A Mobster in the Family

My husband’s great-uncle was generous and entertaining—and a member of Detroit’s Jewish crime syndicate

In Gangster Squad, a movie opening Friday, Sean Penn plays Meyer “Mickey” Cohen, a ruthless Jewish mobster who operated in Chicago, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles in the mid 20th century. Cohen, like many of his colleagues, was the son of poor immigrant parents who was enticed by the financial rewards of organized crime. In a 1957 interview with Mike Wallace, Cohen recalled, “I got a kick out of having a big bankroll in my pocket. Even if I only made a couple hundred dollars, I’d always keep it in fives and tens so it’d look big. I had to hide it from my mother, because she’d get excited when she’d see a roll of money like that.”

Cohen wasn’t the only Jewish mobster carrying around piles of cash. In fact, I discovered just a few years ago that I’ve got a gangster just like him on my own family tree.

My husband recalls his Great Uncle Sam showering him and his siblings with bills from his bankroll at b’nai mitzvah and other family events. At the time, my husband had no idea that the man behind the bills was actually career criminal Sammy “The Mustache” Norber, an associate of Detroit’s notorious Jewish crime syndicate the Purple Gang. What Cohen was to Los Angeles, the Purple Gang was to Detroit—a Jewish gang feared by even Al Capone’s Chicago mob.

My husband was a teenager when he learned of his great uncle’s true identity, after a front-page news story revealed that Norber had been convicted of stealing a truckload of aspirin. While the family jokes flew (“He must have had a bad headache!”), the seriousness of this information didn’t seem to make a strong impression. While the notion of having a gangster in the family has fascinated me since I learned of Sam’s existence early in my marriage, my husband and his relatives remain nonplused. Their Uncle Sam is remembered more for his great sense of humor than for his career choices.

***

Samuel Norber was born in 1911 in southern Illinois, where his Russian immigrant parents, Aaron and Mollie, had arrived four years earlier along with Sammy’s three older sisters. Aaron sold dry goods to the Italian miners who worked the region’s coal fields. During the 1920s, the family, which grew to include six children, moved to St. Louis. Family lore has it that Sammy was a promising violinist, but instead of practicing, he ran wild in the city streets. It was there that he got a taste for gang life, joining the predominately Irish Hogan Gang. Sammy’s involvement promptly landed him at the National Training School for Boys in Washington, D.C., a juvenile rehabilitation facility. It is not clear whether he was sent to the facility by his parents or by the police. Either way, he didn’t stay long; in 1928, 17-year-old Norber and a buddy escaped the school, slashing their way out of a window screen.

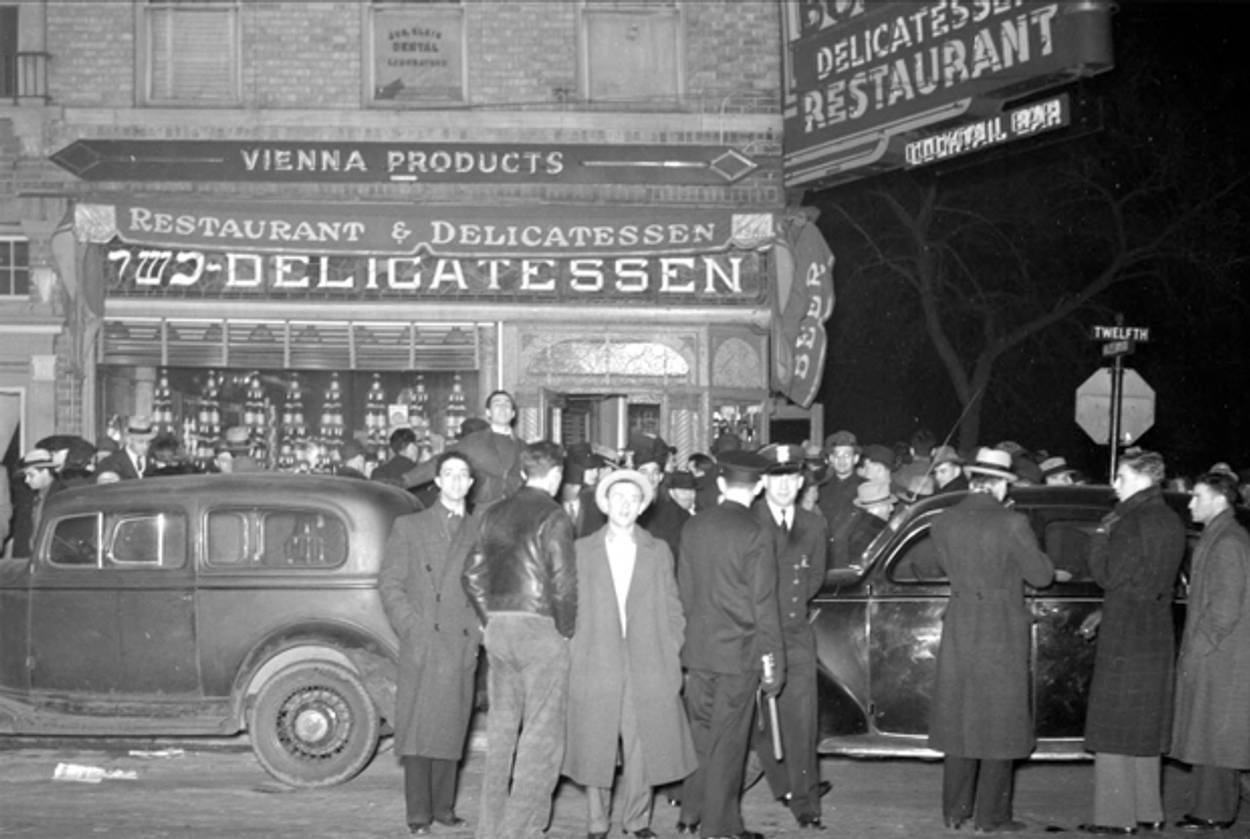

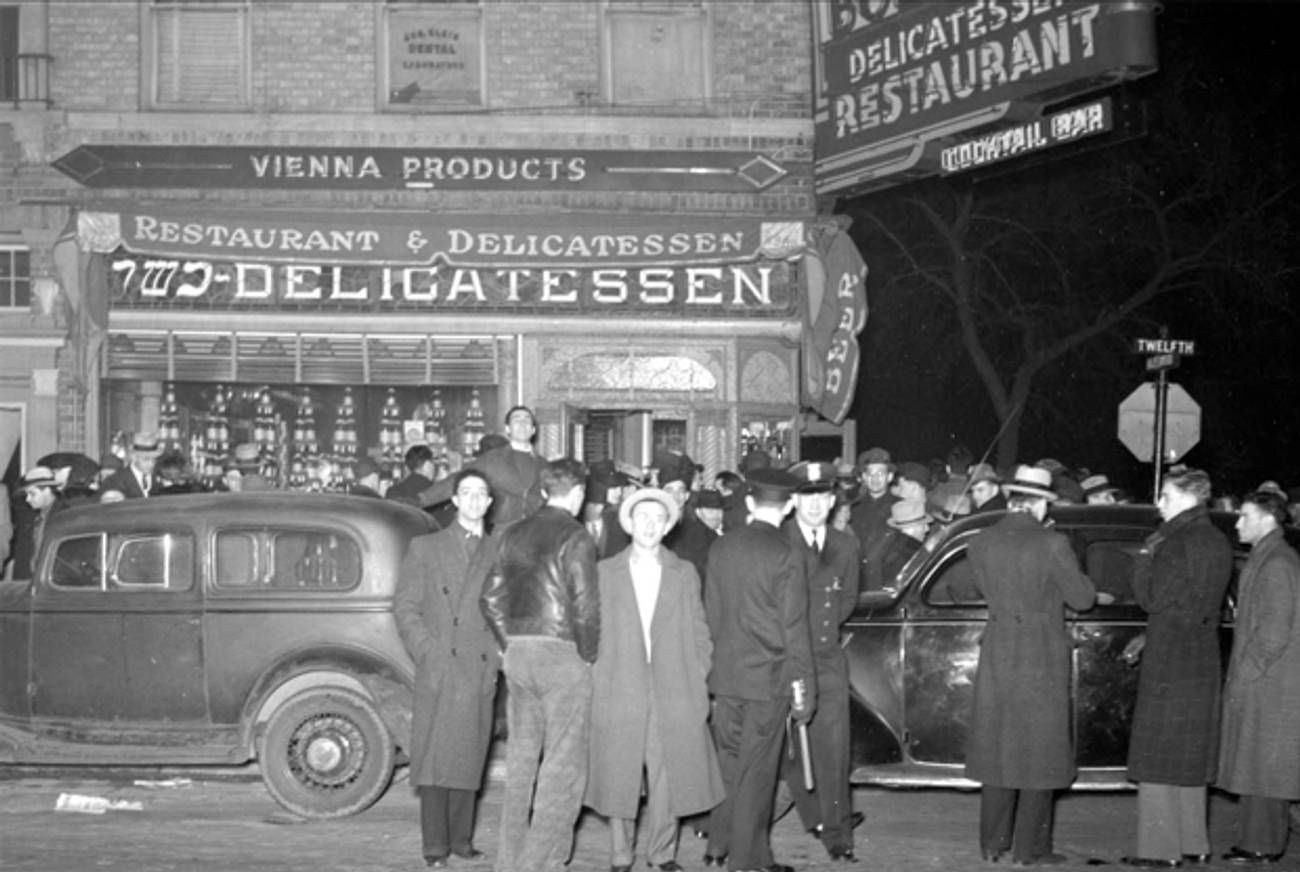

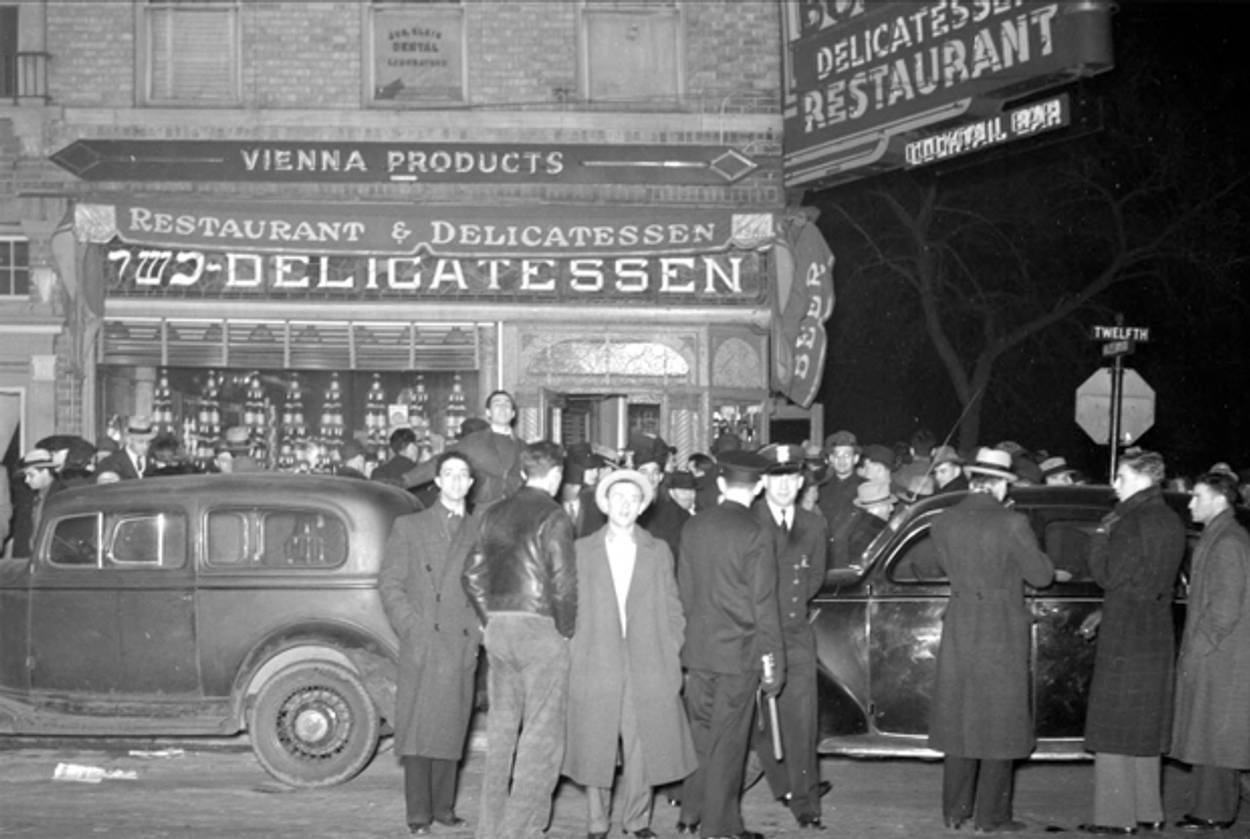

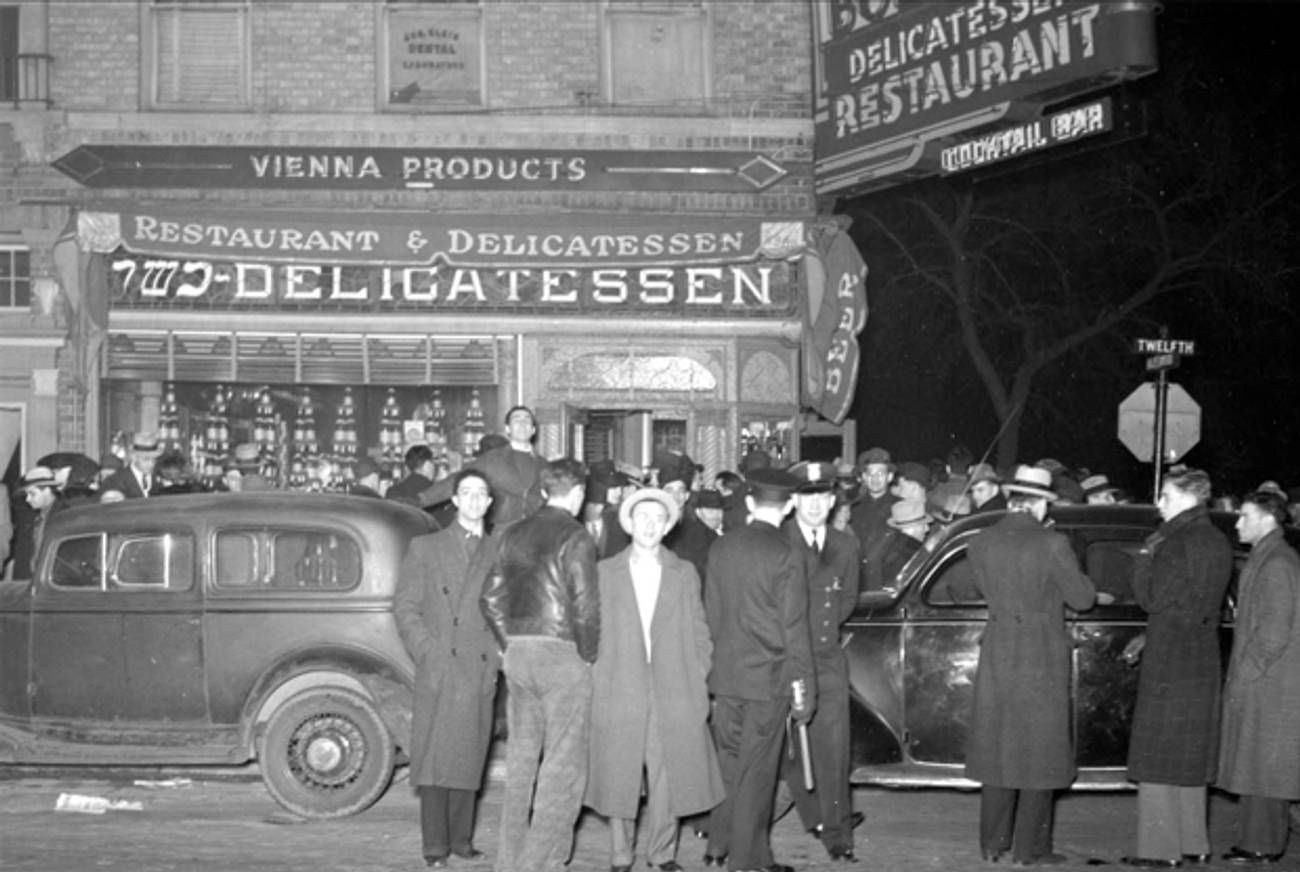

While most of his immediate family remained in St. Louis, Sammy moved to Detroit, where his eldest sister, Sarah—my husband’s grandmother—had set up house with her family. In Detroit, he connected with the Purple Gang. Led by the four Bernstein brothers Abe, Ray, Joe, and Izzy, the Purple Gang started bootlegging during Prohibition, terrorizing the docks, and moving eventually into extortion and murder.

Robert Rockaway, author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters, describes the background of many Jewish mobsters: “The gang members were second-generation Americans whose parents had immigrated from Eastern Europe. Most of the boys had been born in the United States during the first decade of the twentieth century.” These young men, born into poverty and with little education, came of age at the start of the Depression and frequently found themselves barred from desirable job opportunities. Mob life offered promotions, romance, and all the trimmings of corporate America, albeit with a few additional job hazards. Norber, a relative newcomer to the group, claimed the nickname “The Mustache,” distinguishing him from fellow members also named Sam, who took nicknames like “The Gorilla”, “Lefty,” and “Sammy Purple.”

During its heyday, the Purple Gang was of such concern to federal authorities that J. Edgar Hoover himself wrote to the Commander of Naval intelligence in 1934 regarding an alleged Purple Gang plot to destroy the Panama Canal. The plot didn’t pan out, but legend has it that the Purple Gang did control most of Detroit’s illicit activities, in addition to offering protection to Jewish interests under threat from Father Charles Coughlin. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Purple Gang associates also provided union-busting services to business owners—Jews and gentiles alike.

While his siblings built legitimate careers and families, Norber used his skills as a showman and a thief to mastermind thefts—although, according to the family, he stayed out of more violent gang actions. During the 1940s, he took several long “vacations” as a result of his activities, including one to Michigan’s Marquette State Prison, where he was fingered as the kingpin of a prison drug-smuggling ring. Despite receiving a 20- to 30-year sentence for armed robbery, Norber was out on parole by 1950. Always a showman, he used his engaging sense of humor to land emcee gigs at Detroit’s fashionable 509 Nightclub.

Apparently inspired by an impressive 1950 heist of the Brinks armored car company in Boston that yielded the robbers over $1 million, Norber was involved in planning a similar job in Cleveland. On a tip, police tracked him to a Cleveland apartment where they discovered imitation Brinks guard uniforms, but no trace of Norber. Eventually, police caught up with the fugitive and sent him to Michigan’s Jackson State Prison. Norber again put his comedic skills to good use: He emceed prison shows and in 1961, Norber, along with a few other Jackson State inmates, recorded and released a comedy album. The LP, known as Prose From the Cons, was produced by comedian Jackie Kannon with the blessing of the prison chaplain, Rabbi Morris Shapiro.

Once free from prison, Norber and an associate drove to New York City and received 77 boxes of stolen pharmaceuticals in 1964. As the two men steered their truck toward the Lincoln Tunnel, FBI agents arrested them. The case was appealed, and the men were not convicted until late 1968. Meanwhile, Norber stayed out of jail, marrying Esther Goodman in Las Vegas in 1969. Just two years later, he was again indicted, this time for masterminding the aspirin-truck heist.

While the Purple Gang disbanded by the late 1940s due to infighting and long prison terms, Norber remained in the “business,” building alliances with other criminal groups. In the 1970s, he swapped his trademark mustache for a diamond-embedded tooth and helped to finance one of the largest heroin rings in Michigan.

***

While Norber was clearly no mensch, his relatives remember him as being generous, frequently donating items for charity auctions and distributing his rolls of bills. He also maintained strong family ties throughout the years. My father-in-law, Norber’s nephew, recalls being present at one of the mobster’s many trials. Norber’s sister Sarah and her family attended Sam’s prison performances, and Sam even celebrated at my husband’s bar mitzvah in 1972. Another nephew helped take care of Norber after he suffered a stroke.

Although Norber stayed in contact with relatives, there seemed to be no campaign to involve family members in his criminal activities. Rockaway indicates that this was typical of Jewish gangsters: “While American Jewish gangsters were as important as American Italian gangsters, many of whose crime ‘families’ remain to this day, with the Jews, it was that one generation, the second generation, the children of immigrants, and it ended with them.” In my husband’s family, it ended with Uncle Sam.

Some people would argue that Norber’s generation of Jewish Americans had limited opportunities to make money, and that’s what drove them to a life of crime; others think that’s letting them off the hook. If Mickey Cohen and Sam Norber had been born a decade or two later, when the post-war GI Bill and reduced anti-Semitism opened more doors for Jews, would they have pursued legitimate careers? Or would they have led a life of crime under any circumstances?

Norber died in 1995 and is interred in Detroit’s Hebrew Memorial Park. While I never met him, his story has intrigued me for years because it stands in stark contrast to my own upbringing. As a second-generation American, raised in the post-war era, I was taught to follow the rules, to always remain above suspicion. Worried that all Jews may be condemned because of the actions of a few, I cringe when fellow Jews were convicted of wrongdoing. A part of me fears that even the perception of Jews as criminals places us one step closer to scapegoating and other horrors. However, examining Sam Norber’s life has helped me to recognize that his actions and those of other Jewish gangsters represent all Jews no more than Al Capone characterizes all Italian Americans. Armed with a new understanding of the man behind the gangster cliché, I now choose to see Sam Norber as the flawed individual that he was: colorful, clever, and corrupt. And a member of the family.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and editor of Legacy, the publication of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and a past president of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.