Chai? Chai Not?

How Elvis showed me the way to being Jewish and different but also American and the same

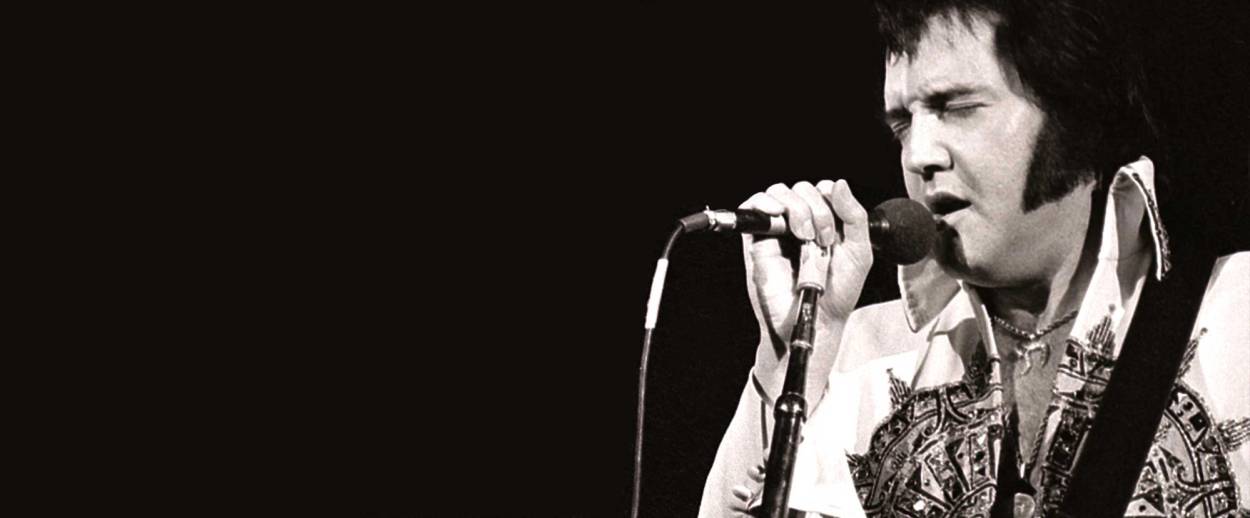

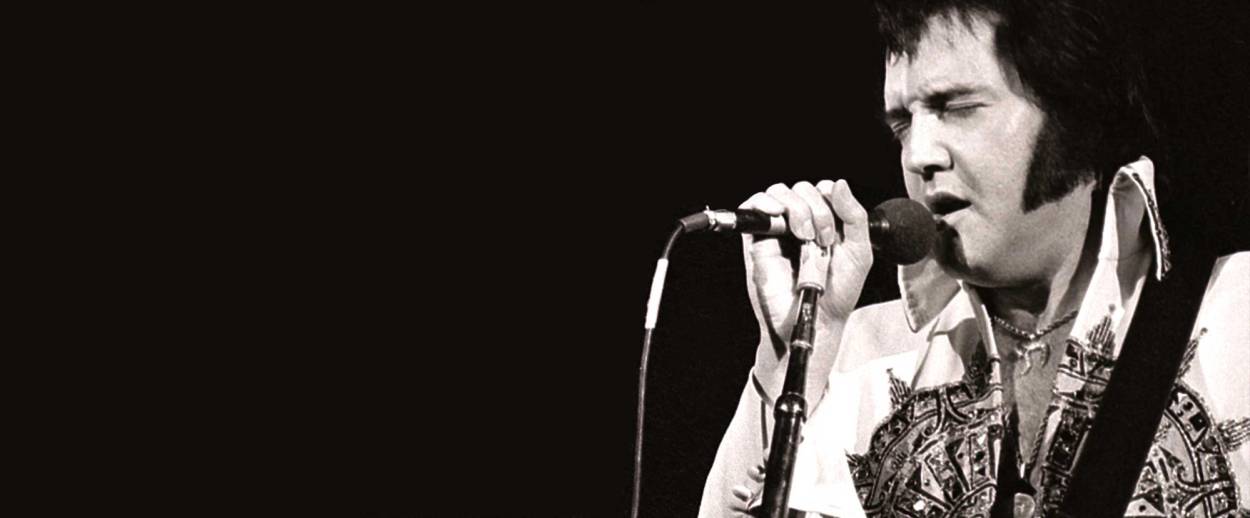

I’ve been to Graceland five times. Don’t ask why. It just happened. The last time, I’d arrived with a handful of fanatics, one of whom broke down in the King’s airplane. I noticed, as I wandered though the rope line in the living room, a Chai hanging from a gold chain in a display case amid other fancy jewelry. I was shocked. Though I knew from research that Elvis had been reading, at the time of his death, possibly on the can, The Passover Plot, the King had always seemed to me as far from Jewish as a person can get. Note the lewd dancing. Note the peanut butter and banana sandwiches. Note the love of gospel hymns, such as “If The Lord Wasn’t Walking By My Side” and “Reach Out to Jesus.” But what’s more Jewish than a 14-karat gold Chai resting in a thatch of luxuriant chest hair and catching the light?

Normally, in locations such as Graceland, I play down my ancestry, but the surprise issued from me automatically, like the ringing of a bell. I nearly shouted it. “A Chai? Elvis had a Chai?”

A docent—can you imagine a better gig?—wheeled on me. “Yes, Elvis wore the Chai,” she said, “to celebrate his Jewish heritage, but also because he approved of its message: to life!”

This encounter sent me on a long trip down the wrong trail. For years, I chased the red herring of the King’s Jewish heritage. It turns out his mom had a Jewish ancestor, or maybe it was just that the Presleys had a Jewish neighbor in Tupelo. (There’s disagreement.) It was only after many fruitless fascinating hours that I realized, instead of chasing Elvis, I should’ve been studying the Chai. The Chai! Where it comes from, what it means, and, most important, what’s the difference between those Jews who wear the Chai and those who go through the world naked as the day they were born—except, of course, for clothes.

Let’s start with a dream of the Chai, display cases filled with platinum and silver, a phantasmagoria of golden links in golden chains, winking pendants seen from across a room or perhaps magnified, each filigree of workmanship evident. A Chai consists of two Hebrew letters: Het and Yud. To the layman, these letters, taken together, look like a soccer player and the ball that player is about to head. The result is a word that means, depending on who is accosting you, either “life” or “alive,” as if each Jew wearing the Chai is marking himself as good to go. The letters have a computational value—18—which, if you’re into Kabbalah or Gematria or the witchcraft of numbers, is important. Eighteen is life, which is why, whenever I left his house for the airport, Jerry Weintraub would slip me 36 cents, saying, “Double Chai.”

Those who wear the Chai or the Star tend to be tough, self-proclaiming … men in leisure suits, with black eyes and shiny shoes, muscle Jews, shtarkers, the ones who make the more refined look away.

The Chai began turning up in jewelry a moment ago in Jewish time. 1700s, 1800s. It was only in the twentieth century that people began affixing them to chains and wearing them like medallions. For those so inclined, there is a choice: the Star of David, which is bluntly assertive, or the Chai, which is a curvy mystery. We chose the Chai for the same reason we chose Pink Floyd: because it was beautiful and we did not really know what it meant.

I began wearing a Chai in fifth grade. Not because there were lots of Jews and Chais in my school—but because there were none, which had the perverse effect of making me want to assert myself. Most of my friends were Protestants—characterized, by my parents, not as Christians but as “non-Jews”—and many of them wore crosses, always on a silver chain. You’d see it when we played shirts and skins. Crosses but also hands locked in prayer. In other words, there was a strong hint of me-too-ism in that first Chai. I wanted to be like them, have what they had, but I could not, so I had this instead. It meant I was Jewish and different, but also American and the same. I came to look down on the cross. A Chai meant life, but wearing a cross is like wearing an electric chair around your neck. If Jesus does come back, what’s the last thing he’s going to want to see?

I began to notice similarities between Jews who wear the Chai—most don’t. Those who wear the Chai or the Star tend to be tough, self-proclaiming. It’s the thick-wristed among us, men in leisure suits with black eyes and shiny shoes, muscle Jews, shtarkers, the ones who make the more refined look away. Milton Berle wore the Chai. Dustin Hoffman does not. Joe Buck, were he a Jew, would wear the Chai. Ratso Rizzo would not. I stopped wearing mine in high school—precisely because it turned out I was not that kind of Jew. I wanted to pass, be taken as one of the Memphis mafia, drinking with the boys. That is, I stopped wearing the Chai for the same reason that I’d started. Because I wanted to be like everyone else. It bothered me—that pride or lack of pride had forced me to give up a symbol of my heritage. I asked my father, because that’s where I go. He thought a moment and then began the way he always begins: “In our family,” he said, “we don’t wear jewelry. Besides, a Chai is you telling the world you are Jewish. But believe me, the world knows. You don’t need to wear a Chai; you are a Chai.”

Rich Cohen is the author of 11 books, most recentlyThe Last Pirate of New York.