may ever know how many lives they’ve saved. But just to get a sense of things, let’s take a ballpark guess that the lockdowns have cost us, on average, about a half-year’s income—that is, about $30,000 per person. That’s a total of about $10 trillion, which, at $10 million per life, is about a million lives. If the lockdowns have saved at least that many lives—and if there was no cheaper way to accomplish the same thing—then the lockdowns have been worth it. If not, not.

Or, if you believe the lockdowns will end up costing us a full year’s income, they’ll have to save 2 million lives to have been worthwhile.

Again, there’s so much uncertainty about the costs and the number of lives saved that it’s impossible to tell whether we’re hitting those targets. But at least it’s clear what we should be aiming for.

If you happen to find yourself in charge of public policy for the next pandemic, it will be helpful to keep those calculations in mind. It will also be helpful to remember that people are pretty good at personal risk assessment, that they will always know more about their own priorities than you do, and that not every problem requires a centralized solution.

Finally, here are some things that are not helpful:

It is not helpful to pretend, like my governor, Andrew Cuomo, that, “The cost of a human life is priceless, period.” Fortunately, the governor doesn’t mean it. Household painkillers are responsible for a handful of deaths every year. If the governor thought that lives are priceless, he’d have to ban aspirin—not to mention cars, trains, horses, campfires, swimming pools, and matches. (Please don’t mention this to the governor; I don’t want to give him any ideas.)

If we treat lives as priceless, life will not be worth living. Fortunately, nobody has ever attempted to treat life as priceless, not even Gov. Cuomo, who is slowly allowing businesses to reopen.

Observing that lives have a finite price is the easy part. Identifying that price is the hard part. Fortunately, economists have done the hard work of estimating the price, though there’s room for quibbling around the edges. Roughly, it’s $10 million.

It would be good to have some thoughtful public discussion about whether the number should be a little higher or a little lower—in other words, whether the lockdowns should be a little less strict or a little more so. Cuomo, though, is not interested in that discussion. Instead, he degrades public discourse when he maintains both falsely and ludicrously that, “Our reopening plan doesn’t have a trade-off.” That a politician can say such things and still be taken seriously is one more confirmation that people behave frivolously in the voting booth.

It is not helpful to attack straw men, as did Joe Biden, with his sanctimonious declaration that, “No worker’s life is worth me getting a cheaper hamburger.” Absolutely nobody has ever suggested that any worker should die so that Joe Biden, or anyone else, can get a cheaper hamburger. The hard issue is: Should one worker die so that, say, 15 million people can have cheaper hamburgers?

If you think the answer to that one is obviously no, then you haven’t been paying attention to the world around you. Workers die in industrial and agricultural accidents all the time. Workers die so that large numbers of people can have cheaper breakfast cereals, cheaper cars, and, yes, cheaper hamburgers—and this has been going on since long before COVID-19. The important question is not “Is this OK?” because everyone agrees that it’s okay, except when they’re posturing. The important question—the critical question if you’re managing a pandemic—is, “How many people will have to get cheaper hamburgers for us to accept one additional death?” By diverting our attention to the nonquestion, Mr. Biden asks us to ignore what really matters.

It is not helpful to ignore reality, like President Donald Trump, who believed the pandemic would be over by Easter because he had a “good feeling” and continues to peddle quack nostrums. I can’t believe I have to mention this, but the height of a pandemic is a really really good time to listen to the scientists.

At the same time, it is not helpful to pretend that science has all the answers. Medical scientists know a lot about how to save lives. They have no special expertise on how many lives are worth saving. If the doctors tell us that closing all the supermarkets will save a million lives, we should take them seriously. But that doesn’t resolve the question of whether we should close all the supermarkets. That requires a discussion that can only be subverted by the sort of claptrap that Cuomo, Biden, and Trump are all peddling.

It is not helpful to deny that people’s priorities can legitimately differ—and that my failure to share your priorities does not make me a bad person. Some consider manicures essential; some consider them frivolous. If the government is going to issue mandates that apply to all nail salons, some people are going to be satisfied and others are going to be annoyed. That’s a good reason to stand up and be counted, but it’s not a good reason to hate your neighbor.

We’re all in this together. We sometimes differ about how to handle it. Thoughtful dialogue, informed by both science and economics, can help us understand and resolve some of those differences and make better decisions. Claptrap is the enemy.

Steven Landsburg is professor of economics at the University of Rochester and the author of Can You Outsmart an Economist.