The Feminist Manifesto

Reading Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, I found the urgency today’s radicals lack

A few months ago, my dad sat me down wearing a concerned look on his face and told me he didn’t think I was reading enough. He was worried I’d missed out on too many classics—not just 19th-century novels, but the scathing manifestos of brave, influential thinkers. The radicals.

We decided to form a two-person reading club, and I gave him the liberty of picking our first book. It was Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex.

I knew who she was: the early radical feminist who’d started Redstockings with my mom, Ellen Willis, then retreated from writing and activism shortly afterward. But I hadn’t read her book—or not really anyway. I had flipped through it my first semester of college, before I really cared about the concept of feminism, before I’d read Freud or Marx or any feminist theorists, before I had anything to compare it to.

As it turned out, my reread would be eerily timed—just two months before Firestone died in late August. On the surface, Firestone is what Katie Roiphe would call a “dead-serious” feminist, heeding her own call for a “smile boycott,” yet I laughed joyfully as I made my way through the book. Partly because of her wry parenthetical asides, usually in the form of archetypical 1960s refrains uttered by resigned women or unevolved men, and partly because she predicted everything from in-vitro fertilization to the super-fashionable notion of a genderless society to the mommy wars, because she pre-empted Laura Kipnis’ polemic against romantic love by 35 years, because she summed up the entirety of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth with one offhanded comment about how Cosmo and Vogue were fanning the “cultural disease” of the “search for glamour.”

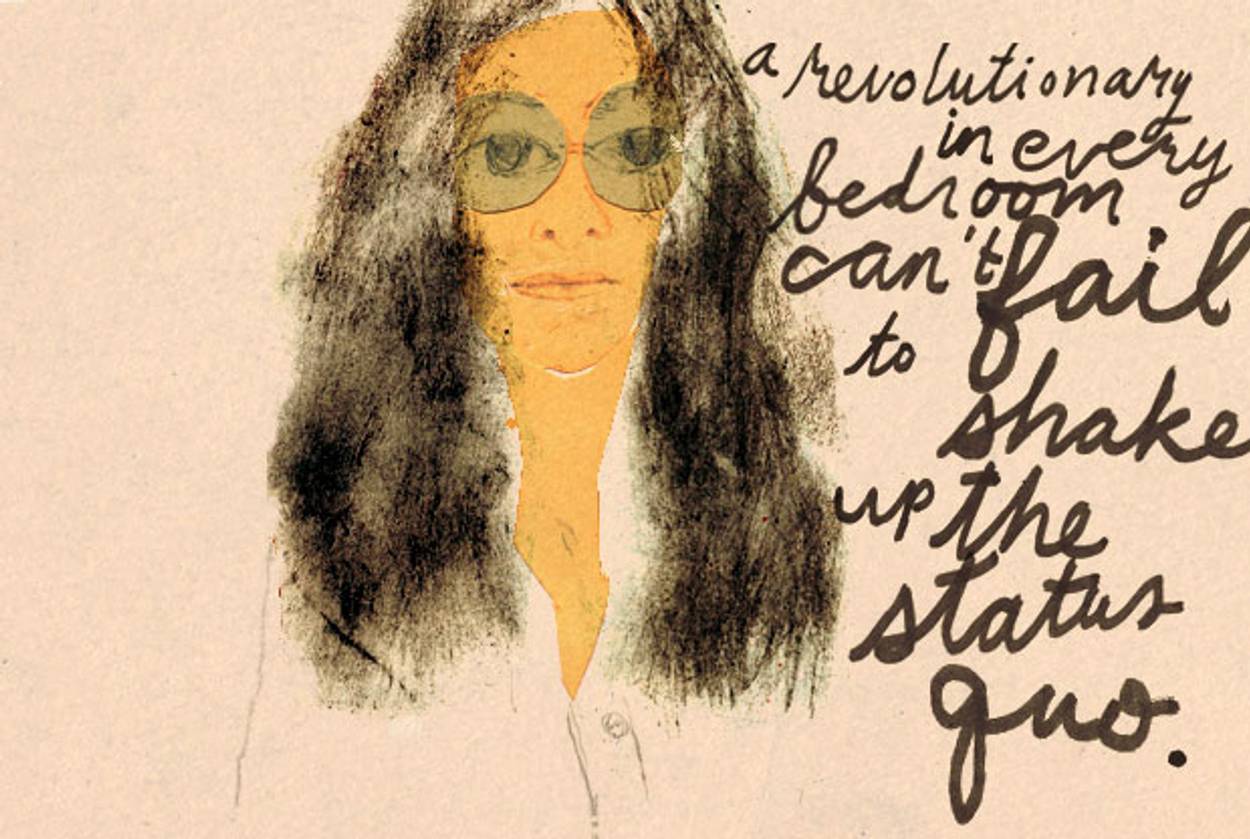

But in the midst of an election cycle that’s still chewing over long-settled debates, I’m realizing The Dialectic of Sex is more than a time capsule of a prescient revolutionary. It’s a reminder to go on the offensive. Much of what’s available to young feminists—confessional Rookie, accessible Jezebel, combative Feministing—has the mark of Firestone’s personal-is-political feminism, but not the urgency. Not the feeling that something extreme must be done, besides electing a left-of-center female politician or ridiculing a sexist asshole with a hilarious meme. Not that I don’t see the value of a well-timed Tumblr—as Ann Friedman quipped the other week at Nymag.com, “It’s not my revolution if I can’t LOL at it.” And as the dozens of Slutwalk marches last year proved, we’re still down to take it to the streets. But what’s missing in an era of less obvious, more insidious sexism is the idea that wild plans must be drafted, that our approach to personal relationships needs to fundamentally change, right the fuck now.

Even as I write these words—on the Internet, no less—they not only sound too rah-rah and straight-faced, but also impossible. Part of being young nowadays is owning up to the reality that it’s become harder and harder to live very cheaply in major cities, to pursue intellectual or activist pursuits unencumbered by student loans or rising rents or insane gas prices. But Firestone wouldn’t accept these excuses. She’d tell me to change these paradigms, too. (And she’d doubtless have some advice for the rapidly fading Occupy Wall Street movement, starting with its muddled message.)

Firestone made every issue more life-or-death urgent than even other radical feminist revolutionaries. “She responded to things pretty lightning-like,” Ti-Grace Atkinson told me, recalling the speed at which Firestone wrote 1970’s The Dialectic of Sex and wrangled the radical feminist journal Notes From the First Year. (Rosalyn Baxandall told me Firestone urged her friends to rustle it up with the quickness so she could personally deliver the collection to Simone de Beauvoir in Paris.) “She reacted to things and moved. She was not a patient woman, which is high praise from me,” said Atkinson. It was an incredibly productive time for everyone, but “Shulie expressed it more dramatically,” Atkinson guessed, because “maybe she felt that she didn’t have a long time to produce.”

Atkinson refers both to the intense, short-lived period of early radical feminism and Firestone’s career span specifically; even though her legacy still looms large on syllabi and in magazine cover stories alike, Firestone left New York and the movement shortly after the explosion of chatter surrounding her book. At that point, she’d had a breakdown, and she spent the next decades grappling with a problem many mentally ill people struggle with: feeling soulless and paralyzed on medication, and unhinged without it. But several early feminists I talked to attributed this abrupt recoiling partly to the success of The Dialectic of Sex itself—the book was suddenly a living, breathing thing. She didn’t own it anymore, and she didn’t control it. She took the subsequent outrage personally.

It was hard not to. Firestone and her co-conspirators were directly reacting to the boilerplate feminism of NOW, which focused solely on changing legislation and pooh-poohed the importance of sex and relationships and everyday power struggles like having to do housework. (My mom told NPR’s Terry Gross in 1989 that not wanting to clean was one of the things that radicalized her.) For professional activists, the line between politics and private life often becomes blurred, but it was especially true of a movement trying to prove that politics existed in the kitchen and the bedroom, not just the courtroom. The legitimacy of this idea has endured (as any number of Atlantic cover stories written by white ladies in the last few years shows). But the notion that these dynamics can radically change is often relegated to a fleeting g-chat conversation or a pot- or whiskey-fueled late-night revelation at a friend’s house.

Of course, Firestone would tell me that these chill sessions are where it starts. In the days following her death, I had a hard time pinning down people who truly felt like they knew her. (At one point I felt passed around the radical feminist underworld like a hot potato—“She was best friends with her!” “No, she was.”) Still, it was clear that Firestone explicitly embraced the power of community in revolution. Atkinson outlined a scenario that echoes my mom and countless other radicals throughout history: “You come to New York, and you’re a weirdo, and you’re so happy to be with all the other weirdos who don’t think you’re weird,” she told me. “[I]t’s surprising, it’s thrilling, it’s like you’ve discovered your twin.”

Ultimately, one of the most radical things about Firestone, perhaps trumping even the Brave New World-like fantasies of reproduction without pregnancy, was the enormous intellectual generosity embedded in her fraught and solitary life. I picked up on this as I scrolled through the three-part Firestone memorial on n + 1. She wrote to Ann Snitow in 1970, in a copy of The Dialectic of Sex: “I, too, basked in your kindness and rare understanding all the long winter that I wrote this book,” even as she scolded such a default female setting. To Alix Kates Shulman, Firestone wrote a handwritten thank you in 1997 for “being a great role model” nestled in a copy of her second book, Airless Spaces, a memoir about her time in a mental hospital.

Reading these made me peek at the pristine copy of The Dialectic of Sex I’d found in my mother’s book collection when she died in 2006, and sure enough, there was a note written in 2002: “Dear Ellen, I’m sending you this complimentary copy of the reissue as I consider you the godmother of this book.” Firestone may have faded from the forefront of the movement, but she left a trail of clues, brief salutes to the relationships that enabled such rapid and radical change, the coalitions that created the improbable scene 43 years later of a father handing his daughter a prescient feminist polemic, lest she miss out on a classic. For people who don’t have dads like mine, there’s always the impetus of loss; a flurry of obituaries tends to breathe life into a fading figure in the form of a slow burn. (It happened to my mother, too.) This piece is itself part of that awakening—hopefully with a few chill sessions to follow.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a writer, editor, and author of Girldrive: Criss-crossing America, Redefining Feminism. Her Twitter feed is @Nona.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a writer, editor, and author of Girldrive: Criss-crossing America, Redefining Feminism. Her Twitter feed is @Nona.