Bound for Glory

The Israel Museum unveils a restored mahzor from 1331

Central to the Days of Awe in modern times is the experience of walking into the synagogue to find tall stacks of High Holiday prayer books, or mahzorim.

Things were not always thus. For centuries, Jewish prayer was an oral tradition, said from memory. Even as authoritative liturgies were codified, most didn’t have access to texts. Rather, manuscripts—by definition handwritten and unique—were created for communal use, with myriad variations according to local rites. Some of the wealthiest may have had smaller, private copies, but, for the most part, congregations either chanted prayers from memory or repeated after a cantor. Not until Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the early 1450s did books become accessible to a broader public, and for some time they remained a luxury.

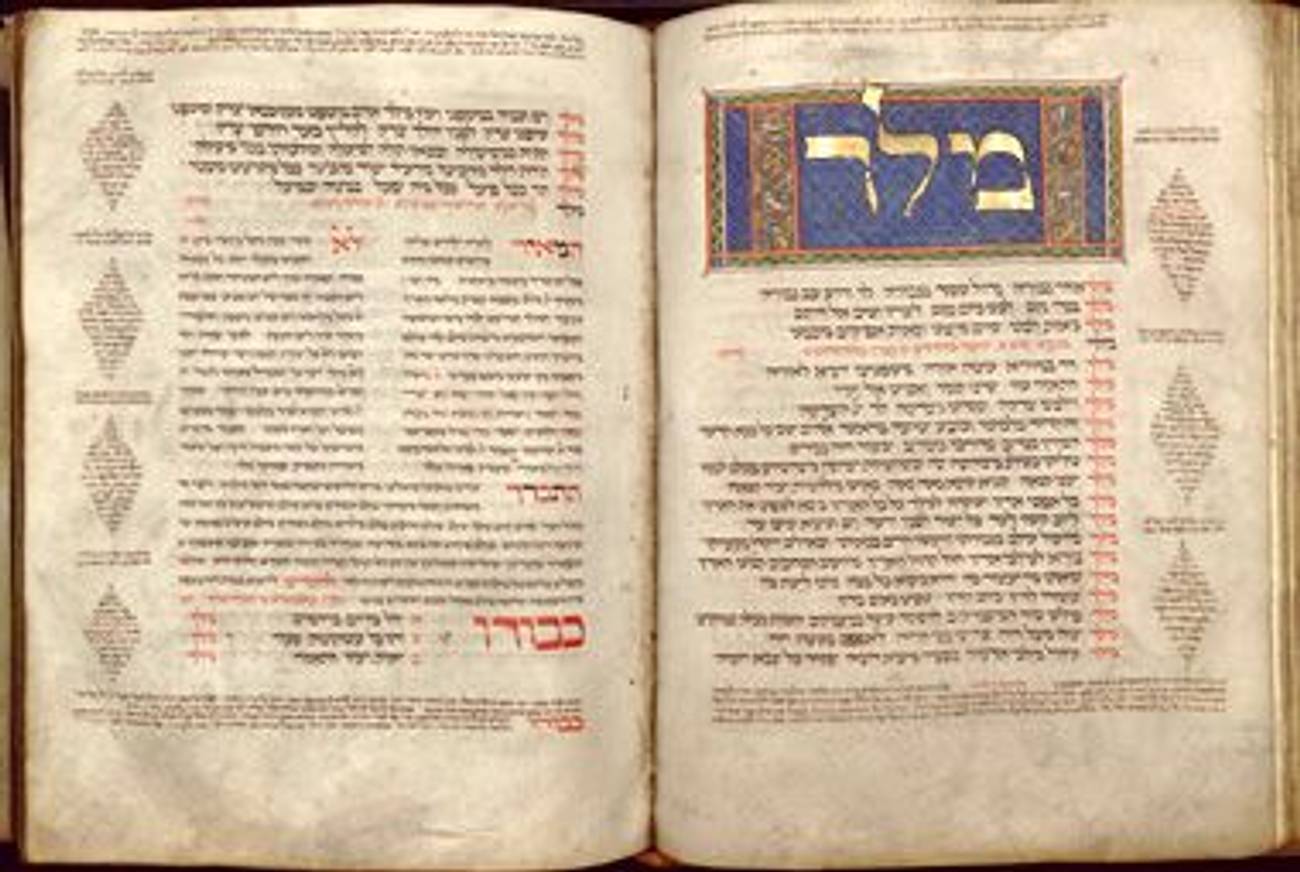

But even within the unique realm of early prayer books, the Nuremberg Mahzor, which has just gone on public view for the first time in 52 years at the Israel Museum after a nearly year-long restoration, is exceptional. Completed in 1331 for the Jewish community of Nuremberg, the sumptuously decorated work is not only one of the most comprehensive illuminated Hebrew prayer books ever created, it is also among the largest medieval codices in the world.

Weighing more than 57 pounds, it is made up of 521 double-sided leaves. It includes holiday prayers for the entire Jewish calendar; the five books of the Bible known as the megillot, or scrolls; special prayers for lifecycle events like weddings and circumcisions; extensive commentaries; and—its main feature, accounting for roughly 90 percent of the text—over 700 piyutim, or liturgical poems. Moreover, the quality of the scribal work and elegantly embellished panels qualify the text as one of the region’s outstanding manuscripts. While communal mahzorim were also created in Spain, Italy, and other Jewish centers at that time, this monumental format was a phenomenon particular to the Franco-German Ashkenazi region.

Equally impressive is the work’s provenance. The colophon at the back indicates that it was commissioned by a Joshua the son of Isaac and completed on the fourth of Elul in the Hebrew year 5091. It remained in Nuremberg after the Jews were expelled from the city in 1499 and was preserved intact at the municipal library until the early 19th century, at which point, it is assumed, the Napoleonic army excised 11 of its original 528 leaves. More than a century later, the renowned publisher and Hebraica collector Salman Schocken embarked on a quest to reassemble the Nuremberg Mahzor and bring it to Israel. He recovered four of the missing leaves in the 1930s after fleeing Nazi Germany and acquired the rest in 1951 as restitution for assets that had been confiscated from him during the Holocaust. Descendants put it up for auction at Sotheby’s Tel Aviv in 2002, where it carried a $2-3 million estimate but failed to sell. At some point afterward, it was acquired privately by the Zurich-based collectors David and Jemima Jeselsohn, who have given it to the Israel Museum on extended loan. Through February 2010, it will be the centerpiece in the Shrine of the Book, home of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The restoration, conducted by Michael Maggen, head of the museum’s paper conservation laboratory, focused on rebinding the manuscript and incorporating the four recovered leaves. Overall, the mahzor was in excellent condition. “The decoration and writing looked like they were practically done yesterday,” according to assistant Judaica curator Anna Nizza, who adds that the colors and gold leaf “were amazingly preserved.” The highly skilled scribes who worked on the main text and commentary—identified as Mattanyah and Yaakov, respectively—made almost no errors despite the work’s considerable size. They also masterfully executed simple but sophisticated flourishes while leaving precise blanks around key words for, it is assumed, a Christian artist to subsequently decorate. (Jews were closed out of guilds at that time.)

Rather than iconographic subjects, human figures or narrative scenes that populate other significant 13th- and 14th-century mahzorim, the Nuremberg features 22 illuminated panels highlighting introductory words. These frames are adorned with gold and silver leaf and precious pigments, notably in rich hues of blue and red, and decorated with geometric patterns, as well as foliate motifs and exotic animals, typical of Gothic imagery. The scribes also alternated the size, type and color of the script—between black and red throughout. There is only a single text illustration, of a shofar, next to a line in a Rosh Hashana piyut about the sounding of the ram’s horn. “Unlike their contemporaries,” Nizza explains, “they chose ornamental and non-illustrative depictions, giving the manuscript an aesthetically pleasing and elegant look emphasizing its content while helping the chazan find appropriate prayers during the service.”

Jeannie Rosenfeld, a Tablet Magazine contributing editor, writes about fine and decorative art.