Reliving Tragedy Was My Job at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum

How under the weight of history, all memory becomes holy—even the memory that should not

I spent my first day as an Oral History intern at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum throwing up between meetings. I was jetlagged and sick from the summer humidity, a sickness that would stay with me until the weather changed in October. I sat in boardrooms sweaty and flushed and listened to various museum directors go through mock-ups of the exhibitions and introduce the materials we would be working with. Over coffee and glazed donuts they played us the recordings that visitors would come to the museum to hear. We listened to the voice-mails Sean Rooney left on his wife’s phone as he watched the fire in the North Tower. The air-conditioner buzzed as they explained that the time stamp on the last message put it at one minute before the second plane crashed 25 floors below him into his building. They told us that Sean was on the phone with his wife when the South Tower began its collapse 56 minutes later and that in 2009, after eight years of dedication to Sept. 11 widows’ advocacy groups, Sean Rooney’s widow died in a plane crash in Buffalo. “Working here is hard,” the exhibition manager said. “You don’t know when it’s going to hit you. It might be tonight, it might be tomorrow, it might be in three weeks from now. Don’t feel shy about taking time out for yourself whenever you need it.”

I tried to nod and smile but feared that I would throw up again. The carton of donuts was untouched except for one a tight-lipped girl had taken at the beginning of the meeting. The other interns looked ashen-faced and showed signs of a tiredness around the eyes that by 5 p.m. we all would share. I watched the tight-lipped intern look down to her half-eaten donut and wondered how long I would have to wait until it hit me.

When I left the air-conditioned office, early because I was ill, and walked out onto the intersection of Liberty and Broadway I thought how it could be that I had never felt humidity like this before.

***

I fell into Oral History the way anybody falls into anything: I was hungry. It was 2008, two years before I would accept the position at the September 11 Museum, and I was a sophomore in college. I had quit my position as a telefundraiser and, after week 3 of boxed macaroni and cheese, too proud to call home and ask for more money, I decided to look for a job. An online posting led me to the Columbia University Center for Oral History.

Mary Marshall Clark, the director of the center, provides this definition for those unfamiliar with the field: “Oral history, a multidisciplinary methodology in community arts and cultural development and an academic field bridging the humanities and the social sciences, offers a powerful alternative means of both documenting and disseminating human experience by allowing people to construct their own life story.” Columbia is where Oral History as an academic discipline was invented. Founded by Allan Nevins in 1948, the office contains one of the largest Oral History archives in the world, the individual collections ranging from Argentinean politics to the history of the Apollo Theater, to the Koch Administration and Female Iraq War Veterans.

In the weeks following Sept. 11, 2001, Clark began to enlist a broad force of interviewers to conduct a large-scale urban oral history of the attacks. The initial concept was to collect interviews from those with distant and proximate experiences of the days, survivors and witnesses, particularly those from Latino and Arab communities, and to create “life story interviews before ‘official’ versions of the story defined by the media, government, and private and public institutions take hold.” The men and the women recruited ranged from psychologists to journalists, from trained oral historians who had worked with the Shoah Foundation to master’s students who had just learned to use their recording devices. After a brief and mumbling interview with Clark, I had a part-time position as an editorial assistant, a position I would keep for the rest of my undergraduate career, overlapping with my time at the September 11 Museum.

The Center for Oral History was small and open. From any given corner, you could see nearly everyone’s desk. You could see if they were working, if they were on their phones, if they were on a website that they shouldn’t be on. But for all its intimacy the office was surprisingly soundproof. Voices from five feet away didn’t carry. We worked, in plain sight, in silence.

***

In order to prepare for the Memorial Exhibition, the portion of the September 11 Museum that is intended to individually commemorate the victims of the 2001 and 1993 World Trade Center attacks, the museum created an intra-departmental program called Memorial Connections. Each day a staff member was given the names of five or six victims. That person was then responsible for the verification of the victims’ name, age, birthplace, primary residence, career, and location on Sept. 11 as well as the compilation of any online records, such as commemorative websites, local obituaries, and, of course, the long-running New York Times Portraits of Grief.

This responsibility was a tedious one. The Memorial Connections had been going on for over a year and continued for the duration of the year I spent there. They arrived each morning in an office-wide email sent by the receptionist. Few actually took the time to navigate the site or even do the work when it was assigned to them. Most people submitted their names late or tried to pawn the task off on interns in their department. No one on staff needed to be reminded of the infinity of the victims. No one needed to read another trite biography. No one needed to see another picture.

I skimmed through the New York Times’ Portraits: 9/11/01: The Collected “Portraits of Grief.” I was looking for someone specific, a man I found in Memorial Connections when I started at the museum and hadn’t been able to stop thinking about. I remembered his face, chubby and blond, round glasses that he had probably worn for more than a decade. He was a passenger on one of the flights, I remembered. He worked as an engineer—or maybe at a university. He may have liked motorcycles or model planes or Dungeons and Dragons, I couldn’t remember, I just thought he seemed like a dork. I searched all the terms I could think of online, through every Memorial Connections email, I couldn’t find him. I flipped through, page by page. A face caught my eye—it couldn’t be him. His name might be Jared, Seth, or maybe Brian. I wondered if I would recognize him if I saw him. I knew that I would. I went through the R’s, the Q’s, the P’s. I began to wonder if he existed in the first place.

I remembered staring at his happy round face, the “Digital Portrait Relating to Victim Last Name, First Name” on the museum’s database. I remembered that his eyes were half closed, and I wondered who decided that was the best picture of him to be remembered forever in the museum’s archive. He had a website in his memory. He had no wife or children, but he looked so happy. He almost made me mad, and then I remembered that he was dead.

***

There are the moments when you intrude on a situation that you know you should not be a part of. Then there are moments of tragedy, moments of survival, moments of condemnation, and moments of pre-emptive failure. And then there are moments in which we look for too long at something that we should not: the man asleep on the subway with one leg; a dirty picture; bodies that jump 110 stories to the ground.

Several months into my internship at the September 11 Museum, I sat in the office and my ears were numb from wearing heavy headphones. Jeff Johnson, a firefighter who survived both tower collapses in the World Trade Center Marriott, was describing the sounds of the jumpers after the second plane hit. It had taken me four hours to transcribe his 60-minute interview. I could not listen anymore.

At the desk in front of me, the media intern was on hour 6 of her daily 7-hour dose of documentary footage that her job was to time stamp. I heard words while she stared at the smoking towers and followed bystanders running in the street. That day her screen was the view from someone’s apartment, the camera watching the second plane glide gently down into the South Tower. I looked over her shoulder.

One day after work I ask her if she has dreams of the smoke formation that sprouted from the burning towers before they fell. I say that the smoke came out at such a distinctive angle, she must see other things that follow that path and think of the towers.

“I don’t know,” she answers. “Do you dream in voices?”

I don’t dream in voices but I do spend a lot of time wondering what I would say in my own oral history if I had been there. There are some sentences that are so perfect I know I could never have come up with them myself. I wonder if I had been in New York on Sept. 11 whether I would have been near the World Trade Center, and if I had, what would I be doing there. And then, of course, I wonder would I have made it out alive? Would I have jumped? I shudder and think of descriptions of the observation deck on the 107th floor, a quarter mile into the air. I would never be so foolish as to climb so high.

Howell Raines writes in his foreword to the New York Times’ Portraits: 9/11/01: The Collected “Portraits of Grief,” “But ‘Portraits of Grief’ reminds us of the democracy of death, an event that lies in the future of every person on the planet.” He continues, “When I read them, I am filled with an awareness of the subtle nobility of everyday existence, of the ordered beauty of quotidian life for millions of Americans, of the unforced dedication with which our fellow citizens go about their duties as parents, life partners, employers or employees, as planters of community gardens, coaches of the young, joyful explorers of this great land and the world beyond its shores.” I think being remembered for the ordered beauty of my quotidian life would be the worst way to be remembered. Each of the nearly 3,000 lives boiled down to 200 words and a corny headline. “I’ll Always Come Home.” Stopping To Chat. Of Cats and Cashmere. Kenny and Patty, Always. Life Is Like a Good Burger. Tenderized by Love. Ugly Cars, Beautiful Dream.

Still, I can’t think of a better way to remember.

JULIA HANNAH BOSSON

Julia was a picky eater as a child but voracious in all other ways. That’s not right, none of it is. Julia was never without her notebook. Please don’t define me by a negation. On Sept. 11, 2001, Julia was starting her second week of 7th grade. “She had just bought a new backpack,” her mother remembers. “It was lime green.”

In the weeks following Sept. 11, I was introduced to the nuclear bomb and the structure of the universe. The first step was to realize that the nuclear bomb did exist and the second was to understand that there were people who could use it. Soon after, my science class began to study the structure of the solar system. Each class made me sick, and I didn’t like feeling so stuck in my head. I dreamt of going blind. I made a promise to myself that I would never move to New York, where the buildings made it hard to breathe.

***

The exhibition manager of the September 11 Museum had recently gone on vacation to visit family in the Midwest. My desk was near his. He was a neat and competent man who kept a bowl of peanut M&Ms next to a Victorian lamp in his cubicle. Another member of the exhibition team came over to ask him how it was.

“It was good,” he said. “But vacation always ends too soon.”

“And how was the flight?”

“Oh, you know, how it always is. I get on the plane, and from take off to landing I don’t breathe or let go of the armrest. Like I’m physically holding the plane in the air.”

He laughed, they both laughed, the woman in the cubicle behind him laughed. I laughed. It’s fine.

Soon into my work at the museum, I discovered that the museum maintained some ideological disagreements with the Columbia Center for Oral History. At the museum, the oral historian for exhibitions, my supervisor, told me on the first day that she wanted to know how Columbia did their interviews. She told me that she hadn’t found Columbia very helpful in the museum’s research. At Columbia, Mary Clark rolled her eyes when I told her about the work I did at the museum. She asked me to verify rumors she had heard that, fairly, outraged her academic sensibilities—that the interviewers often asked direct questions about Sept. 11 instead of letting the narrative flow naturally, that they dissected the oral histories like journalists, looking for the punchiest quotations instead of a more truthful account; that the museum, out of its 400 interviews, had one or two with Muslims and none from other minority communities. Mary Marshall then sighed and complained about the state of “Curatorial Oral History,” as she called it. When I spoke to her, we were in solidarity, we were academics, we understood the ambiguity of memory.

But when I was at the September 11 Museum, I commiserated with my supervisor about people’s verbal tics, I complained about how the delivery doesn’t change the heart of what is being said, I listened to an interview, and I told them, “This has high Exhibition Potential.”

Clark told me that when she and her partners considered titles for their Sept. 11 project, she insisted that it be called “The September 11, 2001 Oral History Narrative and Memory Project” and ensured that in their initial proposal they never used shorthand in reference to the day. “ ‘9/11’ distracts us from the fact that it was merely a day in history, not the beginning and end of the world,” she told me.

In contrast, the National September 11 Memorial and Museum’s logo is “9/11,” the two 1s of the 11 in blue to represent the Twin Towers. With every internal memo, pointless email, press release, another incantation: 9/11.

***

I heard Sept. 11 through the voice of firefighters, widows, and teenagers. I heard it from bankers who almost fell through a window as they watched the plane hit their tower. I heard it from burn victims, from rescue workers, from architects. I heard it from artists. I heard it from New Yorkers who resented the tourists that came to gawk at the hole in the ground.

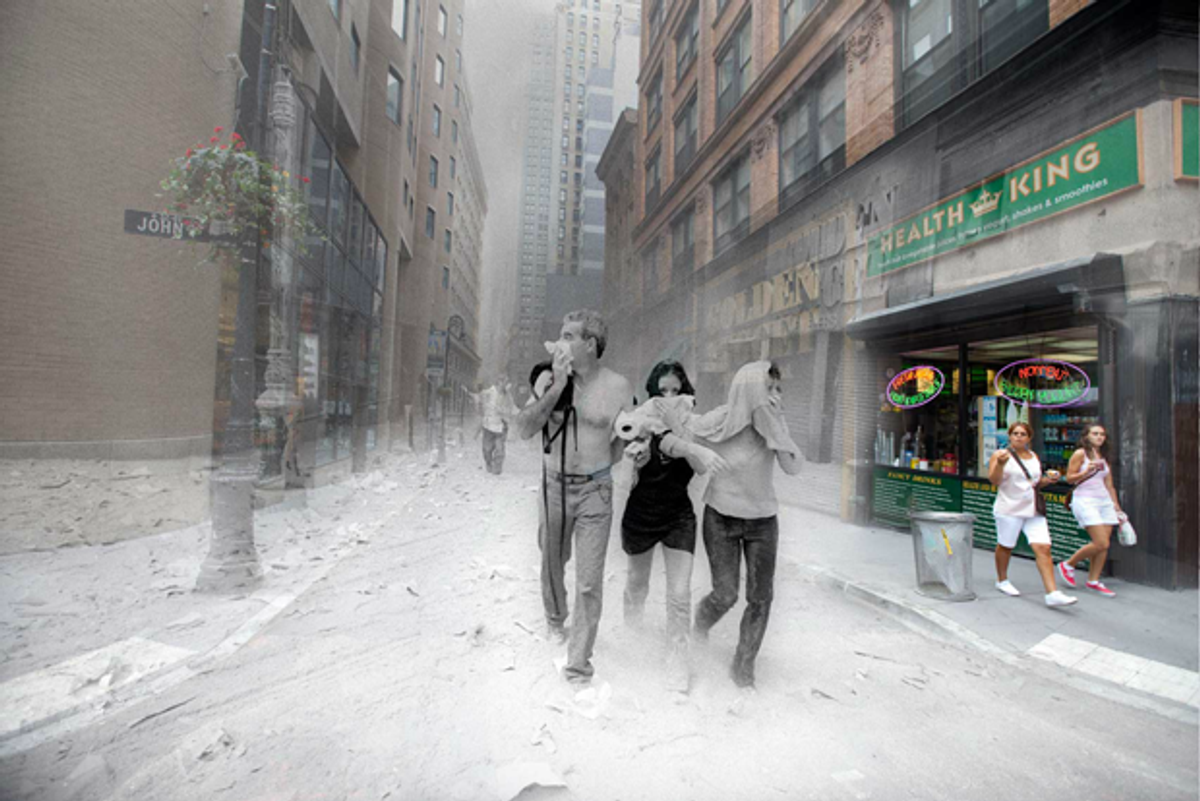

There is the plot that we remember. People who returned from the Trade Center with only blisters and a headache piece together the story after the fact, when they have heard others’ accounts, watched the film footage, spoken to their coworkers. Under the weight of history, all memory becomes holy. A man saves the undershirt he wore in a Ziploc bag and sends it to the museum nine years later. A woman’s burnt driver’s license is recovered and now is sacred.

Charlotte Delbo writes in Days and Memory: “Because when I talk to you about Auschwitz, it is not from deep memory my words issue. They come from external memory, if I may put it that way, from intellectual memory, the memory connected with thinking processes. Deep memory preserves sensations, physical imprints. It is the memory of the senses. For it isn’t words that are swollen with emotional charge.”

From the oral histories, I have gathered a vast collection of external memory. I have walked barefoot on New York City sidewalks with bleeding ankles because I am stubborn and don’t know how to wear high heels. I can describe the freight train pancake of the towers collapsing, as one floor slams against the other. But this is not the sound of the building’s fall, or the fear that comes with not knowing. The deep memories are the memories I can’t summon. These are the memories I can’t puncture.

At the museum, we joked that we were hot for men in uniform, but I wonder what any of us would say if we started talking to a fireman in a bar. In my mind he would be in uniform, the 75 pounds of equipment on his back that the others took up stairs into and into burning towers. We would have to talk about the 343 fire fighters who died on Sept. 11, and it would be strange because I would know more about their lives than I would about my own date.

After work on Thursdays, I went out with the museum’s three other exhibition interns for drinks at the Ulysses Pub on Pearl Street. We tried to get there early to beat the bankers to a table. The tall men and women quickly filled in the seats around us, smoking cigars, ordering sliders, talking, yelling, laughing, hundreds of Blackberries blinking and buzzing.

The four of us would sit, and often our conversations were quiet and mundane. We spread office gossip with indifference, lightly hinting our evening plans to one another without ever suggesting that we combine them. At a certain point in the evening, maybe as two of us finished our first beer, someone would mention something they had been working on that day. One of the exhibition development interns who had been working on the design of an age-appropriate walking tour through the museum leaned forward and described some of the archival CNN footage she had been sorting through.

We all leaned in, hunched over our picnic table and blond ales. I paraphrased Louisa Griffith Jones’ description of the jumpers. The media intern described the newscasters’ faces, the screams of the men and the women holding the cameras. We argued over the number of people who jumped—I remember the figure being somewhere around 200—and we tried to guess what the space the museum has dedicated to the jumpers will ultimately look like.

At other tables, well-groomed women flirted with tall men with nice watches on their wrists. I thought about how strange the four of us must look. The museum’s dress code was business casual, and most of us wore draping cardigans, wrinkled skirts, colorful blouses. Our hair was frizzy from the summer heat, and I knew my makeup must have been dripping. We were not as thin as the Wall Street girls, I thought, and I noticed that all four of us could work on our posture.

Many firms on Wall Street sent their interns to the Tribute Center, the memorial created by family members as an independent museum to depict the events and remember the losses of Sept. 11. They walked through in business attire, silk blouses and pressed blazers, shoes with heels. They were sent there to remember the men and women at Euro Brokers, Marsh and McLennan, and Aon who lost their lives at the same positions that these interns hope to fill. One day, when the museum opens, they will be sent down into the footprint of the towers, and they will see the exhibits and hear the voices that I have heard and edited into sound bytes. I will have helped them remember

***

The bulk of Columbia’s criticism of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum’s use of oral history comes from the tactics used by the interviewers. Liza Zapol, an Oral History master’s student at Columbia, delivered her paper “The Museum as Ventriloquist: The Use of Oral History at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum” at a conference on memory held at the New School in March of 2011. She quotes a conversation she had with my supervisor at the museum on her curatorial process:

“ ‘In an interview,’ she [my supervisor] says, ‘I am thinking of what this person is saying, and what they need to say, and I know what we want and what we need. And then there are specific curatorial concerns, like I know one section we are going to create is a listening space about the paper,’ she gestures as if her fingers were little bits of paper, ‘the paper flying everywhere. So someone will have shared their story and they might not have mentioned it, and I’ll say, can you tell me about the paper? And they’ll have to go back and tell me about the paper.’ ”

When I imagine my supervisor saying this, I imagine her laughing. I don’t imagine her thinking critically about her words, and I think if she could go back she would probably change her statement. But it’s true, the museum doesn’t devote a lot of attention to the authenticity of individual stories but rather looks for moments to give color to the narrative the museum has established in its exhibits. When my supervisor suggests that there was paper flying from the windows, she creates an image in the witness’ mind that has the potential to distract and influence a flow of testimony.

I have listened to these descriptions, and I have also seen the videos. I know that there were bursts of Xerox paper that ballooned out of the buildings on the planes’ impact. The papers fell, floating gently to land on the streets of lower Manhattan and farther. But had I been there, maybe I would have seen something else. Maybe a flock of white pigeons escaping from a cage. Or a cloud that had broken loose from the sky.

***

There have been countless studies in the field of trauma theory that document the therapeutic effects of oral history for the witness. But as it happens, when the Columbia Center for Oral History was in the process of gathering its own collection of interviews for its September 11, 2001 Oral History Project, Mary Marshall Clark noticed that the regular meetings she held with the interviewers were turning into something like group therapy sessions. She called in a professional psychologist to meet with the men and the women who were conducting the oral histories. She writes, “Some of the interviewers were unable to sleep, took on the physical symptoms of those they interviewed, or showed other signs of acute distress.” These people were sick with listening.

There has been a phenomenon that I have noticed at both the September 11 Museum and at the Columbia Center of Oral History in which people become defensive of their Sept. 11 story. They want to defend its legitimacy, they want to prove to themselves (and to posterity) that this event was significant, that it did change things for them, that they too were victims of trauma. “People feel pressured to have a connection,” Mary Marshall Clark explains.

“Honestly, outside of this project, Sept. 11 didn’t make that much of a difference on my life,” Clark told me. “I was lucky, I didn’t lose anybody. I think a lot of people, if they were honest, would say the same thing.”

Here are some things that have changed since I began work at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum: I pay more attention to numbers. I know some iron-welding terms that come in handy for crossword puzzles. I go on long walks and watch for firehouses to see the chart of the 343. I pause when the clock reads 8:46. On the subway I look at people’s shoes, and I think that everyone went through the trouble of picking them out and putting them on in the morning. And then I think of shoes that have no owner. I talk to myself in public. I stare at airplanes that glide above the city and I wonder if their flight path is normal. I think of so many lives a thousand feet in the air and I think that things are better here on the ground. I have a Xanax prescription and I take a pill when I reach security and two pills before take off. I got rid of my Facebook page because I couldn’t stand the interconnectedness. Before, I walked staring straight ahead. Now I often find myself looking up, like a tourist, to sense the height of the buildings and to observe the smallness of the sky.

Julia Bosson is a writer living in Brooklyn. She worked at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum from 2010 to 2011.