Between Two Worlds, Belonging to Neither

New editions of the enduring scholarly work of Philipp Jaffé, the Polish Jew who was a groundbreaking German medievalist

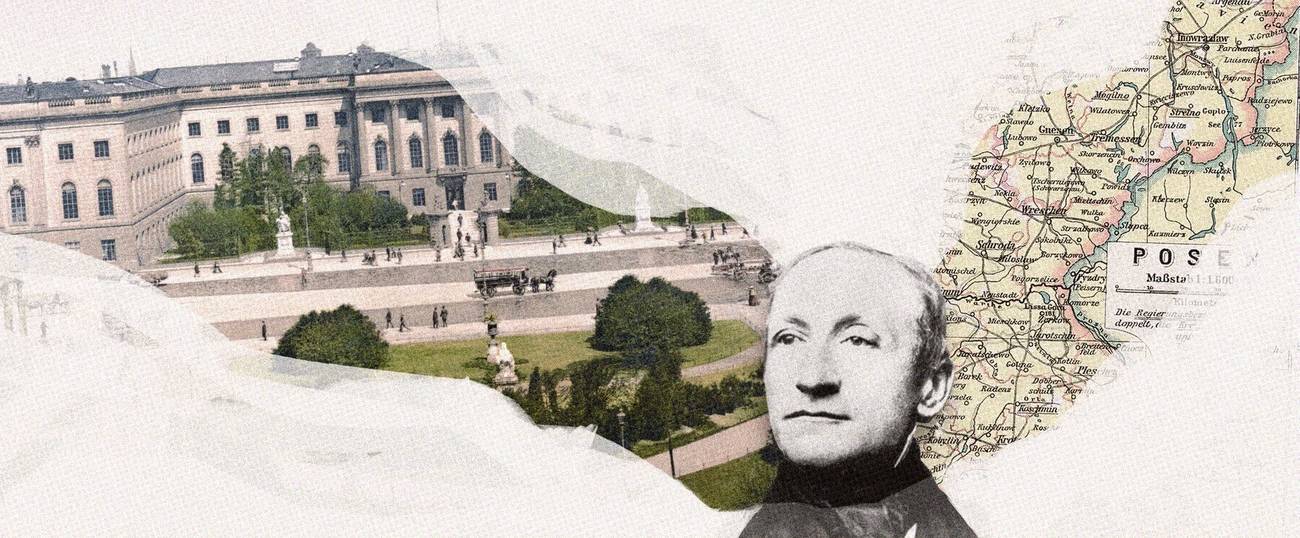

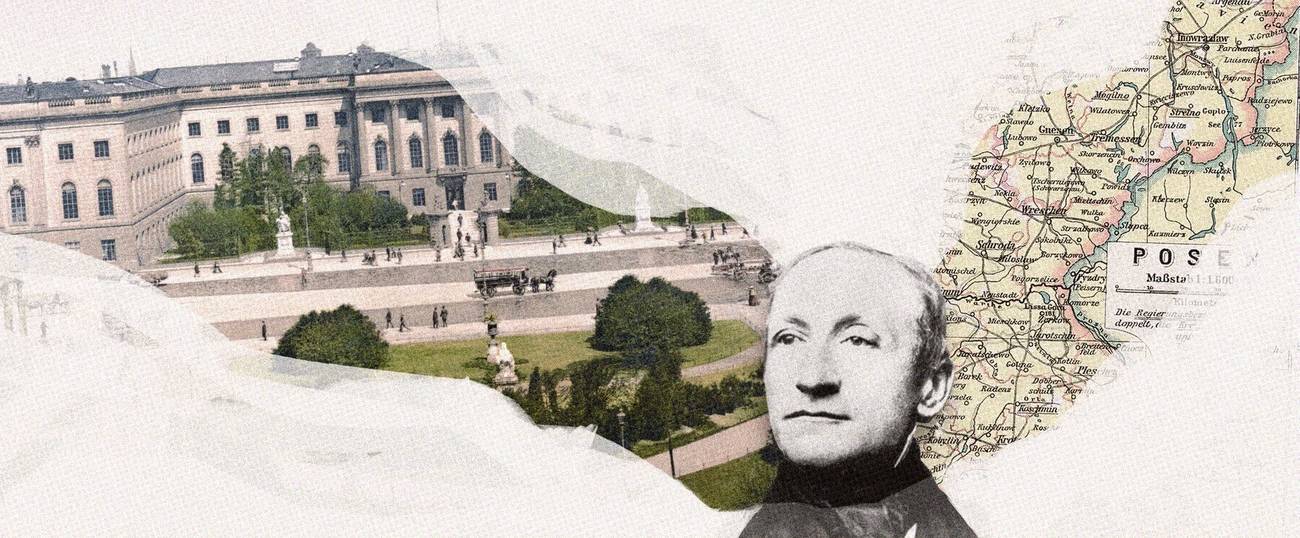

Philipp Jaffé (1819–1870) was one of the 19th century’s foremost historians of medieval Germany. After some false starts with monographs, he found his métier as a philologist—discovering, identifying, transcribing, and elucidating Latin texts that constitute the raw material for reconstructing medieval German history. And his work has survived the test of time. His magnum opus, Regesta pontificum romanorum (1851), a 900-plus-page compendium of summaries (“regesta”) of more than 11,000 papal documents down to 1198, is still a standard tool of medieval studies; a second edition was published by a team of scholars in 1885–1888 and a third edition has recently begun to appear, the fruit of long years of work by the “new Jaffé” project of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. Similarly, the six volumes of Jaffé’s Bibliotheca rerum germanicarum (1864–1873), averaging some 700 pages each, remain standard anthologies for the topics to which they are devoted, and were reprinted in 1964; and the list of his publications, in the online Regesta imperii bibliography, runs to more than 130 items. Not many scholars have left oeuvres that can compete both in their dimensions and in their lasting vitality.

Moreover, Jaffé lived and worked in Berlin in the inner circle of the hub and pinnacle of German historical scholarship in its formative years. He was among the prime students of Leopold von Ranke, one of the founders of modern historical scholarship; he was first the protégé, then the employee, and finally the embittered competitor and enemy of Georg Heinrich Pertz, who for more than half a century was at the helm of the prestigious Monumenta Germaniae Historica research center; and then he was the friend, protégé, and collaborator of Theodor Mommsen (1902 Nobel laureate in literature), one of the central figures of ancient and early medieval studies. As such, a study of Jaffé’s life and work helps fill out the history of a major component of German scholarship, one which, given its focus on the heroic past of the German Reich in the Middle Ages, played an important role in Germany’s self-image, and fateful sense of national mission, in the 19th and 20th centuries.

However, Jaffé was not the usual Berlin medievalist. He was a Polish Jew. He was raised in a very Jewish context, and continued, to a significant degree, to live in such a context, or at least to maintain intense contact with it, long after his move to Berlin and entry into the so very non-Jewish world of German historical scholarship. He was born and spent his childhood in Schwersenz, a town near Posen of which half the population was Jewish; his family’s name marked it as having illustrious rabbinical roots (the family of R. Mordechai Jaffe [“the Levush”] and R. Joel Sirkis [“the Bach”]); when he corresponded with his grandparents it was in German but in Hebrew script; and although he would soon be sent to Posen for his Gymnasium education, years later he would fondly recall, in one of his letters, how, every weekend, some Schlomche would bring him cakes from his grandmother. Similarly, when his father, a businessman, sent him for an apprenticeship in business in Berlin in 1838, it was to a Jewish banker, and Philipp lived in a heavily Jewish neighborhood; his first historical publications were on medieval Jewish history; his letters over the next decades are full of references to relatives and other Jews visiting from Posen or, like him, living in Berlin; hardly a Jewish holiday goes by that he does not write his parents, or his sisters, to thank them for the traditional cake or other treats that they sent him to mark the holiday; and as late as 1866 we find him chatting with Leopold Zunz at a party sponsored by the Jewish community of Berlin in honor of one of its rabbis. Jaffé’s life, illuminated vividly by the 229 letters of 1838–1870 collected in Between Jewish Posen and Scholarly Berlin: The Life and Letters of Philipp Jaffé, is thus one of the better documented lives of a Polish Jew who, like so many others, moved west, and into western culture, but continued to be identified as a Jew.

What is fascinating about Jaffé is the extreme way in which he was neither simply a German medievalist nor simply a Polish Jew. While others integrated their different identities, or maintained them irenically or even fruitfully alongside one another, Jaffé did not. Rather, each of them, frustratingly, prevented the other from fulfilling its potential. He could not have the regular career of a German medievalist because he was a Jew and, accordingly, unable to obtain a regular university appointment; and, almost to the end of his life, he disdainfully refused to convert to Christianity, lest it be thought he did so to further his career. Nevertheless, he applied prodigious energy toward being the most productive medievalist of his day and, concomitantly, he developed antipathy and scorn toward lesser scholars, especially when their formal status was higher than his. But his devotion to the study of history also separated him from his Polish Jewish family: his vocation to “the muse that I serve—history,” to “the objects of my study, which make my life worth living,” kept him busy, in Berlin during the year and on the road every summer (traveling from library to library, and from monastery to monastery), day and night, year after year. The contrast between the obviously heartfelt expressions, in his letters, of his love for his parents and sisters in Posen, and of his yearning to see them, on the one hand, and the years and years that went by between his visits to Posen (although it was only a few hours by train from Berlin), on the other, is stark and tragic.

Never fully accepted into the historians’ guild (although eventually gaining an adjunct position in the University of Berlin), but equally unable to remain fully a part of the Jewish world into which he had been born, Jaffé lived a lonesome life. He never married (and wrote frankly of his fear that children might bother him in his study); he had few friends and, it is reported, as time went on he limited his contact with them to scholarly issues; he had few students; he spent long days working alone in his Berlin apartment, and long summers traveling all around Europe to copy manuscripts; and, eventually, he became entangled in a bitter feud with his erstwhile patron and employer, Georg Heinrich Pertz and, perhaps more fatefully, with Georg Waitz of Göttingen, a Pertz protégé who was Jaffé’s only real competitor in Germany. By the late 1860s, although he was still widely recognized as the final authority concerning controversies regarding the authenticity and interpretation of medieval documents, he apparently had had enough of this life, and of being a Jew. Already in 1864 he had suffered something of a burnout, and although he recovered from it and returned to his labors, the feud with Pertz, and his workaholic habits, continued to take their toll. After his father, to whom he was devoted, died in 1866, leaving him all the more alone in the world, Jaffé was baptized in 1868, and two years later he killed himself. As his friend, patron, and frequent collaborator Theodor Mommsen would put it, a few days after the suicide, “nothing blemishes Jaffé’s memory; the only thing one might accuse him of was of being tired of life.”

Jaffé’s death had two important indirect repercussions. It played a role in the demise of Pertz’s regime at the Monumenta, and the fact that Jaffé’s major disciple, Max Lehmann, was left “orphaned,” forced him into a new career which, within a few years, was to have a major role, hitherto unnoticed, in the rise of modern anti-Semitism. Namely, after Jaffé’s death Lehmann desperately and calculatingly sought a new patron, and, moving from medieval history into modern history, soon became a research assistant of Prof. Heinrich von Treitschke. While Treitschke is generally recognized as having inaugurated modern “respectable” anti-Semitism in Germany, for it was his 1879 essay that attacked Heinrich Graetz and the Jews of Germany in general that touched off the intense “Berliner Antisemitism Dispute,” it has not been noticed that the very copy of Graetz’s Geschichte that Treitschke read was lent to him by Lehmann, who had written an angry review of it late in 1870, a few months after Jaffé’s death—and that comparison of the topics and formulations of their attacks on Graetz clearly shows Treitschke’s dependence on Lehmann. Had his Jewish mentor, Jaffé, still been alive, Lehmann would most probably not have written so nastily about Jews, and he certainly would have had no reason to seek out Treitschke. But then Treitschke might never have seen Graetz’s volume or Lehmann’s review of it, and the history of German anti-Semitism would not have been the same.

Jaffé’s life remains, however, as an exemplum of how total devotion to scholarship can be fruitful but not without its severe personal costs; how a gifted individual who tried to move from a Jewish context into a non-Jewish one without fully leaving the former can find himself alone and stranded between the two; and how the energies catalyzed by such isolation and frustration can engender an oeuvre of astounding proportions and enduring value.

***

Adapted from Daniel R. Schwartz, Between Jewish Posen and Scholarly Berlin: The Life and Letters of Philipp Jaffé (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2016). All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the copyright holder, Walter de Gruyter.

Daniel R. Schwartz is the Herbst Family Professor of Judaic Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He specializes in ancient Jewish history. He was drawn into this project on a nineteenth-century medievalist apropos of his study of Heinrich Graetz’s changing views on the Jews of antiquity in general, and on Flavius Josephus in particular, between the second (1863) and third (1878) editions of the third volume of Graetz’s Geschichte der Juden.