An exhibition at the Italian American Museum in New York recently celebrated Gino Bartali, whose fame as a cycling champion has been amplified in recent years by his alleged participation in the rescue of Jews during World War II. Films and a theater play accompanied Yad Vashem’s recognition of Bartali as a righteous gentile in 2013.

Bartali never claimed to have been a rescuer, nor did any of the organizers of the Italian rescue networks mention him. Historians have kept silent on the matter: None of the scholars in the field have so far endorsed it.

In the absence of reliable research, curators and institutions who present portrayals of Bartali as a rescuer of Jews to their audience, have little to rely on except for the enthusiasm of the press and the endorsement of colleagues.

Regardless of what research may uncover in the future, how does Bartali’s story fit in with what we know of the rescue of Jews? A recent article by Michele Sarfatti, one of the most respected authorities on the history of the Shoah in Italy, offers an overview of existing historical evidence and testimonies. His dispassionate analysis may provide tools to ask relevant questions and ponder on humanity and myths.

After Sept. 8, 1943, all Jews in Italy under the Italian Social Republic and German occupation were at risk of arrest and deportation. Their survival depended on, among many factors, their ability to go into hiding with fake names and falsified identity cards.

Because of frequent police checks, all Italians needed identity cards to move within cities as well as to reside in pensions and boarding houses. They also needed identity documents to obtain ration cards to purchase food.

Italian Jews needed false identity cards for these same reasons. This was especially the case in Florence, the only city in Italy where Jews who went to register for ration cards exhibiting their “true” identities were arrested.

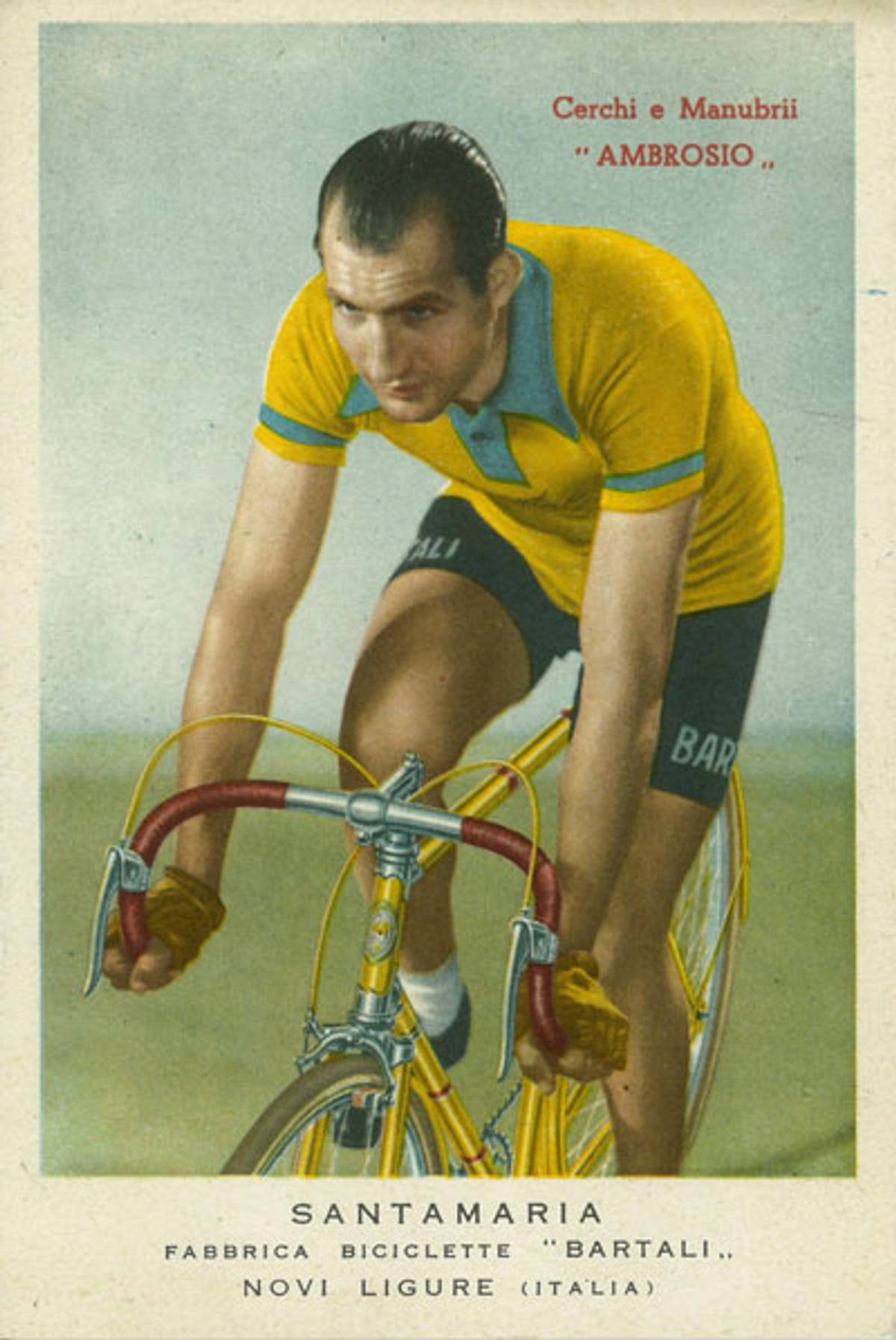

Gino Bartali bicycle promotional postcard, 1950-55. (Image courtesy Michael Haddad, Guest Curator, Italian American Museum)

Foreign Jewish refugees—particularly numerous in Florence—needed false identity cards primarily to reside in pensions or boarding houses, because, given their limited knowledge of Italian, they generally avoided roaming the streets.

Typically, false identity cards bore addresses from areas of southern Italy that had already been freed by the Allies, thus rendering verification impossible. However, this was also a source of danger, since the carriers of false documents might have cards from Puglia or Sicily but speak with strong Venetian or Florentine accents. Or, in the course of police checks, they might meet people who purposely engaged in conversations that required knowledge of details about those municipalities.

The fabrication of false identity cards occurred in several phases that could be carried out at the same time or in separate places. First, original blank forms were either stolen by anti-fascist city clerks or printed clandestinely. Next, personal data had to be filled in on each card. Finally, photographs and falsified municipal stamps, with the city name and seal, had to be affixed on cards. After this final stage, the cards needed to be distributed.

It should be noted that in Italy under the Italian Social Republic and German occupation, the first individuals to seek false identity cards were anti-Fascists who had been particularly exposed during the “45 days” between the deposition of Mussolini and the armistice.

In 1978, Alexander Ramati, a Polish-American journalist who had been a reporter during World War II, published a volume in English on the Nazi occupation of Assisi and the hiding of Jews, which was translated into Italian in 1981. The book’s U.S. edition was titled The Assisi Underground: The Priests Who Rescued Jews: as Told By Padre Rufino Niccacci. Ramati’s examination of the Nazi occupation of Assisi story was based on the account of Father Rufino Niccacci. According to the Ramati-Niccacci account, the latter, on Nov. 23, 1943, went to Archbishop of Florence Elia Dalla Costa to talk about Jews hidden in Assisi. Dalla Costa told Niccacci that he had seen the false identity cards that had been fabricated in Assisi, and asked him to produce some for the Jews hidden in Florence as well.

The book continues stating that Dalla Costa enlisted as courier the cyclist Gino Bartali (the name used by Ramati in both the U.S. and British editions is “Gino Battaglia.” In the Italian translation, it was replaced with “Gino Bartali”), who reached Assisi on a bicycle “bringing photographs and then returning with identity cards a day or two later.” The material was concealed in the bicycle. Ramati declared, “As usual, he [Bartali/Battaglia] pulled the grips off his handlebars and unscrewed his seat to take out the photographs and papers hidden inside the bicycle frame.”

Ramati-Niccacci also writes that the bishop of Assisi “had a meeting in Perugia with Cardinal della Costa’s [sic] emissary Giorgio La Pira.” A few pages later he states that documents were fabricated “for those whose photographs were carried to Assisi by Gino Battaglia or Giorgio La Pira.”

The narrative of Ramati-Niccacci contains many errors and inventions. For example, the book argues that on the day of Niccacci’s arrival in Florence, Nov. 23, 1943, the press reported the Italian government’s order to arrest all Jews present on Italian territory. Further, according to the book, on the same day, the Nazis raided Florentine convents searching for Jews in hiding there.

Ramati has Father Nicacci state: “I saw a whole family lined up against a wall and machine-gunned because a revolver had been found on one of them.”

In reality, the order of the Italian Social Republic was announced by the radio Nov. 30 and published by the press Dec. 1. The Nazi raid was carried out Nov. 26-27, and no one was shot.

Similarly, the courier activity between Florence and Assisi attributed by Ramati-Niccacci to the Florentine Catholic anti-Fascist Giorgio La Pira is not consistent with historical evidence. In fact, La Pira lived in the Dominican monastery of San Marco in Florence.

On Sept. 29, 1943, that religious house was searched and La Pira, sensing danger, moved to the home of friends at Fonterutoli, near Castellina in the Chianti region. On November 17, the monastery received an arrest warrant for La Pira. The Dominican Father Cipriano Ricotti brought La Pira the news, and consequently, La Pira went into hiding in the nearby village of Tregole. On Dec. 8, he moved to Rome, where he remained until the liberation of the city.

It is clear that the undoubtedly brave anti-Fascist Giorgio La Pira was not in the position to be a courier, nor did he ever claim to have been one.

Likewise, the courier activity between Florence and Assisi attributed by Ramati-Niccacci to Gino Bartali is not mentioned either in the testimonies of Florentine rescue organizers nor in Bartali’s private writings or public statements. All publications that describe it are based more or less explicitly on Ramati’s book.

In addition, Bartali’s role as a courier is explicitly contradicted by Don Aldo Brunacci, a presbyter of the Assisi Cathedral, who had been charged by his bishop to organize assistance for the Jews who had taken refuge there. Don Brunacci was, therefore, the main organizer of assistance in Assisi. As such he coordinated the fabrication of false identity cards and was informed of the existence of “ties” with the clergy of Florence and Genoa.

One of Brunacci’s valued associates was, in fact, Father Rufino Niccacci, who joined the group at a later time, giving, according to Brunacci, “a remarkable help because of his courageous entrepreneurship.” Brunacci added that “through his many contacts and courageous entrepreneurship he brought a great contribution to the whole organization” (Brunacci 1985, 12, 24). Brunacci further commented the entire book by Ramati: “This is nothing but a novel. The author certainly had in mind a script for a movie and could not find a person more suitable for this intent and above all with a more fervent imagination than Father Rufino.” After writing that he himself had gone several times to Perugia by bicycle for some “delicate mission,” Brunacci added, “Maybe this detail that Ramati learned through my articles gave him the idea of introducing Bartali among the characters of his novel!”

In short, Ramati-Niccacci invented Bartali’s role as a courier. But then, who produced and carried identity cards for Florentine Jews? Here the testimonies by the protagonists abound, even if they may not be enough to reconstruct the full picture of the facts. It is best then to present them separately.

The main actors were members of the Florentine Catholic Church; Tuscan Jews and those from Emilia-Romagna, some of whom were members of the Action Party; Catholic young women partisans also affiliated with the Florentine Action Party; perhaps a Bolognese Communist; and probably others. Many others collaborated with these principal actors, including an official at the Florence police station.

In October 1943, Don Leto Casini, a parish priest in Florence, was asked by Dalla Costa to work for a relief committee for foreign Jews, who needed “identity cards — of course, false.” In charge of the printing “was a clandestine typography in Bologna. I collected passport-size photographs and I handed them over to a young Jew from Bologna who was traveling almost every day between my location and the printing company. … The truly exceptional courier I am referring to was Mario Finzi.” Mario Finzi was arrested in Bologna in April 1944, deported to Auschwitz and killed.

Don Leto Casini was arrested in Florence on Nov. 26, 1943. In his pocket at the time, he had “25 photos delivered two minutes before, that I was supposed to send to Bologna on that same evening, to be attached to the same number of identity cards.” He was subsequently released.

A Jew from Pisa, Giorgio Nissim, was the organizer of the relief for the Jews in the area of Lucca. Initially, he obtained false identity cards in Genoa, where he went by train. In his memoirs, he wrote that once Father Ricotti had given him 30 photographs of Jewish women in hiding “to fabricate false cards” and that he returned from Genoa to Florence with counterfeit documents a few hours after the roundup of Nov. 26-27, 1943 in which most of those women had been arrested.

Later, Nissim arranged to manufacture the cards in Lucca. Because it was difficult for him to obtain blank ration cards, he organized exchanges of blank documents in unusual ways. For example, he later recorded that on one occasion, “In Florence I was in contact with Maria Enriquez Agnoletti [Anna Maria Enriques Agnoletti], whom I met in a church where the friendly exchange took place: blank identity cards on which photos were affixed with stamps that I carried in my pockets, for ration cards,” Nissim continued. “I remember the last time I saw her, she gave me a big pack of ration cards, while both of us were kneeling at an altar in the church of Santa Maria del Fiore.”

Anna Maria Enriques Agnoletti, daughter of a “mixed” marriage and nominally exempted from anti-Jewish persecution, had joined the Christian Social Movement (MCS). She worked with the Action Party in Florence, during the war. She was arrested for anti-Fascist activities in May 1944 and killed.

Anna Maria Enriques Agnoletti’s role in Nissim’s and other ID distribution networks is corroborated by many testimonies. On Nov. 20, 1943, Don Giuseppe Spaggiari, chaplain of the Cathedral of Livorno, one of Giorgio Nissim’s contacts, recorded a meeting with her. The anti-Fascist Emilio Angeli, father of Father Roberto Angeli, a parish priest in Livorno, and rescuer of Jews—later arrested and deported to Mauthausen, where he survived—recalled that Anna Maria Enriques Agnoletti and two municipal clerks from that city who were members of the MCS distributed identity and ration cards to local Jews. Speaking of her, Action Party member Maria Luigia Guaita wrote, “she helped and saved a great many Jews.”

Guaita herself fabricated false identity cards in Florence. It is not known whether those cards were for Jews or partisans, or both. She later wrote, “I remember that once I made a large number of identity cards with the stamp of the Municipality of Caltanissetta spelled with only one ‘S,’ and it was hard to track them down and replace them with correct ones.” Guaita also provided ration cards.

With regard to the actions of the Resistance, we should also recall that on Oct. 24, 1943, Leonardo Tarozzi, Communist of Bologna, brought to Florence a group of blank identity cards. But it is not known whether they were used for clandestine Jews.

Finally, two historians, Pandolfi and Cavarocchi, wrote: “Father Ricotti and Giancarlo Zoli [young Florentine Catholic anti-fascist] managed to obtain valuable documents with the help of members of the Resistance” and “Father Ricotti remembers that a woman partisan who had studied with him handed him a dry stamp of a city occupied by the Allies. It was then possible to start producing identity cards with the collaboration of the police officer [Vincenzo] Attanasio, whom the priest defined as very faithful to the organization.”

On Feb. 9, 1980, Matilde Cassin, a young Florentine Jew heavily involved with rescue efforts, told me that Don Casini and Father Ricotti were autonomous and somewhat in competition with one another. This could explain the duplication of the fabrication of identity cards in November 1943. The whole story indeed requires careful research. However, she stated that most of the Identity Documents she distributed were the work of Giorgio Nissim and of the San Marco monastery, while Casini provided others.

Matilde Cassin also told me that in May 1944, she brought to Milan some identity cards, maybe three, made by Father Ricotti. In fact, she went to Milan from the 26th to the 29th of April and returned on May 16 to then reach Switzerland as a clandestine.

Now that it is unfortunately too late to find any first-hand confirmation, I wonder if one of those three cards was for Giacomino Sarfatti. My father Giacomino had gone to England after the promulgation of anti-Jewish laws in Italy. There, after June 1940, he enlisted in the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), who sent him to Italy (before July 25, 1943) as a radio operator.

At the beginning of April 1944, Giacomino Sarfatti met in Milan with the partisan and Action Party member Maria Assunta Lorenzoni, called Tina, who had just escorted a group of clandestine Jews from Florence to Switzerland. The group consisted of Gualtiero Sarfatti, Eloisa Levi, and their son Gianfranco (Giacomino’s brother). Gianfranco then returned to Valle d’Aosta to participate in the Resistance and was killed in combat.

Back in London, Giacomino Sarfatti reported about his meeting in Milan with partisan and Action Party leaders, and added, “later she managed to get him an identity card and some ration cards.” It seems to me, although it is no longer verifiable, that the person who “managed to get him cards” referred to Matilde Cassin.

Tina Lorenzoni was killed during the battle for the liberation of Florence in August 1944. Historian and Action Party member Carlo Francovich wrote that Lorenzoni “provided [the Jews] with false documents and lodging, with help from the clandestine organization of the C.T.L.N.,” the Tuscan National Liberation Committee.

As we can see, these testimonies seem to fit together in part, but also illustrate overlaps and duplications that seem incomprehensible to us today, while they may have made more sense at the time. They present a picture that deserves a much wider and more thorough study than can be done in this essay.

Most important, the history of false identity cards for clandestine Jews in Florence is filled with great humanity and tragic losses which do not need myths and demand the most profound respect.

Translated from the Italian by Centro Primo Levi. For a bibliography of sources, click here.