Double Exposure: Jean-Pierre Melville

The ambiguities and darkness of Nazi-occupied France propelled him to flee his country, take a new name, fight in the Resistance, and then invent film noir. But the past continued to haunt him.

I’m drawn to abstractions, and a name is the most abstract thing in the world. —Jean-Pierre Melville

Call him Melville. He picks his way through the rubble, skirts along charred walls, climbs over a roof beam here, steps on a windowpane there, bits of glass scraping underfoot like the screak of winter snow. He moves through interconnecting alleyways as through the maze of a Moroccan souk, sheer-sided as a prison perimeter, buttressed by fire-blackened metal uprights. A ladder much too short to scale a particular wall leans its lacquered wood against the pitted limestone, scored and scraped by tortured ghosts. A vacant lot in the 13th arrondissement, it looks from above like a concrete maze ringed by three- and four-story buildings. The surrounding dilapidation, the washing hung from the windows, mark the precincts of his “cobbler’s stall,” as he liked to call his movie studio.

Only the outer defenses of the fortress are left, tracing the rue Jenner and the rue Jeanne d’Arc, a ghost town of 12,000 square feet looking just like something from a modern western, between the elevated Chevaleret Métro stop and La Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital. A corner of America, a fantasy drawn straight from a Sinatra song, the streets are lined with fences that hide vacant lots and shadowy dealings. Debris collects in pyramids, boards, broken furniture, segments of doors, tangled with lengths of twisted metal. His Ford Mustang is parked in front of the local bar, its state-of-the-art cassette player oozing Miles Davis, a car sequence from Elevator to the Gallows.

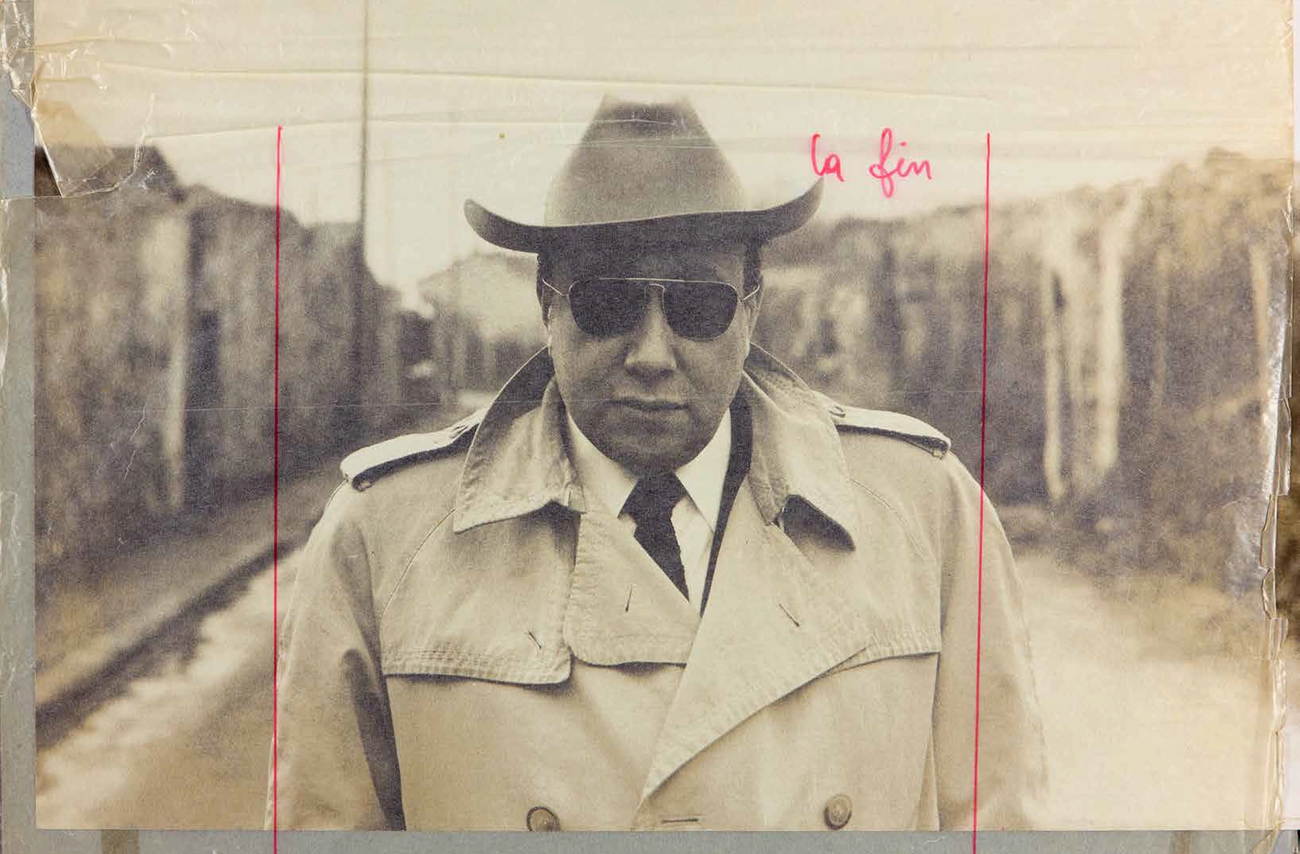

Jean-Pierre Melville walks down the central alley sporting a Stetson, Ray-Ban shades, and a trench coat, personification of the lone sniper who curses his fate, curses the plots to bring him down—him, the solitary man. In a huge room, the scarred plaster of its walls flaking, he stops and savors fire’s random opus: “This lovely abstract composition was made by the fire, and I think that Cocteau would have found it very beautiful. I mention Cocteau because in 1949 I had a small set in this exact spot, a small auditorium where I shot the greater part of Les enfants terribles, and I remember making Cocteau run around the microphone before recording his heartbeat. That’s the heartbeat you hear in the film.”

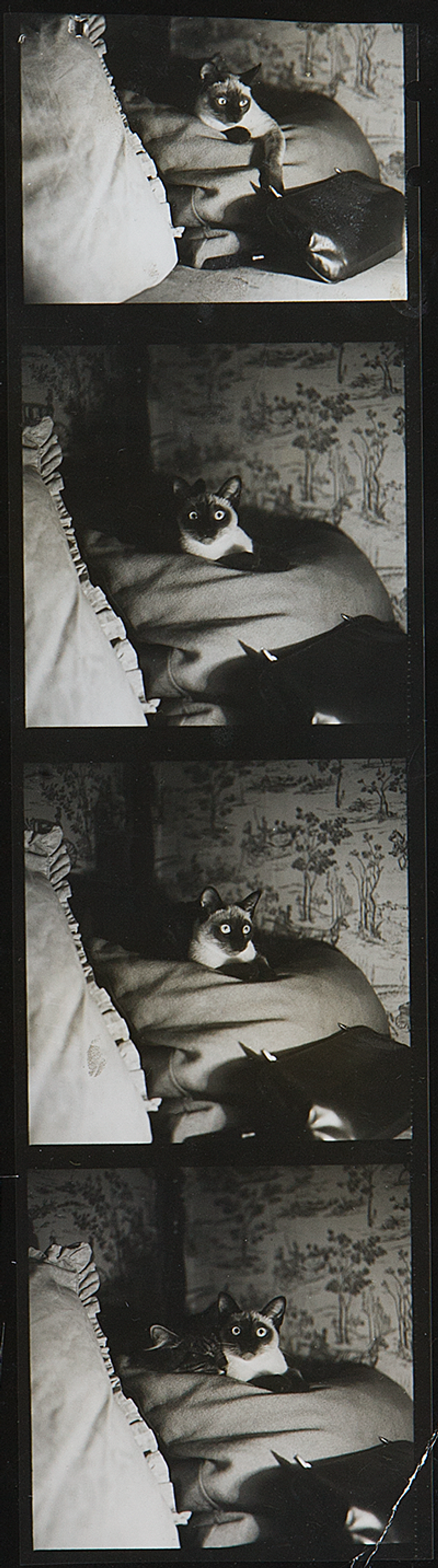

It is 1970. The studio on the rue Jenner burned down three years ago, on June 29, 1967, during the filming of The Samouraï. The abandoned factory, converted in 1955, caught fire in the middle of the night. Melville is asleep, alone, his wife, Florence, is away. The heavily lined curtains, the close-fitting shutters, plunge the apartment at 25 bis rue Jenner into a deep pit of darkness, which the man in dark glasses mistrustfully supplements with a sleeping mask. While Melville sleeps, blanketed in double darkness, fire spreads through the apartment. His Siamese cat, Amok, wakes him, one of Inspector Mattei’s cats in Le cercle rouge, its photograph tucked in a cardboard box. Melville rouses himself, escapes the flames, watches helplessly as his kingdom is destroyed. Dazed, lost in bitter reflections over the past and anxiety over the future, he realizes that he has left Amok and a precious souvenir from the past behind, prisoners to the flames. He re-enters the studio, now a blazing inferno, climbs to the second-floor apartment, grabs the Siamese cat in one hand and a signed picture of General de Gaulle in the other. Nine fire brigades battle the fire for two hours before bringing it under control.

The next morning, Melville is questioned by French television about what caused the blaze. Standing in front of his ruined studios, Melville makes no secret of his surprise, not to say suspicions:

Jean-Pierre Melville: The fire started in the soundproofed, double-walled ceiling, where there are absolutely no electrical wires, so it can’t be a short circuit.

Reporter: Was it set deliberately?

Jean-Pierre Melville: (wagging his head) Umm, it’s a possibility. In any case it would tie in with a whole lot of things that have been happening in the last six weeks relating to the studio, and it shouldn’t be discarded out of hand.

Reporter: You have one of the few movie studios in Paris where shooting goes on full-time?

Jean-Pierre Melville: Well, right now there’s a big crisis among the studios. I’m not accusing any of my colleagues who are proprietors, but at the moment I am the only one whose studio is in production—and I was expecting it to remain in production for quite some time as I have several films to make—so, I wasn’t a customer for the other studios. In the last six weeks there have been all sorts of annoyances, inspections, people who showed up, there was pressure put on my producers, intimidation not to shoot here. It’s all just a coincidence; I’m somewhat on edge because of it all.

Demobilized after the war, he’d had to scheme, shoot without a permit, without money, and he’d been marked as an outsider, an amateur on the fringes of a centralized, unionized French film industry. He built his own movie studio in 1950 in the heart of the 13th arrondissement and installed living quarters above it, a dream situation and a nightmare.

From reading Melville’s interviews, it appears that the intention to build his own movie studio was a founding moment. Enlisted with the Free French Forces, Corporal Melville took part in the Allied invasion of Italy and the famous battle of Monte Cassino, under the command of General Juin. Monte Cassino, the last obstacle between the Allies and Rome, took five months to capture, from January to May 1944. The Allies suffered heavy losses, and during the last assault, under fire from the enemy, Jean-Pierre Melville made an oath, laying the first imaginary stone in the construction of Studio Jenner: “It was on the night of May 10 to 11, 1944, that I decided I would have a film studio. I was on the banks of the Garigliano River, the assault was starting, a deadly display of fireworks that continued into the early hours of the morning. I had the feeling, really, that the war would end. That night for the first time since the war’s start, I found myself making projects for the future. Suddenly I said to myself, ‘OK, maybe I won’t be killed, maybe the war will end tonight, as I believe, and the first thing I’ll do when I get back to Paris is look for a place to build a film studio.’ […].” The promise made at Monte Cassino, where Melville, a bit player in the vast theater of operations, crossed his Rubicon at the Garigliano River, would resolve in the great fire, the flown memories, the torched sets, and the twenty-two screenplays that went up in flames, according to legend, in the conflagration on the rue Jenner. “You have to be completely crazy to own your own film studio,” he’d said, but he would never betray his Italian promise. The shooting of The Samurai with Alain Delon was finished in a new location, the Studios de Saint-Maurice, and the facility on the rue Jenner was rebuilt year by year, until Army of Shadows was finally shot there.

And his name? It’s interesting to note that the first French translations of Herman Melville were undertaken in the prewar years by two giants of French literature: Pierre; or, The Ambiguities, by Pierre Leyris, and Moby-Dick by Jean Giono. If we were to delve further into Jean-Pierre Melville’s epoch and approach his bedside table, we would surely find on it a book that explained his pseudonym “Melville,” namely, Pierre; or, The Amibiguities. While not wanting to lose our way in literary quarrels, it’s worth noticing that Herman’s opus brought writer-translators bobbing in its wake just as the whale attracted Ahab: Leyris and Giono, but also Cesare Pavese in Italy. Each time, posterity has debated the translation, some praising the artists’ transpositions as offering the closest possible correspondence, while others, more querulous, the nitpickers and unbending scholars, point to the infidelities, characterizing them as errors and betrayals. Not long ago, in Italy, I heard the same refrain from an editor friend, as he plucked from his bookcase a first edition of the Italian translation of Herman Melville’s masterwork, Moby Dick o la balena, published by Frassinelli and translated by Pavese in 1932. A northern Italian intellectual to a T, my Milanese friend carries an elegance our decadent age has ushered out of fashion, a character from a Nanni Moretti film, and talks about literature while the world crumbles around him with the firm conviction that his seemingly futile words protect the edifice from collapse at its foundations, cracked though they may be. His copy of the first edition is superb, azure blue, a crude line drawing of a whale splashed on the cover, and a spout of water rising above it like a palm tree against the canvas of the sea. It reminds me of Rockwell Kent’s lithographs in the Random House edition of Moby Dick.

In France, Jean Giono seized on the whale with the ambition of “trying to recreate the depths, the chasms, the abysses and the peaks, the tumbled rockfall, the forests, the dark valleys, the cliffs, and the heavy confection of the mortar of it all.” It was an unusual translation, the collaboration of three people, initiated by Gaston Gallimard. Giono asked an English friend unrelated to the world of letters, an antiques dealer in Saint-Paul de Vence, if she would write a literal, interlinear translation of Moby-Dick that would convey the book’s meaning word for word. For the next stage, the author assigned his old friend Lucien Jacques to transform the raw material into a fluent translation. Meanwhile, Giono would undertake a parallel effort to rewrite Moby-Dick from the crude first draft. He explained his method to Lucien Jacques in a letter: “Asking Joan Smith to make us a word-for-word that you and I will each work up separately into our own versions so that at the end we can compare our texts and combine them into one.” Little by little, in bundles of 100 pages, Lucien transformed “into sentences as well-constructed as possible the spineless text (strictly word for word) that Joan sent him.” As a final coat of paint, Jean Giono would rewrite it, stopping at the more perilous passages to cast an eye back on the original.

The back-and-forth over 1938–39 produced a writer’s translation, a faithful betrayal in which the two universes correspond in such a way as to feed off each other without either swallowing the other. As Giono wrote, “This book has been my foreign companion. When, as so often, I would stop to contemplate these large empty spaces, undulating like the sea but immobile, I had only to sit with my back against the trunk of a pine, pull this already rippling, lapping book from my pocket to feel the varied life of the ocean billowing up from below and extending all around me .” [4] Unable to leave the ship straight off, Giono immerses himself in writing a preface for this three-headed translation, the dream life of Herman Melville, a study in admiration, fantastical imaginings in the form of bibliographical indexes, using several of the pages as the basis for a novel, Pour Saluer Melville [A Salute to Melville]. He gathers a few biographical snippets to which he annexes dreams of his own, and Herman Melville becomes the narrator of an intimate personal story, announcing that “something extraordinary is going to happen to him if he isn’t careful,” not specifying whether the warning applies to himself or to his character. All this transpired during the Phoney War, when the army had been mobilized but was staying behind its defenses. Giono, a militant pacifist and the author of Déserteur [Deserter], was imprisoned at Fort Saint-Jean in Marseille. A Salute to Melville, his “prison book,” was written in three months, from November 16, 1939, to March 1, 1940, and published on his release.

We don’t know whether Grumbach, who would later become Melville, owned Moby-Dick in translation or in the original, whether as an admirer of the American author he seized on the “life of Melville” written in prison by Giono or ignored it altogether. What we do know is that he read Herman Melville and considered Pierre; or, The Ambiguities a masterpiece, to the point that he adopted the novelist’s patronym for his own. But let us look at just how Jean-Pierre Grumbach came to blot out his own story in favor of a myth and trade Alsatian assonance for Anglo-Saxon consonance. For that we need to push further back into his war years, return to his beginnings, follow him to Paris, then Dunkirk, Castres, Marseille, Barcelona, and London, travel France’s roads and listen to him tell of his feats of arms, discover in the horror of the Italian campaign the feel of dying days, discover in the morning dews the renewal of precarious fortune: “I hesitated a long time before taking a name. It happened during the war, mine is a difficult name to pronounce, an Alsatian name, Grumbach. Not that I don’t like the name, but even back then I was terribly drawn to Anglo-Saxon consonances, and as the three gods of my childhood were Jack London, of course, then Poe, and much later Melville, just before the war in ’39. I’d been wanting to adopt the name of someone I admired, and Herman Melville struck me—and still does strike me—as one of the greatest writers in the world.”

Before he joined the Free French Forces in London and took a new name the way another might take the cloth, Jean-Pierre Melville lived as Grumbach, a Jewish name from Alsace that is pronounced with a harshly aspirated final consonant. He would publicly reclaim his heritage later, just as he systematically erased it during the war. It was a victim’s name that needed to be replaced by a nom de guerre, a codename, a falsehood. “If my name had not been Jean-Pierre Grumbach, I might have become Lacombe Lucien,” he liked to say, by way of painting in a gray wash the Manichean worldview of postwar France, which pitted collaborator against resistance fighter. Lacombe Lucien, the creature of Louis Malle’s camera and Patrick Modiano’s pen, sides with the Gestapo in Vichy France more from happenstance than by choice. Melville makes the point that had he not been the targeted victim, he might have become his own executioner. Bad side, good side, good choice, bad choice, we’ll come back to it.

The son of left-wing, progressive parents, he grew up in the shadow of his brother, Jacques Grumbach, a reporter for the Socialist daily Le Populaire and a prominent member of the S.F.I.O., then he served on the General Council of the department of Aube in northeastern France. Jean-Pierre, his baccalaureate in hand, abandoned his studies and, unlike his diploma-ed older brother, bounced from job to job, working as a broker for Vanderheym and as a salesman at Lang, a toy manufacturing company. The pertinent image from these years is of a jovial young man who takes a handsome photograph. As a child, he’d had an adult’s face, the dark-suited Melville already there, lurking in an expression, a look, a smile. If he ever were to enlist in a quest, he would submerge himself in it: “Of all the magnificent projects I envisaged for myself, nothing remains. I’d like to come face to face with a great danger and finally stop doubting myself,” Melville wrote his brother. The call of the void is something that Jean-Pierre shared with his distant and adoptive ancestor Herman. The raccoon rings around his eyes would carve his flesh into a mask, deep purplish gray runnels under his bulging eyes that only his dark glasses would ever wed. The cheeks, the neck would grow chubby and protrude from his face, a face he would fall flat on, taking pleasure in it. The suit accompanied him on his shambling descent, both a cornerstone and an implacable barrier against the world: “I wear this hat because it suits me better than any other, because I’m fat.”

Olivier Bohler, who directed the documentary Code-Name Melville, a judicious collage of film extracts, interviews with colleagues and acquaintances, and readings from unpublished archives, presents the history of the man behind the camera and lifts the veil from the shadowy origins of the work. Casting his nets, Bohler hauls in a miraculous catch. He manages to put his hands on the classified document recording the interrogation by the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action (the central bureau for information and action, or BCRA) of young Grumbach before it accepted him into the Free French Forces. Exhumed from the Centre Historique des Archives de la Résistance in Vincennes, the record preserves the voice of soldier Grumbach, who after the fall of France turns into “Nano,” then “Cartier,” before assuming the imposing aspect of “Melville,” which he would retain ever after. A complete account of his early war years, from enlisting in the French army to joining the Resistance, from the soldiers crowding into Dunkirk, to the first crossing of the English Channel with defeated and bewildered infantrymen, to the wandering course of his exodus in France until he managed to cross the Pyrenees and sign up with the Resistance in London, it is the deposition of a young man’s career through history.

In October 1937, Jean-Pierre Grumbach starts his military service. He volunteers for the 71st Artillery Regiment in Fontainebleau, is seconded to the 1st Auto Inspection Unit, proceeds to the front in September 1939, and relates in his London interview his different postings, the fall of France, and his demobilization. “I spent the winter in HEUDICOURT in the Somme, in SAINT MARTIN-RIVIERE and VENEROLLES in the department of Aisne. On May 10, I went up to the front, and we campaigned in FLANDERS. I boarded ship in DUNKIRK and spent six days in BOURNEMOUTH. On June 9, I returned to BREST. From there we proceeded to EVREUX. We had three guns, which we were obliged to abandon under orders. Finally, we withdrew to CASTRES, arriving there exactly on June 24, the evening of the armistice. We were billeted near MAZAMET. I was demobilized on August 10, 1940,” he recounts. From Castres he went to Marseille, where he tried in vain to find a passage to London. His first paid work dates from this period. Hired as a salesman for the Société de Couture et de Confection, Melville uses his frequent work trips in the south of France as cover for distributing newspapers and propaganda tracts for the Resistance in the Free Zone: “The S.C.C. had nine salesmen for the Free Zone, and I often traveled to the TOULOUSE region. I worked in this capacity for a year, and I left MARSEILLE in January, 1942.” He moves to Castres, where he works for the organization Combat et Libération and becomes an agent for BCRA, responsible among other things for transporting radio transmitters and preparing landing strips and parachute jump sites.

Starting on November 11 when the German Army assumed control of the Free Zone, Grumbach, alias Cartier, decided to try reaching London by escaping over the Pyrenees. The only way was to put his fate in the hands of a passeur on the dangerous mountain trails that so many Resistance fighters, Jews, and Allied military personnel had taken before him, escape lines across the heights that separate France and Spain. The combatant’s road, where Walter Benjamin died. Grumbach tells the story of his own passage: “Right at the start, there was a little incident. We reached LUCHON and were to meet Dr. TAILLADE that evening in a hotel whose name I forget. I was still with SCHMOLL and Mrs. REY BARAGE, who had joined us. This was on the night of November 13. TAILLADE arrived around midnight, completely drunk. He told me: “OK, I’ve met the guy, it’s perfectly simple, he wants 30,000 francs from us, and there’ll be a taxi to drive us into BARCELONA.” I included SCHMOLL in the deal. There was a third person with us, a kid we’d met in TOULOUSE and wanted to bring along. His name was BERCOVIC, he worked as a steward in a shipping company, strong build, spoke many languages, a Frenchman, military decorations, a nice enough kid. When he saw TAILLADE, he decided not to join us, because he didn’t feel the guy was straight, and he told us he was sure that TAILLADE had arranged things with our guide so that he wouldn’t pay anything at all. The next day, we had a pretty stormy confrontation with TAILLADE. He introduced us to François LADRIX, who assured us again that as soon as we crossed the border, we would find a taxi that would take us to the door of the British consulate in BARCELONA, with a police captain in the seat next to our driver. SCHMOLL and I decided that it was worth the risk, and we agreed to meet the Spanish guide who would smuggle us across that very night. We also agreed to make a first payment of 15,000 francs and to give the remaining 15,000 francs once we reached BARCELONA. François LADRIX accepted these terms, and SCHMOLL and I each paid our 15,000 francs. TAILLADE put up no money and afterward told us that he had already paid.

“The three of us left on the morning of November 14, heading toward the Spanish Notch, where we crossed the border. We spent four days and four nights in the mountains, where we climbed the Maladeta Range. In all, we crossed four mountain ranges; luckily, there wasn’t much snow at the time. In all, there were four guides, and we were twenty in our caravan. There were women, children, and two Belgian couples. Of the sixteen passengers among us, four had not paid. The LADRIX brothers did not take payment from single men who were going off to fight; we’d had to pay because of Dr. TAILLADE, who had announced that we had lots of money and could also pay for him. Jean LADRIX told us this while we were in the mountains. We climbed to a perfectly round lake surrounded by snow, at 3,200 meters exactly, Del Mar Pond, I believe, in the Maladeta Range. The French guides did not know the path, and the Spanish guides made us traipse all over the mountain, saying it was to avoid the carabinieri. The Spanish headman was called CAMPANETA, and he would appear from time to time out of the mountains. We passed through VIELA and finally, at 6 a.m. on November 19, we arrived at VILLALLER, where we were to find the famous taxi that would bring us to BARCELONA (VILLALLER is in Aragonia). We arrived in BARCELONA that night without incident and presented ourselves at the British consulate. I had two sets of identification papers on me, a real one under the name GRUMBACH and a fake under the name CARTIER. I submitted the real one of course, and the consular secretary, a wonderful old man, Mr. WHITFIELD, took us to a clandestine boarding house, where we spent two weeks.

“At the boarding house, I met two young Jews from Belgium who knew me by sight from MARSEILLE. The first thing they said to me was: “I hope you didn’t declare yourself a Jew at the British consulate.” I said that no one had asked me but I fully planned to. They said: “Don’t, on any account! There’s an organization that smuggles people out, but not Jews.” I believed them in the end, they spoke with such sincerity. The next morning, I returned to the consulate with SCHMOLL, who advised me to take back my real identification papers and leave the fake. We went into Miss STOCKLEY’s office, and while SCHMOLL chatted with her I was able to retrieve my real identification papers, and I replaced it with the fake ones under the name CARTIER. We signed our enlistment forms, SCHMOLL putting his religion as Catholic, and I did the same.”

In early December, Jean-Pierre Grumbach joined a first convoy for London via Gibraltar. In the middle of the night, his ship was boarded and inspected in the port of Barcelona, and the entire crew was confined to the hold while the Spanish police carried out its investigation, from December 4 to January 25, 1943: “First the Spaniards thought we were spies, then commandos. They’d found a list on the boat of all our names. They called the roll, and as we didn’t understand what was going on, we answered when our names were called.” He was to spend time in Spanish jails, first in a ship’s hold, then in the military prison in Cartagena from January 24 until May 31, 1943. Cleared by the investigation, Jean-Pierre boarded the London-bound Samaria in Gibraltar with eighty other Frenchmen. On July 24, the Samaria docked in Liverpool. Jean-Pierre spent seventeen days in Camberwell, then four days at Patriotic School. There he met a good friend of his brother’s, a hero of the Resistance, Pierre Brossolette, and also Captain Bloch. It was thus that in 1943, crossing the channel as if the Acheron, led by a steersman in the guise of a passeur, via Spain and the holds of uncertain ships, the Resistance fighter Cartier, alias Nano, became Melville. As the interview record concludes: “Volunteer GRUMBACH produced a very good impression. From the State Department’s perspective, there is nothing to hinder his induction into the Free French Forces. He has been issued a No. 1 Visa.” A birth, brought about by the power of the word: “Call me Melville.”

The Resistance movement within France, the Italian campaign, and the liberation of France from German occupation marked Melville indelibly. There is not a film of his where, hidden in the features of a gangster, woven into the solitude of a hired gun, or even buried in the uncertainty of a high-rolling gambler at the gaming table, the bitter years of combat are not present. Melville in his second stage carries, in the lining of his suit, on the inner surface of his Ray-Bans, an obsession with a frightening but also incredibly happy period.

Preserved in Melville’s archives at the home of his nephew Rémy Grumbach is a scouting notebook where the force of these memories is underlined in red pen. On one of the large pages, two juxtaposed photographs provide a troubling insight into Jean-Pierre Melville’s monomania about the war. On the left, the famous photo of Jean Moulin taken by Marcel Bernard during the winter of 1939 in the Arceaux district of Montpellier, against a Roman aqueduct in the Gardens of Peyroux. Jean Moulin, future commander of the Resistance, unifier of its many clandestine networks, wears a scarf around his neck and a fedora pulled down over his eyes. On the right, same pose, same place, leaning against the same stone, Jean-Pierre Melville in a dark suit, white shirt, and black necktie, with a fedora pulled down over his eyes, mimics the attitude of his elder, the glorious martyr of the Resistance. Two red lines at neck height on Jean Moulin, at shoulder height on Jean-Pierre Melville. Written below the two side-by-side prints, “same relation as the other,” and a line measuring the field of vision, “80.” A strange notation, which reveals a pathological dimension when the tracing paper protecting the photographs is lowered in place.

The title of this arrangement, written in red felt-tipped pen, is “A la recherché de Jean Moulin” [In Search of Jean Moulin], and, at chest-height over the Resistance hero, “the firehouse in Melville (Long Island, New York).” The mention of this little town in Suffolk County, New York, seems to come out of the blue, beside these images of a Resistance fighter and his mimic under classical arches in the south of France. It would be idiotic to dismiss these oddities with a careless wave of the hand, as the reference to the town of Melville seems an important key to understanding this two-part man who was reinvented by a baptism at sea. Jean-Pierre Melville seems to take pleasure in his double identity and to confirm the validity of his choice by braiding together the elements of correspondence, seeking validation for his patronym in the name of a town. Melville, near New York City; a firehouse, like the one where Sinatra’s father worked in Hoboken; and, later, a scene from L’aîné des Ferchaux [Magnet of Doom] is weirdly and gratuitously shot in Melville, Louisiana, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Odd guy, this Melville.

Ambivalence toward the pain and acuity of his precarious wartime existence is the very mantra of this double man, Grumbach the hunted Jew reborn as Melville the fighter for Free France. “As I grow older,” Melville wrote, “I see that everything that should have been bad memories, from 1940 to 1944, now belongs to a period that can only be relived in nostalgic dreams. […] I think that if I’d died and had a twin brother who could think of me as I can think of myself at that time, he wouldn’t have any regrets about me either. It was a fantastic period, one you had to live through, and I’m happy to have been twenty-two years old in 1939. It’s a special mercy that was granted me.” World War II is the setting for three of Melville’s thirteen films, a horrific backdrop that never intrudes on everyday life to the point of sweeping it up, coarsely and bombastically, in historic events. Instead, the men concerned are always at grips with an everyday situation that is magnified by outside events; they are anonymous extras who have been summoned and challenged by history, whether it’s the passive resistance in The Silence of the Sea, the rural setting and daily aspect of collaboration in Léon Morin, Priest, or again the dawn companions of the secret networks and anonymous heroes in Army of Shadows. By subtle touches, Jean-Pierre Melville transposes a portion of his story into each of his films, blends two memories into one scene, his always-implicit presence similar to Hitchcock’s cameo appearances, at the back of a bus, stepping off a train. When asked on a radio show, “Making a film, do you live other lives?” Jean-Pierre Melville answered: “You start to play a composite role when you’re an author or a director. It’s absolutely true that while I was filming Léon Morin, Priest, I really convinced myself that I was a Catholic, believing as a true mystic. And I managed to instill that in my leading actor. And that’s why you have to live several lives, you never get as much from the actors you’ve chosen if you don’t give them your own conception of the role, even if you never say it out loud, even if it’s not written in the screenplay.”

Sometimes a scene from real life is transposed to film, and the chastely evoked pain invades the frame. In Army of Shadows, Jean-Pierre Melville adds a scene from his life in the Resistance to Joseph Kessel’s novel, a bit of dialogue between Luc Jardie, played by Paul Meurisse, and Philippe Gerbier, played by Lino Ventura, as they exit a movie theater in London: “For the French, this war will be over when they can go see this film, Gone With the Wind, and read [the satirical magazine] Le Canard Enchaîné.” These words, a nose-thumb at the dark years of the Resistance, Jean-Pierre Melville had heard them himself from the great Resistance figure Pierre Brossolette in front of the Ritz Theater in London. Harmless enough on first hearing, the quotation in its cinematic setting touches on a deep and persistent source of suffering, the great tragedy in Jean-Pierre Melville’s life, the death of his older brother, Jacques Grumbach, during World War II.

On the rue de la Roquette in Paris’s 11th arrondissement, exactly across from the synagogue attacked during the pro-Palestinian demonstrations in July 2014, not far from the theater where the comedian Dieudonné, conspiracy theorist and sorcerer’s apprentice of a new anti-Semitism, has held court, and a few streets from La Belle Equipe, the corner bar on rue Charonne that was sprayed with bullets on a warm autumn evening by the coordinated fury of a murderous madness we have not yet measured to its full extent, lives Rémy Grumbach, son of Jacques, nephew of Jean-Pierre, now a sixty-something former television producer, and the director of SACEM, Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique. At first glance, Rémy’s resemblance to his uncle is slight, but two snapshots on the bookcase play on the relationship. In one, Rémy holds a Siamese cat up to the lens, hiding part of his face, mimicking the pose taken by Jean-Pierre and Amok in another photograph. The bookshelves in his apartment are crammed with crime novels, most of them from the Série Noire collection published by Gallimard. It feels like familiar territory.

From the outset Rémy’s soft, amused voice creates an atmosphere conducive to exchanging confidences. He tells me that before my arrival he sorted through his filmmaker uncle’s archive. The photographs, notebooks, pages of handwritten notes are gathered in a suitcase on the patio table. I insist that the story of his father, Jacques, the other Grumbach, interests me, his career in journalism and politics, but also his actions during the war and his tragic death in 1942. A framed portrait of his father stands on a sideboard to the right of the entryway: Jacques Grumbach, a slightly puffy face and a professor’s round eyeglasses, his suit worn over a V-neck sweater, a striped necktie. A militant socialist in the prewar years, founder of Socialist youth groups, Jacques Grumbach was one of the leading men of the French Section of the Workers’ International, or SFIO. and a close associate of leftist Prime Minister Léon Blum. During the years of the Popular Front government, Jacques Grumbach pushed his militant agenda in the newspapers, first as editor in chief of Révolte, in partnership with Paul Favier, before joining the ranks of Populaire, the media mouthpiece of the Front Populaire party, where he met his other great friend, Pierre Brossolette. His forceful opinions at the time of the Munich Agreement, his editorials denouncing the growing threat of Hitler’s politics, earned him a spot on Nazi Germany’s blacklist of French politicians and journalists. Unfit for active service because of near-sightedness and a weak heart, “when the war started, he was excused from military duty because of a cardiac condition related to cyanosis. But he moved heaven and earth to get enlisted. I still have a photograph of him as a soldier. This man who was goodness itself was literally in disguise, he tried with all his heart to hate the enemy. It would have been grotesque, had it not also been sublime!” a friend wrote in an elegy.

Demobilized after France’s defeat, Jacques Grumbach joined the Resistance in the south of France. He helped found the underground Le Populaire clandestin with Daniel Meyer in Marseille, where he also renewed ties with his brother who was then shuttling between that city and Castres. In November 1942, he tried to get to London by crossing the Pyrenees into Spain, carrying a large sum of money earmarked for the Resistance. He found a passeur and joined a convoy going to Andorra via the Montcalm Peak in the Ariège. The group was still on the trail when night fell, and Jacques, whose foot was injured, lagged behind the others. He was never found, the passeur who went back for him returned alone, suggesting that Jacques had turned back. He was reported as missing on November 25, 1942. On his arrival in Spain, Jean-Pierre Grumbach learned that his brother had died of a heart attack while trying to cross the border.

Still, all hope was not abandoned, it’s possible he became a prisoner in Germany, it’s possible he’s in a camp, he’ll return, let’s keep our faith. Rémy says, “All I can tell you about my father consists of a few actual memories, plus what was told to me about my father and what I have been able to piece together from these secondhand memories. I remember very clearly being on my father’s bike, I was two and a half years old. I have vivid memories of the bike rides we took in Gémenos, near Marseille, where my grandmother had a house. I remember going to the restaurant with my father, I even remember what I ate, canned sardines, across from the Provençal building, and going to the Odéon Theater in Marseille, to watch a play with Charles Trenet. A fourth memory, in Castres, I’m seeing him for the last time, he hugs me before he goes; there were bicycle taxis, he took me with him and then he wanted to accompany me home again, we went as far as the station. He couldn’t leave me, he came back to the house, then set out a second time. Other than these four memories, I remember having waited for my father, all through childhood I waited for my father, like a dog who loves his master. It’s horrible when a dog is neglected, you see it in its eyes … I waited for my father the whole time, I was convinced that he was coming home. I waited, I wasn’t desperate about it, I knew he was alive, knew he would return. From time to time I would say, ‘Oh, that’s him coming.’ At first I was told that he wasn’t dead, that he’d most likely been made a German prisoner, that he’d surely been sent to a concentration camp, that they were looking for his name in the list of returned prisoners; since he didn’t appear in the lists, he had probably been freed by the Russians and not the Americans, which complicated things. Then I was informed of his death.”

Eight years after Jacques Grumbach disappeared, in September 1950, during an aerial survey of the Ariège section of the Pyrenees, a body with its skull pierced by a bullet was found in a ravine high above the Siguer Valley. The cadaver was retrieved by caravan and brought to the village of Gestiès on September 27, 1950, where it was buried. Initially the body was thought to belong to an English officer, a Sir Davington-Dell, who disappeared in October 1943. After a lengthy investigation, the authorities determined that the body was Jacques Grumbach’s, formally identified by his widow and Jean-Pierre Melville. A surgical scar for mastoiditis on the right-hand side clinched the identification.

The dark hours of history are engines for generating improbable fictions, and this resurgence of the past is no exception. On December 30, 1950, the passeur Cabrero Montclus was arrested and confessed to murdering Jacques Grumbach. At the Ariège courthouse, he explained that he had acted so as not to endanger the rest of the convoy. Overcome with exhaustion, Jacques Grumbach had to be left behind, and he could have betrayed his companions. “I acted on orders, I killed M. Grumbach to save the others,” said the passeur. However, he was unable to explain the disappearance of 7,000 francs from the knapsack Jacques Grumbach was carrying, though he claimed without proof that the money was subsequently given to his bosses. The corpse robber was acquitted by the Ariège Court, the jury considering that it was impossible to judge his actions with certainty.

Jean-Pierre Melville made no objection to the court’s decision, on the grounds that Montclus had saved the lives of others while traveling back and forth to Spain. Showing magnanimity, Jean-Pierre absolved his brother’s killer, to his nephew’s regret. “I’m starting to understand the trial and Jean-Pierre’s ambiguous position,” says Rémy. “In his way of thinking, you can’t be a bastard at the age of seventeen, the boy just made a bad choice. … I don’t agree at all, but I’m starting to understand Jean-Pierre. Having the same heart problems as his brother, he thought Jacques had had a heart attack. Or he just forgave the guide; he thought it wasn’t about the money. But he was wrong. Many years later, I received a phone call from Biarritz, it was Cabrero, the passeur, he wanted to talk to me. He was determined to apologize, he confessed to me over the phone: ‘I’m going to return all the dough I took.’ He’d even calculated the conversion rate from the francs of that era, it was ridiculous, and he added, ‘Even if it means nothing anymore, I want to give it back before I die.’ I refused to see him. And that’s my father’s story,” Rémy finished. Then we strolled out to lunch together, heading for the restaurant Chez Paul, on the rue de Charonne, where Rémy relished a plate of tête de veau. He pointed out the cops surveilling the rue Keller, guarding the apartment of Prime Minister Manuel Valls. A state of siege reigns in the streets of the 11th arrondissement, carefreeness has been replaced by constant suspicion, and how is one to believe that history is not repeating itself, different only in its inventiveness when it comes to horror?

Rémy returns to the subject of his father, “I then discovered my father by wanting to learn more about him. I went to the offices of Populaire, visited the director of Provençal. A number of his friends had been deported, some were dead. I even remember Vincent Auriol inviting me to the Élysée Palace, he’d asked to see me, maybe twice over the course of ten years. I started to realize my father’s importance in the world of politics. You see, he was a truly good man. I’ll tell you an amazing story. Ten years ago, I get a call from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, from Dominique de Villepin’s office, I think: ‘Hello, Monsieur Grumbach, the television producer?’ Yes? ‘I believe you’re the son of Jacques Grumbach?’ Yes. ‘Could you come to the ministry, we have something for you, we have a file that we would like to give you relating to your father.’ I go there and they give me a fat file in a box, wrapped in brown paper, it says TOP SECRET. The man told me that the file had been seized by the Nazis, then by the Soviets. The documents were annotated in German and carried Soviet stamps. Then the whole thing had been sealed by the ministry, labeled EYES ONLY, and kept in storage for ten, fifteen years. It was a packet of perfectly normal letters, but reading them you realized that, behind the various requests, something else was always being asked. They would be letters from constituents to the councilor of the Aube, saying, ‘I’d like to open a butcher shop blah, blah, blah’ and then, without any emphasis, ‘I’d like my brother to join me, he’s coming from Poland. Would it be possible to get him here quickly?’ Before the war, my father had set up a network to exfiltrate people from Germany, Poland, etc. He was quite a man.”

Jean-Pierre’s attitude toward his brother’s murderer highlights the man’s deepest ambiguity. Unexpected, unclassifiable, quick to take a side step, he is forever turning on its head the commonplace and the simplistic. With his brother a committed Socialist, he became a right-wing anarchist and took pleasure, in the conformist setting of his cultural milieu, in expressing his devotion to the army and its representatives. And while the French New Wave filmmakers hailed him as a founding figure, he opposed their moral transgression from his seat on the board of censors, where he categorically banned all pornography from film, defining it in the strictest terms. Melville always turned up with a series of sharp, shocking, and amoral pronouncements, which he dispensed in his affected voice, enunciating each word with gracious geniality:

Reporter: Do you bear any resentment toward your adversaries during the war?

Jean-Pierre Melville: Absolutely not!

Reporter: You’re not a vengeful person?

Jean-Pierre Melville: No, not in the slightest! Some of my friends were in the SS once!

Reporter: What sort of relations do you have with them?

Jean-Pierre Melville: Excellent, warm and cordial.

Reporter: How do you explain that? Big-heartedness, empathetic understanding?

Jean-Pierre Melville: No, I don’t know, I don’t try to explain it at all. And yet I think I can explain it. I like people who take part in things, who—and I apologize for the common expression—wet their oar, who do things. And I believe that people who have risked their lives for a bad cause or a good cause are interesting people. I don’t much like people who stay neutral.

War changed Jean-Pierre Grumbach into Melville, basically took from him even his birth name, his innocence, confirming him blocklike under his patronym, a solid character with a studied set of accoutrements, an impassable mask. The fighting, the atrocities, painted his reality gray, erased the idiotic border between good and evil, set him down firmly in a world of nuance where the bad man is never entirely bad and the good man is never entirely good, a world peopled with nice bad men and bad nice men, humans who are all too human. “I would like to make a war movie, but I can’t talk about what I saw during the war,” he explained. “My movie would be censored and would never be distributed. I’d have to make one based on a screenplay, a novel, something ‘invented,’ because I could never tell all the little stories, the things I saw. […] War is waged against the enemy, of course, but it also has an existence within one’s own ranks. It’s this kind of internal war that I’d like to address in a book. I’ll give you one or two examples. On August 18, 1944, in the outskirts of Toulon, five Germans came out of the woods with their hands in the air, walking toward our 13.3, a small, lightweight tank. They wanted to surrender, I’m the only witness, which is a problem. The tank’s hatch opened and a noncom stuck his head out and motioned to the Germans to approach. A little too late, I sensed what was going to happen. I was about to shout to the Germans when the tank sped up and ran them over. Like a jerk, I unholstered my revolver, and the noncom shut the turret and swiveled the machine gun toward me. That’s a nice war scene, right?” If Melville were to write this war with its thousand facets, obviously sordid, would he wear the suit of the novelist Parvulesco that he played in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, the man whose “greatest ambition in life” was “to become immortal and then die”? “I am perhaps a little more ambiguous in my cinematic intent than Melville was in his literary attitude. I am not entirely sure that the good is always white and that black is on the side of evil. I’m unsure whether Ahab isn’t as much at fault as the whale. He’s proud. On the margins of society are the victims. Israel Potter is a victim, Billy Budd is a victim. Herman Melville’s most accomplished book, and the one I reread with wonder each time, is Pierre; or The Ambiguities. An absolutely fantastic work.”

Adrien Bosc is the winner of the Grand Prix de l’Acadamié Française for his first novel, Constellation, which will be published in English in May. He is also deputy editor at Le Seuil and a founder of Éditions du Sous-Sol.