Woody Allen’s Biographer Tells All

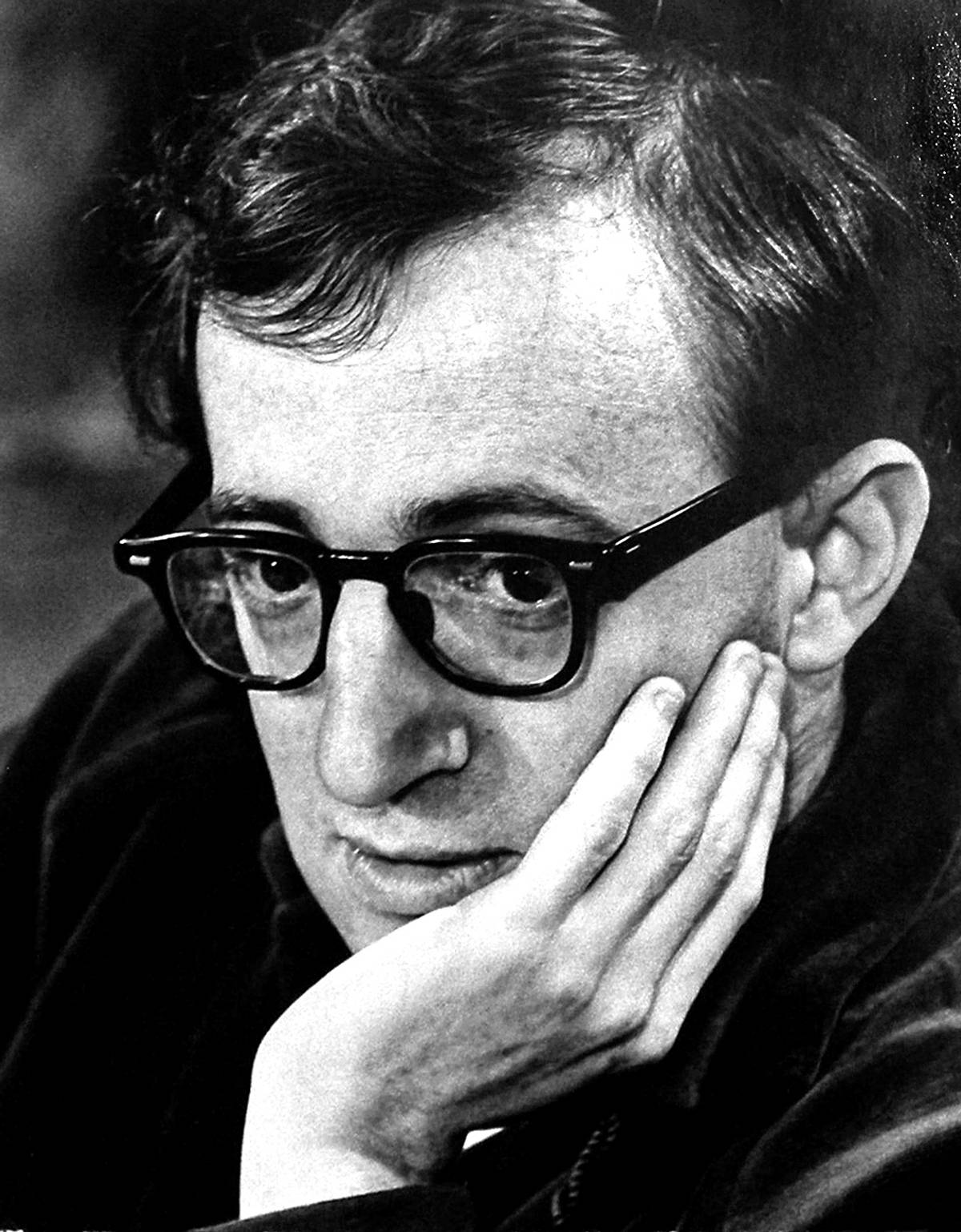

Id meet ego. Ego, id. The celebrated, controversial, highly self-aware filmmaker’s new ‘Café Society’ is about himself—but who is that?

After completing my biography of Woody Allen, I had a dream that I presented him with a copy of my book and said to him, “You will be very happy with this.” In another dream, he was sleeping and I put my face alongside his. I awoke with a feeling of peacefulness.

These dreams will surely support the feeling among some critics that I fell in love with Woody Allen. Actually there is love and admiration in the book, but plenty of criticism as well. I thought that he was cruel to Mia Farrow when he left nude pictures of Soon-Yi for her to see; that he had a deep-seated ambivalence toward women because of a mother who hit him every day when he was a child; that a good number of his films are terrible—and that almost every good or terrific film is followed by one or two or three lousy ones. For truly wretched, check out Interiors, September, Another Woman, Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Whatever Works, Hollywood Ending, Irrational Man, and Shadows and Fog.

Now that I think of it, he has written and directed some of the most awful films that any major film director has ever created, and far more terrific films than any other film director.

His films can be rapturous and joyful—like the New Orleans jazz scores that underscore them. And of course he speaks for all the shnooks in the world, Jewish and gentile, male and female.

One of the most scrutinized, reported and gossiped-about celebrities in American show business history, Woody himself remains unknown. If Woody has read my book, I doubt he is entirely pleased with it. After all, the adoring 1991 authorized biography by Eric Lax that told us that Woody had never done a bad thing brought the response from Woody that while it was favorable, he thought it was not favorable enough.

When I rang Woody’s doorbell and left a letter for him he responded the next day with a characteristic ambivalence: He didn’t care what I wrote, but could he trust me? If I was favorable about his work, it might be because I lacked good critical judgment. I am not sure he understood, although I told him that the last thing I wanted was to undertake an authorized biography in which the subject was entitled to peer over the shoulder of the author. He wrote me:

Here is the problem and please don’t in any way take this personally. While I have great respect for authors and journalists in general I have had too many experiences with ones I never should have trusted and there is no way for me to feel any security about your project. You can understand that I have nothing but your description of your intentions and while they may be 100% honorable there is no way I can verify that. I have no doubts about your qualifications and your résumé but beyond that there is no guarantee that yet another book about me would serve any constructive purpose. All the facts about my life have been written about and rewritten about and my work has been dissected in books and articles all over the world for years.

He went on to question the relevance or mental acuity of some of the people I had already interviewed, and while he conceded that critics like Richard Schickel and Annette Insdorf “have been very supportive,” John Simon, on the other hand, “has never liked my work at all.” (This turned out not to be true, which I discovered when I interviewed Simon.)

“In addition to this,” Woody wrote,

your project was undertaken without ever asking if it is something that I wanted done so you can imagine that would make anyone quite suspicious. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting anything wrong here, only explaining to you why one might feel reluctant to participate…. I don’t mean in any way to be difficult or obstructionist but decades of experience have [made] me very wary. I might also add your notion that Crimes and Misdemeanors and Zelig are my two masterpieces when neither is a masterpiece or are either even the best films I have done worries me. It makes me wonder if I would consider, even if flattering, your takes on my films to be just more wrong-headed appraisals and would not add anything to the cultural landscape. If I am wrong about all of the above tell me what am I missing?

I tried to tell him what he was missing but I doubt I was convincing. Nevertheless, he was anything but obstructionist. Two years later, I count 22 emails from him, some very short but almost always helpful and reasonable, and then, at the last, an 80-minute personal interview with him that he’d insisted he would never give me because of a commitment to his authorized biographer. I was so sure he would not agree that I suggested a 15-minute meeting, which he changed to an hour, and then extended for another 20 minutes.

So—this man who is a picture of ambivalence was nevertheless a mensch who gave a human, individual response to someone who was a total stranger to him and who could easily have contributed to his feelings of unease in the world.

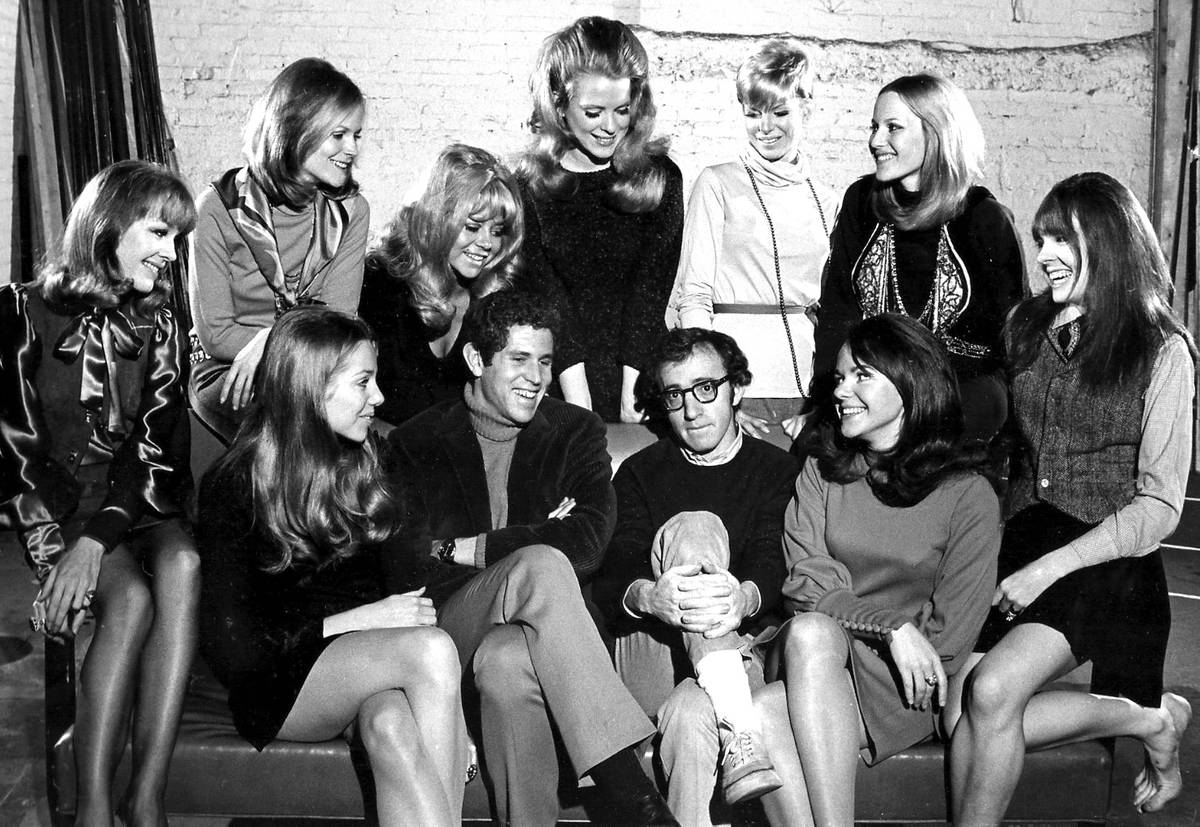

A long time back, in 1968, Woody offered advice that was really a statement of principle and a foreshadowing of the paths he would take for the next half century and more. He envisioned “the chap who really will discipline himself and develop. I mean really hard work. Writing material for yourself, not believing your press notices whether they are good or bad, constantly doing new things, constantly moving into new areas—movies, Broadway….”

When asked if this meant taking risks and not caring about failing, Allen replied: “Right! Once you start to think about, do the newspapers like me? or did the audience like me? or am I making enough money?, or should I be doing this? The only important thoughts are: Am I being as funny as possible in as many different ways? Once you view the rewards too tantalizingly, you’re dead. Then you start accepting and turning down jobs on the basis of how it affects your income tax. Then you might as well be working in Macy’s, except that the money is better in this business.”

Remember the bearded, paunchy Sheldon Flender (Rob Reiner), the king of the bohemian Jewish artists who sit around eating and kvetching in Bullets Over Broadway? Sheldon is so proud of the fact that his work has never been published; it’s a sign of how brilliant he is, that he will never sell out. “I knew this when I was in my late teens,” Woody has said. “That there were always going to be distractions. And I felt that anything that distracted from the work and minimized your effort on it was a self-deception that was going to be detrimental. So to avoid getting caught up with a lot of writing rituals and time-wasting, you’ve got to get there and just work. Art in general and show business is full to the brim of people who talk, talk, talk. And when you hear them talk, theoretically they’re brilliant and they’re right and this and that, but in the end it’s just a question of who can sit down and do it? That’s what counts. And the rest doesn’t mean a thing.”

He arrived at the right moment when every preconception about American life came into question. First there was Jules Feiffer with his Village Voice cartoons of Jewish bohemians and neurotics. Then the brilliant, innovative comics on Macdougal Street in the Village at Cafe Wha, the Bitter End, the Gaslight: Nichols and May, Shelley Berman, Lennie Bruce and Mort Sahl, Woody’s idol. By 1967 Jewish actors were no longer in the closet as Jews or playing Italians or Native Americans. Films with Jewish content and Jewish stars had emerged, with Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate, Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker; Lumet’s comedy Bye Bye Braverman starring a new Jewish leading man, George Segal; Mel Brooks’ The Producers, and many more, culminating with Barbra Streisand in 1973 in The Way We Were. It was a Jewish New Wave, as J. Hoberman put it. Woody Allen was a leading man, and he was not a Groucho Marx vaudevillian Jew, or even a Mel Brooks-type Jew. He was defiantly Jewish, a real person, a film star, a New Yorker. And he looked like a normal person—OK, maybe a little worse, but normal. He was mainstream and he was subversive—he tore everything that had been revered apart. And he was the outsider—psychologically, not economically, like Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp.

Today, as from the start, he has total artistic control of his work. “Money in any way has never been an issue with me,” he wrote me. He has never taken the big, controlling money that would kill him as an artist. He was never tempted to sell out or to try to outdo himself, and he didn’t care to ingratiate himself with the mainstream. He avoided the money that would mean he had to make blockbuster movies with huge box office results, the money that would make him a creature of the Hollywood culture he detests, the money that would make him dependent on the critics for validation. His sense of self-worth doesn’t come from money; it comes only from his work.

So we are talking about enormous inner strength and self-belief, and it doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense in someone who plays the ultimate schlemiel, fearful of bugs, elevators and germs, who seemed to be afraid of his own shadow. Yet he is all of these things. John Lahr said of Chaplin and Woody Allen: “Both are comic geniuses who give life without actually loving it.” And in truth, Allen seems like a pretty somber, staid guy, but he is not unknowable. His daily pattern is predictable. He’s quite reserved and proper in his speech; boldness is reserved for his writing. He once had a lightning speed; now he has reached the melancholy stance of later age. That melancholic strain is especially noticeable in his public interviews; it was not present in my meeting with him.

He knocks off at 6 no matter the urgency of the situation on the movie set, goes out for dinner and wine, or to a basketball or boxing match at the Garden. He sometimes watches Charlie Rose. I once suggested (and I’m sure I was one in a long line) that perhaps he should spend two years on a film and maybe not knock off so easily. He didn’t respond to this at all. A friend told me that he was incapable of that kind of rigor. (I think what he does is equally “rigorous.”) It’s “the empire of the instant.” “His relationship to time is bum-bum-bum. It’s based on sensory pleasure, like window-shopping. It’s always about the sensory experience of the moment. And natural anxiety, which he has. He needs that immediate gratification. That’s why he’s not that into literature. How could he be? It takes time. Unless it becomes a passion, which it isn’t for him. Notice in the early films how many names he drops. He wants to show everybody how smart he is. He’s not a scholar and he’s not a great mind. But he’s got this comic talent and some musical talent as well. So in a sense he’s an ordinary guy with a pocket of talent.”

The fears and phobias that Woody has invested in his characters are not far from his life experience. The film producer Vincent Giordano recalled for me that he was in an elevator with Allen in the 1980s: “Every time I got on the elevator, he would turn and face the back wall. I felt badly for him because it looked like he was scared or something. And he would wait for you to leave the elevator before he would leave. One day I decided I was going to wait for him to leave first, and I held the door open for him. He panicked, waited, then turned and bolted out the door.”

Another friend commented, “There’s never a feeling of guilt with Woody; it’s always you who are at fault and it’s your responsibility. He never feels he has any complicity in the situation. He is the guiltless. So you always have to live up to the standard that he sets for people to abide by, according to what he deems to be the ideal. And there’s a secret haughtiness; that he’s superior to others. He riled his mother up constantly. He would certainly seek to provoke her. But he was very good to his mother and father. Look, like most people in the world, he has admirable qualities and some features that are not so pleasant.”

So we are not talking about a pussycat. “There’s something self-loathing about Woody,” screenwriter Gary Terracino, who seems to live with Woody in his head, told me.

But it’s not quite self-destructive because he’s always done things the same way. There’s something contemptuous, there’s a need to upend things without upending things, but to shake things up, to let people know he can walk away. So he walked away from Mia even with the kids. He squashed her like a bug without barely noticing it. Before that he walked away from being a red hot TV writer. He was really popular on the talk-show circuit. He ditched that. Then he wanted to be a writer/director/producer. He walked away from success after success. At the time he was with Mia, he’d become this cuddly warm and fuzzy bear. At that point he was a titan of the indie scene and of what mainstream Hollywood filmmaking could achieve. And he blew that up. When a nearly 60-year-old man runs off with his 19-year-old stepdaughter—this is a guy who’s self-aware, who’s been in analysis his whole life and insists that his young children be in analysis—he’s well aware that this is a big fuck-you to people. He was a little too warm and fuzzy and cuddly for too long for his taste. He was blowing up his life. But he knew he could put it back together again exactly as it was, that it would remain exactly the same. There’s some self-loathing and arrogance. The whole ‘I would never want to join a club that would have me as a member.’ He’s walked away from success in a way that no other major filmmaker has. They can’t. They won’t. Woody, more than any other film-making artist: Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola—they just self-immolated in the Hollywood system. Unlike so many of the others, he didn’t die with the ’70s. Coppola flamed out. Scorsese, by his own admission, spent the ’80s trying to make commercial movies that would hit. Spielberg was making these megamainstream hits. Bogdanovich went bankrupt. Terence Malick dropped away. Coppola and Scorsese were bankrupt and Scorsese had the coke problem. Woody kept his budgets relatively low, and had these personal relationships with the Jewish moguls at United Artists, Arthur Krim and Eric Pleskow and David Picker and his agent, Sam Cohn, who was the most powerful theatrical agent in the ’60s and ’70s. They protected him. Woody has been very smart about the situations he’ll engage with. He has played with fame and celebrity in a brilliant way that I don’t think he gets enough credit for. He knows how to fan the flame without being a whore.

Since this is my fourth biography, comparisons with previous subjects I have written about are inevitable. Tony Bennett, about whom I wrote a very favorable but honest book that mentioned former mob ties and his explosive harangues against musicians who worked for him, was anything but friendly. In fact, the deafening silence I was treated to by Tony and the howling rage transmitted by his son Danny in The Daily News in a message from his secretary, Sylvia Weiner, was that angry part of him that Bennett has spent a lifetime trying to conceal. (“Tony B. has spent a lifetime being Mr. Sweetness,” I told the newspaper). For me, Bennett’s biographer, that aspect of his personality in no way mitigates his talent, his love of painting, his devotion to The Great American Songbook and his insistence on musical quality and on extending his artistic range. He actually has some of the same kinds of stamina, persistence, artistic dedication, longevity and inventiveness as Woody, but for candor I’d take Woody any day. “There’s an ogre behind that door,” my friend Lennie Triola, the concert producer, warned me about Tony from the outset, and I did not believe him. But I soon learned that there are two Tony Bennetts, and I don’t think that’s a rarity in the history of the human condition.

But inevitably the contrast between Bennett and Woody Allen, who is unceasingly honest with a relentless refusal to hide his depressive nature, put Allen in a more sympathetic light for me.

Allen’s feelings about the Holocaust as the most unconscionable fact of the 20th century also resonated with me. He wrote me: “Since the Holocaust was such an immense event in my lifetime it couldn’t help but wind up as a sporadic or even frequent issue in my work. … There are certain crimes that are simply unforgivable. I believe we are a species that could very easily die out with nobody to thank for it except for ourselves.”

He wrote in 2002 of his reaction to Elie Wiesel’s novel Night: “Wiesel made the point that the inmates of the camps didn’t think of revenge. I find it odd that I, who was a small boy during World War II, and who lived in America, unmindful of any of the horrors Nazi victims were undergoing, and who never missed a good meal with meat and a warm bed to sleep in at night, and whose memories of those years are only blissful and full of good times and good music—that I think of nothing but revenge.”

When I shared those words with Dorothy Rabinowitz, she commented: “Those are words I could have spoken. I had a childhood that was secure, happy—I was born in America, was oblivious to what was going on in Europe. I had the cookies and milk when I came home from school, a warm bed, a family—and I, too, think of nothing but revenge. Except I don’t think it’s odd to feel that way. Woody said what no one else in his position has dared to say.”

No comic star—or any star—has made such repeated references to the Holocaust in his work except Allen—not remotely. He is the most identifiable, brazen and forthright Jewish artist in the world. It almost strains credulity that a Jewish film star who placed his Jewishness front and center and audaciously proclaimed it, who expressed his preoccupation with anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, could capture the imagination and beguile a wide universal audience has Allen has done.

***

After I finished my biography, there were the inevitable friends, strangers and acquaintances coming out of the woodwork with additional stories about Allen that amplified and confirmed my portrait of him. (I am quoting several of them in this piece.) With little capacity for joy in life, as he says of Harry Block in Deconstructing Harry, writing saved his life. He has said that he has no idea what he would have done in life if he hadn’t been a comedian and writer. He suggested two possibilities if he hadn’t been an artist: He might have been a messenger boy (as his father was in later years for Woody’s manager, Jack Rollins) or a towel-room attendant. My friend Judy Liss told me this story about Woody after the book’s completion: She saw him at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village at the beginning when he started doing standup, when he would throw up before every performance, and he had bitten his nails off, and his body was trembling. She told me, “It was cringeworthy to even watch him. How could he survive? Why was he punishing himself this way? Why was he doing this to himself? You had the feeling there was nothing else he could do in life.” Yet it’s also true, I learned, that as Diane Keaton said of him, “Woody has balls of steel.”

Some questions I regret not asking him: What was his relationship to his observant grandparents? They had all fled the oppression and pogroms of shtetl life. His mother’s parents, Sarah and Leon Cherry, spoke Yiddish and German and ran a small luncheonette on the Lower East Side. Woody’s paternal grandparents, Sarah and Isaac Konigsberg, were on a higher economic plane than the Cherrys. A traveling salesman in Europe for a coffee company, Isaac dressed elegantly and had a box at the Metropolitan Opera. He owned a number of elegant movie theaters in Brooklyn, including the Midwood, around the corner from Woody’s home on East 14th Street, and a fleet of taxicabs. Isaac lost his fortune in the stock-market crash of 1929 and was reduced to working in the butter-and-egg market; Woody’s father worked with him. (Remember that in Radio Days, Joe, the young Woody, asks his parents what his father does for a living and among their vague responses, his mother says he’s a “ big butter-and-egg man.”)

A friend of mine criticized Allen by saying he’d never been to Israel and had never given a dime to Israel. Well, I may have given a dime to Israel in a pushke once, but no more, and I’m not crazy about the settlements, but I consider myself a big fan of the country—in fact, I don’t think one can cite any hope that came out of the sewer of the 20th century except Israel’s establishment and survival and the victory of the civil rights movement in the United States. In February 1988, Allen published a letter in The New York Times objecting to Israeli treatment of rioting Palestinians. He expressed his fury about the Holocaust in an article in Tikkun in 2002.

Allen told Yediot Ahronoth in 2012: “I support Israel and I’ve supported it since the day it was founded. Israel’s neighbors have treated it badly, cruelly, instead of embracing it and making it part of the Middle East family of nations. Over the years Israel has responded to these attacks in various ways, some of which I approved of and some less so. I understand that Israelis have been through hard times. I don’t expect Israel to react perfectly every time, and that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a wonderful, marvelous country. I’m just worried about the rise of fundamentalism in Israel, which I think damages its interests. I also have questions about their leadership, which doesn’t always act in Israel’s best interests. But even my criticism of Israel comes from a place of love, just like when I criticize the United States.” In 2013, referring to the double standard applied in the barrage of criticism of Israel, he told Israeli television that political criticism of Israel can conceal the deeper hatred of anti-Semitism. “I do feel there are many people that disguise their negative feelings toward Jews, disguise it as anti-Israel criticism, political criticism, when in fact what they really mean is that they don’t like Jews.”

However, he also told Marlow Stern of the Daily Beast in July 2014 of his feelings about the situation in Gaza, that it was “More terribleness. … It’s a terrible, tragic thing. … But I feel that the Arabs were not very nice in the beginning, and that was a big problem. The Jews had just come out of a terrible war where they were exterminated by the millions and persecuted all over Europe, and they were given this tiny, tiny piece of land in the desert. If the Arabs had just said, ‘Look, we know what you guys have been through, take this little piece of land and we’ll all be friends and help you,’ and the Jews came in peace, but they didn’t. They were not nice about it, and it led to problems, and over the years, both sides have made mistakes. There have been public relations mistakes, actual mistakes, and it’s been a terrible, terrible cycle of mismanagement and bad faith.”

Not very nice? Actually I think I left this quote out of my book because I found it distasteful, especially that childlike reversion to words like “not very nice.” Suddenly we are back in nursery school with little Woody at his wooden desk, an innocent except that he wants to shtup all the girls. Here he blathers on, keeping his head in the sand about all the rockets shot at Israel, wringing his hands and blaming both sides. The language, the evasion, the absurdity of this is undeniable. This is pragmatism and it is cowardice. He saw dead children and he didn’t want to be involved defending Israel. And more than that, it is that full-fledged ambivalence that is an essential part of Allen’s personality. It is cowardice behind the courage about Jewishness and the Holocaust; in effect, he is still hiding from the goyim. He is not alone, and I do not condemn him for it. How often did Sidney Lumet, Paul Mazursky, Mel Brooks, Lillian Hellman, Arthur Miller, Arthur Penn, Clifford Odets and countless other directors, playwrights, actors and screenwriters speak out for Israel? In the history of Hollywood, Ben Hecht was one odd and brave exception, obsessed as he was with the Holocaust. When have we heard from Judd Apatow?

Allen has the perspective of many entertainers who, as assertively Jewish as they are, still do not want to be pigeonholed as “too Jewish”—too narrowly focused on Jewish issues and Israel at a time when Israel is a very unstylish subject for an important, fashionable segment of the public, including the media. It will hurt the box office.

What Allen legitimately fears and detests is any form of fundamentalism, and he fears that for Israel. Like so many of his attitudes, that feeling may partly come from his experience of his punitive Orthodox mother who, he has stated, hit him every day when he was a boy. Allen could wander unimpeded in his wild thoughts with his father, who was a cheerful, easygoing fellow at Sammy’s Bowery Follies, always carried a gun, was a gofer for Albert Anastasia, and, allegedly, a member of a firing squad at one time. According to Allen, Marty Koenigsberg “never had a thought in his head,” but he was fun to be around and loved his mischievous gambler and magician of a son.

I have more than a strong feeling that Woody did not want me to portray him in my book as “too Jewish.” That attitude is not confined to today. It is an attitude that can be traced back to the early movie moguls, refugees from Nazi Germany, who banned Jewish-looking actors from their films, made them Italians (John Garfield, Paul Muni) or even Native Americans (Maurice Schwartz, the great Yiddish actor, was cast as Geronimo). Today it still can be seen as a protective gesture. I have met countless Jewish figures in the business who talk, act and sound Jewish but who prefer, for box-office or image reasons, to curb their enthusiasm in public about Jewish matters, particularly Israel. Woody has always insisted that he is a coward. In an excised scene from an early film, he is a ventriloquist being interrogated by the Gestapo. He asserts bravely that he will never give them information, but he holds up a puppet and says, “But he can.”

Chalk it up to Woody’s ambivalence about most things in his life, especially himself. It was the Jewish movie moguls, Jewish Hollywood, who took Woody to their hearts from the start. United Artists was the most prestigious independent movie studio in the United States in the ’70s. Arthur Krim was chairman of a company that included Eric Pleskow, Bob Benjamin, William Bernstein, and Mike Medavoy. These were cultured and literary Jews not governed by solely mercenary motives. An American entertainment lawyer, Krim was the former finance chairman for the Democratic Party and an adviser to presidents Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy on issues involving arms control, civil rights and the Middle East. He arranged the party in Madison Square Garden for JFK with Marilyn Monroe: “Happy Birthday, Mr. President.” Eric Pleskow, whom I met with in 2014 when he was 90 years old, fled the Nazis in 1938 and emigrated to the United States with his family. He served in the Army and after the war returned to Austria and conducted interrogations during de-Nazification. It was the perfect place for Woody. Arthur Krim would become one of his most supportive mentors.

“At the beginning,” Pleskow told me,

Woody had Jack Rollins and Charlie Joffe [in his corner]. He had David Picker. I think Woody perhaps had a complex because of his lack of size. There’s also a certain affectation about him, too. If you didn’t want to be recognized, which he claimed, then you didn’t wear a shtreimel [cap] like that walking down Madison Avenue.

Woody was a very talented man, basically a very modest human being, very nice to work with. Of course, I didn’t interfere with him. I very often felt like a Medici, his patron. When he told us that he wanted to entitle his film Anhedonia (incapacity to enjoy life)—it later became Manhattan—Arthur Krim walked to the window and said he wanted to jump out. We felt that all the great work done by Woody entitled him to do Interiors. We cherished the association with him. I let him make one of his films, September, twice. There’s nobody in the industry who would do that. We weren’t going to destroy our relationship with him over one film. When I saw it, I was numb. Arthur had a sickly look on his face. We never rejected anything he brought us. Not once. There is no other Woody Allen. If you want to be associated with a man like that, you can’t apply the ordinary standards. I say this modestly: I think he was fortunate to be working with us. We recognized who he was. I couldn’t have dealt with everybody else like that. I would have been out of business. I took chances with him. I’m glad we did; I have no regrets.

For Woody, time stands still. He’ll make many more movies. They’ll carry him in, but he’ll still make them. I think he was never behind getting more money for himself. I never heard it once. Not once. And his shyness. I understood from several co-workers that he didn’t feel comfortable coming into my office because of my job, my position. So I went down to meet him.

The route to the Jewish Woody is in full view in four later films: Broadway Danny Rose, Radio Days, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and the underrated Anything Else. In Broadway Danny Rose, the film that first made me really love Woody, Danny is the gentle, sacrificial Jewish saint who helps the underdogs of the world. With his “Chai” pin, his gaudy plaid jackets, his insistence on morality and the need for guilt, his kindness and gentleness, Danny Rose is Allen’s tribute to his Jewish manager, Jack Rollins, who gave life to Woody, who believed in him and stood by him, “never taking a commission,” Woody told me, during the years Allen was frightened to death about becoming a performer. It is Danny who quotes his Uncle Sidney (is there a more Jewish name than Uncle Sidney?). In Anything Else, you get a taste of Allen’s rage in the person of the paranoid teacher, David Dobel. Allen told Douglas McGrath in Interview magazine that the character of David Dobel has personal aspects of himself in it, and it is here that we grasp what Allen wrote in 2002 that regarding the Holocaust he “thought of nothing else but revenge.”

Dobel, a central character in the film portrayed by Allen, says (in words almost identical to those he expressed in a letter to me): “The crimes of the Nazis were so enormous it could be argued that it would be justified if the entire human race were to vanish as a penalty.” This is repeated twice in the film.

Dobel, a schoolteacher, is a mentor to Jerry Falk, a young writer in his 30s. Dobel constantly refers to the Holocaust and to anti-Semitism. Coming out of a comedy club with Falk, he tells Falk that a group of men looked at them and one said, “Jews start all wars.” He tells Falk, “We live in perilous times. You got to stay alert to these things. You don’t want to wind up as black-and-white newsreel footage scored by a cello in a minor key.” He urges Falk to purchase the gun and a survival kit. He has a gun in every room of his apartment. “The day will come when you need a weapon,” he says. “Why?,” asks Jerry. Dobel replies, “So they don’t put you in a boxcar.”

Jerry Falk: “Dobel, you’re a madman.”

David Dobel: “That’s what they said in Germany. There were actually groups called ‘Jews for Hitler.’ They were deluded. They thought he would actually be good for the country. … You are a member of one of the most persecuted minorities in history.”

Falk tells his girlfriend that Dobel “is still convinced that the slaughter of 6 million Jews is not enough to satisfy the anti-Semitic impulses of the majority of the world.” Dobel tells him: “What you don’t know will kill you. Like if they tell you you’re going to the showers. But they turn out not to be showers.”

“The issue is always fascism,” Dobel insists. He eventually shoots a state trooper who suggests that Auschwitz was just a theme park.

Crimes and Misdemeanors is, I think, Allen’s greatest film, the one in which he concludes that evil has triumphed over good without the slightest qualms in the people perpetrating it. Allen’s view of the world is encapsulated in this film, where darkness and comedy merge inextricably, but where darkness wins out. Inherent in the script is the death of all meaningful religious belief and the urgent need to replace that belief with a relative morality without any religious moorings, without any conviction that there is a moral center to life. Here, at last, Allen revisits his Orthodox Jewish past with respect and without satire, irony, or comedy. Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau) who will ultimately kill his mistress (she is threatening to destroy his marriage and career) and get away with it, recalls that his Orthodox father told him, “The eyes of God are on us always.”

The figure that haunts Crimes and Misdemeanors is Dr. Louis Levi, a character, Woody told me, who is a composite of Primo Levi, a Holocaust survivor, and Dr. Martin Bergmann. Dr. Bergmann had a notable career as an outstanding psychoanalyst whose primary work was with Holocaust survivors and their children. He had taught for many years in the postdoctoral program in psychoanalysis at New York University. His father, Hugo Bergmann, was a noted philosopher in Prague, a close friend of Kafka and Martin Buber, after whom Martin Bergmann was named. He emigrated to Palestine in 1920 because of anti-Semitism and became a professor at Hebrew University. After Israel was declared a state, he was elected the first rector of the university. It is Dr. Bergmann who portrays professor Levi. The words of Levi/Bergmann/Allen are spoken periodically by Dr. Bergmann through the film on a flickering screen.

He concludes the film by holding out the hope that, despite Allen’s despair about the absence of a moral structure (one of the subjects of the film), “Most human beings seem to have the ability to keep trying to find joy from simple things like their family, their work, and from the hope that future generations might understand more.” Paradoxically, he suddenly commits suicide. His final words of hope and optimism about the human condition run after we know he is dead.

The first time I visited Dr. Bergmann for an interview, he was ill and my appointment was rescheduled. On my second visit, before I could see him he was again taken ill, and he died later that day. Several weeks later I met with his widow, Dr. Maria Bergmann, who was 95, and their son, Michael Bergmann, a screenwriter, director and producer. “My husband was at first dismayed by [professor Levi’s] suicide,” she told me. “Woody came and talked to my husband here. Woody let him speak his own words at the film’s conclusion because my husband said that the final words of the film had not really represented his views. And so there are a few words at the very end which are completely my husband’s. Those words replaced what Woody had written before. Woody allowed them to stand.

“One scene was supposed to take place [with] my husband and Woody walking in the park. But it never took place. Because Martin, who was much older, felt fine. But Woody Allen was cold. So that scene never took place.”

Maria Bergmann shared with me an exchange of letters between Dr. Bergmann and Allen. Dr. Bergmann wrote that “I am nowhere to be seen [in the film]. … And yet the impact of my work is felt throughout the film. … Acting was never part of my fantasy life, but I can say that working with you was as close as a man my age can come to playing. So for that too I want to thank you…”

Allen replied with both a warm appreciation of Dr. Bergmann and a joking reference to himself:

Dear Professor Bergmann,

Thank you for your note. I’m glad everything went well for you in your cinema debut. I wish I had known you earlier in my life, before I began the last 25 years of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. You might have been able to cure me.

Best,

Woody Allen.

I have had fantasies of my helping Woody achieve his masterpiece, a film that somehow tackles the Holocaust and Israel but without the lachrymose, lugubrious touch that has sometimes marred his work—the “anhedonia” factor. This would be a film that would emerge out of his deepest concerns and obsessions—the fount of most great art. He gets the balance of comedy and drama so right in Crimes and Misdemeanors, Purple Rose of Cairo, Zelig, Midnight in Paris, Alice, and Husbands and Wives. Sometimes he makes his dramatic point only comedically, as in Bullets Over Broadway, where the mafioso Cheech is the true artist and kills Olive, the actress in the play he is secretly writing, because her squeaky voice is “ruining my play.” The true artist, Allen is saying, will do anything to achieve his artistic goal.

This fantasy of mine of helping or influencing Woody has intruded into reality. I have left him hints—Xeroxed articles in a little package with a copy of my novel, The Great Kisser. There was one from the Jewish Review of Books by Stuart Schoffman about Mickey Cohen’s fundraiser for Palestine in Hollywood in 1948 at Cohen’s nightclub, Slapsie Maxie’s Cafe (the ex-fighter Rosenbloom was a front for Cohen), which was attended by a full house of wiseguys, bookies, and ex-prize fighters. Ben Hecht addressed the audience of 1,000 in a plea for the soldiers of the Irgun. Some Damon Runyon characters also spoke: “Come on, you mugs, give,” or words to that effect. It seems to me that here is the basis for what Allen does best: a balance of comedy and drama in the service of a moral issue, with the Holocaust and Israel as the critical backdrop and underlying themes. In an equally sly fashion, I deposited for Allen sections of Aharon Appelfeld’s great memoir, Story of a Life, selecting sections that touch upon one of Appelfeld most poignant and central themes: the joy and gusto with which the Nazis and their collaborators found the fulfillment of a lifetime in killing Jews. These are the kinds of documents and books I read all the time, and I have come to the conclusion that Allen doesn’t—although he spoke with me about such great works of the Holocaust as Lucy Dawidowicz’s The War Against the Jews and Victor Klemperer’s Diaries.

I realize as I’ve written this piece that it is a somewhat darker study of Woody than my book presented. The biographer is confronted with a choice: to let the subject’s work be the final verdict, or to let the ambiguities and complexities—sometimes disturbing ones—of character subsume the lifetime of work that the subject has contributed to the world. And there have been few studies of Allen—most notably Stephen Bach’s Final Cut—that deal sensitively with Allen’s character and integrity. I felt that more of that aspect of him was needed. But there is no doubt that Allen is selfish and self-absorbed. So there’s always the need to rectify the balance. And inevitably there’s a shift in perspective and balance with the passage of time.

There was a time when I hoped to run into Woody in Central Park, just as I previously hoped to run into Tony Bennett there. Both are lovers of the park and of the city; in fact, it’s startling that I chose to write about two men with some of the same loves, lusts, and passions, the same devotion to their art, and the same longevity of talent. Nevertheless, I no longer hope to run into Tony, and if I run into Woody, I feel that we will resume the conversation we began in his screening room with ease and pleasure. After all, his anxieties are my own. We are brothers in trivial suffering. I can be sure that if I run into him, he will be worrying about something with the same intensity that I am worrying about something else. Who can feel anxious with such a person?

The other day, my tailor replaced a missing button for my trousers with a larger one. I could not insert the button into the hole for some 10 minutes. When I got to my office, I could not unbutton it. I realized I could not go to the bathroom because of that fucking button. I grabbed scissors and poked and poked at the hole to try to enlarge it. No such luck. And not a good idea. I cursed God, my luck, my parents—who gave me nothing but panic and fear—my life. How could this happen to me?

Woody Allen was a perfect subject for me. And the enormity of his achievement stands.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

David Evanier is the author of Woody: The Biography; All the Things You Are: The Life of Tony Bennett, The One-Star Jew, The Great Kisser and six other books. A former senior editor of The Paris Review, he received the Aga Khan Fiction Prize and has appeared in Best American Short Stories. He is working on a book about the Fortune Society.