It’s Shabbat in Sugar Land, and dozens of rabid Texans are clanging cowbells to the tune of “Bad Boys,” the theme song from Cops, as three referees skate gracefully around the ice. Tonight, the first 45 fans at the entrance to the Sugar Land Ice and Sports Center were rewarded with free cowbells—black ones with the Imperials’ logo. Along one side of the arena are five rows of blue bleachers occupied by fans bundled up under coats and blankets. On the opposite end, behind the team’s benches, stand the coaches, in business suits. Giant flags of the United States and Texas hang beside a scoreboard behind one of the nets.

Filing onto the ice now on this cool November night are the hometown Imperials, wearing camouflage jerseys in support of the U.S. military.

“Who’s ready for Friday night NA3HL hockey?” the public-address announcer bellows.

The Sugar Land Imperials, a junior-league hockey team with a record of four wins and nine losses, are currently in last place in the North American Tier 3 Hockey League’s South Division. Their opponents, a physical and cocky bunch from Topeka, Kansas, are battling for the South’s top spot and have won eight of nine road games on the season. Their players possess first names such as Bailey, Bear, Colton, and Trey.

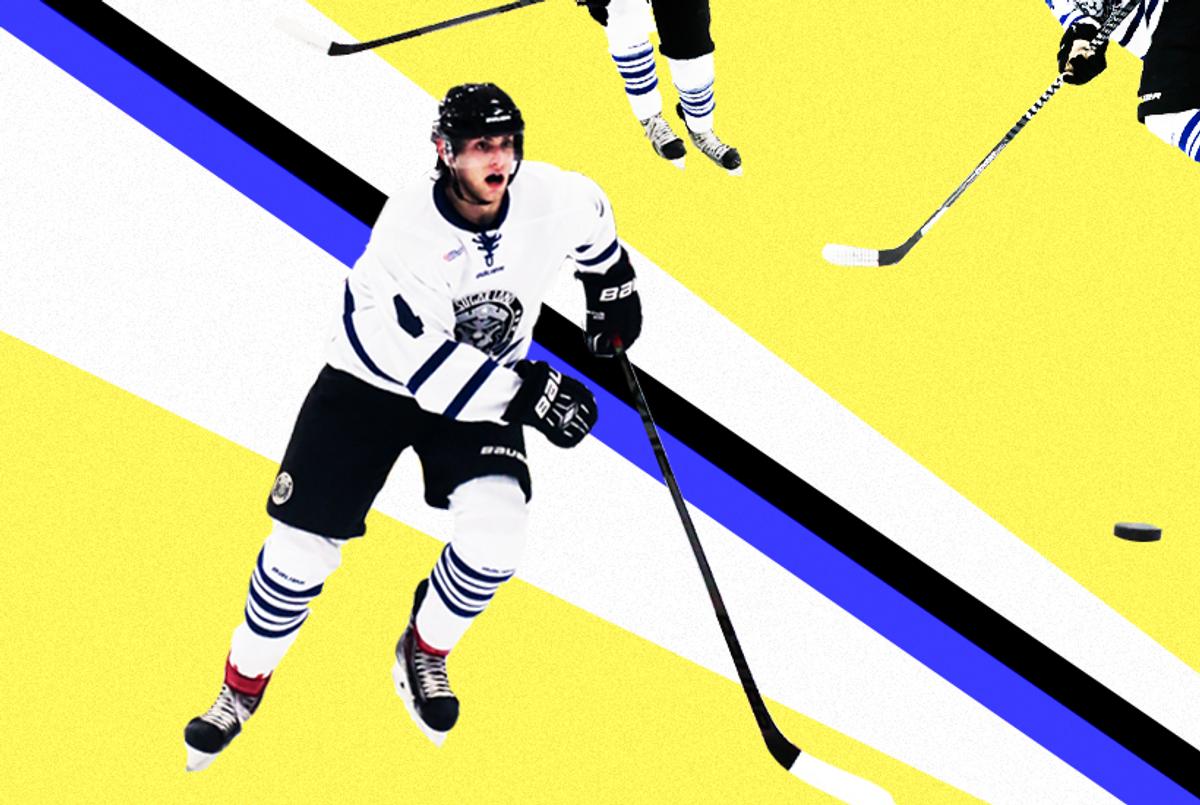

The puck drops; the game is swift and violent. Wearing No. 4 for Sugar Land is an 18-year-old forward from New Jersey named Joshua Rocco. About six months earlier, Rocco was on a stage on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, singing in Hebrew with his high-school a cappella group, the Heschel Harmonizers. A Jewish kid who attended Solomon Schecter Day School of Bergen County—not exactly a pipeline for elite hockey prospects—Rocco’s pursuit of his dream has brought him here, to this unlikely place about 20 miles southwest of Houston. According to Elliot Weiselberg, host of The Court Report, a weekly radio show on the Nachum Segal Network about the Metropolitan Yeshiva High School Athletic League, Rocco’s case is “extremely rare,” if not unheard of. To Weiselberg’s knowledge, Rocco is the only athlete from a Yeshiva League school to ever play junior hockey.

For the first time, Rocco isn’t part of a Jewish community. He told me he misses it, but that’s OK—his hockey teammates are like family. And when he laces up his skates, all else is forgotten. “When I’m in the locker room three minutes before a game, nothing else in the world matters,” Rocco told me. “And when I’m out on the ice, I have no other worries.”

And on this Friday night, the Imperials are trailing 5 to 1 in the second period against the Topeka Capitals when Rocco notices, while skating out of the zone, the largest player on his team—whose nickname is Big Baby—sprawled out on the ice. A Topeka player named Yusa is hovering over Big Baby, with his stick high. Rocco hadn’t seen what had happened, but he’s aware of this much: Big Baby has been taken down. The play was dirty. And the culprit, who has turned his back to Rocco, stands within reach.

“I gotta do something,” Rocco knows.

***

A few weeks before his departure for Texas, I sat beside Rocco inside his Cresskill, New Jersey, home, eating his mother’s matzo ball soup. Rocco, who’s listed at 6 foot 2 and 195 pounds, had on his favorite New York Rangers cap turned backward. My bowl contained three matzo balls; Rocco’s about 10.

“I always was a big kid, but I wasn’t violent in the slightest,” he’d told me that day. His mouth was swollen—not from any on-ice incident, but from having had his wisdom teeth pulled. The soup was delicious.

“This will be making its way to Texas, you should know,” his mother, Dana, said. “Vats of frozen soup.”

Picturing this kid dishing out brutality wasn’t easy. He had the size, but not the bravado I associated with hockey players. Rather, he was introspective and intellectually curious, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. He said he’d been making a conscious effort to raise his intensity level on the ice—that in the past, sometimes he could get passive out there.

Rocco’s upstairs bedroom is a shrine to hockey. On the wall behind his bed are three nearly life-sized images of NHL players in action. Elsewhere hang jerseys—like those of Jaromir Jagr and Team USA—and an array of sticks and pictures of youth teams Rocco once played on. The nightstand and desk next to his bed are topped with trophies, and on the other side, helmets rest atop a bookcase. Its shelves are lined with trinkets: a statuette of a music symbol—the treble clef; a small booklet showing a Star of David; a Hallmark-type card of a Golden Retriever puppy; and a baby picture of himself that says, “Joshua.”

Rocco first put on skates at age 4 (whether his Canadian blood was a factor in his instant connection to the ice—his mother is from Vancouver—he’s not certain). At age 9 he played for a hockey team called the Kodiak Bears; a few years later he joined the North Jersey Avalanche. Tall and athletic, he excelled. His goal was to play Division I college hockey.

When he was 15, he attended a camp at Miami University in Ohio. It was a wake-up call. Players half his size had faster shots than him. His skating and stick-handling ability were inferior to the other campers’. The coaches explained to Rocco that it was due to poor technique and fundamentals.

Rocco had spent a majority of his youth playing B Level hockey (the levels of youth hockey are AAA—the most competitive—then AA, A, and B), where the emphasis on fun and participation rather than winning, Rocco believes, stunted his growth. “I was very behind,” Rocco said.

Rocco’s high school, Abraham Joshua Heschel School, doesn’t field an ice hockey team. And so Rocco played club hockey with the New Jersey Ice Dogs, an A Level club, and began facing stiffer competition. He started waking up at 4:45 a.m. twice a week to practice at a local rink. On weekends he trained with Randy Velischek, a former NHL defenseman, who simulated real-game conditions and ran Rocco through NHL drills. As his skills improved, so did his confidence.

One day he was contacted by Jarod Palmer, a former player for the NHL’s Minnesota Wild who’d instructed Rocco at a camp. Palmer told Rocco he’d just become head coach of a junior league expansion franchise, the Sugar Land Imperials, and was looking for players. He invited Rocco to Texas to try out.

Rocco traveled to Sugar Land last May for the tryout. Later that month, Rocco had a concert with the Heschel Harmonizers. Wearing a dress shirt and tie and towering over most of his fellow singers, Rocco—who has a four-octave vocal range—belted out tunes such as “Ivdu Et HaShem B’Simcha” and “The Road Home.”

A few weeks later, on the day of his high-school graduation, he received a text from Palmer, Sugar Land’s coach: The Imperials had selected him in the seventh round of the NA3HL Draft. He was off to Texas.

***

Sugar Land is a city of about 85,000 residents dominated by strip malls, master-planned communities, and miles and miles of empty space—all of it linked by ramps, bridges, and freeways. Big trucks barrel down its roads past churches the size of shopping malls. Located in Fort Bend County, the area’s congressman used to be former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay.

Rich in sugar cane, the town was named Sugar Land in 1853 by a plantation owner named Benjamin Franklin Terry, who would go on to become commander of Terry’s Texas Rangers, the Confederate cavalry regiment. (He perished in battle in Kentucky in 1861.) Slaves made up a majority of Fort Bend County’s population before the Civil War, making the sugar industry there profitable. But with the Confederacy’s collapse and slavery outlawed, property owners leased convicts for cheap from the nearby state penitentiary. Prisoners nicknamed Sugar Land the “Hellhole on the Brazos,” in reference to the brutal working conditions in the sugar fields and the river that flows nearby.

For much of the 20th century, Sugar Land was a company town, home to Imperial Sugar. The city was incorporated in 1959 but remained a small agrarian community—the population was only about 9,000 in 1980—until the latter part of the century, when Houston greatly expanded. Today, the main building of the former Central Unit Prison, a red-brick structure with a huge, austere front lawn, is a science museum, and Sugar Land is one of the fastest developing and most prosperous cities in Texas—a place in which sports celebrities like Charles Barkley, Hakeem Olajuwan, and Shaquille O’Neal have been reported to own homes. In 2012, baseball great Roger Clemens, his reputation badly damaged after steroid allegations, tried a comeback at age 50 with the Sugar Land Skeeters, the city’s new minor-league baseball team.

The Imperials were founded in 2013. The NA3HL—with 31 teams spread across five divisions—is one of several Tier III junior hockey leagues in the country. (The highest level of juniors in the United States is a Tier I league, the USHL, followed by the NAHL, which is Tier II. Junior hockey players are considered amateurs, although they can be drafted and traded. In Canada, the top level, “major junior,” is deemed professional by the NCAA.)

Rocco arrived in Sugar Land in August, a time of sweltering heat. As part of his initiation for the team, he had to dress up as a woman and take a veteran teammate—a player from North Pole, Alaska—on a “date” to the local Hooters on Southwest Freeway.

Life moved at a slower pace than in the Northeast. People said “y’all.” Gas stations, churches, and trucks were everywhere. (“The bigger the truck, the bigger the guy,” Rocco observed.) A water tower reading “Sugar Land” could sometimes be seen on the horizon. It reminded Rocco of Friday Night Lights.

In junior hockey tradition, players live with host families, who are paid a monthly stipend in exchange for lodging and meals. The billet families, as they’re known, make up much of the loyal fan base of junior hockey teams. Billet moms and dads often deck out in team jerseys and cheer for their billet sons as if they were their own flesh and blood.

Back in New Jersey, Rocco and his parents had decided it was best that he be billeted with a Jewish family. But there aren’t many Jews in Sugar Land; in the Yellow Pages, I counted about 50 churches and 0 synagogues in Sugar Land proper.

The Goulds are a family who live in Sienna Plantation, a tranquil, 7,000-acre master-planned community lying just east of the Brazos River in nearby Missouri City. The father, Eric Gould, the grandson of Holocaust survivors, hails from hockey-crazed Buffalo and used to work for the NHL in Dallas as an off-ice official. The mother, Carrie Gould, works at the Sugar Land Ice and Sports Center as the Imperials’ community relations manager. On game days she’s a mainstay on the sidelines with her Imperials jersey and peppy spirit. She’s also the team’s billet coordinator, in charge of matching players with host families. For Rocco, the Goulds were a natural fit.

The Goulds settled in the Sugar Land area about seven years ago. In Southern fashion, their new neighbors were welcoming. “When we moved here, it was, ‘Hi, nice to meet you. What church do you go to?’ ” Eric Gould recalled. He describes the area’s Jewish community as “small but dedicated,” much like the hockey community.

The Goulds have two sons: Eli, 14, and Jeb, 9, both of whom play for Sugar Land’s Junior Imperials teams, the franchise’s youth divisions. Hockey is a way of life inside the Gould household. The NHL Network airs from multiple TV’s, pucks fly, and the Imperials logo, a sinister-looking creature that looks half lion, half rabid dog, peers menacingly out from caps, sweatshirts, and other gear.

Also staying at the house early in the season was a teammate of Rocco’s, a baby-faced, 145-pound Floridian named John Cuni. Rocco and Cuni acted like big brothers to the Gould boys, horsing around with them and helping out at youth practices.

Another thing Rocco does at the Goulds’ house is eat. He hopes to get up to 225 pounds, which, judging by his elephantine diet and all the weights he lifts, is a target he should meet with ease. Rocco eats a devastating amount of food. His mornings begin at 8 o’clock, at which time he heads downstairs to the Goulds’ kitchen and consumes six Eggo waffles. “Or I have, like, two bowls of Lucky Charms,” he explained to me. “And I might have an apple.”

He added, “I definitely have some orange juice and maybe some chocolate milk, because I hate the taste of regular milk.” He packs a lunch that consists of three Gatorades, “two to three thick turkey sandwiches,” and a Clif Bar. “I just eat all the time,” he concluded. In a typical day, he estimated, he takes in the calories of about four healthy adults.

When he gets home from the rink, Rocco eats a lot more and watches TV. He also talks on the phone with friends from Heschel, among them the former head of the Harmonizers, who goes to Princeton, and another friend, who attends Brown.

***

The Imperials season started in September. In just his second career game, Rocco tallied an assist. The Imperials got off to a rough start, however, losing nine of their first 12 games. During a game against the Dallas Jr. Stars in October, the Imperials were involved in a huge melee in which nine players were tossed—including Cuni, who was labeled an “instigator” and suspended.

I flew down to Sugar Land in the middle of November for the Topeka series. Rocco hadn’t scored a point since his assist a month earlier, but when we met, he told me he’d been improving in every facet of the game, as this was the first time he’d devoted his life almost exclusively to hockey.

Over the summer, Rocco had told me that “lots of fights break out” between Topeka and Sugar Land. In fact, Topeka led the entire NA3HL in fights last season, with 31, according to Dropyourgloves.com, which tracks hockey brawls. Would something go down? As the action got under way, I thought of a fight I’d read about in a USHL game, in which a player for the Dubuque Fighting Saints cracked his head on the ice and had a seizure.

The Imperials’ arena filled with loud stadium music, the sound of a frozen puck smacking from stick to stick, and the nonstop thud of bodies flying into the boards. Standing behind one of the nets, their foreheads pressed up against the glass, were three guys, probably in their thirties, downing beers and heckling the opposition. The most outspoken of them, who sported a dark, razor-thin mustache, was focused on a particular Topeka player whose name amused him. “Ro-ers!” he called out, in a growling, sing-songy tone, “More like Blow-ers. Ha ha!” His sidekicks cackled their support. Topeka scored four times in the first period.

During the first intermission, the three hecklers stumbled onto the ice. An arena official hauled out a cart holding water jugs and bins of hot dogs. “On your mark, get set, eat those hot dogs!” yelled the P.A. announcer. “Eat It,” by Weird Al Yankovic blasted from the loudspeakers. After a rather unpleasant scene, the thin-mustached guy was declared the winner.

Things only worsened in the second period for Sugar Land. Roers—AKA “Blowers,” first name Hank—scored twice to make it 6-1 Capitals. The crowd had gone quiet. The only cowbells still audible were being rattled by the girlfriends of two Topeka players, who’d made the trip all the way from Kansas.

Topeka started committing penalties: first for hooking, then for roughing, then for unsportsmanlike conduct. After a Capitals player delivered a crushing but legal check against the boards, the entire Topeka bench yelped and hollered and banged their sticks in celebration.

It wasn’t long after that when Rocco saw Big Baby flat on the ice, while a Topeka forward, Yusa, stood over him with his stick high.

Rocco nudged Yusa in the back, to get his attention. Yusa turned around.

“You wanna go?” Rocco said.

“Yeah,” Yusa responded.

Both players tossed down their sticks, shook off their gloves, and raised their fists into the fighting stance. The cowbells returned to life. The three hecklers pounded on the glass in bloodthirsty delight. But the ritualistic nature of the combat allowed plenty of time for one of the refs to hustle on over and scoot between Rocco and Yusa. Once the players separated, Rocco’s helmet was off, his hair was all messed up, and his mouthpiece was popping out. He headed over to his bench. There, an official informed him he’s been ejected for fighting. Rocco skated off the ice by himself with a blank expression, into the locker room. In the bleachers, an incensed male fan holding a plastic beer cup objected. “You can’t call a penalty for fighting if you don’t let ’em fight!” he shouted.

When Rocco’s teammates re-joined him in the locker room at the second intermission, Big Baby went up to Rocco. “I’ve got your back, you’ve got mine,” Big Baby said.

***

The next day, Rocco and I had lunch in the Sugar Land Town Square, a maze of strip malls that is less charming than it sounds. We ate at the Flying Saucer Draught Emporium. When Hall & Oates’ 1982 song “Maneater” came on, Rocco sang along in a high-octave voice as he surveyed the menu. A chipper young waitress with the sharpest Texas drawl I’d heard all weekend took our order.

“I’m going to get the buffalo wings,” Rocco said. When the food arrived, he dismantled those, along with an order of French fries, washing it all down with his favorite drink, Arnold Palmer, of which he had five refills. His teammates had been shocked by his display of fire the previous night. “I’d never seen that out of him,” Cuni would tell me later that day. “I didn’t see him dropping the gloves in the middle of the game. We didn’t expect it. We were like, ‘Wow.’ But we’re happy and proud of him.”

Rocco’s billet father, too, Mr. Gould, would express surprise, calling the episode “a newer expression of fire for Josh—the first time he’s really gotten after somebody like that.” While more restrained in his endorsement than Cuni, Mr. Gould did note that “standing up for his teammate was a good thing.” (Later in the season, Cuni was traded to Topeka.)

After lunch, I drove Rocco back to Missouri City. Heading southeast on Texas State Highway 6, we crossed Oilfield Road and passed several local landmarks: the International House of Stogies, the Colony Creek Community Church, the Fort Bend Community Church, the Hoggs N Chicks restaurant. Eventually we turned right on Sienna Parkway, a long straightaway.

“What’s the speed limit here?” Rocco asked, glancing at the speedometer. I could sense that he was commenting on my driving. I was going about 45 MPH in a 35-MPH zone. “Wow, it feels like we’re going 25,” he said. “Cuni drives like 50 or 60. Everyone I’ve been with speeds. Crazy.” Cuni plays country music in the car, Rocco said. He conceded that he’d warmed up a bit to the genre; in fact, he’d even downloaded a few country songs. I asked Rocco about the other biggest differences between Texas and back home.

“I see a lot of those—what is it called?” he said, “With the fish and the cross?”

“The Jesus Fish?” I said.

“Yes.” Rocco Googled “Jesus Fish” on his phone and read aloud about its significance.

Finally, I asked him about his ejection the night before.

It all happened so fast, Rocco said—and he was so full of adrenaline—that he didn’t have time to think.

“What were you thinking about when you skated off the ice?” I asked.

There was a brief pause, and then Rocco flashed a grin.

“I wish they would’ve let us fight,” he said.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Louie Lazar is a journalist living in New York. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Grantland, and the Jerusalem Post.

Louie Lazar is a journalist living in New York. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Grantland, and the Jerusalem Post.