Cartooning the Jews

A new survey brings to light the late-19th and early 20th-century history of vicious American anti-Semitic caricature

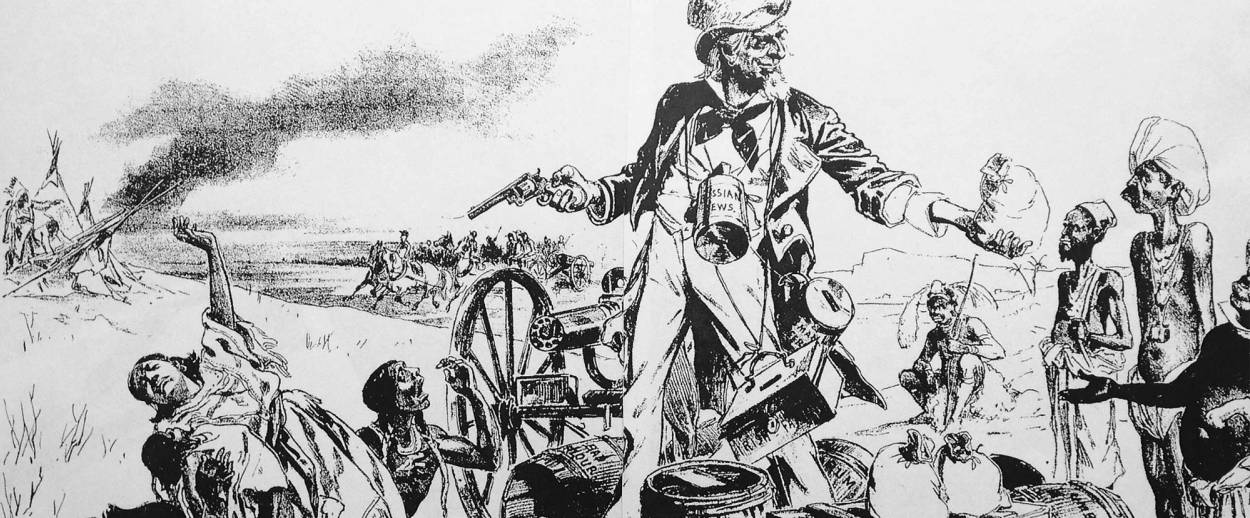

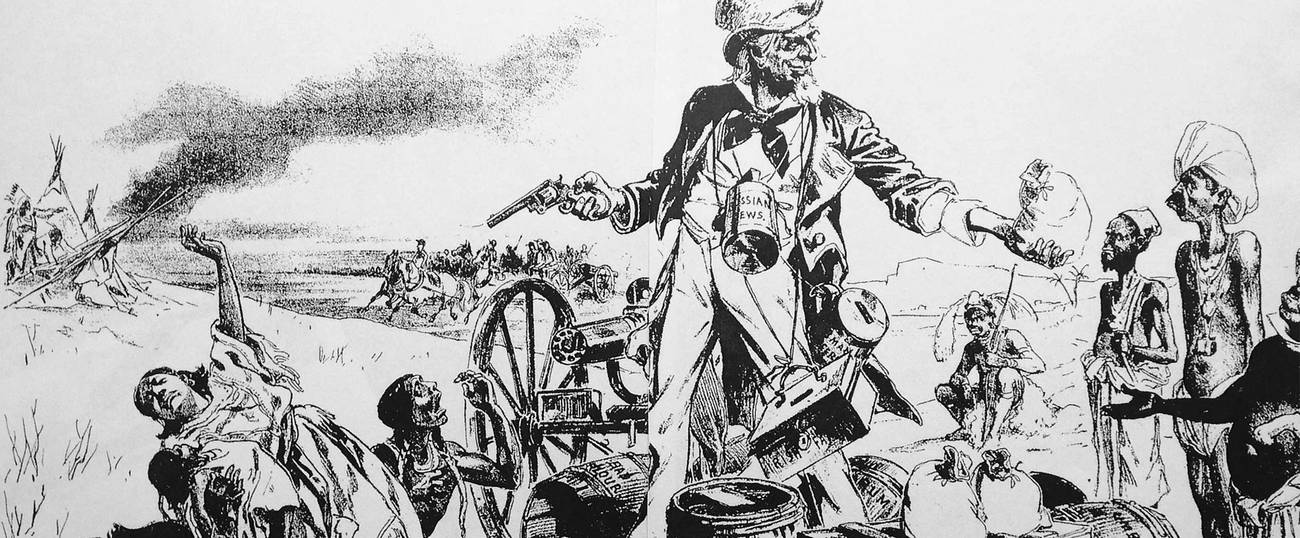

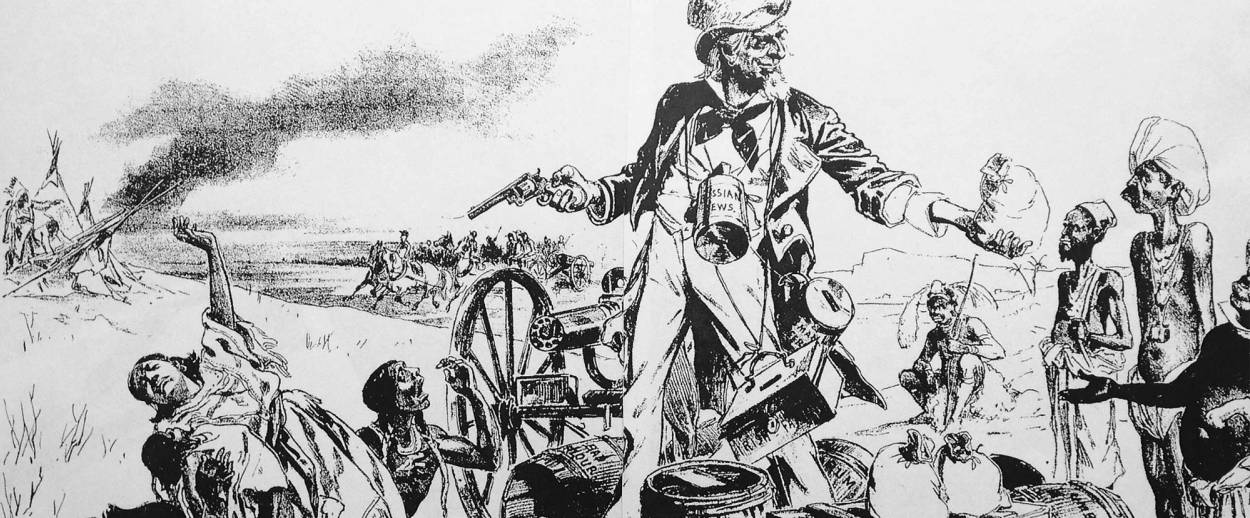

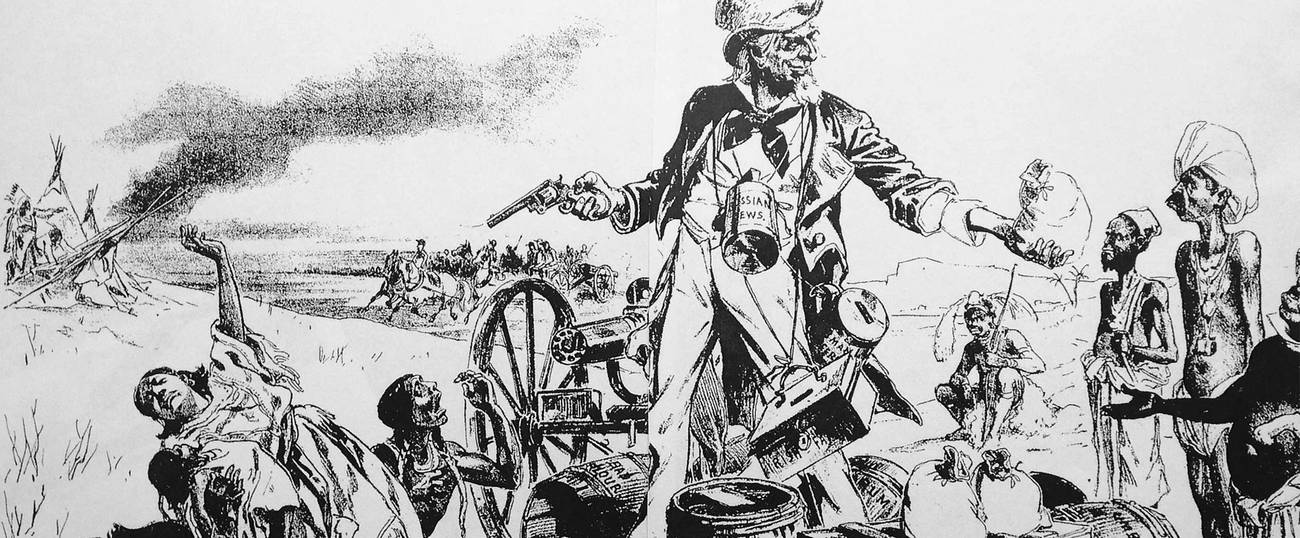

In preparing my book, The Implacable Urge to Defame: Cartoon Jews in the American Press, 1877-1935, I looked at thousands of cartoons in magazines such as Puck, Life, Judge, and Judge’s Library that included offensive and malevolent images of Native Americans and African-Americans as well as immigrants especially from Ireland and Eastern Europe. But a casual glance through a few issues of any one of these magazines clearly indicated that a strong anti-Semitic bias was present and undeniable. Cartoonists attacked Jews more scathingly and with more hostility than other groups not only by harping on a few Jewish bodily stereotypes such as having huge noses, pot bellies, and bowed legs but by showing Jews to be criminals, corrupt businessmen who set fires to collect insurance, who gloated over good business deals, and took advantage of bewildered customers. Jews were, as well, unprincipled social climbers intent on teaching their children that making money should be their basic desire in life. Captions were written in broken English as a way of distancing immigrants from mainstream readers and inferring that recent immigrants might not be able to assimilate, let alone become decent American citizens.

Most cartoonists for Puck and the other large-circulation humor magazines probably had minimal contact with Jewish immigrants. So their cartoons were based on little or no knowledge as well as misinformation about their subjects, which was passed on to their readers. Who, then, were the Jews represented in these cartoons? They were people intent on gaming the system. They were immoral and criminal-minded from the get go. In fact, in the 1860s, so many fires were reported to be started by Jewish businessmen that insurance companies would not insure their businesses until it became clear that this was, as we would say today, fake news.

Set apart from honest, hard-working mainstream Americans by their disreputable activities, Jews were further distanced by the way cartoonists mangled their laughable English pronunciations in the captions. Freud, other psychologists, and even modern, contemporary cartoonists who have tried to explain their own intentions agree that creating cartoons is a way to discharge hostility without resorting to physical violence. Cartoons also make certain that cartoonists and their audience are insiders while the subjects of the cartoonists are outsiders who are belittled, diminished as individuals, and not to be admitted to or at least kept at a distance from insider culture. It often is an us-versus-them conflict. In addition, where Jews are involved, there was always the factor of perennial anti-Semitism or, to be blunt, Jew hatred. As a result, cartoonists and their cartoons were divisive rather than helpful or supportive in integrating immigrants into American life.

With so many negative cartoons published over the decades, it can be argued that these contributed to the fears of many mainstream Americans who felt that immigrants, especially those from Asia and Eastern Europe, would compromise the American gene pool, create political unrest, take jobs away from “real” Americans (read: those of Anglo-Saxon heritage), and change the nature of whatever was termed the American character.

I wrote The Implacable Urge as a companion to my 2015 book, Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art, 1880-1940, in order to contrast attitudes of Jewish artists and mainstream artists toward the Jewish presence in late 19th- and early 20th-century America. Cartoons in magazines served as illustrative material because these seemed closest to the nation’s pulse. Illustrations for Social Concern appeared, for the most part, in Yiddish and English-language liberal and radical magazines, and those for The Implacable Urge were taken from mainstream humor magazines. Illustrations in both books date from the 1870s to the 1930s.

Heretofore, many Jewish artists prominent in left-wing art movements were considered to be strongly swayed by Communist rhetoric. The premise of the earlier book differed from that notion and revolved instead around the idea that socialism—the desire to help others—was a secular version of Judaism that artists had absorbed in their youth. I argued that the artists, mostly born in Eastern Europe, were influenced initially and most importantly by their Jewish religion and Jewish cultural heritage that called for helping others in need. Left politics provided them with a secular framework for their concerns and interests because it coincided with social and religious values they had learned as youngsters. Their cartoons criticizing governmental policies as well as in support of better working and living conditions through labor union and political activities were affirmations of attitudes they had internalized as children.

The content of The Implacable Urge to Defame grew from the opposite premise—that Jews were destructive to mainstream American values, that they helped nobody but their own personal interests. Both books, then, project opposing attitudes toward Jews and their place in American history—friendly and humanitarian in the earlier one, venomous and threatening in the second. The material explored in these two books has been largely ignored in American art history.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Matthew Baigell is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University. He is the author of numerous books, including American Artists, Jewish Images, and Jewish Art in America: An Introduction.

Matthew Baigell is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University. He is the author of numerous books, including American Artists, Jewish Images, and Jewish Art in America: An Introduction.