Q&A With Art Spiegelman, Creator of ‘Maus’

The influential artist talks about his Jewish Museum retrospective, ‘Mad’ magazine, and how the Shoah trumps art all of the time

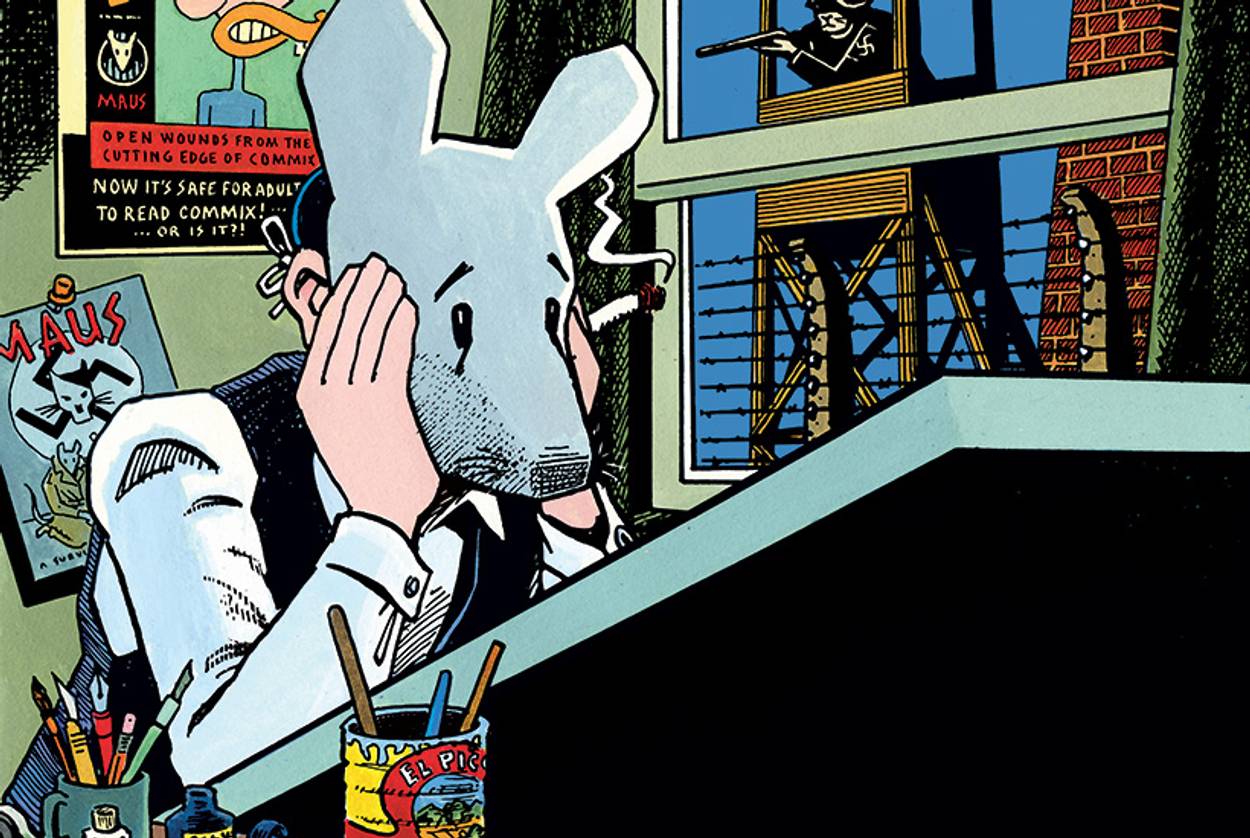

“The Holocaust trumps art every time,” Art Spiegelman repeated more than once at the press opening for his traveling mid-career retrospective, which originated in Paris and finally landed at Manhattan’s Jewish Museum this month. Spiegelman, whose name can be translated as “art mirrors man,” is the owner of a stunningly fertile graphic imagination that over the past 40 years has produced dozens of formally innovative and often searingly self-reflective strips in various magazines, including Arcade and RAW, which he co-founded and edited with his wife, French artist and editor Francoise Mouly. In his day job at the Topps trading card company, he created and edited the Garbage Pail Kid series before moving on to a more upscale day job at The New Yorker, where he tweaked that magazine’s DNA with iconic cover images, including a Hasid and a black woman kissing on Valentine’s Day in Crown Heights and the famous post-Sept. 11 “black cover,” which, when you held it at an angle to the light, showed the outlines of the vanished Twin Towers.

Spiegelman credits Mad magazine and the sensibility of its founder Harvey Kurtzman for shaping his childhood in Rego Park, Queens, and his early desire to use cartoons to express his sense that something was not entirely right with the world. His first Mad anthology, which he studied with the intensity that some of his peers brought to pages of the Talmud, was a gift from his mother, who survived Auschwitz, and he was kept on a tight budget by his father, who also survived Auschwitz. (Spiegelman was born in Stockholm, Sweden, after the war; his brother Rysio died in Poland before he was born after being poisoned in a bunker along with two other small children by his aunt, so that they wouldn’t be taken to an extermination camp.) When Spiegelman was 20, his mother killed herself, and Spiegelman was released from a state mental institution in Binghamton, N.Y., to attend her funeral—an event that would become the basis of one of his early, devastatingly personal cartoons. Spiegelman’s father then burned his mother’s diaries about her experiences during the war and in the camps, which she had intended for her son to read after her death.

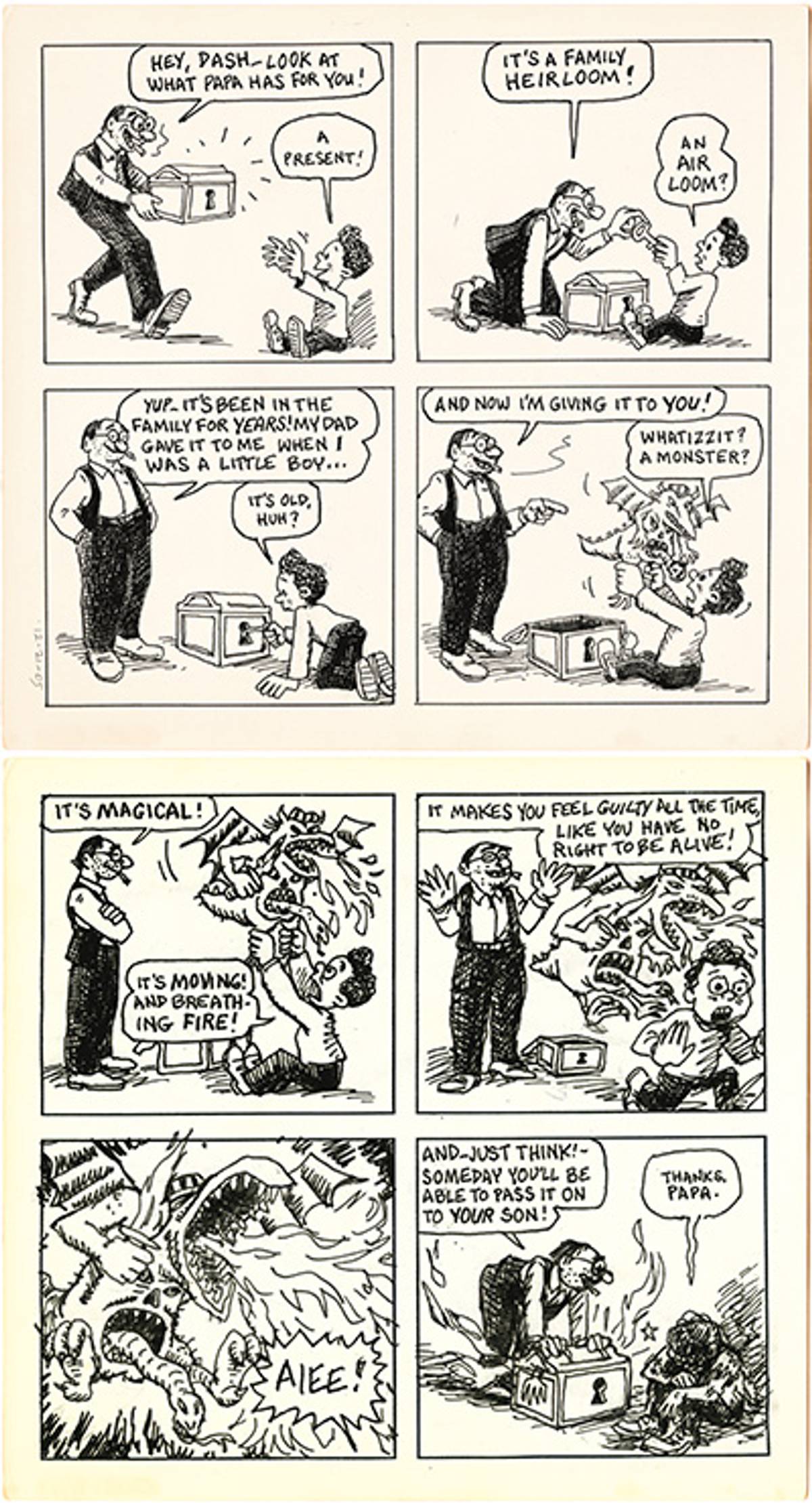

Starting in 1978, Spiegelman, then a well-known underground cartoonist, began interviewing his father about his wartime experiences. In the early 1980s, he began creating strips that narrated his father’s stories and were gently framed by his own relationship with his father, a miserly and compulsive character; the strips were published in RAW under the title Maus. Both the title and the device of portraying Jews as mice and Germans as cats had been used by Spiegelman before, in a three-page strip he had published in 1972 and that was later published in his collection Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, which attracted the deep admiration of hundreds of alternative comics fans but few buyers.

Today it seems clear that Maus and Maus II are the most powerful and significant works of art produced by any American Jewish writer or artist about the Holocaust. While their enduring popularity is a tribute to Spiegelman’s incredible honesty and his graphic and narrative talent, it is also a reflection of the way in which the Holocaust has morphed from a threatening and largely repressed communal trauma to the glue that binds the American Jewish community together. If Art Spiegelman is a genius who created a work of searing originality and insight out of his familial and personal suffering, it is also hard not to worry about the anti-aesthetic consequences of his achievement. If he is right to complain that the Holocaust trumps art, it was Maus that opened the floodgates.

***

David Samuels: I was sitting downstairs waiting to talk to you this morning, and I was watching all the people passing by the hand-inked panels from Maus II, which are preserved safely behind glass in the gallery. And I suddenly had this vision of Maus being preserved for posterity like the Dead Sea Scrolls in some big weird-shaped climate-controlled building on the Mall in Washington, so that future generations of American Jews can remember the Holocaust, which is what we were apparently put here on earth to do.

Art Spiegelman: OK, thanks for bumming me out. Let’s move on.

Does that bum you out? Why?

I mean, I’ve now drawn it 15 different ways—the giant 500-pound mouse chasing me through a cave, the monument to my father that casts a shadow over my life right now. I’ve made something that clearly became a touchstone for people. And the Holocaust trumps art every time.

Well, there’s that, sure.

I’m proud that I did Maus; I’m glad that I did it. I don’t really regret it. But the aftershock is that no matter what else I do or even most other cartoonists might do, it’s like, well, there’s this other thing that stands in a separate category and it has some kind of canonical status. It’s what you’re describing with your Dead Sea Scrolls analogy. It’s been translated into God knows how many languages, it stays in print, it’s a reference point. So, when I’m reading some movie review in the Times about 12 Years a Slave, all of the sudden I’m seeing a reference to Maus, even though the subject matter is quite different. It’s studied in schools from the time they’re like in middle school to the time they’re doing post-graduate work.

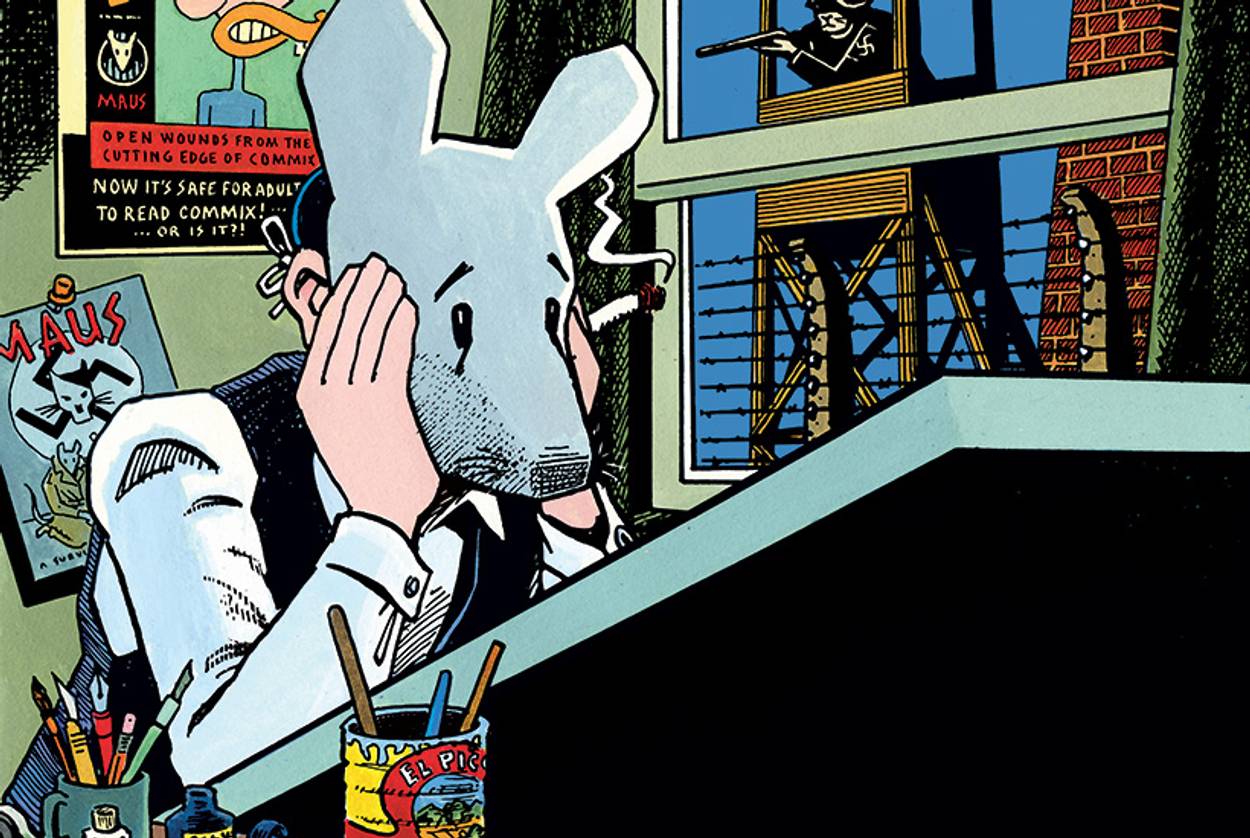

There was that great strip that you did for the VQR, where you were handing a little treasure chest to your son Dash, “Hey, here’s this wonderful magical present”—the gift being historical memory—and he opens the box and this horrible fire-breathing dragon comes out in an Auschwitz striped prisoner’s cap with a little extra Hitler head and breathes fire on him and burns him. And he’s like, “Gee, thanks, Dad.”

It’s one that you can’t deal with and then move on easily. I remember Claude Lanzmann at some point saying Shoah ruined his life.

Except he wanted his life to be ruined in that way.

Yeah, but I don’t know if I wanted it or didn’t want it. It wasn’t part of my operating system. I wasn’t thinking about it.

Right, and that’s what made Maus so different and effective as art, that feeling of absolute sincerity in an unexpected form. But if I wanted to really bum you out I’d say that some huge part of the genius of postwar, American Jewish art took some energy from the repression of that monster that you let out of the box. You can read all of Philip Roth for a long time until you get to The Ghost Writer, you can read Bellow, you can read Joseph Heller, and look in vain for any mention of the Holocaust.

I just watched on Netflix the Salinger film a few days ago, and all of the sudden, Dachau is the codex for Catcher in the Rye.

Right. Except, he never wrote a book about being a young American soldier in Dachau. He wrote a book about a preppy kid riding the carousel in Central Park.

Evidently he married a Nazi, and it’s the subject of one of his unpublished manuscripts that’s going to come out in the next five years or something.

So, it turns out that J.D. Salinger was writing his own Glass family version of Maus up in Cornish, N.H., in addition to eating sunflower seeds, or whatever else he was doing up there.

I don’t think his drawing is good enough to do it as Maus. What am I going to do? Say I wish I didn’t make Maus? That’s just not true. And on the other hand, do I want to have it dogging my steps everywhere? I’m going to say I’m lucky that it does, because it allows me to enter one folly after another and still make royalties from something else.

But what does it mean for me now at this point? Look, my cells have replenished themselves several times over, and it is what it is, and I did everything I could to tithe to it, to give service to it, by making MetaMaus, which is more easily accessible for most people than having to come to a room in the Jewish Museum. I guess it all reminds me of Joseph Heller’s response to being told no matter what he did afterwards, “Well, it’s good but it’s no Catch-22,” to which he said, “Yes, but what is?”

But it’s an issue because I’m not dead yet. So, I have to keep moving as best I can through the shadow of something that I’m glad I had pass through me.

That’s a very graceful, healthy, well-processed answer. And there are two directions that I want to take that. The Pew Foundation just did a big study on American Jewish life, and who American Jews are, and what they think makes them Jewish. And the No. 1 answer that the respondents gave about what being Jewish means was “remembering the Holocaust.”

Now, I loved my grandfather, he was the person I felt closest to when I was a child, and he was the only member of his family to survive the war, and I grew up in a community with lots of survivors. So, the aftershock of those terrible experiences was definitely passed on to me and kids in my generation, even if it was outside our full awareness. And I wouldn’t wish those effects on anybody, you know? So, it’s interesting to see the American Jewish community choose “remembering the Holocaust” as the touchstone for its sense of communal purpose. American Jews are people who remember the gas chambers in Auschwitz.

We are here to carry on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and Harvey Kurtzman, as far as I’m concerned.

Inevitably, this specific odd and intense cultural burden of carrying forth the near extinction is also something that Jews have a responsibility to do. And the problem for me, its most thorny place, is when we start thinking about the existence of Israel. If you wanna, since it’s Tablet, we can go there.

Go ahead.

For me, it’s sort of like, “OK, Zionism existed before the Holocaust—but the Holocaust is the broken condom that allowed Israel to get born.”

So, at that point, what are we remembering when we remember the Holocaust? Are we remembering that Jews specifically have to do whatever is necessary to ensure their own survival at the expense of others, who share a large part of our common DNA?

That seems like a very pleasant humanistic lesson to pass on to one’s progeny, no?

The thing you can remember is “Nobody ever liked you, they’re not going to like you, so fuck ’em. And therefore Israel is going to do whatever it has to do to survive, by God.” Or the other lesson could be, “We got shafted because we were a landless people without a power base and therefore, what? We create another landless people without a power base?”

Fuck. I mean that doesn’t seem like the best lesson to learn from the larger cosmos of what Maus grew out of. In the first 3-page Maus, if you look at it downstairs, there are no references to Jews, and no references to Nazis per se, although clearly it underlay the entire project.

‘The Holocaust is the broken condom that allowed Israel to get born.’

At that point, very specifically, I was dealing with this from a very secularized notion of what it was to be oppressed in a political system. That’s what it meant to not talk about Jews and Nazis. It grew out of thinking about the black situation in America, which is why it’s not totally divorced from 12 Years a Slave. I didn’t see that one coming, but I get it. It depends which lessons you choose to extract and move forward with. One is potentially useful because it increases one’s empathy factor, and one is dangerous because it increases the ways in which you defend your little corner of the DNA empire from all others.

I think the narrative that “Oh, Israel was born out of the Holocaust and never forget and whatever” was very popular in the U.S. at a certain point, particularly in Queens, where you grew up and in Brooklyn, where I grew up. I get the sense from my family and friends in Israel, though, that they were completely uninterested in the Holocaust when the state was created, and for a long time after that. I remember having lunch with the Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld, who in my opinion is perhaps the greatest living Jewish writer anywhere, who survived the Holocaust and emigrated to Israel. He told me that when he came to Israel they called the refugees “savonim”—soap people. The ones who were going to be made into soap by the Nazis. The Holocaust didn’t really fit with the proto-Soviet realist aesthetic of sturdy pioneers with muscular asses working the fields, and all that.

Yad Vashem wanted to show Maus. And I was going like, “Oh God; do I have to do this, I don’t want to do this.” Talking about your Dead Sea Scroll vision, you know.

I imagine it in the Holocaust Museum in D.C., in its own special wing, you know?

There was a point when we were talking about having Maus in the Holocaust Museum, and I was much more interested in seeing something about the former Yugoslavia and genocide now. So, that’s the tug of war that I’m talking about.

I don’t know how to respond to the prewar sabras and their vision of Zionism. I just don’t think that Israel would have come into existence without the Holocaust happening in the world, because I don’t think that the Balfour Declaration of 1917 or whatever would have held up that well without it. The world wouldn’t have cared.

I think those guys were tough and ideologically driven, and they were set on their goal of establishing a Jewish state. This summer, I interviewed Shimon Peres, the current president of Israel, and I asked him, when did you find out about the Holocaust? And he said, “Well, after the war, you know, when those people came.”

At least he didn’t wait to read Maus.

I was like, “What was your response?” And he told me, “Well, you know, we went to Poland in 1945,” and then he started going into a long discourse about how Golda Meir was trying to undermine him at the time with David Ben Gurion, or whatever—my emotional translation of that story being that he actually didn’t care about the Holocaust, because he was so wrapped up in the political infighting among this hothouse group of people who came to Palestine when they were 15 and were building a Jewish socialist-collectivist mecca in their own imaginary version of the Middle East.

I understand all that but, you know, it used to be when I was first out and talking about stuff, I would actually have horrible arguments when people were talking about Maus, even when it was still not published as a book yet and when it was first published as a book in which somehow anything that had to do with Israel had to be supported absolutely. That’s changed since 1983-4-5, and now radically. So, now it’s impossible to think of these things as disconnected. Whether they want to talk about it or not, something happened. And what happened was the world’s agreeing that, “All right, so you didn’t have any place, and we saw how well nationalism worked on the planet, so rather than trying to like move beyond it, let’s give you a nation! Let it be.” And from that moment on, certain things started happening. Parenthetically, I’m amused by Chabon’s really great Yiddish Policemen’s Union book.

The frozen chosen.

There were a lot of alternate universes in which people are trying to figure out what the hell to do with the Jews. We’ll send them to the tundra, we’ll send them to Madagascar, depending on who was deciding on the real estate for us. And one of the possible places was Palestine, which in a way is an absurd place for it all to exist.

What little I found out about the secret origins of the superheroes of the Jewish nation is that it was itinerant salesmen back in the Babylonian days who planted their seed and said, “You’re in charge of giving these kids religion, and it’s Jewish. OK? Gotcha, I gotta go somewhere else now, I’m an itinerant.” And this gives you a lease? Probably, I don’t know, but that seems pretty sketchy to me.

So, what there is now is there’s this inevitable thing that came with the trauma of WWII for the world’s Jews, clearly. That led to something kind of interesting, which is—I can’t quite say it. I tried to say it when Tony Kushner was putting together a book about American liberal responses to the Jews. He asked if I would do the cover because I was doing a lot of these New Yorker controversial covers, helping that become part of the DNA of what The New Yorker now is. But at that time I said, “Look, I don’t want to do a picture inside the book, man.” It’s great, but I’m so tired of having to submit work and see if it would pass for people and then having to submit work and see if it will pass, and then having to defend the work. So I said, “I can only take this on if you’ll give me a blank check. I’ll do it, you’ll run it. But you have to know that up front.”

And he said, “Uh, I’ll have to check with”—I don’t remember who the publisher was—“and see if that’s OK.” I said, “Fine.” Then he said yes, and then I came up with an idea I really liked and then I thought, “He’s a really fine fellow, that Tony. I really admire him. I like him. I don’t want to give him any grief.” I got only as far as getting the idea and making the very first sketch that had some photo-collage elements and whatever. I said “Tony, I know we’ve got a deal, but I’ve decided I’m not going to hold you to it. So, here’s the sketch, tell me if you want it. It’s going to be a pain in the ass to paint, it’ll take me a couple of weeks, if you want it it’s yours.”

It was a close-up based on the same famous Life magazine photo that was at the start of the 3-page Maus: Palestinians behind barbed wire wearing Jewish stars. In front of the barbed wire was an Israeli soldier with his gun and also with a Jewish star, and he’s also behind the barbed wire and looking mournful as well. And the implications of it are unbearable for a lot of people, it makes their heads explode. Still.

That image was all I could say. Because it was fortunate enough for my parents went to the right rather than to the left in that line, and they ended up here, and so I don’t have to bear the burdens directly of Israel’s culture. So, that image just has to do with the fact that it’s victims victimizing each other, damn it. Here we go again. And there’s a responsibility that Israel doesn’t live up to, and it drives me crazy.

I hear you. But I’m a first-generation American who was born in Brooklyn. So, while there’s something interesting about these American Jewish narratives about Israel being all good, or else bearing some special moral responsibility for extra-good conduct that it spectacularly fails to meet, both those narratives seem a bit weird to me. There’s one group of people who has a cartoonish vision of Israel as some beleaguered innocent state. And then there’s another group of people who seem to say, “Well, of course, if it’s going to be a Jewish state, my demand is that it should always be perfect, or otherwise it shouldn’t exist at all.” My personal feeling is that Jews, in some deep way, aren’t inherently any different than Armenians or Serbs or any other of these tribes with long histories, all of which interest me aesthetically and historically. But I personally don’t see Israel as any more intrinsically good or bad than France.

Or America. But Israel’s history went on for a very short time, which is the flip side of the same answer. It was born when I was, and it thereby is more directly discomfiting than when I drive around Monument Valley and see what’s left of the Indians, even though that’s pretty horrible. I somehow go, “Me, I’m a stranger here myself. I didn’t do this, it’s terrible, I agree it’s terrible.”

But that’s slightly viscerally different to me than when somebody snarls at me because I’m Jewish, even though I haven’t a religious bone in my body. And yeah, at that point the cultural heritage of what brought me here comes into play. And that makes me more able to tap my own guilt than even when I get to see 12 Years a Slave and get to feel guilty about what I did in the slave trade.

The historical ‘I’ that is a white male Southerner, circa 1850.

Right, but here I am as a white male in 2013 living with the fruits of that exploitation, as well as the guilt and horrors that come with that 19th-century slave trade. And I don’t know what to do about any of it. I was born a Jew in Sweden.

All I can say is I’m really glad I’m a diaspora Jew. I don’t identify with Israel. I’ve almost gone several times as an adult—never, always bailed at the last minute. If I go I’m going to mouth off, and then I’ll get myself involved in some project I don’t want.

There’s a thriving Israeli left, they spend their time mouthing off, and they get a lot of money from foundations for doing it. I guess my personal posture on these big issues is “Hey, I grew up in a housing project in Brooklyn, I didn’t oppress black people in the South, I didn’t kill any Palestinians in Israel, so I’m happy to talk to anybody, as long as they are being cool with me.” And if they’re not, my interest wanes.

Yeah, it’s just it’s inevitably part of anything that comes out of that Maus book that I end up having to at least think it through, because of what you were saying to start this particular gambit. And that has to do with the fact that the primary thing that defines one’s Jewishness unfortunately is not Groucho Marx. It’s the Holocaust.

I remember when RAW first appeared, I was in high school in New York. And it was just one of those touchstones of cool if you had a new copy. That’s like the way high-school kids used to read that stuff, it’s just like it’s sacred. And it was great. I remember the fact that someone had turned the Holocaust into a cartoon strip, and that the Jews were mice and the Germans were cats, I remember thinking, how did he even get on top of all that shit, which none of us could begin to imagine except in the ways that it was given to us, as something that was too big to imagine in anything but the accepted ways. It was just like, “Was the person who did this evil thing, is he a genius?” It was the total coherence of that gesture, like Cubism—

That’s interesting, ha.

And the emotion in it, and the drawing, and all of it. Growing up in a Jewish community here, it felt like the ultimate Samizdat. We didn’t even know, like do we bring this to our teachers and ask them if it’s good or bad, because what if they punished us, or, even worse, what if they liked it?

Now we find out, they seem to like it. I know we’re talking about only the middle part of the exhibit that I’m grateful to have it, because it has the two other parts. But we’re talking about the middle part.

And this is your life now that you created Maus, and you have to sit in well-appointed conference rooms with people like me and go over and over that.

But you know you’re the first interview where this was true. Because you’re Jewish. They might be Jewish too, but they at least came from a different set of perspectives where I am not trapped again in this same conversation.

So, maybe it is me. But I was going in a completely different direction now, which is depressing in a different way. I think that part of the power of your original gesture was that there was still this feeling of resistance in the culture. There was something that you could push against. The thing that I feel now is that spirit has been diced and tamed and put through some kind of food processor. I don’t find the places where the culture blob doesn’t engulf whatever it is in three minutes flat.

‘The Simpsons,’ ‘The Daily Show,’ ‘Colbert’ are among the healthiest aspects of American culture right now

This can actually bring me back to my Groucho Marx moment here, or pivot, which has to do with the Groucho Marx and Milt Gross and Harvey Kurtzman legacy, which was an incredibly important one. Now, if you’re talking about nationalism, then you have to get to Duck Soup within a couple of seconds. And that impulse predates WWII, and it’s an outsider’s perspective on a culture, and there are still plenty of outsiders to this culture, and things will come from that still, I believe. That’s one point.

The other point, which is more to the point perhaps, is the impulse—I see it through Mad, because it’s the one that’s imprinted on me. Mad made the resistance to the Vietnam War even possible. And that seems really, deeply true, not just some kind of wise-crack true. Because the ’50s felt incredibly monolithic. The early ’50s was an incredibly oppressive place in America, very iconically represented by a decent-enough liberal chap named Norman Rockwell. It’s when we got this ‘In God We Trust’ on our money, it’s when we had our crazy McCarthy moments, we had all of these things happening, and yet there was room for a very effective antibody, which was this kind of self-reflexive, self-deprecating, angry response to the homogeneity from people who weren’t thoroughly homogenized in our culture, i.e., Jews. It led to something very fruitful, and we still have the aftermath of it, both positively and negatively.

Positively for me, I would say, The Simpsons, The Daily Show, Colbert are among the healthiest aspects of American culture right now. And they have to do with carrying the genuine legacies of the earliest Mads forward.

There’s another thing that happened as a result of any antibody becoming weaker after a period of time like now that all our cows have antibiotics in them we’re not as good at fending off all of the diseases. Similarly, the Mad impulse of irony has been reduced to the air quote, and the self-reflexivity is everywhere in the culture. It starts in the spin room, and spins on out. And the spin room is about spinning us as viewers of news, it’s not about deconstructing news, it’s about enforcing the takeaway messages, right?

So, I felt that like, now we needed something else, and for a while I was just calling and now I’ve dropped it, it was a particular thing I think about a lot. But I was thinking, we needed this thing that I was calling “neo-sincerity,” which was involved with specifically using the tools that Mad offered but only in the pursuit of absolute conviction. And that that was the only way to get back to a place where you could tell where people were coming from and figure out what actually has value and is important and can’t be reduced to the ironic Letterman shrug.

Yeah, a lot of writers my age came to that conclusion too. Dave Eggers was certainly one. And lots of smart people tried it, but it was like, you know in a way, all those nice liberal people from the ’60s have become the Eisenhower Americans of today, except they vote for Democrats. They’re the baby-boomer grownups of your generation, and in some ways they are more dangerous. Because they always have just enough sympathy with whatever the gesture is, and they smoked pot too, and they dropped acid back in the day, and they go, “Yeah, yeah, yeah we like that and we’ll appropriate some of it, but then please don’t do this other thing that you just did, because it’s just too transgressive and messy and gross.” And it’s like, they’ve already let you in the door and are paying your rent, so please don’t do that yucky cover you wanted to do.

There’s that. But there’s also the fact that even if you get to do the yucky cover, it’s like what was the really great metaphor from a Kafka story about leopards? The priests have a ritual, then one day the leopards show up and eat all the priests, and then they resume the ritual the year after, including all the leopards. It’s an amazingly resilient and resistant culture, capitalism. And we’re the beneficiaries of it, so we’re not about to go to the barricades and set fire to our own houses. But then what?

If Jews carried that oppositional torch for a while for particular historical reasons in 20th-century America, the truth is that Jews are just another group of rich white people now. They’re not outsiders, but they go on believing that they are still outsiders, raging against the machine as part of their secular religion of being good empathetic liberals. And at a certain point, it becomes silly.

It’s a condition of outsiderness that we can build on. That’s all we’ve got. Because the alternative is to become a Madoff or something, I don’t know.

I think the alternative is to own up to being WASPs.

Oh, WASPs don’t get to complain, so I don’t think I want to go there.

Maybe Jews can be the new complain-y kind of WASPs.

Maybe the new complain-y WASPs.

I think that there’s something that gets eroded, which is, you know, that outsider thing obviously doesn’t happen as easily once you’re inside. It gives me reason to pause and worry about what it is that keeps driving me. And because I don’t see where anyone can actually find a place to pry at, that pries it all open.

I could say that, there was a minute there where Occupy Wall Street was the only positive thing I saw in the culture. And it was amazing how easy it was to watch it evaporate and get pushed to the sidelines with the first rainstorm. We have it in the corner of our ears because of one slogan that survived, that moment which has to do with the 1 percent, but it was a useful moment to enter in, despite everything that didn’t happen. And as little as that is, it’s still a step in the right direction, to notice who has got the cards.

On the subject of cards, maybe the moment is right for you to go back to the Garbage Pail Kids.

They’re still being done.

I feel there’s a re-imagining of that imagery for the era of Facebook and Twitter, which are the new untouchable toxic brands.

I’m sure that will be done, and it sort of exists without it being homogenized. There are artists who are working off of that energy because they were at the right age when that thing happened. Were you? You were a Garbage Pail Kid fan?

I used to buy them sometimes for my younger brother. He really loved them.

A lot of people are imprinted with them, and it made a difference. I thought of it very consciously as taking my Mad lessons and passing them along dutifully to the next generation. And there I must say, I made sure that the title cards at least in this show were clear about what parts I had to do with and what parts I didn’t have to do with it. I didn’t paint those things, I planned them.

It was an intervention, as the French people say. Yeah.

Now it would unfortunately just be more leopards coming into the ritual. Because that existed, now what’s next; I’m sure we’ll find out, you know?

Is that a problem for culture? If you look back at the stuff that I was raised on, whether it was little ’zines or it was RAW or whatever, that stuff was actually hard to get. You had to go to a specific store somewhere weird to find it. And people had to stew in their festering little pool for a while, until you got desperate enough to visit someone else’s pool and risk them making fun of you and the clothes you wore.

I think that that’s an issue at this point. Everybody can sit in their own stew, they never visit the other stews. And the fact is that nothing is hard enough to get so you concentrate. The main thing that the Internet seems to have given is Attention Deficit Disorder to an entire culture, and I include myself. I don’t stand aside and say “Tsk, tsk, these young people with their computers.” But I don’t see exactly where things move, which is why I’m still thinking about Occupy Wall Street because their resistance to being co-opted allowed them to be wiped out as a force. And it’s such an estimable gesture, while it’s also so pathetic.

[The gallery assistant comes in to signal that the interview is over and asks Spiegelman how it went.]

Wow, OK. We didn’t talk about anything but Maus.

Gallery Assistant: Well, I only hear the very ends of interviews, but you end with a bang every time.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.