The Greatest Short Jewish Tennis Player in the World

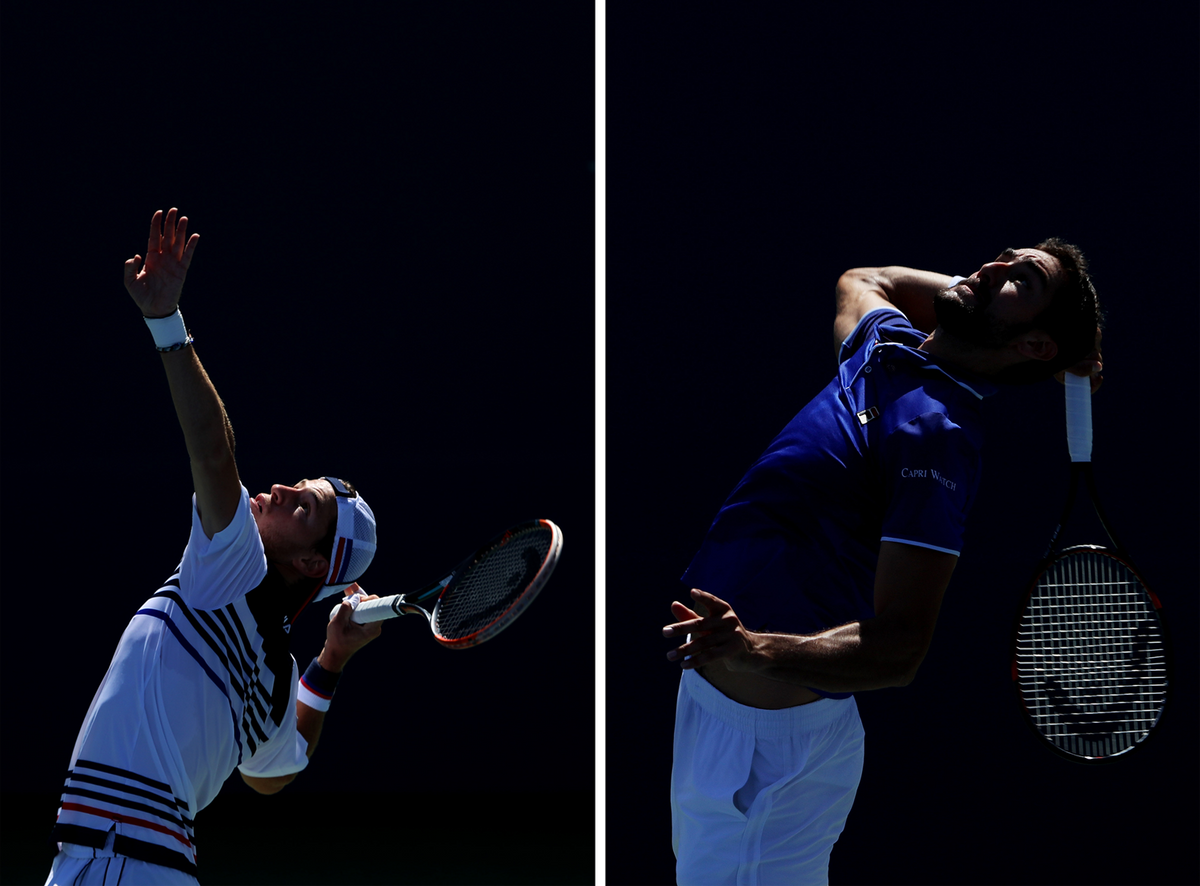

Diego Schwartzman and those who love him on the thrill and heartbreak of the US Open and Argentina

Early on the morning of Aug. 17, the Argentine Jewish tennis ace Diego Schwartzman, known for his tireless play and backward-baseball-cap-wearing acrobatic flair, celebrated the start of his 30th year on a family Zoom that lasted until 3 a.m. Buenos Aires time, 2 a.m. in Cincinnati. There was a chocolate cake, candles, and a soda pop toast. A few hours earlier, on Aug. 16, his birthday, he had completed a great comeback against the Russian Aslan Karatsev, winning 7-6 (7-3), 3-6, 6-2. It was the second year his birthday had found him in the state of Ohio, in the American Midwest: Strange surroundings for an Argentine immersed in solitude and distance, two feelings he has lived with during a life consecrated to tennis.

Birthday number 30 had a precise effect on him: It finally chased away the idea of eternal youth. “I’m now closer to retirement than to being young again,” he told me in a hotel bar on Lexington and 48th Street in New York City, where he’s staying to play in the US Open. He says he even has a number in mind for when he will stop playing professional tennis: 33. He ordered a lemonade, no sugar. Around us was the buzz ahead of the US Open, of players coming and going to training sessions in Queens, of managers, acquaintances, and friends in the sandbox of results and expectations, sharing the latest tour gossip. In his past 12 matches, Diego has won five and lost seven.

As we warm to our conversation, a man pounces on Diego and asks him for a photo, telling him that he had followed him to tournaments in Europe and the United States and that he saw him as a brother. The man confessed to being stimulated by a number of martinis, which gave him the courage to ask if Diego also enjoyed the cocktail. Schwartzman answered that he only likes Fernet-Branca, a northern Italian aperitivo that is popular in Argentina.

After the man leaves, Schwartzman allows himself to talk about the sport he loves the most: “Tennis is my job, but fútbol is what I like best,” he says. He played midfielder as a child, but he doesn’t play now, because the risk of injury is too great for a professional tennis player. Once he retires, he anticipates playing all the soccer that he couldn’t in his 12 years of life on a tennis court.

Schwartzman has become a realist about his own expectations for the US Open. His goal is to get to the second week, the round of 16. He speaks of the cruelty of tennis using a metaphor from martial arts: “You have one, two bad months, they give you a back-kick, and nobody steps in to defend the place you held for five years.”

On Feb. 18, 2013, a friend told me that I had to meet the future of Argentine tennis. The Buenos Aires Open, South America’s most prestigious tournament, was on. My friend was particularly short, and wanted to show the world what people his size were capable of.

The sun was shining on the Palermo neighborhood that day. I arrived to Guillermo Vilas Court, the clay court of the main stadium in the Buenos Aires Lawn Tennis Club, bringing my 2-year-old son in a stroller. Diego excelled for his height and for his strategies of chess-playing endurance: He could sustain long points until exasperating his rival. That day, Peque, as Schwartzman is known, then ranked 166th, won in the first round against the Brazilian Thomaz Bellucci, ranked 38th, 6-4, 4-6, 6-1. Diego was 20.

I saw him play again, years later, on a day of consecration, in February 2021, when he won the ATP Buenos Aires. In the final he crushed Francisco Cerundolo, six years his junior, 6-1, 6-2. Ranked ninth in the world, it was the fourth tournament win in Schwartzman’s career and his first in his home country. “Last week”—after losing in a tournament in Cordoba, Argentina—“I thought I was the worst person in the country, and now I am very emotional and happy,” he proclaimed. “Ever since I was a kid I would come see this tournament, to watch my coach play. To win it makes me proud.”

Born in 1979 in Ciudad Evita, in Buenos Aires, Peque’s coach, Juan Ignacio Chela, reached 14th in the world in 2011 and won six tournaments, two more than Peque has won to date. He retired from tennis in 2012 to become an analyst on TV, and stayed retired until 2016, when he started training Diego. At first they worked together eight to 10 weeks a year. Chela recognized a lot of himself in his protégé. “He’s attentive to detail: tennis, the physical preparation, rest, his grip, how to wield the racket. His small size was something I considered when he called me. Until I got to know him and his virtues, his technique, his way of thinking. We always worked on the tactical side to improve his potential, learning to play 10 balls a point, without a winner, but with intentions that orient the game.”

Diego travels with a trainer—Chela or Alejandro Fabbri—and a physical therapist. When practicing he normally does two exercise sessions a day, each of three-and-a-half hours, and one long tennis session of two-and-a-half hours. Preparing for the US Open, like for all Grand Slam events, includes not playing the week before, resting more than usual to handle the demands of five-set matches. The day before the competition he plays only 45 minutes. Once the schedule is released, he watches video with Chela and they start studying their rivals: How they play important moments in the match, how they approach tiebreaks. The night before, they build the game plan. “The pressure in New York is huge,” Chela says. “One good Grand Slam can change your year.”

In August 1992, Silvana and Ricardo Schwartzman decided, like many Argentine couples of that time, that their new baby boy would be called Diego, after Diego Armando Maradona. The soccer player had been a key part of the national team’s World Cup win in Mexico City in 1986, and again as runners-up in Italy in 1990, becoming the central figure of the national religion of the country.

In 1994, when the fourth Schwartzman child was 2 years old, Maradona tested positive for doping in the U.S. World Cup and was suspended. A few hours after the news broke, the soccer star dropped an indelible phrase, even in a storied career of sporting achievement, dramatic moments, and famous sayings: “They cut off my legs,” he said. That doping case, and above all an addiction to cocaine, affected his career and accelerated his retirement from soccer, which came in October of 1997. But as a tennis fan, and a fan of any sport where Argentina was competing, Maradona would show up at all the Davis Cup matches, where he’d unfurl his histrionics and euphoria on behalf of his country.

Maradona died on Nov. 25, 2020, shortly after his 60th birthday. Diego Schwartzman was already 28, and summiting the high point of his career: In the ATP Masters in Rome, in his first Masters final, he beat Rafael Nadal for the first time. On Oct. 12, 2020, he reached No. 8 in the world rankings.

In Maradona’s last years, the two Diegos formed a friendship made of WhatsApp and audio messages. The former soccer star would write after matches that the tennis star had lost. When he lost to Nadal at Roland Garros in 2020, Maradona said: “Copy everything you can from the best, but not their limits. Every person is unique.”

Part of the bond between the Diegos came from their diminutive stature: Maradona stood 5-foot-5 and Schwartzman is 5-foot-7. An exceptional and extraordinary talent, Maradona debuted in first division at 16 years old, and had for years before that inspired trainers and recruiters to predict a luminous destiny. The young Schwartzman, on the other hand, was hardly assured of success. For years, he toiled among the peloton of very good tennis players, without expectations of more. He was short, and would never grow taller.

At 13, the Schwartzmans commissioned medical studies to determine how tall Diego might grow to, and one estimated that he would be 5-foot-5, maybe 5-foot-5 ½. His parents were opposed to growth treatments, using injections and hormones, similar to what an Argentine soccer player who had just debuted with Barcelona was doing. His name was Lionel Messi, now considered one of the game’s all-time greats. Messi is 5-foot-7.

Currently ranked 16th in the world, Schwartzman is an anomaly in a sport that has become ever more physical. On average, his rivals have 6 inches on him, plus the added muscle that goes with larger body mass. His nickname, Peque, is diminutive: The Little One in Spanish.

"Peque” the name had nothing to do with his size, however—it was something he picked up as the youngest of four children. And the singularity of a small person reaching far beyond what his height might suggest of him has never really moved him. “When I enter onto a tennis court, I don’t think about how tall I am or how much bigger my opponent is. But if I were 4 to 6 inches taller, I might have a stronger serve or could hit with more power.” He adds: “I did want to be tall when I was a kid, but not because of tennis.”

Schwartzman is the shortest player in the top 100 as well as the highest-ranking Argentine on the tour; he is also the highest-ranking Jew. He proudly assumes both identities: Argentine and Jewish. He is also proud of being a player from the periphery, who competes against giants in places like London, Paris, Madrid, and New York. Tennis’s main circuit remains in Europe, and Peque lives in the far south of the Americas, from where he must travel farther than many other players. This too has both physical and mental costs.

Since 1853, when the Republic of Argentina adopted a political constitution modeled on U.S. federalism and liberalism from 1787, it became a country of immigrants. A local cliché serves to explain the demographics that resulted: Argentines are descended from boats, not from Incas or Aztecs like the Peruvians or Mexicans. Jewish organizations in Europe that coordinated with Argentine authorities to move large groups of people were highly successful in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, Argentina has the largest Jewish community in Latin America and the fifth largest in the world outside of Israel.

Diego’s maternal great-grandfather, Abraham Tuchsznaider, who joined that community, was born in 1900 in what is now Poland. He fought in the First World War. Before 1918, the train taking him and his regiment to the front derailed. Soldiers died or were wounded; some, like Peque’s grandfather’s father, abandoned the column and deserted. In the chaos of that incident, Abraham found an identification document for one Moises Naselzky. After days of trekking, he found his way to a boat at a seaport.

According to Sebastián Torok in an article published in La Nacion, it is believed that Abraham arrived in 1921 and stayed in a temporary Immigrant Hotel, where he was quarantined along with other third-class passengers entering Buenos Aires. Once in the Argentine capital, he managed to set himself up in Villa Crespo, not far from the geographical center of the city. Two years later, he was reunited with his wife, Sara (who entered Argentina under her maiden name Buchbinder) and his daughter Olga. They had three more daughters: Aida, Julia, and Celia. Celia married Mauricio Daiez and had three daughters. One was Silvana, Peque’s mother. The family’s fabric factory burned down. Financial difficulties led to Mauricio’s depression, which overcame him. His wife Celia lifted the family out of misery. “Chiche,” as she was known, sold sheets door-to-door. She then made and sold clothes with an aunt.

The Schwartzmans keep the family history in an unpublished book (The History of a Family by Gregorio Schwartzman) and through oral tradition. According to the latter, from what Luis Schwartzman told me from Paraguay, the family holds that in the mid-19th century, when Russian authorities started requiring last names, Jews chose descriptive monikers. Theirs chose Schwartzmann, which in Yiddish means the black(-suited) ones. The first-mentioned in the genealogical tree, Jaim Schvartzman, was born in Obodivka, Ukraine, around 1856. A part of the family arrived in Buenos Aires by ship in 1908 and started to diversify: Some went to the Jewish colonies of Entre Rios, Argentina, and another branch went to Paraguay. In August of 1921, Isaac Schwartzman was born in Buenos Aires. With his wife, Isabel Lips, born in Villa Angela, Entre Rios, they had two children and made their living making coat hangers for wholesale. The younger of the two is Ricardo, the father of the tennis player.

The Club Nautico Hacoaj was the first, most important, and the strongest connection Diego had with the Jewish collective in Argentina. Jewish social and sporting clubs like Hacoaj were fundamental to the immigrants’ adaptation to the world of work and manufacturing in their new trans-Atlantic homeland.

Hacoaj, the most modern of the 19th-century clubs, owes its name to the Tigre River delta and a group of 20 Jewish rowers who were rejected from a traditional rowing club in 1935. It was founded as the Club Nautico Israelita. Later, a group of members voted for the new name Club Nautico Hacoaj, in honor of the Hakoah of Vienna, which was destroyed by the Nazis when they took the Austrian capital.

Hacoaj today has 8,000 members (1,000 of whom play tennis), 21 sports, and five locations (four in Tigre and one in Buenos Aires). The most popular sports are field hockey and soccer. There have been Olympic rowers, and one soccer player selected for the national squad, Daniel Brailovsky. Players have come out of the club to represent Las Leonas, the women’s National Field Hockey team.

Ten days before the start of the US Open, I drove north from the capital to Tigre, a suburb where one of the Hacoaj’s branches is located. The Parana River forms a confluence there with tributaries that spill into the River Plate and a giant delta island, like that of the Nile in Egypt.

I was met there by Alejandro de la Rua, alias Nano, the tennis coordinator for the last 37 years. He was just back from Israel, where he had attended his first Maccabee Games.

We have coffee in his office, from which we could see the recently inaugurated Central Court Diego “Peque” Schwartzman. Twenty years ago there was a backboard there. “I remember,” Nano says, “seeing Peque every weekend hitting against that wall. It was striking because he was so small. For his body type he didn’t hit hard, he could not drive the ball nor stroke a powerful backhand, and he volleyed well even though he was short at the net. His principal virtue was his steady hand, and above all a prodigious mind. Very intelligent, hardworking, with a winning mentality, very brave. But he had an X factor that you couldn’t see. There are many filters that separate players. I remember him living to ask questions.”

Nano tells stories of the players that were way ahead of Peque. Players like Agustin Bellotti, who won the Junior French Open in 2010 and was projected to go much further, but who never went above 166th, back in 2013. No one from that generation made it to the top 100. He told me about one player who was No. 1 at ages 12 and 14, with a bright future. But he was all talent, and at 16 he lost interest. “Where is he now?” I asked. “He has a fabric company in Once”—a traditionally Jewish shopping area of Buenos Aires. Peque’s legend grows in comparison.

A banner beside that new central court has Schwartzman’s bio. “Born and raised in Hacoaj. Top 10 in world tennis (2020). Olympic athlete. Argentinian Davis Cup player. Talent, perseverance, Jewish values, humility. Symbol and pride of Hacoaj.” The honoree attended the inauguration in December of 2021. “It was a little strange to have a court named after me, especially for me as I’m fairly introverted, and try not to show too much,” Diego said. “But from age 7 to 14 I would come every weekend to Hacoaj with my parents. It’s where I first picked up a racket.”

Peque played interclub leagues for Hacoaj, competitions with two singles matches and one doubles for teams of four in each category. Peque won two. He occasionally heard antisemitic comments there. Ricardo got into a fight with another parent from a rival club, Gimnasia Esgrima de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Fencing Gym), when he heard “he had to be Jewish.” Hacoaj is not a religious club and is not closed on the Sabbath. Most of its members are not observant.

Nano showed me around that sunny Saturday. There’s a replica of the statue of David, and the club’s slogan is painted everywhere: Live in Happiness. There were paddleball courts, a subaquatic hockey pool, rowers out practicing without boats or oars. The river was low and gave off an odor. We passed the Tarbut Kinder and the first and second grades of the ORT, two of the schools Hacoaj runs onsite. In Tigre, Hacoaj also has a country club, an island, and a marina, as well as gated residences, new buildings, and bungalows as part of a real estate development. “Members have plenty of means, which makes them demanding,” Nano explains. Peque’s family are no longer members.

On Aug. 11 of this year, the Argentine government announced that the July inflation rate had reached 7.4%, the highest in 20 years. At the time, talk in mainstream Argentine media was all about an article in The New York Times that invited its readers to compare the United States with Argentina: “Think 9% Inflation Is Bad? Try 90%.” In reality, that 90% could be more like 100%. That Thursday, toward the end of the afternoon, Silvana Schwartzman, Diego’s mother, told me she knew Argentina’s successive economic crises intimately. “When Diego was born in 1992, we had exhausted everything: We literally had nothing to eat,” she told me.

Before Argentina’s string of economic crises began, the Schwartzmans, with her husband Ricardo at the head, had run a successful business called Vainilla, which had 20 employees making women’s accessories like bracelets, hoops, and barrettes. Ricardo would bring back merch samples from trips to the United States and Europe, and organize their production and sales. He diversified into another successful business in licensing Batman products.

While Ricardo’s company survived the devastating hyperinflation of 1989, which went from 460% in April to 764% in May, it did not outlast the economic policy that was used to try to halt inflation. Starting in 1991, the National Congress passed the Convertibility Plan, which pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar and precipitated aid from the United States and the International Monetary Fund. It did stop inflation, and generated a market-friendly business environment, stimulating growth, selling off public utilities, public transport, communications, and mining rights that landed in private hands. It also meant the demise of Argentine manufacturing amid a flood of imports.

Ricardo Schwartzman’s company, according to his version, failed for those reasons. The family lost their two apartments and their weekend home, and stopped spending summers in Uruguay. The children had to seek scholarships to keep studying in the Jewish private schools Ort and Betel, and the family moved into a rented apartment. This is when Silvana became pregnant with Diego. “There was no chance to get him out,” was her way of referring to medically terminating the pregnancy.

We were talking in a café in one of the towers of Belgrano, an upper-middle-class residential area in the north of Buenos Aires. Silvana was wearing tennis-style athletic gear. In the chair next to her she rested the Wimbledon racket that she had brought back from her recent trip to England to attend the Grand Slam event. It was 7 p.m., and we wouldn’t part ways until 10 that night.

After Diego’s birth, Ricardo found a way out of bankruptcy. In a store window at a mall he saw plastic pacifiers that had become popular among adolescents and youths. He bought some, took them to a plastic injector he knew and they mocked up three forms. According to family lore, he sold 2 million of the pacifiers in just a few months, earning some $300,000. With those profits they got back on their feet and paid debts, but the teen pacifier craze was short-lived—and the next Argentine financial crisis, in 2001, did them in again.

From the end of 2001 into 2002, Argentina had five presidents in 10 days. The economy collapsed, and the magic formula of 1 peso to the dollar became unsustainable. Currency exchanges went haywire (today a dollar costs 300 pesos on the black market), wrecking many businesses like the one belonging to the young tennis player’s family. At ages 9 and 10, Diego won 24 tournaments. This new bankruptcy put his continuation in the sport in jeopardy.

“I told him I’d prostitute myself before making him leave tennis,” Silvana said.

Instead, Silvana found work as a decorator on the Avenida Santa Fe near Larrea Street, a shopping area in the tony Barrio Norte of the Argentine capital, while Ricardo saw another opportunity. At a Maccabee game he saw the silicone bracelets that had become popular with athletes, Tour de France cyclists, Hollywood celebrities, and others who wore them as part of a cancer awareness campaign. Ricardo again turned to the plastic injector, and ramped up a massive run of bracelets. Silvana took charge of distribution and sales at the tournaments she was attending. She would bring a bag with 4,000 bracelets. Diego and other players helped sell them and kept 20% of sales. The bracelets financed the family life and Diego’s tennis career—which still needed more support.

At the time, the Argentine Tennis Association (AAT, for its Spanish initials) selected a group of tennis players whose travel it would underwrite, but Diego was not among them. So Ricardo would frantically hunt for sponsors among friends, acquaintances, and institutions like the Club Nautico Hacoaj, where Diego practiced. Ricardo remembers trying to persuade people with Diego’s good results, and potential sponsors replied by expressing the limits they saw in his son’s small stature.

The situation changed when a friend from Hacoaj put Ricardo in touch with an investor, who became part of a consortium. Ricardo, who prefers not to name them, made them all sign a six-month contract, stating that they would pay for doctors, trainers, physical therapists, hotels, and travel. In return, they would keep 90% of Diego’s winnings. The contract was signed when Diego turned 16.

“We started with 90% for the sponsors, and 10% for Diego, and if he won X amount of dollars it moved to 70%-30%. Once Diego would pass the million-dollar-a-year mark, Diego would keep 90%,” Ricardo said. On Diego’s 30th birthday this month, the contract expired, although the patrons remain linked to his career in other ways. For Diego, they are like uncles.

As a teenager Diego started psychological treatment, to treat a number of fears that were holding him back. “He needed to break away from me because we were too close: He didn’t want to travel to tournaments if I didn’t go,” Silvana said, talking about how she chaperoned Diego to tournaments during the periods when money lacked, and how she tried to fulfill Diego’s main request, which was that there be a television in the hotel room.

Years later, US Open fans in 2017 witnessed some of this mother-son bond. It was Sept. 1, when Diego beat Marin Cilic, the fifth seed, 4-6, 7-5, 7-5, 6-4. In the fourth game of the first set, Schwartzman started to make signs toward the stands. When the chair umpire asked what was going on, the Argentine answered: “It’s my mother,” referring to her bombastic gestures at each point he lost. Silvana left his field of view.

When she watches Diego on television, she’s even more nervous. She lifts weights and does situps. She gets chills. “The day he beat Nadal I thought I was having a stroke,” she told me. She shows me her Instagram feed where you can see her way of celebrating his victories.

When Diego travels, Silvana stays at her son’s home in a gated neighborhood called Nordelta, in the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires, and watches the two dogs, Bob and Ziggy. Silvana says she lives the life of a millionaire in Nordelta, and of a plebe in Villa Crespo in downtown Buenos Aires. She still works as an interior designer. Her expertise is in by-the-hour hotels, where couples enjoy rooms with mirrors and other stimulating décor.

Ricardo tends to the family business selling hipstery apparel at Guinche 21, just off the Plaza Serano de Palermo, a central tourist spot in the Argentine capital. His partners are his son Matías and his son-in-law Marcelo Alvarez. They sell hats, T-shirts, bags, men’s bathing suits. Diego models the clothes.

Ricardo was in the news earlier this year for having been attacked. “He started telling me he was going to cut my face,” Ricardo recounts. The scene was caught on security camera video and was broadcast in the national media. The thief was caught, his switchblade impounded along with the stolen booty: cash, a cell phone, a speaker, and two backpacks with eight hats worth some 32,000 pesos, or less than $110.

At that same store is where we met. We crossed slowly to a café on the opposite side of the street. Ricardo moves with a walker. Three years ago, they operated on three herniated discs and a year later he felt nothing in his leg: The surgeons had blocked a nerve leading into the quadricep. Since then he has only been able to walk with help, and he has become more emotional. He cried twice in the two hours of our talk, recalling some of his son’s sporting triumphs, and the economic difficulties he had lived through. He spoke with enthusiasm about the good times he had as a businessman, and with pain when talking about his bankruptcies and debacles. He never fully recovered financially, and still rents the place where he lives with his wife.

“I never thought Diego would go so far in tennis,” he told me. “In my most optimistic days I thought he might be top 100.”

Like his wife, Ricardo gets worked up watching Diego play. When a match is going badly, he leaves to take a drive to get away from the TV. “I try not to write to him when he’s in competition. We’ve been more in touch lately. Before he was colder to me. He’s used to being alone on court. But since he’s found a girlfriend he’s become more affectionate. He calls me to see how I’m doing.”

Before we say goodbye he tells me details of the robbery and asks me a question: “Did you know that right around that same time they robbed Diego?”

Between Wimbledon, in June, and the beginning of the US Open this week, Peque did not have his best months. In preparation for Wimbledon, he traveled to England to the ATP in Eastbourne: He lost on June 22 in the first round. When he returned to his hotel room, he found his backpack—where he had money, a watch, credit cards, and even his passport—was gone. At Wimbledon, he lost in the second round to Liam Broady (ranked 152nd in the world) in a match he had in hand, up two sets to one and 3-0 in the fourth, when Broady counterattacked, winning the tie-breaker 8-6 and then cruising in the fifth, 6-1.

Twenty days later, Peque lost in the first round of the ATP 500 in Hamburg. “It’s frustrating … I can’t believe what’s happening. Enough, Juan. Enough, I can’t anymore,” he yelled in the general direction of his coach during his debut at the clay court tournament, where he was seeded third. A Finn, Emil Ruusuvuori (43rd), beat him 7-5, 6-4 in two hours and 22 minutes. When they were at 3-3 in the second set, Diego broke his racket on the clay. Four days earlier he had lost 6-1, 6-0 in the quarterfinals of the ATP Bastad, against the veteran Spaniard Pablo Carreno Busta.

In July, he returned to Buenos Aires to see his family and friends and to prepare for the North American leg of the circuit. That’s when we made arrangements to meet in New York, ahead of the US Open.

In August, the North American tour started in Toronto, and from there to Cincinnati. In Canada, Diego lost in the second round to Alberto Ramos Vinolas (ranked 43rd). In Cincinnati he won his first two matches and in the third lost to Stefanos Tsitsipas (No. 7), 6-3, 6-3. Diego posted to Instagram: “Twisted day today! Congrats to @stefanostsitsipas98 for the win … but a positive week personally returning to feeling competitive again.”

In New York he posted photos to Instagram of him and his girlfriend, Eugenia De Martino, who follows him for most of the tour. They settled into the Hamptons to rest up in preparation for the US Open.

Last Friday I watched Schwartzman training on Practice Court 8 at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. Chela helped him under the oppressive midday heat. He was hitting against the Serbian Dusan Lajovic.

Schwartzman was wearing a yellow hat and a green-toned outfit. He tells our photographer where to stand during practice. He seems serious. He strikes a backhand, jumping in a perfect, singly graceful and forceful movement. He conserves his energy. The Serbian offers him a dropshot that he doesn’t chase, but he tells Chela: “I’d get that one.”

Nearby is Juan ‘Pico’ Monaco, former world No. 10 and Schwartzman’s manager along with other players and former players. Pico helped Diego when he was young, sparring with him, inviting him to warm-up tournaments in Tandil, Buenos Aires, and Uruguay, and seeing his potential. Now he serves as an agent helping him with his image and his relationship with sponsors. “Brands like him for his charisma and because he’s beloved on the circuit,” Pico tells me while keeping one eye on the practice session.

“Good one, Nene,” a friend says when Diego rips a passing shot down the line.

Monaco, who just got back from Israel two weeks ago, wanted Peque to play the ATP Tel Aviv at the end of September. The idea would be to combine that tournament with some clinics and talks. “He’s never been to Israel, and this is a great chance to go: Because of his family’s story it would be a historic trip.”

Back in the New York hotel bar I asked Diego about his relationship to Judaism. He spoke about the Hacoaj, the festivals and rituals, family reunions, Middle Eastern food. His closest friends now are from BarKojba, the Jewish club that Diego’s brother Matías joined. Unlike his brothers and sisters, who all went to Jewish schools and were bar and bat mitzvahed, Diego missed out because that period of his life coincided with the family’s time of hardship. He seems very excited by his upcoming first trip to Israel.

After tennis, he says he would like to work organizing sporting events, in marketing. And also to work outside of tennis, investing and financing other people’s projects. “Also to get to know worlds I don’t know, to travel for fun instead of traveling to play tennis, which is completely different. What I find most difficult about tennis is the travel,” he says, leaving his lemonade half finished.

At the end of our conversation there were still 72 hours before his first match at the US Open, but Diego was already back into the details and work of the life of an elite tennis player. He held forth on the differing velocities of the different courts at the Tennis Center and how much he prefers playing at night in New York’s September humidity. His debut was scheduled for Tuesday at 8:15 p.m. against the American Jack Sock. Clumsily, I asked him if he still gets nervous in matches. “Of course,” he says. “You don’t get nervous before an important interview? I get nerves. The key is knowing how to control them.”

On Tuesday, Diego entered Louis Armstrong Stadium after 9 p.m., shuffling his feet with short and quick movements. Without his hat on you could see his serious and concentrated face and recognize some of those nerves he had talked about. The conditions were right for him in New York City: a humid night on a slower-playing court. During the warm-ups, the fans made clear they’d been visiting the drinks stand.

Sock was also born in 1992 and had also been in the world top 10 in 2017, but had fallen to 107th. The match had barely begun before Sock was overwhelming Diego with whipped forehands and a serve breaking 130 mph. Diego, known for having one of the best return games on the circuit, was erratic with that celebrated part of his game, and with the rest of his game as well. He failed to impose long points as planned, and nothing of what he’d practiced the week before seemed to be working for him. He was exasperated by his unforced errors, sharing his frustration with his box: His coach Chela, his manager Monaco, and his girlfriend. He vented by smacking his shoes as if knocking them clean of clay. After losing the first set 6-3, the second was more even, but in a key moment he dumped an easy volley, sending him into a funk: He lost the second set 7-5.

Now and again you could hear “Vamos, Diego!” with an Argentine accent, and once, but only once, a group of Argentines in the second deck launched into a chant that used to be a tribute to Maradona: “Olé, olé, olé, olé Diego, Diego.”

Around 11 p.m., Ben Stiller became part of the show. The stadium camera, panning across the faces of men and women drinking beer, some of whom chugged their drinks in response, found the actor in the first row, who returned a shy smile unlike what you’d expect from a star. The night before, Stiller had been invited by Diego to hit some balls there in the stadium—video of the event had gone viral in tennis circles. The actor is a big fan of the Argentine, whom he met at the 2019 US Open following Diego’s straight-sets loss to Nadal in the quarterfinals. Since then they’ve texted and gone to dinner together. On Tuesday night, the actor thought he was watching his friend go down.

But Diego was smiled upon with good fortune. At the start of the third set, Sock asked for a medical trainer to massage out soreness in his back. When he returned to the court, the pain only seemed to increase. And so began a completely different match, with Diego winning the third 6-0 without really celebrating any winning points or getting angry with himself for the few errors he committed. Sock threw in the towel at the start of the fourth set.

“I was lucky, Jack was on his way to beating me in three sets, because he was playing much better than me,” Schwartzman said with candor in the post-match on-court interview. He stayed a while posing for fan selfies, talking with Argentines easily identified by their national and Boca Juniors soccer jerseys. In parallel, Stiller waited patiently for a security cordon of four police escorts to form around him, and he left smiling after one selfie with a fan but without stopping for autographs, nor for me as I stood waiting on his path to ask him why he was such a fan of Diego’s.

I did have part of the answer already. During last year’s US Open he had tweeted several times during one of Schwartzman’s matches: “Love his heart.”

Translated from Spanish by Matthew Fishbane.

Martín Sivak is the author of eight works of nonfiction, including the international bestseller El salto de papá (2017). A journalist since the age of 18, he holds a Ph.D. in Latin American history from New York University and is a regular contributor to El País, a daily newspaper in Spain.