The Menorah as Symbol and Myth

A recent joint exhibit at the Vatican Museum and the Jewish Museum of Rome traced the surprising and enduring significance of the seven-branched golden object that entered ‘the temporal web of the history of humankind’

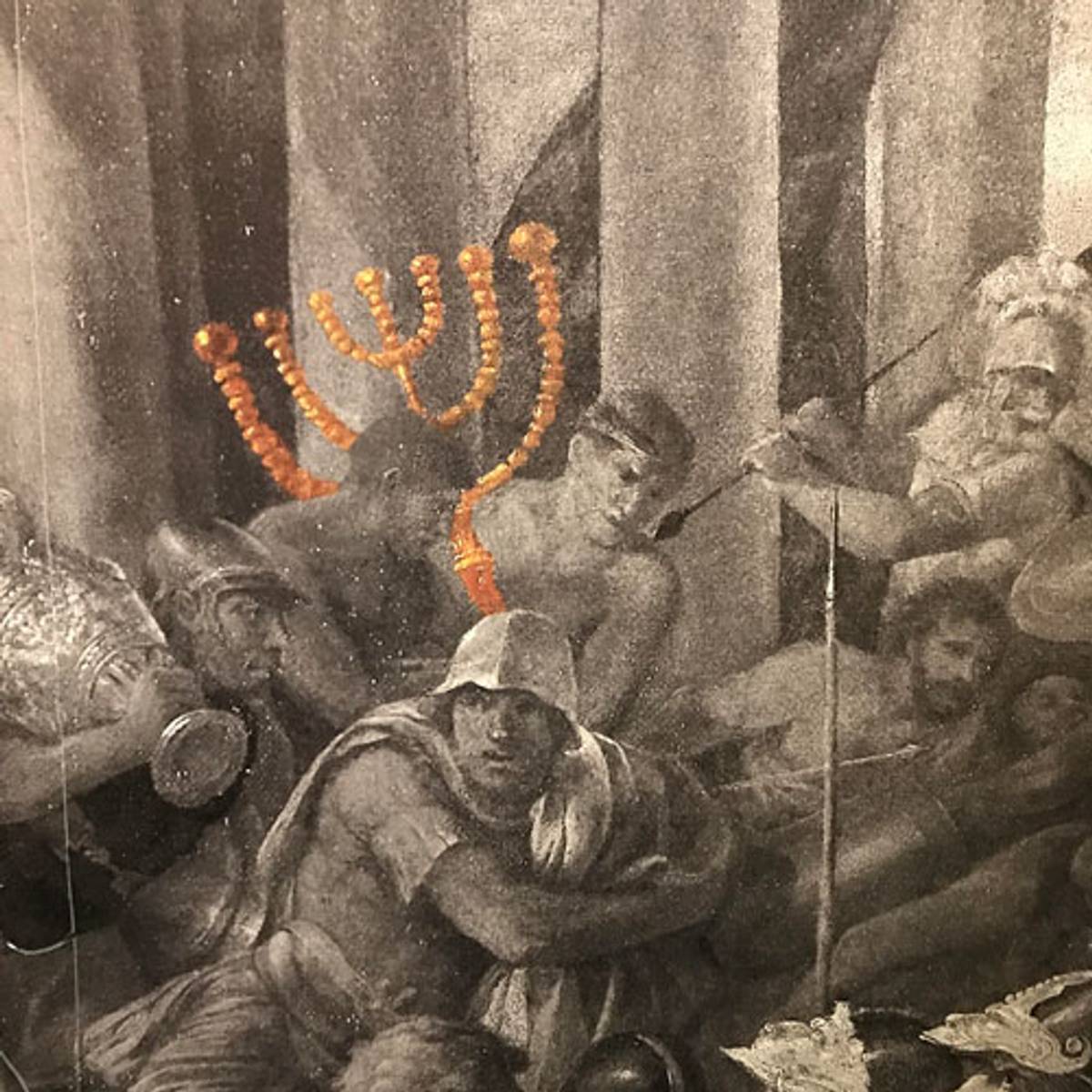

In Rome, the past is always underfoot—and overhead. For Jews, in particular, during the last two millennia, the past has been prominently, sculpturally, and hauntingly overhead in the Arch of Titus, whose southern relief famously depicts a procession of Roman soldiers bringing to the capital the seven-branched menorah that was plundered, along with other ceremonial objects, from the Second Temple in Jerusalem when General (later Emperor) Titus defeated the city in 70 CE. This one carved image cemented forever after the destruction of the Jewish state and the inauguration of the Jewish diaspora.

The menorah on the Arch of Titus has held such a grip on the Jewish imagination that for much of these two millennia Jews have superstitiously avoided passing beneath it. Only with the founding of the state of Israel in 1948, when the chief rabbi of Rome led a procession under the arch (in the opposite direction from which Jewish prisoners were paraded 2,000 years earlier) was the superstition countermanded, but even to this day the menorah seems to convey an almost magnetic charge.

What is this object, and why does it matter so much, both on the Arch of Titus and elsewhere? How the menorah became the fundamental symbol of Jewish identity and persisted as such from the very beginnings of the religion was the subject of the first collaboration between the Vatican Museums and the Jewish Museum of Rome. These two institutions came together to organize The Menorah: Cult, History, and Myth, an exhibition unevenly divided between both museums (for spatial reasons, more material was on view at the Vatican) that told through objects and images what curator Francesco Leone in his catalog essay described as “one of the most captivating stories of the human race.”

As with any good museum show worth the effort of its mounting, The Menorah teased out and refined conceptions and misconceptions that have adhered to the menorah from the moment when God showed Moses an image of a seven-branched oil lamp on Mount Sinai and ordered him to forge this object in pure gold. According to Exodus, a talent (34 kg) of gold was melted down and beaten into a lamp that represented a stylized almond tree with buds, corollas of petals, and fruit. (Naturally, there are other, somewhat conflicting biblical accounts, but it seems safe enough to go with this one.)

From the moment the menorah was placed in King Solomon’s Temple sometime between 967-961 BCE, it entered, in Leone’s felicitous phrase, “the temporal web of the history of humankind.” The menorah remained in the First Temple until 586 BCE, when the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple, carried off its treasures, and in the process presumably melted Moses’s menorah down for its gold—“presumably” because, being prone to abundant legends, even this original menorah has been thought (or rather: hoped against hope) to have survived hidden in the foundations of the First Temple, where it still awaits discovery.

Whether Moses’s menorah was actually saved or, more likely, newly fabricated, a golden menorah was on hand when the Jews returned from their Babylonian exile and built the Second Temple (535-515 BCE). This is believed to be the menorah described in Zechariah’s fifth vision as being “all of gold, with a bowl upon the top of it, and his seven lamps thereon, and seven pipes to the seven lamps.”

Before Titus, the other key beat in the early history of the menorah, of course, took place in 167 BCE when Antiochus IV sacked Jerusalem and consecrated the altar to Zeus, an act of forced submission to paganism that provoked the revolt in 164 BCE of Judah the Maccabee. As recounted in the Talmud, a vial of oil that managed to survive in the deconsecrated Temple was expected to last for only one day but instead burned for eight—and voilà: the incident that begets every Sunday-school student’s masterwork in modeling clay and finger paint (though augmented to nine, rather than seven, branches).

And then came Titus. His removal of the menorah from the Second Temple is the first event in the biography of the menorah for which we have a nonbiblical source in the form of an eyewitness account written in the first century by the Jewish Historian Flavius Josephus. Josephus was with Titus during the siege of Jerusalem, saw the arrival of the troops there, and afterward accompanied them to Rome. In War of the Jews, he described a “candlestick of cast gold, hollow within, being of the weight of 100 pounds” and decorated with “knops, and lilies, and pomegranates, and bowls … elevated on high from a single base” and terminating “in seven heads, in one row, all standing parallel to one another; and these branches carried seven lamps, one by one, in imitation of the number of the planets.”

The actual Jewish menorah, captured in precise, descriptive language from antiquity by someone who very likely saw the object itself, both before and after it was taken from Jerusalem: fantastic.

***

These paired museum exhibitions did a handsome job of unpacking some of the running menorah themes, let’s call them, that are wound into Josephus’ description.

Consider some of the most basic facts about the object, for starters. Why seven branches? Josephus mentions the planets (six in orbit around the sun); but there is also, he adds in a later passage, “the dignity of the number seven among the Jews”—derived from the six days of creation plus the Sabbath. Why lilies and pomegranates but no almonds? This would seem to be a confirmation that Moses’ menorah was, in fact, melted down after the destruction of the First Temple, and a new one, in a revised form, was fabricated later. Josephus describes the oil lamps lined up “in one row”; yet lampstands that were made around the time of Moses were more often arranged in three-dimensions, with individual lights circling a single bowl. Here there would seem to be still further proof that what Josephus saw was the successor menorah.

And then there is the fascinating puzzle of the menorah’s base. Josephus asserts that the Romans had modified it so that “its middle shaft,” he says in his account of the procession, “was fixed upon a basis.”

The menorah that was rescued from the Second Temple after it was set on fire by one of Titus’s soldiers—pointedly, the story goes, not by Titus himself, who was said to be against its destruction (see his troubled expression as depicted in two narrative paintings by Nicolas Poussin from the early 17th century)—stood up on a tripod, a detail confirmed by dozens of representations on view in these exhibitions. However, the menorah on the Arch of Titus is set in a hexagonal ferculum, or box, that was carved with animals and mythological creatures, in obvious defiance of the biblical injunction against graven images.

What happened? Clearl, the base of the menorah was changed before it arrived in Rome—but why? One obvious explanation is that, since a candelabrum that rests on a tripod is not easy to balance when being paraded through the streets of a raucous city, the event planner of the era decided to commission a new base for it. So there was a practical motivation. But decorated animals? Mythological figures? The Romans were perfectly capable of manufacturing unornamented bases for works of art. Why not for the menorah? It’s hard not to believe that this gesture is a subtle visual reinforcement of the Romans’ having captured—boxed in, if you will—the Jewish people and their key religious symbol. You may be different from us, this one modest but key modification says, but you are part of us; you are ours now.

It’s interesting to note that in the many depictions of the menorah that began to proliferate after Titus brought it to Rome, the original tripod base was retained, as if to suggest—what? Defiance? Longing? Hope? Or was it something simpler, such as a habit of adhering to an already-set symbol in the collective Jewish imagination?

As interesting, in its own way, is the choice made by Gabriel and Maxim Shamir, the artists who designed the menorah that in 1949 became the emblem of the State of Israel: they decided to retain the Roman base (though in a stylized form). It’s a different idea of defiance, perhaps: You may have boxed us in, the emblem seems to suggest, but in the end we prevailed.

***

Origin, form, material, symbol, meaning—what’s left but fate?

Titus, we know, delivered the menorah to Rome in 71, where its arrival was forever after commemorated by Domitian in the arch he erected after his brother’s death in 82. (Recent noninvasive spectrometry readings, by the way, have found traces of gold paint on the menorah and blue on the sky behind, yet another reminder that the tastefully austere monochromatic Rome we see today is markedly different from the vividly colored city of antiquity.) The procession delivered the menorah to the Temple of Peace in the Forum of Peace, which was erected by Vespasian and paid for with booty taken from the Jerusalem Temple (which also helped fund the Colosseum). “Displayed in bleak triumph,” as Leone put it, the menorah was often seen in its new home, and commented on, by visiting rabbis, and it was depicted—sometimes accompanied by other symbolic objects, such as the etrog, shofar, palm frond, or amphorae to hold oil—in catacombs, synagogues, tombstone inscriptions, graffiti, glassware, jewelry, mosaics, and (in later periods) paintings, textiles, and manuscripts.

The Temple of Peace was damaged by fire in 192 CE, and here the fate of the menorah begins to drift into shadow. If it survived the fire—testimony is scant—it is possible that the menorah was plundered by Alaric, king of the Visigoths, in 410, after which it maybe fell into riverbed where Alaric suddenly died. Or perhaps it survived until the arrival Genseric’s vandals in 455 and was taken to Carthage, the new capital of Vandal kingdom.

Other speculations and legends suggest that the menorah never left Rome but was hidden among the reliquaries in the Lateran Basilica (a mosaic inscription says it’s so!). Others still speculate that it was secreted in the remote reaches of the Vatican. Particularly intriguing is a gravestone in the exhibition that describes three Jewish brothers who were executed in the fifth century CE under Emperor Honorius after apparently having seen the menorah at the bottom of the Tiber—it turns out to be a 19th-century fake, an imaginative bit of myth-making that coincided with the opening of the Roman ghetto in 1870.

“There is an almost magical aspect to the menorah,” observed Alessandra di Castro, one of the curators of the exhibition, which built on a smaller show that was mounted in Rome in 2008 by her sister, Daniella di Castro. “It is just so significant, this one thing that for 3,000 years has meant so much to us Jews.”

And not only the Jews: As a form, the menorah reappeared—you might even say it was reincarnated—during the Middle Ages, when Charlemagne cemented his authority by hinging his dynasty to both the Roman emperors and to ancient Jerusalem. Striking examples of menorah-like candelabra (in both three-dimensional and linear shapes) began to proliferate in churches, further underscoring the power of this object, which has lasted all the way to the modern era, when Stefan Zweig wrote a novella about it, Chagall painted it, Matisse sketched it, and just last year, William Kentridge erased it in the dirt on the travertine embankments that frame the Tiber, a form of reverse graffiti that will one day simply fade away to nothing.

As a drawing in soot, the menorah may be evanescent, but as a religious symbol, it doesn’t look like it’s going anywhere. From Moses forward, it has been worth its weight in gold—many times over.

***

Read more on the Vatican’s relationship to Jews in today’s Tablet magazine.

Michael Frank is also the author of a memoir, The Mighty Franks, and What Is Missing, a novel.