How Do You Say Turkey in Yiddish?

Rokhl’s Golden City: Why Yiddish culture, alive and well, needs small but reliable financial support, not saving

I went to a Yiddish lecture this Sunday. That’s not news. The Sholem Aleichem Cultural Center on Bainbridge Avenue, Bronx, hosts monthly Yiddish-language programming, and I try to make it up there as often as possible. This summer I saw Naomi Seidman speak about the image of Jesus in Yiddish literature, a talk that was just as delightful as it sounds. This Sunday, though, was something much more personally meaningful, no offense to Jesus. Karolina Szymaniak had come from Warsaw to speak about a hero of mine, Warsaw Ghetto chronicler Rokhl Oyerbakh.

Before the war, Oyerbakh, a formidable public intellectual and proto-feminist, was romantically involved with the Yiddish poet Itsik Manger. The relationship between Oyerbakh and Manger was a difficult one, mostly because Manger was a volatile, violent drunk. As Szymaniak got to the uncomfortable details of their relationship (something I’ve never heard spoken of frankly in a public setting) the 5-year-old playing games on his iPad behind me became restive. Yes, Manger beat Oyerbakh. He was a difficult—at which point the boy behind me suddenly yelled, in Yiddish, “Manger! I know him!”

Friends, I laugh-glared, because obviously. How blessed we are to have the youngest generation of Yiddishists with us on afternoons like this. How disgusted I am with Manger, a poet I adore. How thankful I am to Szymaniak and her groundbreaking work on Oyerbakh, a woman who suffered not only unimaginable catastrophe but also the utterly prosaic abuse of a man who claimed to love her. How absolutely, exquisitely timely.

The Bronx has long been a site of Yiddish life, and art and the Sholem Aleichem Center (and its one-time school) nurtured American-born Yiddish speakers for decades. Tsirl Waletzky, acclaimed for her papercut art, attended the Sholem Aleichem folkshul. Her son, Josh, went on to become a director, as well as an important composer of new Yiddish song. Josh has just put out a recording of six of his new compositions titled Passengers/Pasazhirn. The songs are by turn impressionistic, achingly personal and rousing, with one instant classic for the post-Occupy radical moment, Ninety-Nine/Nayn un nayntsik.

The last few years, Josh has quietly undertaken another kind of project—as a master teacher of Yiddish song. Made possible by an NYSCA grant (and the help of the indispensable Center for Traditional Music and Dance) Josh has been working with young artists interested in the Yiddish folk tradition. The work of some of my favorite artists, Benjy Fox-Rosen, Eleonore Biezunski, and Miryem Khaye Seigel, owes a debt to their intensive collaboration with Josh.

When I say that Josh’s Nayn un nayntsik is an instant classic I mean that quite literally. Daniel Kahn just covered it on his brilliant new CD, The Butcher’s Share, and it’s the kind of song that, without even trying, will righteously burn itself into your brain on first listen. The Butcher’s Share has all the things we’ve come to expect from Kahn: biting political commentary, insightful new English translations of Yiddish classics (his Shtil di Nakht gives me chills) and a rocking klez-inspired band. As much as it reflects Kahn’s own blend of Eastern Europe and Americana, The Butcher’s Share is also an expression of community. His setting of Dovid Edelshtat’s “Arbeter Froyen/Working Women” is dedicated to the late, beloved teacher Adrienne Cooper, and features vocals from her daughter, Sarah Gordon. Kahn also recorded “The Ballad of How the Jews Got to Europe,” a song from Cooper’s show Gluckel and which Cooper herself recorded on her last CD, Enchanted.

Over the years I’ve heard many well-meaning speeches by many (extremely) well-meaning people, all of whom want to “save” Yiddish. (I’ll keep this vague to spare the well-meaning guilty.) What connects these would-be saviors is that the idea of an already thriving new Yiddish culture seems utterly foreign to them. Since they themselves often don’t speak Yiddish, they assume no one else does, nor would they really want to. But Yiddish doesn’t need saving; what it needs is strategic investments, especially in people. The NYSCA grant that has supported Josh Waletzky’s work is just one example how small amounts of money can have a tremendous impact. A much larger example is Klezkanada, a yearly Yiddish arts retreat held together by a few superhuman volunteers in Montreal, a scandalously small budget, and the dedication of the thousands of students and teachers who have benefited from a yearly piece of Yiddishland.

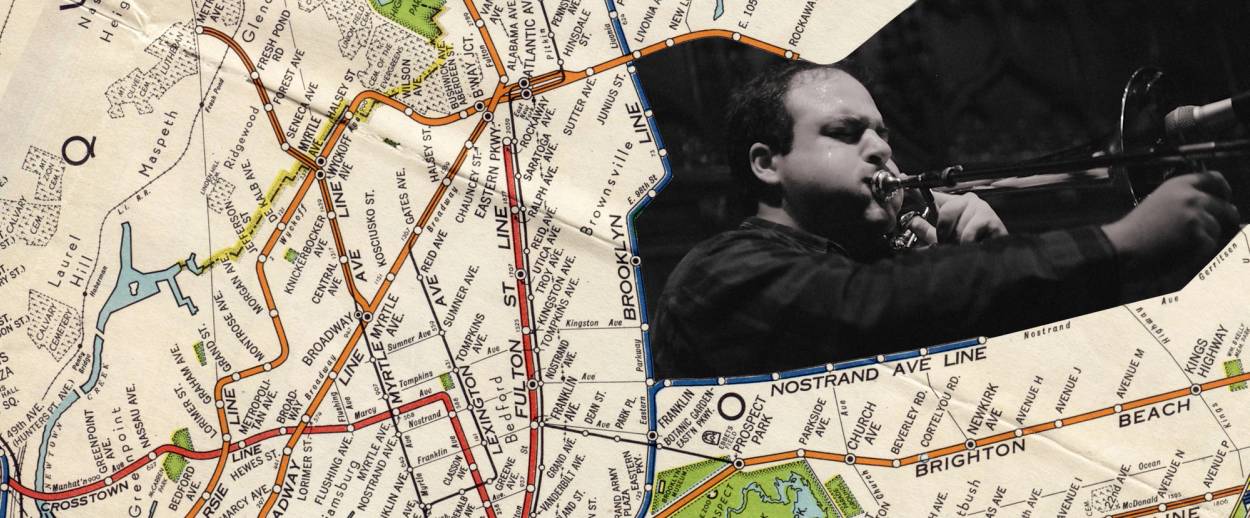

Trombonist Dan Blacksberg is as much a product of Klezkanada as he is of his alma mater, the New England Conservatory. His new CD, Radiant Others, is a funny, weird, technically ambitious, and deeply pleasurable sonic map between the two. It’s got one of the most unusual instrumentations I’ve heard on a modern klezmer recording: trombone, guitar, and keyboard. It opens with a doina (a downtempo traditional form of free improvisation) on which Blacksberg overdubbed himself five times; the only doina I’ve ever described as Prince-like.

One of the notable covers on Radiant Others is Danny Rubinstein’s “The Happy People,” one of my all-time favorite American klezmer recordings. “The Happy People” is a classic midcentury, very fast, clarinet-led bulgar meant for dancing—basically, the exact opposite of what any normal person would expect from a lead trombone. Blacksberg’s take on it is a loving, left-field homage to the music that saved us (me, and Dan, and who knows how many others) from our respective suburban cultural wastelands.

Finally, one last thankful shoutout to another Klezkanada comrade, international hip-hop star Socalled (aka Josh Dolgin). Three years ago he created the score for a new show at Montreal’s Dora Wasserman Yiddish theater at the Segal Centre. The original cast recording of Tales From Odessa is only just being released now, but it was worth the wait. And for you musical-theater nerds, Socalled’s Tales joins the Yiddish versions of Fiddler on the Roof and My Fair Lady, as well as Manger’s Megile, as one of a handful of modern musical-theater pieces completely in Yiddish.

Listen: If you’d like to know more about Rokhl Oyerbakh, click here to hear Karolina Szymaniak talk about her in Lviv (Lemberg), the city where Oyerbakh attended university.

Buy: Daniel Kahn and the Painted Bird, The Butcher’s Share, Joshua Waletzky, Passengers/Pasazhirn; Daniel Blacksberg, Radiant Others, Socalled, Tales from Odessa.

ALSO: My new fave Yevgeniy Fiks is hosting a very special event as part of his group show at the International Print Center, Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy. On Nov. 30, there will be a dramatic reading of his work, Soviet Jews in the Memoirs of African-Americans and Black Soviets. First lady of the Yiddish stage Yelena Shmulenson is taking part, in case you needed another reason to go: exhibition tour at 6 p.m., reading at 7 p.m. … If you want to immerse yourself in Yiddish literature taught by master teachers (without all the hassle of going back to grad school), New York is the place to be. For Yiddish speakers, Avraham Novershtern will be leading a rare two-day seminar on Mendele Moykher Sforim. (Dec. 2-3; contact the League for Yiddish to register.) For those more comfortable in English, Sheva Zucker will be teaching her course, World of Isaac Bashevis Singer, Mondays, Nov. 27 through Jan. 15. Register here. … Finally, Yiddish for turkey is… indik. And I’d like to wish you a wonderful Thanksgiving, and thank you for reading!

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.