The Haftarah Reading That Inspired Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’

King’s speech draws on a part of Isaiah that Jews recite after Tisha B’Av—offering a model for revitalizing his mission

Every January, Americans observe Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Rather than celebrating a broader Civil Rights Movement Day, we prefer to tell the story of a singular hero who represented and led the struggle for justice and equality, giving his life for it long before his work was done. And King—in spite of his well-documented personal flaws—gave us exactly the story we need. This story speaks not only to the reverend’s fellow Christians, but to Jews as well.

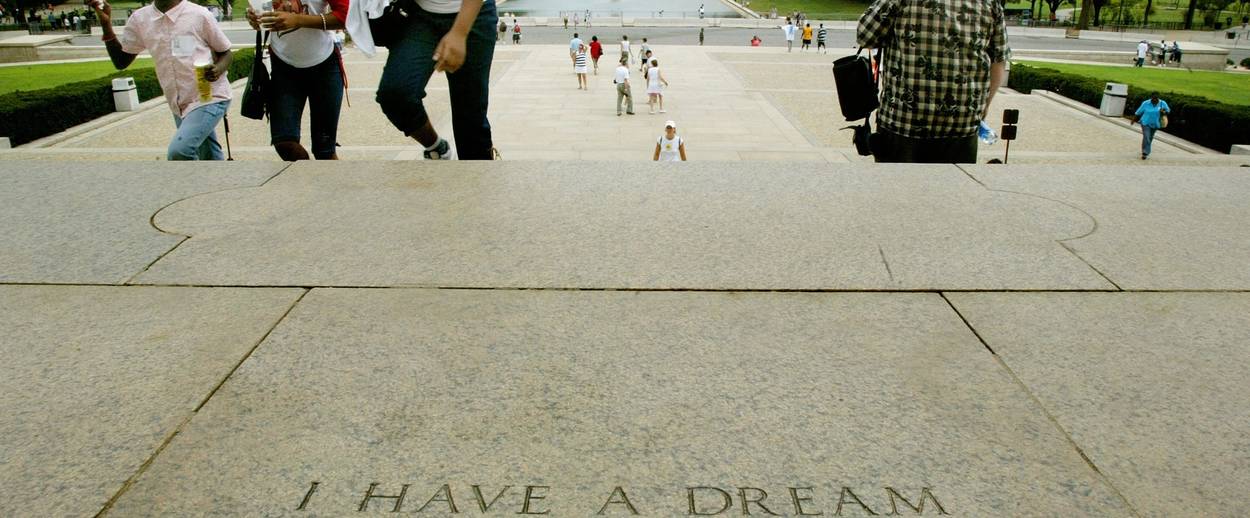

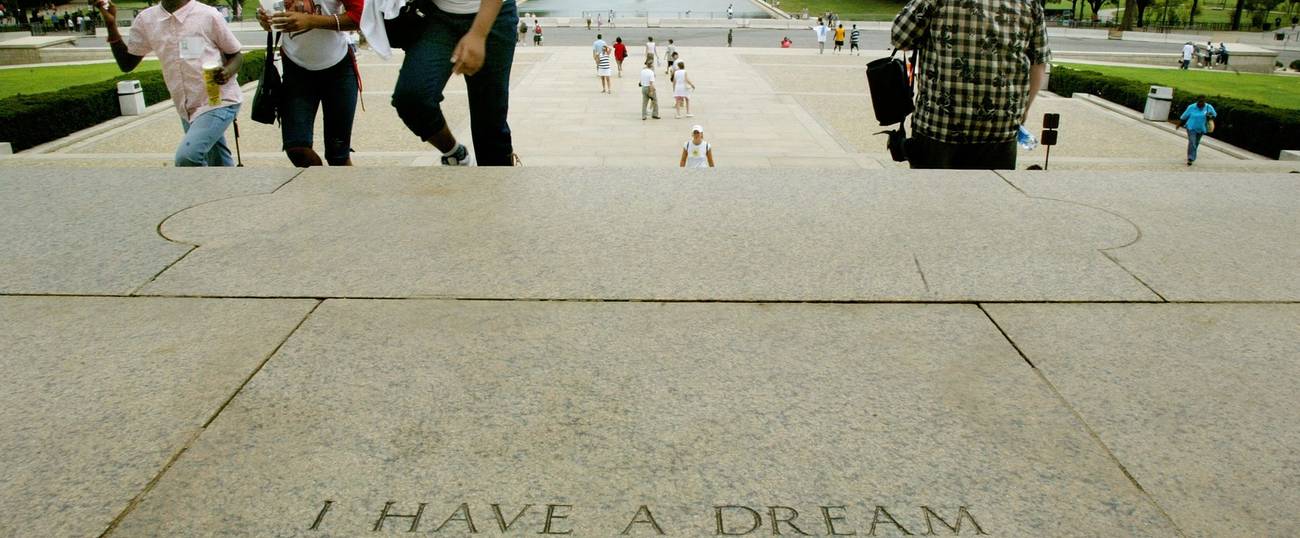

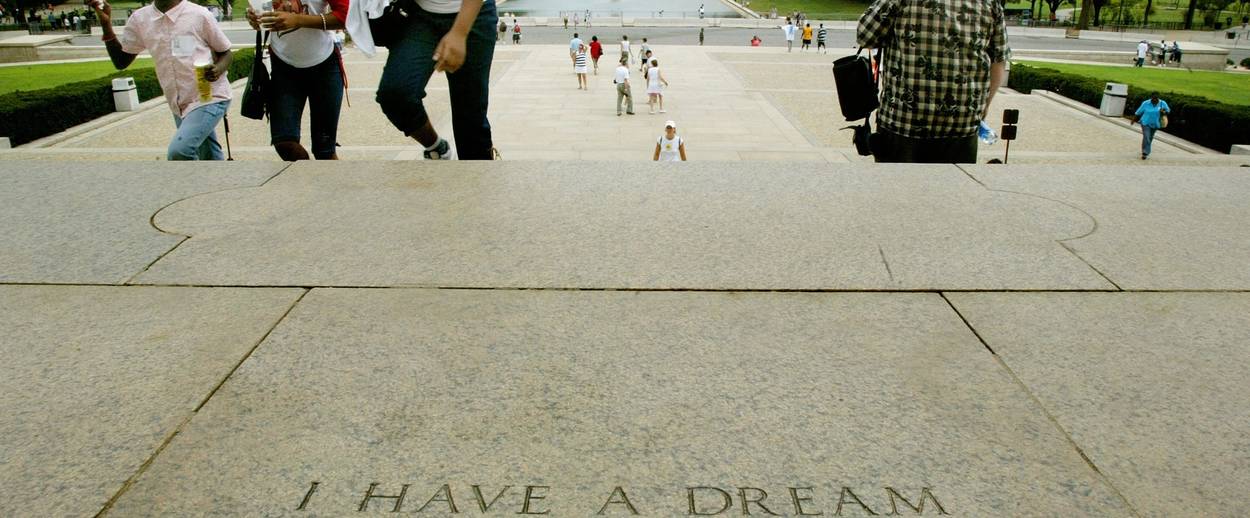

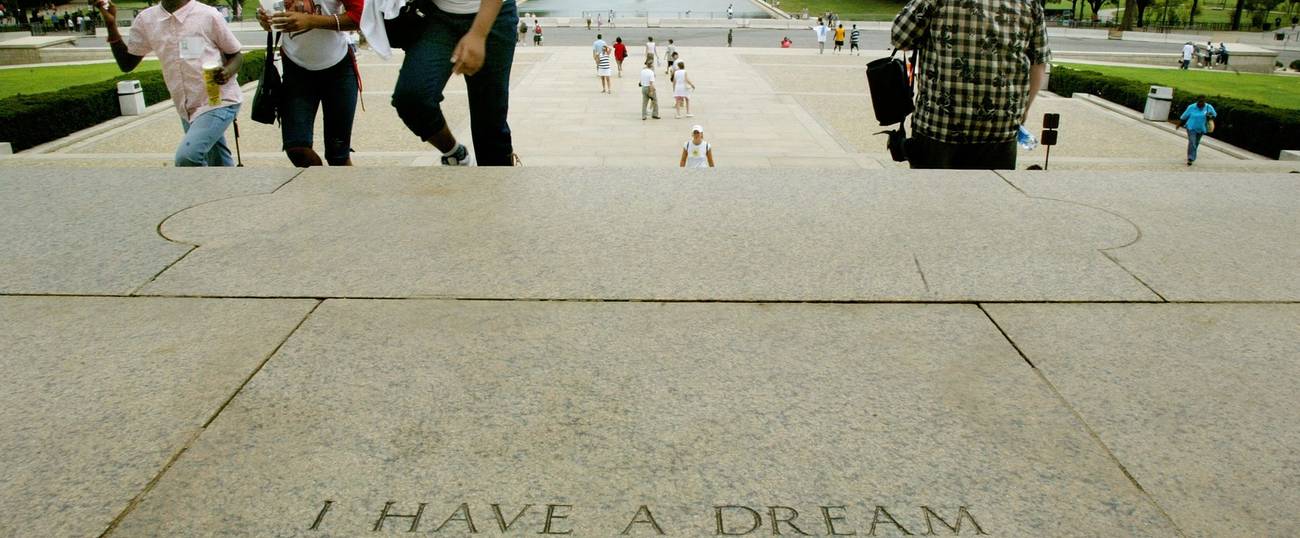

In calling for black people to be included in American society, King grounded his demands in the nation’s most sacred texts: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bible. King’s approach thus set him in dialogue with the other received American traditions, Christian and Jewish alike, that accompany these texts. In 1963, King led the historic March on Washington and delivered the rousing “I Have a Dream” speech by which we best remember him. He famously referred to the nation’s founding documents and the Emancipation Proclamation and also quoted this bit from Isaiah 40:

I have a dream that one day “every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

These powerful words link the goal of racial equality with the greater promise of harmony and divinity. They aroused King’s massive audience to action in 1963, the Protestants in attendance hearing a charismatic preacher revive their Social Gospel and the Catholics hearing him echo their liberation theology. The Jews who heard the speech—both those who physically attended the event and those who have studied and cherished his words in the five decades since—likely found the southern preacher’s style less familiar to their religious experiences. But many have undoubtedly been reminded of the haftarah.

The “Nahamu nahamu ami” haftarah reading, from which the Shabbat following Tisha B’Av draws its title, also excerpts from Isaiah 40. As the first of the seven “haftarot of consolation” read between Tisha B’Av and Rosh Hashanah, Nahamu presents a prophetic vision calling upon the nation of Judah to provide solace to the suffering city of Jerusalem. God announces, after extracting a price for Jerusalem’s sins and allowing the city’s recovery, his imminent arrival to raise the valleys, lower the hills, smooth the rough places, and straighten the crooked places—a full and final restoration of justice.

Awkwardly enough, though, the rabbinic tradition of reading this particular chapter on this particular Shabbat seems anachronistic. The explicit historical context of Isaiah 40’s message of comfort is the conquest of the kingdom of Judah and siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib, king of Assyria, circa 701 B.C.E. The subsequent destructions of Jerusalem, by a Babylonian king in 587 B.C.E. and a Roman emperor in 70 C.E., actually appear to contradict Isaiah 40’s tone of finality. But the rabbinic institution of reading this chapter after Tisha B’Av frames the Nahamu message as if responding to the tragedies recalled on Tisha B’Av, most notably those same later destructions of Jerusalem.

The haftarah tradition thus embraces historical tension and communicates a message of stubborn resilience and bold adherence in the face of calamity: When prophetic promises fail to actualize, Jews are not to reject these promises but to understand them as applicable to a future moment and to keep striving. How appropriate for Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

From the distance of half a century, we can reflect usefully on King’s legacy and his entry into the national canon. The man has become emblematic of the better angels of American nature and American values. “All men are created equal” is now as much his as Jefferson’s, “Let freedom ring” as much his as Samuel Francis Smith’s, and “the Promised Land” as much his as Moses’. Still, the goals left unfulfilled remain the awkward subtext of our annual holiday celebrating this national icon. As per Pew Research studies in 2013, since King’s 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (the event’s full formal title) the unemployment rate for black Americans has consistently remained about double that of the white population, and the rate among Latinos about 1.5 times the rate among whites. Despite promising new data concerning the wages of millennial women, Pew reports American women as a whole are still paid about 84 cents per dollar earned by American males. The wage gap between black women and white males is closer to 64 cents per dollar, between Latina women and white males 54 cents per dollar.

And new frontiers in the active struggle for civil rights emerge constantly. The Trayvon Martin tragedy divided Americans and highlighted the deep prevalence and influence of race-based perceptions of danger in American society. The U.S. Sentencing Commission found this year that, since the Supreme Court’s 2005 restoration of judicial sentencing discretion, the sentencing gap has widened between the races, with black men serving 20 percent longer than white men convicted of similar crimes. And perhaps most prominent among today’s fault line issues, 33 state governments still limit full marriage rights to opposite-sex couples. Nearly 46 years after King’s death, the battles for justice and equality continue, and without effective leadership.

The Nahamu ethos can guide Martin Luther King Jr. Day to transcend its role as a reminder of a chapter in America’s past. Recalling King’s echo of Isaiah 40 as an annual tradition, just like the rabbis of antiquity did to the same passage 2,000 years ago in Nahamu, allows the prophetic promise to outlive its original historical moment. King married the traditional texts of America to his mission and thereby deeply affected their meaning. The case of Isaiah 40 illuminates a path for these texts and their adherents to return the favor and revitalize King’s civil rights mission going forward.

Charles Kopel is an undergraduate student of history at Yeshiva University.