Punchy

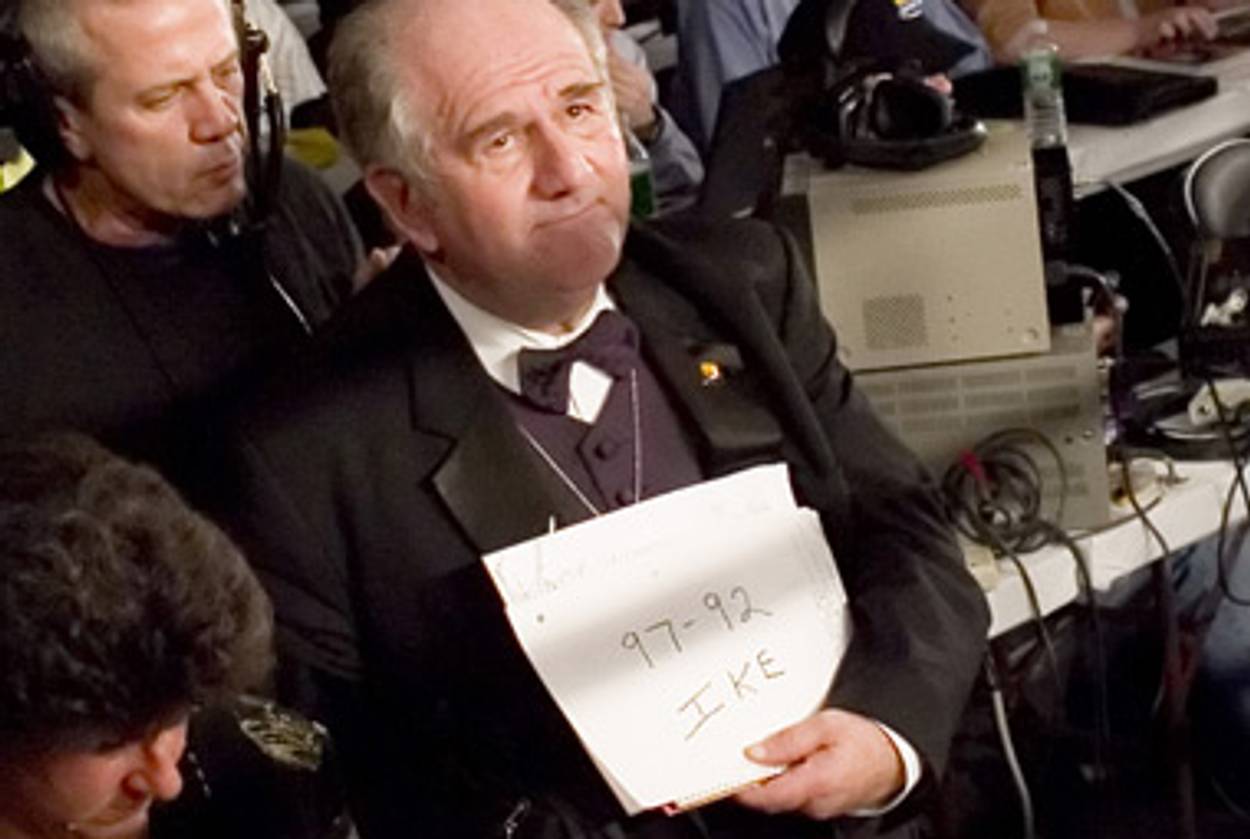

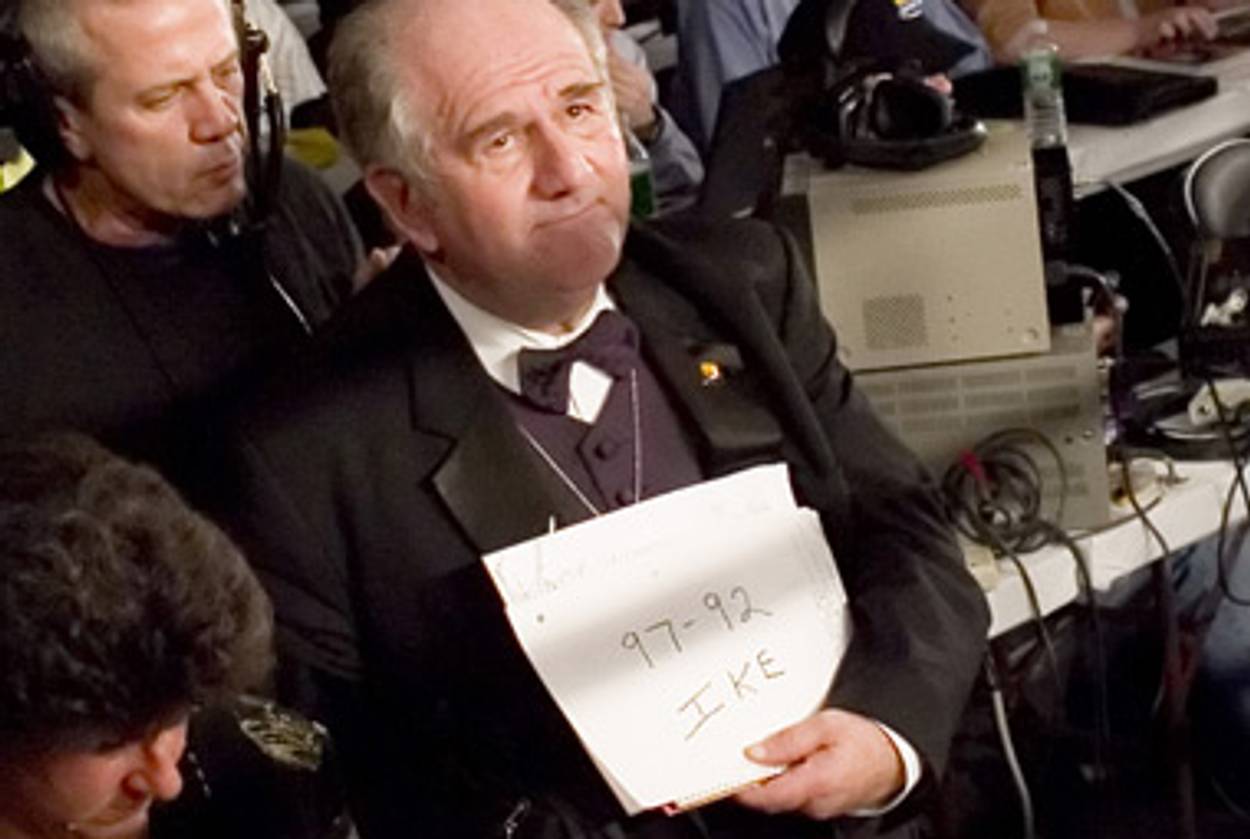

When Amir Khan and Zab Judah enter the boxing ring Saturday night, Harold Lederman will be judging the bout for HBO Sports. With his distinctive Bronx honk, he’s the sport’s most essential analyst.

There is a video on YouTube titled “Harold’s Gotta Tell Ya.” Less than two minutes long, it contains approximately 90 clips spliced together of Harold Lederman saying some variation of “I gotta tell ya” while two boxers duke it out in the ring. Nasal, street-accented, enthusiastic, and high-pitched, Lederman’s voice starts high on “I,” falls a little on “gotta,” perks up a bit on “tell,” and then almost collapses onto “something,” with each word loud enough to be heard over the crowd roaring at the two fighters.

For 25 years, Lederman has been the boxing judge for HBO, the major outlet for professional boxing, weighing in on some of the biggest fights during that time. On Saturday night, he’ll work the unifying junior welterweight championship between Amir Khan and Zab Judah (a Muslim versus a Black Hebrew Israelite turned born-again Christian; gotta love boxing). If a boxing match goes its agreed-upon number of rounds, its winner is determined by a panel of three official judges, who score each fighter on the number and quality of punches landed each round. But those judges’ scores are revealed only after the final bell has rung. Until then, if it is a close fight and you are not a boxing expert, you are in the dark as to who’s up and who’s down. Enter Lederman (the first syllable is pronounced like the metal). His score for each round is posted as the next round begins, and he steps in to explain his reasoning after every third, sixth, and ninth round, as well as immediately after the fight is over. He offers the experience gained from thousands and thousands of fights viewed (since the mid-1940s) and professionally judged (since 1967). “Without question, Harold is one of the really better judges in boxing,” says Don Elbaum, an old friend and a longtime promoter and manager. The boxing journalist Thomas Hauser concurs: “When Harold and the ringside judges earn a disagreement, almost always I think Harold is right.”

Outside this expertise, Lederman, 71, is widely beloved as a mascot for the sport of boxing, a goofy vestige of its good old clubby days. He offers rushes of passion and emotion, like a young child who is so excited to relate a story that he stumbles over himself and can only relate part of it. He’s gotta tell ya! The sportswriter Bill Simmons once imagined Lederman negotiating group rates at strip clubs for bachelor parties: “ALL RIGHT, guys, I worked them down to TWENTY PER PERSON for the cover charge … we have the WHOLE BACK ROOM … we have THREE WAITRESSES … I started a TAB for us, and you can’t touch the girls BELOW the waist!” I can’t prove it, but Lederman was almost certainly the inspiration for the boxing commentator featured in an episode of Aaron Sorkin’s short-lived television show Sports Night, an ancient, eccentric character who only answered to “Cut Man” and who explained of one knockout blow, “It was a right hook, with a bit of a jab.”

Jews are everywhere in boxing these days (except in the ring, of course). There’s Ross Greenburg, who recently resigned as president of HBO Sports, and therefore as the most important person in the sport. There’s Bob Arum, who is the biggest manager (among the many fighters in his Top Rank stable is the sublime Manny Pacquiao). There is HBO color man Larry Merchant, 80, the foremost elder statesman. There is Max Kellerman, 36, an ESPN radio host and HBO color man who is Merchant’s clear successor and who supplies a more nerdy, stats-based approach to the sport. But Lederman is different from them all. It would be an injustice to minimize his formidable boxing genius—he’s no sideshow act—but it would also be a mistake not to appreciate his sense of fun. “Harold is the quintessential fan,” Hauser observes. “He identifies with fans and his enthusiasm is contagious. Harold loves talking about boxing—he’d talk about boxing with a cocker spaniel.”

***

Boxing is Lederman’s life, but it’s not even his career. In his day job, he is a pharmacist, like his father and grandfather before him. Most of his life has taken place within about 20 miles. His childhood was in the north Bronx; he grew up on Pelham Parkway. He spent summer (“summah”) in Rockaway, where his father introduced him to boxing by taking him to fights at Long Beach Stadium, one town over: College was in upper Manhattan, at Columbia. And, now, he lives in Orangeburg, NY, on the other side of the Hudson and just north of the New Jersey border, where he works a day job for Duane Reade, a New York pharmacy chain. When I reached him by phone one evening, he was planning to work the next day at the Duane Reade in the Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center on the Grand Concourse, a 15-minute drive from the house he grew up in. “What I do is, I call ‘em every week and tell ‘em what days I’m available,” he explains in his distinctive voice. “They send me to different stores every day.”

Lederman and his wife, Eileen, who periodically interjects comments into our phone interview based on what she hears him saying, have been married for 48 years. Lederman’s father and grandfather were both Columbia grads. After college, Lederman attended pharmacy school on 68th Street in Manhattan—which is relevant because the St. Nicholas Arena regularly hosted boxing matches on 66th Street until 1962. Eileen’s father was an inspector for the New York Athletic Commission, and he advised Lederman that if he wanted to be a professional boxing judge, the thing to do was to first judge amateur bouts, where there would routinely be 20 fights in one night. Lederman says his favorite fight he ever judged was one of those where he needn’t have been there, a contest in New Orleans between 122-pound champion Alfredo Gomez and a 118-pound comer named Lupe Pintor. “It wasn’t a fight, it was a war,” Lederman recalls with excitement, as though talking about boxing with a cocker spaniel. “In the 14th round Pintor fell down, and Arthur McCanty”—a legendary referee—“counted him out.”

In 1986, Ross Greenburg, a relatively new HBO Sports executive producer, recruited Lederman to be the cable network’s judge for a televised fight, and he realized that he had struck gold. “Pinklon Thomas, a seven-to-one favorite against Trevor Berbick, lost,” Lederman remembers of the heavyweight championship match. “HBO loved what I said on the broadcast.”

Lederman retired from judging when it came to be a conflict-of-interest with his HBO gig. But the name lives on: His daughter Julie is a judge. Last Friday, she scored a 95-95 draw in the junior-middleweight bout between Delvin Rodriguez and Pawel Wolak. One of the two other judges agreed with her, and so a draw it was; her dad, who was ringside as a spectator, also saw it as a tie. “I thought that was a very good decision,” he explains, “cause, boy, those guys were killing each other for 10 rounds!”

***

For all its brutish, and brutal, simplicity, boxing has actually proved quite amenable to the statistical revolution that has conquered so many other sports. A company called CompuBox measures, in real time and with widely acknowledged accuracy, stats such as how many punches were thrown, how many connected, where they connected, and whether they were jabs or power punches. Younger analysts like Max Kellerman discuss a boxer’s punches-per-round and body-shot numbers the way baseball’s sabermetricans discuss a pitcher’s WHIP or a hitter’s OBP+.

Lederman, somewhat surprisingly, turns out to be a fan of new-school statistics-based commentary. “It helps the people at home a lot,” he says excitedly. “It makes the fights much more interesting. I really like the guys that do it. It’s a really good invention: One guy watches one fighter, one guy watches the other, and they press buttons. It’s really a lot of fun, to be honest with you.” Still, Lederman is ever the judge: “No, it doesn’t have any effect on the judging,” he says of CompuBox. What boxing really needs today, he adds, is a strong, charismatic U.S. heavyweight champion. “Unfortunately it’s just dominated by the Klitschkos,” he says of the Ukrainian brothers. “They’re so far and above that it’s unbelievable.”

Lederman got his first shot at the big time—that is, as a full-on color man—for a Saturday night HBO Boxing After Dark only last month. Title card: Adrien Broner vs. Jason Litzau. The result? First-round KO. “Adrien Broner ended my career as an analyst in two minutes, 48 seconds,” Lederman says, and laughs. “It was fun. I’m there if they need me.”

They do. The sport can survive without statisticians, or even another Ali or Tyson. What it can’t survive without are the Ledermans, the old-school kibitzers who can draw in novices with their credible passion. Listen to Lederman once, and you will be sure to tune in to Khan-Judah Saturday night. You may even start scheming ways to watch the September 17 pay-per-view mega-match between Floyd “Money” Mayweather Jr. and Victor Ortiz at the MGM Grand. “It’s not gonna be easy,” Lederman explains happily. “Cause Victor can punch. Floyd don’t like to fight southpaws and he don’t like to fight guys who can crack, and Ortiz can do both.”

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.