A Conversation With Gillian Laub

The photographer talks about ‘Southern Rites,’ her HBO documentary and companion book project about racial tensions in small-town Georgia

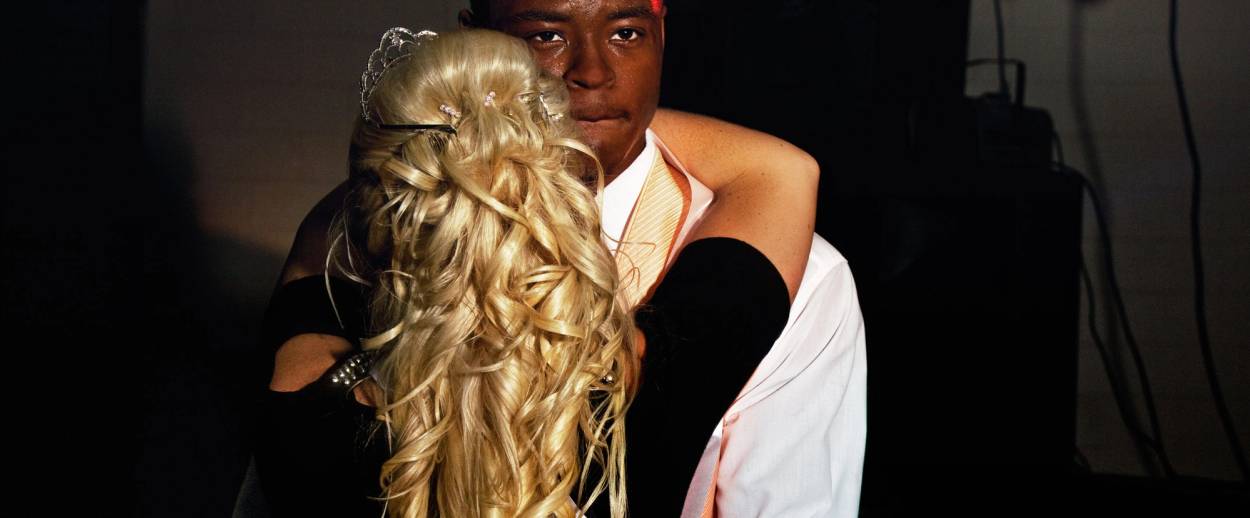

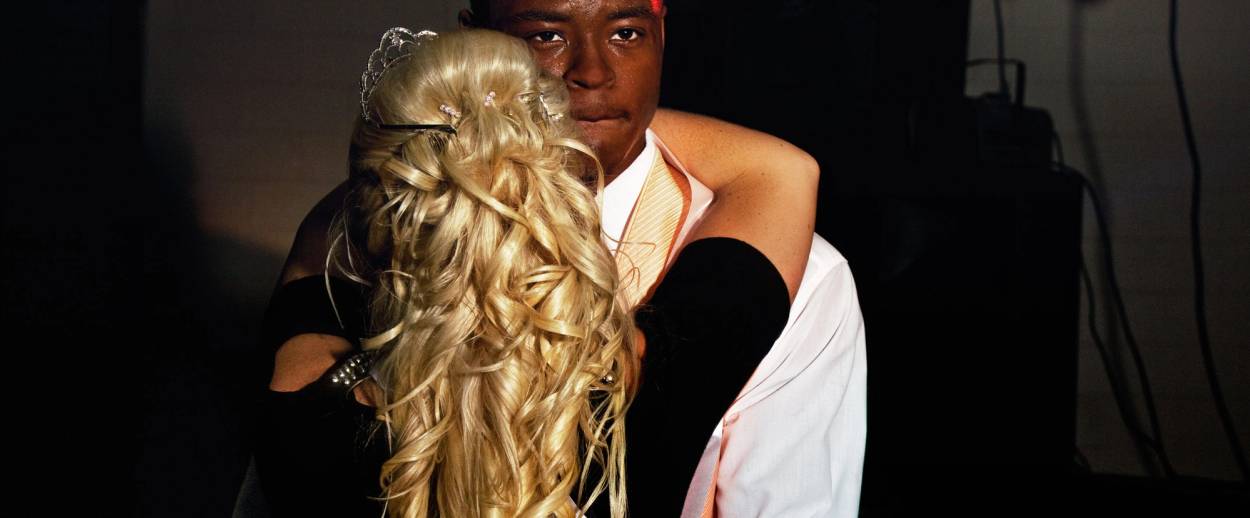

For her HBO documentary Southern Rites, photographer Gillian Laub spent 12 years getting to know the community of Mount Vernon, Georgia, home of one of the last segregated proms in America. Laub was first sent to photograph the town’s segregated homecoming parade for Spin magazine, which had received a letter from a disgruntled high-school student begging the media to pay some attention. Many in town were not thrilled to have a photographer on the scene. The homecoming eventually integrated, but the prom remained stubbornly segregated. The situation so haunted Laub that she returned many times on her own over the following decade-plus. What unfolded thereafter—including the killing of a young, unarmed black man by a much older white man, and a campaign for sheriff that left a beloved black candidate mysteriously not victorious—came as a shock to Laub. Produced by John Legend, the documentary premiered in May. Jon Stewart called it “affecting,” and the New York Times said it was “riveting.” Now Laub has published a book with the same title, which, in addition to showcasing her nuanced photographs, uses artifacts, letters, transcripts, and narrative to further illuminate the story of a community rife with injustice, complicity, and occasionally some hope as well.

What’s evident in her photographs of the prom and the families she befriended in town is Laub’s particular genius for personal connection. She’s photographed everyone from the Obamas to Ariel Sharon, Beyoncé to Dolly Parton, but in front of Laub’s camera people are always just that: people. In her photos, subjects appear remarkably unguarded. Her previous work, including Testimony, a series about Israelis and Palestinians affected by the Second Intifada, portraits of radical right-wing young female West Bank settlers (for Tablet magazine), a series on the beach in Tel Aviv, and an ongoing series featuring her colorful and storied family, has established her as one of our most insightful, witty, and deeply humane visual artists.

I sat down with Laub to talk about her work, the legacy of Jewish civil rights activism, tikkun olam, Jewish identity, and the impulse to always dig deeper.

What was your first visit to Georgia like?

I only went for two days. If it hadn’t been on assignment I would have stayed much longer, because I was so taken with this town. In some ways it wasn’t dissimilar to the town I grew up in. Homecoming, prom, Main Street: Here was this adorable village surrounded by Vidalia onion fields. I grew up eating Vidalia onions. Homecoming parade was full of cheering teenagers. It just felt really familiar, somehow.

But there were two girls on the float, one black nominee and one white nominee, and that was surreal. On the students’ ballot there was actually a column to vote for the white queen and a column for the black queen. This is something that I thought was way in the past. I was a naïve Northeastern girl; I had no idea this was still happening in our own country. I wanted to understand it more. There didn’t seem to be any shame! There was this sense that it was normal. There was pride in it. The girls were waving and smiling, with no sense that there was anything wrong.

Two days wasn’t enough time. I knew I needed to return to understand more.

What made you so certain? Why not shrug and say “OK, it’s creepy, but it’s not my town and not my problem”?

That photograph of the girls lined up by class and race. It stayed with me. I couldn’t shake it. Segregation was something that was celebrated in their town. What drives me toward a project is this gnawing feeling: I need to know more, I need to understand more. After that initial assignment, I had plans to go to Israel and do some work there. I had no idea what that work would be, but I knew I needed to go. The Second Intifada was starting up, and there was so much violence, so much upheaval. I had just bought a plane ticket, and I wound up working on Testimony for the next five years. But I was keeping in touch with my friends in Georgia, and I was keeping up with the backlash.

Tell me about the backlash.

The original piece in Spin caused some outrage in town, I heard, but it was early in the Internet, so it was all just word of mouth. So, a couple years later I just called up the school. This was 2008. Obama was about to be our president. I thought there’s no way prom is still segregated. I wanted to revisit the community regardless, but I was assuming prom would be integrated by now, even if only because the town would have been embarrassed by the backlash from the Spin piece.

I said, “I was wondering when your prom is?” and the school administrator said “Which one?” My jaw dropped. “The white folks’ prom is this weekend; the black folks’ prom is next weekend.” So, I called the New York Times Magazine and said listen, I have to go and photograph this. They were incredibly supportive. They said get on a plane.

Who were your contacts in Georgia? How were you received into the community?

My original contacts, high-school students, had moved out by then, they had graduated and moved on, so I was like this weird stalker, hanging around the school parking lot asking questions. The kids were all pretty welcoming, but some of the parents lost their minds, like “Go back to where you came from! Mind your own business!”

At one point I was hanging out with some of the students at a local restaurant and the cops came over to me. They said, “Listen, we’re just warning you that you should go back to where you came from. People around here like to take the law into their own hands, and we won’t be able to protect you if they do.”

My tires got slashed. I triple-locked my motel room that night and got out of there the next day.

Are you the kind of person who just digs your heels in when you’re threatened?

Not usually! I was scared to go back, but I had promised this one particular girl, Keyke, that I’d come back and photograph her and her friends at the black prom. I expressed some trepidation, but she was like, “Oh don’t worry, this is the black folks’ prom, no one will bother you! And my daddy is a cop, he’ll protect you!” And it was awesome. It was so much fun. The kids had a great time. I was totally welcome.

So, it was the white folks who didn’t want you around.

Yeah. All of the teachers go to the white prom. The black kids have to raise the money for their prom, so starting in the fall there are bake sales, car washes, whatever it takes to raise the money. And every year someone tries to integrate the proms, and it never works out.

So, of course I had to go back again the next year. This time without a camera. Just to try to talk to people, to explain that I really want to understand. I talked to the white parents, who were the ones in favor of keeping things segregated. I was like, “Please, talk to me, help me understand, I really want to understand.” And they began to talk to me. A camera can be intimidating. When I was just a person, it was less scary to talk to me. A stranger with a camera is scary. So, I started doing audio interviews with people. I said OK, yes, I am a Yankee. Where I come from, people are shocked that there are segregated proms.

How did you present yourself? How did they identify or contextualize you?

They didn’t know what exactly to make of me. Where did I fit in to all of this? Some people thought I was Mexican, some people thought I was Italian, they couldn’t quite figure out where I fit in. I told them I was Jewish. They didn’t really know what that meant. A couple of people friended me on Facebook, where there were photos from my wedding, and they were like: “What’s that thing on your husband’s head?” I said, “It’s a yarmulke, he’s Jewish.” And they were like, “Oh, yeah. I met some of those before.”

Incidentally, there is a significant Mexican population in town, a lot of whom are farm workers. The Mexican kids can go to the white or black prom. They were hardest for me to access or interview. They were too scared to talk to me. I think a lot of their families weren’t legal, so they didn’t want to jeopardize their families.

So, at this point you’ve become a somewhat accepted presence in town, and your tires aren’t getting slashed, and you’re collecting audio interviews, and people are familiar with you. How did the film evolve from there?

The Times published it as a photo essay and multimedia piece, with audio over the slideshow, and hearing the voices felt so powerful. I didn’t have the tools then to make a film, but I was motivated at that point to start recording. I took a class and learned how to shoot film the way I made photographs. It took a lot of practice. The early footage was not very good. Some of it wound up not being usable, which was devastating. But it got better. I love being able to use new mediums to tell stories. I came to film out of necessity in order to communicate this narrative, in all of its complexity. Photography will always be my first medium, but I feel like I’ve really expanded my repertoire.

I don’t want to give anything away, but the segregated prom is only the beginning of this story. What unfolded over the years in front of your camera is pretty shocking.

Half the book and more than half the movie is about a killing. Keyke’s high-school boyfriend winds up being shot and killed by an older white guy in town. And then of course Keyke’s father is this well-respected black cop, running for sheriff with tons of support, but he mysteriously loses, under very suspicious circumstances.

The prom is what initially brought me to Mount Vernon, and the prom is what’s gotten all the media coverage, but what developed in the story, what I saw unfold, is more serious than a school dance. The prom seems insignificant compared to a death. The prom is the context in which the murder happened, though. And it’s happened over and over again in this country. A young, unarmed black man was killed by an older white man who felt threatened and felt he had the right. No newspaper reported the killing until a year later.

I’m curious about what you said about the parallels between Vidalia and the town you grew up in. Why do you think you felt that sense of familiarity? What do you think underlies your obsession with this town and its problems?

Growing up I was the “ethnic girl.” My town was affluent and very white. There were other Jews but they all had Christmas trees. I always wondered: What does being Jewish really mean? I begged my parents to let me go to Israel on a teen tour, and they let me go. I was the first in my family to go there. When I came back from Israel, my boyfriend picked me up to go to a movie at the mall. I was wearing a Star of David necklace, and he said, “Tuck that shit into your shirt.”

Most American Jews these days identify as white, but that’s not quite accurate, is it?

I am not one to speak for all American Jews, but my identity is wrapped up in wanting to treat people with respect and dignity. Before I went to Mount Vernon, I had never experienced a place where there was such overt and covert oppression, accepted and reinforced by the structures of the community.

Put that way, it isn’t so dissimilar to the work you’ve done in Israel.

The only thing I have the power to do is tell the story. It’s about digging deeper. Which is what I’m trying to do when I photograph my family, or any family. I love photographing families. This community was a kind of dysfunctional family, like every community is. We’re all victims of history, victims of the system, victims of our own loyalty to whatever twisted legacy.

When you’re there, entrenched with people, you start to understand how these things can happen. It’s hard to change. It’s hard to let go of what you know. These cultural narratives are playing out, and it’s important to understand them, but they’re not always so nuanced. So, my aspiration is to unpack all the complexity, to understand people as people. That’s where the nuance is.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elisa Albert is the author of the novelsAfter Birth, The Book of Dahlia, and the story collection How This Night is Different.

Elisa Albert is the author of three novels and a story collection. From 1969 to 1980, her stepfather was an active member of Kibbutz Be’eri, where Hamas carried out mass civilian slaughter on Oct. 7.