Leaving Israel, Russian Jews Find a New Home in Halifax

Drawn by the cool climate and slow pace of life, hundreds of immigrants bolster the small Jewish community in Nova Scotia’s capital

For Olga Shepshelevich, Halifax in spring smells like home. “Sometimes I walk here, and I can smell the scents of flowers I used to smell in Chernovitz,” she told me recently. “It reminds me of when we were children, so it’s great.”

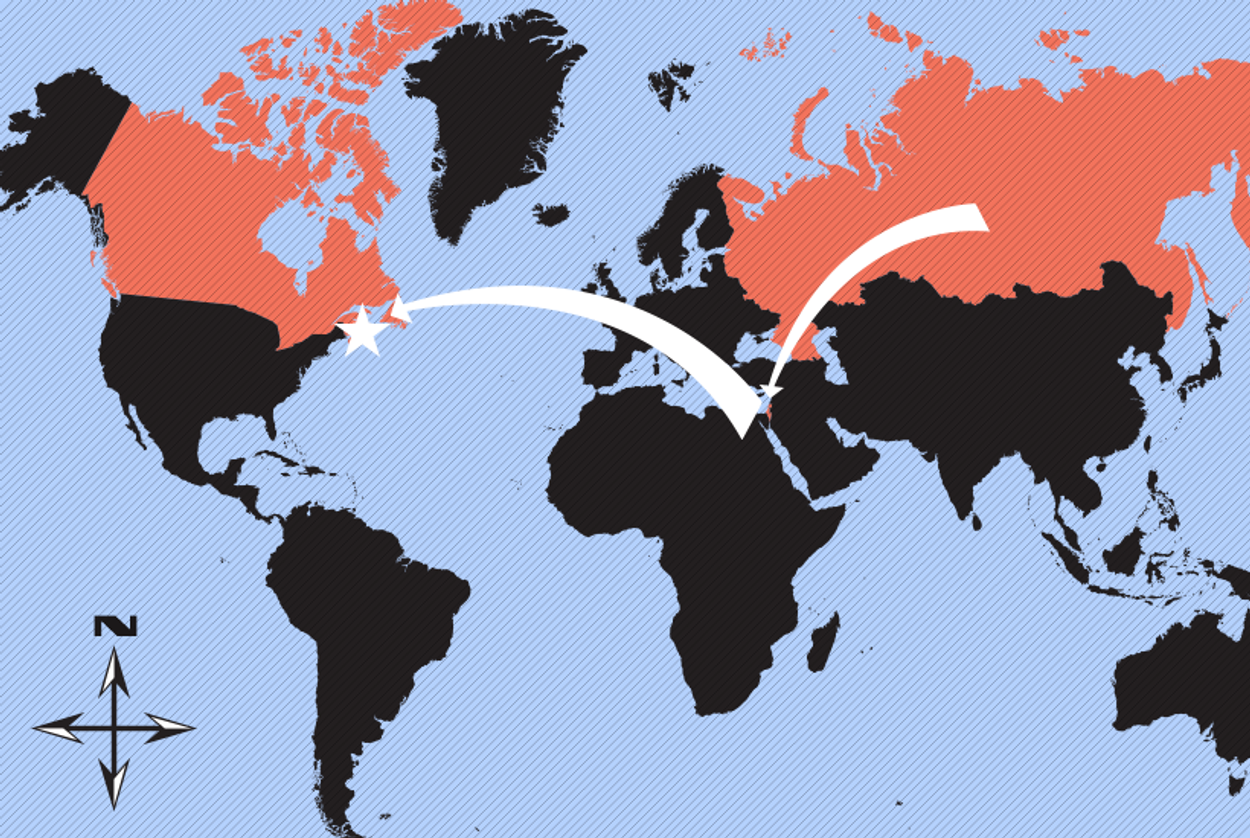

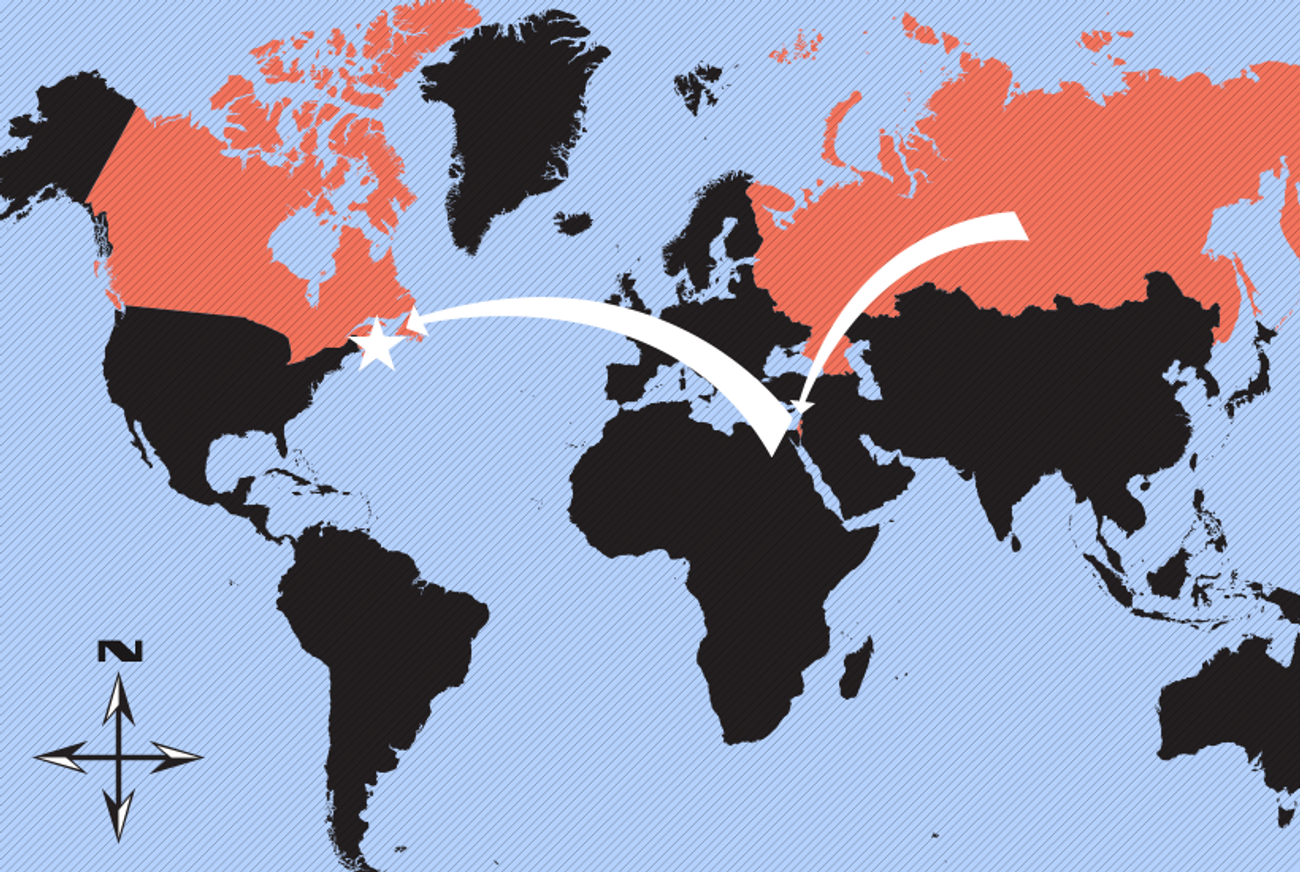

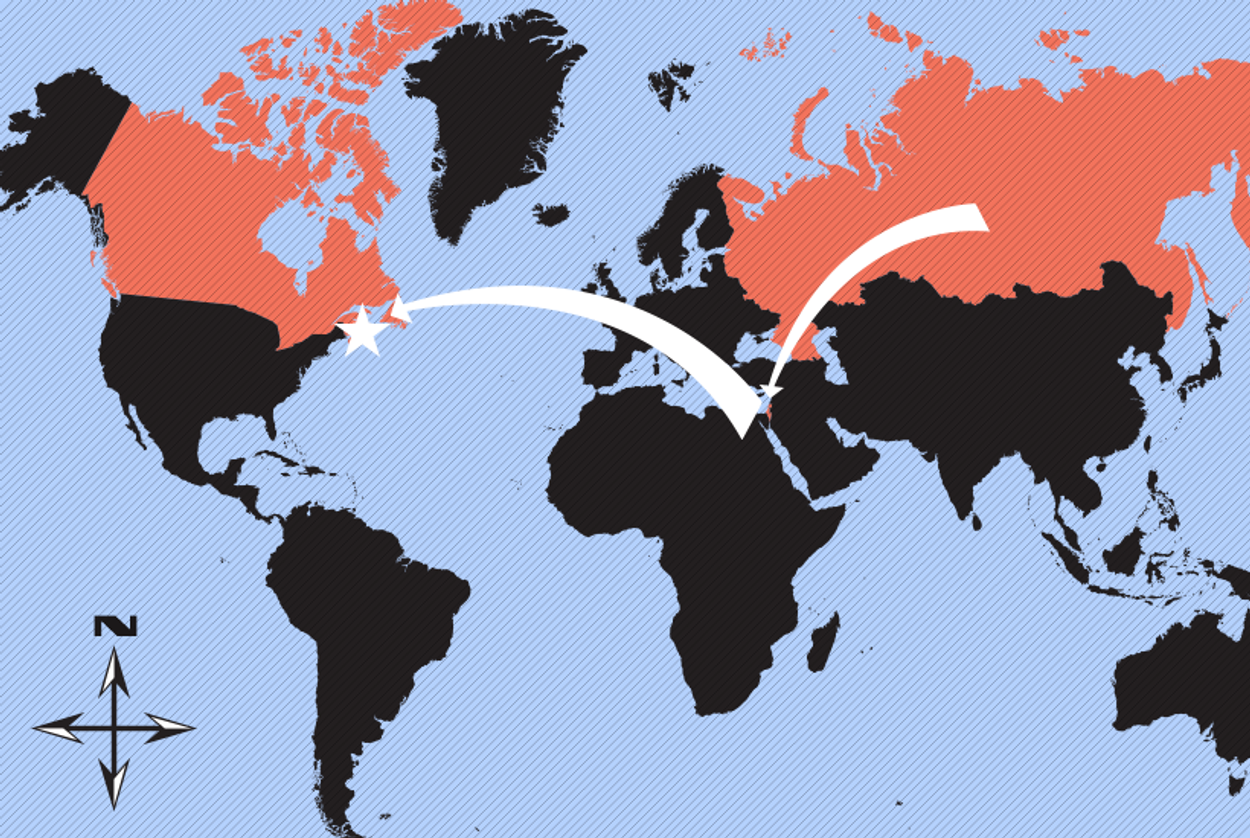

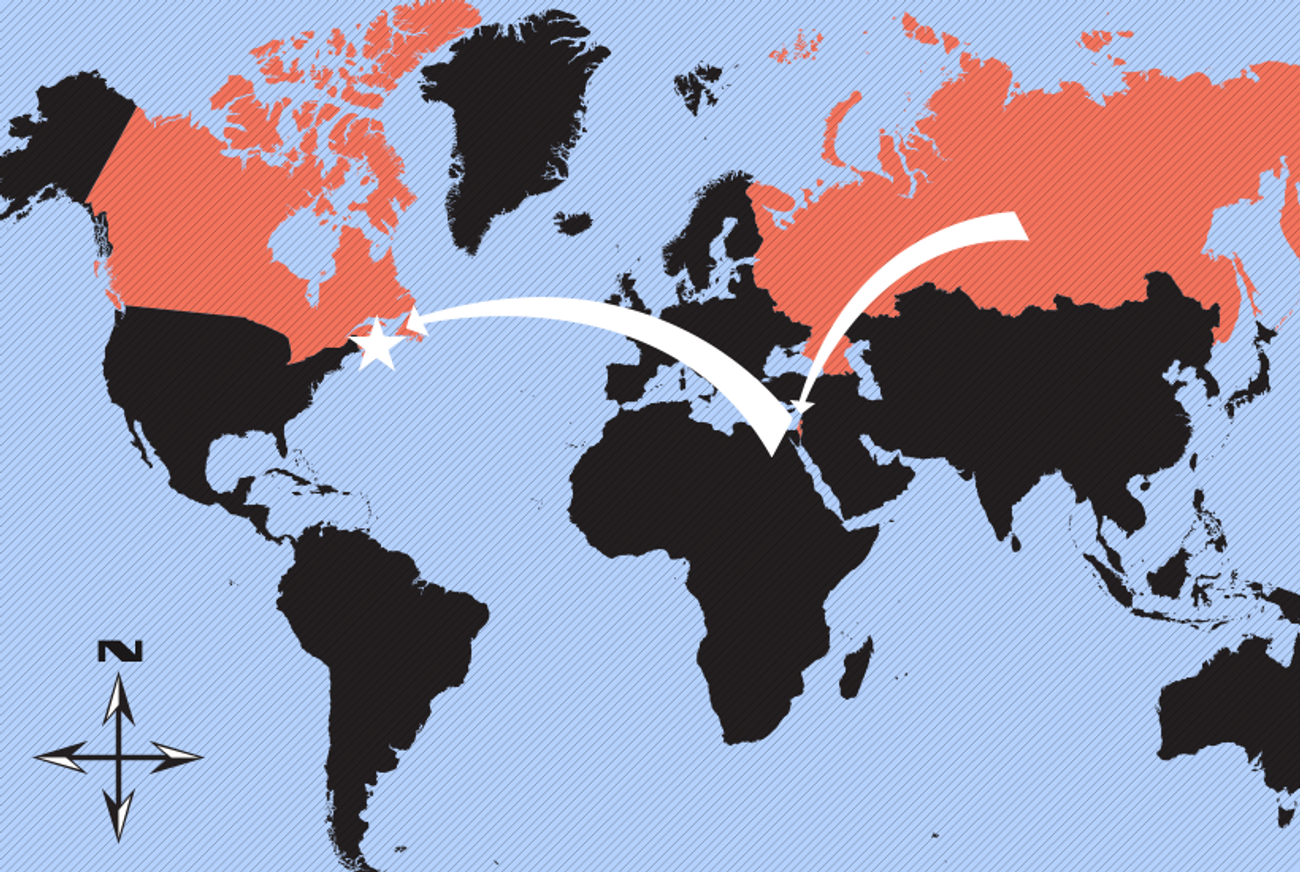

Shepshelevich, 32, grew up in western Ukraine. As a teenager, she traveled to Israel to attend high school in Jerusalem as part of the Na’ale Program; after she graduated, she wound up staying in Israel—living on a kibbutz, serving in the army, and eventually becoming a customs officer. But she and her husband Gregory were looking for a quieter life, and a few years ago, “someone I knew in Israel who had friends who had emigrated told me there is a Jewish community in Nova Scotia,” she said in a recent interview. “I started looking for information on the Internet, and we started to think about it.”

Specifically, she began to research Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia. While the city boasts Canada’s largest Jewish community east of Montreal, that population is still small: roughly 1,500. As part of an effort to bolster the community’s numbers, the Atlantic Jewish Council, whose office is in Halifax, has courted Israeli Jews with roots in the former Soviet Union to see if they’d consider immigrating to Canada.

Six months ago, Shepshelevich, her husband, and two young children finally made the move. And they’re not alone: According to Gerry Mills, director of operations for the nonprofit Immigration Settlement and Integration Services, 302 Russian Jews moved from Israel to Halifax between 2009 and 2012, and there are nearly 100 more on the way. Those may not be huge numbers, but for Halifax’s small Jewish community they will make a noticeable impact.

***

Halifax was founded in 1749, and its first Jewish resident arrived a year later. By 1911, there were 1,360 Jews—almost exactly the same number as there are today, even though the population of the city as a whole (currently nearly 400,000) has increased substantially in the last century. The Jewish community hasn’t grown because young people tend to leave, if not for work, then for marriage. “That’s what happens here all the time,” Jon Goldberg, executive director of the Atlantic Jewish Council for the last 24 years, told me. “That’s what’s driven the population since the war. If they didn’t get hooked up with a Jewish man or woman after university, they were gone to Montreal or Toronto.”

At the Orthodox Beth Israel synagogue, which was founded back in the late 1800s, Rabbi Amram Maccabi said that most of his congregation is “between the ages of 50 and 90, with no next generation afterward. It’s like we’re missing two generations completely.”

Faced with this looming demographic apocalypse, Goldberg and his organization decided to turn to immigration, a subject he admits they knew little about. “I’m not in the immigration business, I’m in the Jew business,” he said. Someone had suggested to Goldberg several years ago that the community look to Israel for immigrants. “I threw him out of my office,” Goldberg recalled, offended by the notion of luring Jews away from Israel. But upon further examination, Goldberg decided that Israel might be the right place to start after all—with a few important caveats.

First, the AJC restricted its pitch to Russian Jews in Israel. Thousands of Jews who had made aliyah from the former Soviet Union were later leaving; as long as they were already leaving, the thinking went, there seemed to be little harm in trying to entice them to immigrate to Halifax. After all, there are more than 15,000 Jews in Toronto who speak Russian at home, and thousands of Russian Jews have moved to Winnipeg. “So my board said yes, on one condition,” said Goldberg. “We can handle it in our minds if they or their parents are from the former Soviet Union—but no native-born Israelis. They felt that would go against our Zionist function.”

For Maccabi—who is himself Israeli-born and has been in Halifax for two years—there is no contradiction in being Zionist and helping Russian Jews leave Israel. “Israel is not the perfect place for everybody,” he said. “I hear this criticism from people here who have never lived in Israel. At least these people tried living there for 15 years. Who are you to judge them?” Conservative Rabbi Ari Isenberg of Shaar Shalom synagogue—just down the street from Beth Israel—voices a similar view: “There are many ways to be Zionist. We live in the Diaspora and find ways to reinforce our Zionism, even in Nova Scotia.”

The AJC also decided to target people who identify as Jews but are not particularly religious. “We don’t look at people who are Orthodox,” said Edna LeVine, the AJC’s director of community engagement. “And you know what? People who are Orthodox don’t want to come here. They ask, ‘How many kosher butchers are there? How many Jewish bakeries? How many Jewish community centers?’ and our answers are: ‘None, none, none.’ ”

But is it fair to bring Jews to a city with little Jewish infrastructure? “We’re not like Montreal, Toronto, or Calgary, but we do have two synagogues and a vibrant population,” said Halifax Mayor Mike Savage. “We want Jewish immigrants to come here and raise their families, and as that happens we’ll develop the infrastructure.”

Savage—who was the emcee for a Jewish National Fund Negev dinner that drew 700 in May—says that, like the Jewish community, Halifax as a whole needs immigrants. And he recognizes that the city can play a greater role in making them feel welcome. “I think Atlantic Canada was a bit behind the curve on immigration,” he said. “While provinces like Manitoba were actively pursuing immigration, here there was a question of whether immigrants were creating wealth or taking wealth.”

A report on the future of Nova Scotia’s economy released in February (with the dire title “Now or Never”) calls increased immigration “essential”—a view that Savage strongly echoed: “The bottom line for me is cities that don’t grow don’t prosper,” he said. “There aren’t many cities declining in population and doing well.”

Once the AJC decided to take the plunge and seek out immigrants, they had to figure out the logistics. Goldberg usually makes an annual trip to Israel, in part to check on projects the AJC helps fund, and in 2008 he was invited by an immigration consultant to address potential immigrants. Over 200 turned up. The agency continues to work with local immigration consultants, and Goldberg interviews applicants when he is in Israel. Interest remains high, Goldberg said, with potential immigrants attracted to the pace of life in Nova Scotia, educational opportunities (Halifax has six universities and a community college), and the climate.

In Canada, immigration is a federal responsibility, and the wait for approval can be long and arduous. But provinces have their own nominee programs, allowing them to identify immigrants with skills and resources they need and to fast-track them. The AJC program started off as part of the “community-identified stream” of the Nova Scotia nominee program. Essentially, it allowed communities to write to the provincial government expressing support for particular immigrants. That program has now been eliminated in favor of one that focuses on job skills, but Goldberg doesn’t see that as much of a problem, since the AJC can continue to help facilitate applications and the government has said that letters of support will continue to carry weight in assessing applications. The program is open-ended, LeVine says, with funding coming from the existing AJC budget.

Immigrants, of course, are free to leave whenever they like, but the AJC claims a retention rate of 80 percent, which is high in a province that sees many—both newcomers and native-born—“going down the road” to Toronto and Montreal.

As for how Israel feels about all this, Joel Lion, the Israeli consul general for Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces, doesn’t see the AJC efforts as encouraging people to leave Israel, but rather as encouraging those who have already decided to leave to come to Halifax. “We are well aware about the AJC’s initiative, and they do not promote immigration to Canada, but rather are convincing families already recognized as landed immigrants by the Canadian government to settle in their community,” he said in an emailed statement.

***

Slava Svidler, 44, his wife, and two sons were among the first Russian Jews to come to Halifax when the AJC’s effort started. They arrived in 2009, after living in Israel for 13 years. Like Shepshelevich, Svidler sees the cooler Canadian climate as attractive, as well as the small city’s pace of life. “I was born in Russia, and my wife, too—and we feel more comfortable in weather like this,” he said. “We love Israel, and we love the Israeli people, but there is a lot of stress. Israel is a hot place, and not just the weather. It’s more emotional. Here it’s more peaceful.”

Like many immigrants, Svidler has had trouble finding what he calls “a suitable job” in Halifax. Unable to find work as a food technologist, he trained as an accounting and payroll manager and is now in the process of starting a company to provide at-home health-care services, primarily for seniors.

But while he’s had a hard time integrating into the job market, he has found acceptance into the local Jewish community. “It’s a very old community. The majority of people in the synagogue are seniors, but people are open and friendly,” he said. “It depends on what kind of person you are. If you are open and go to the synagogue to meet people it’s no problem. But if you don’t want to do it you will be alone in your bubble.”

Peter Svidler, Slava’s 18-year-old son, who just graduated from high school and is staying in Nova Scotia for university, says his family’s Jewish identity has become stronger since they moved to Halifax. They have a kosher kitchen for the first time, although buying kosher food consistently is nearly impossible. (Ask for matzoh at a supermarket and you’re more than likely to be directed to battered frozen mozzarella sticks.) “My dad and I both noticed that our Jewish identity was actually strengthened by arriving here in Canada, simply by the fact that not everyone is Jewish and so you develop a sense of community and attachment,” he told me. “When you’re in Israel you don’t get the kind of connection that you do with Jewish people here, where it’s a small, tight-knit community.”

Being in a small community has its limits though, and that’s one of the reasons Peter Svidler says he values Camp Kadimah, a Jewish summer camp in Nova Scotia that attracts youth from larger centers such as Toronto. Svidler attended as a camper for several years and is working there this summer. “Being immersed in Jewish life at the camp was refreshing,” he said. “There were conversations and jokes—the occasional joke about Seder or Pesach—that you could make, that people back in Halifax wouldn’t understand. As small as it sounds, it makes a big difference.”

Not everyone’s integration has been as smooth. Neli Shpoker, 32, who immigrated to Halifax with her husband and two children in 2011, sees the community as “unfortunately pretty divided. On the one hand, the local Jewish community [is] very interested in the immigrants from Israel. On the other side, they can’t understand that being an immigrant means you can’t make the same amount of donations, you have different priorities because you have to find a job, and settle in your job.

“One of the complaints I heard is that people are bringing their kids late to the Hebrew school,” she explained. “Someone who is an immigrant can’t tell their manager, ‘I’m sorry, I have to take off at 4:00 on Tuesday because my child has to be at Hebrew school at 4:30.’ ”

While there may be challenges for the older community to accept the newcomers, Maccabi says they have little choice. “They are the natural continuation of this place,” he said. “Without them, there is no future for the Jewish community in Halifax.”

Besides, he added, the city’s Jewish past was dependent on Russian immigrants as well: The families who first formed the synagogue came to Canada after fleeing anti-Semitism in Russia and other Eastern European nations. “The roots of many of the Jews here are Russian,” he said, “but they have forgotten it.”

Shepshelevich said that since arriving in Halifax, she has found herself starting over as a member of a minority group—although that is nothing new to her. “In Ukraine we were called Jewish, in Israel we were called Russian, and here we are Russian Jews,” she said, “but I’m fine with that.”

Beth Israel board member Irwin Mendleson, an optometrist born in Sydney, Nova Scotia, says there has been a process of learning on both sides. He thinks members of the established community may have expected too much, too soon. “The people they’ve brought in are Jewish but very secular, and many of them don’t have a lot to do with synagogue life,” Mendleson said. “I don’t know if they did what the community expected of them at first. But at the beginning everyone expects a lot. I think it will take at least five years. In a few more years I think they will be more fully integrated.”

Both Maccabi and Isenberg say that since the newcomers began landing in Halifax, attendance at large events such as Purim, Israel Independence Day, and Hanukkah celebrations has shot up—with many of the attendees newcomers, and the average age younger than it has been in years. That doesn’t necessarily translate into many synagogue memberships, but it is a first step.

Because Halifax’s Jewish community is relatively small, Isenberg is confident that newcomers like the Svidlers will eventually gravitate to the synagogues, even if they are not particularly devout. “In the Diaspora, the synagogue remains the focal point and gathering spot for Jewish identity. In Israel there are multiple venues and multiple ways that one can experience their Judaism,” he said. “So for an Israeli who moved to the Diaspora, it would seem that there would be a natural period of transition during which time that individual begins to discover that their connection to Judaism ultimately revolves around the synagogue.”

Maccabi is not particularly concerned about the newcomers being secular—especially since few in his congregation are very observant. “This place is Orthodox when they come into the shul. But nobody lives the Orthodox way outside, except for a few families,” he said. Over the last two years he has seen a marked increase in interest, though. “In the four years before I came here, there was one bris. There were tens of kids born. One bris. In the past two years we’ve had 10 circumcisions, seven bar mitzvahs, we’ve placed over 30 mezuzahs, we’ve koshered houses—we did not force anyone, we just said, ‘We are here for you,’ and they wanted to be part of the place.”

Slava Svidler said he goes to Beth Israel not because of a more Orthodox faith, but because it is familiar. “We don’t understand this Conservative or Reform Judaism. For us it’s abracadabra. We are not religion people; we are just traditional.”

And Shepshelevich, who works part-time as a campaign administrator at the AJC (with a poster of the Western Wall on one side of her desk and a Nova Scotia postcard on the other), offers a similar view. “For me personally, community life is much more important than religious life,” said Shepshelevich, who doesn’t attend services herself but is friends with both rabbis on Facebook. (Her husband “sometimes” goes to Beth Israel, she said.) “I’ve never been a religious person. We do want to keep our Israeli heritage and the language for the children. We want to stay connected to the community and to Israel, and my son goes to the Hebrew school. We are all Jewish, and this is something that’s supposed to connect us. It’s complicated, but life is complicated.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Philip Moscovitch is a writer and radio documentary producer in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Follow him on Twitter @PhilMoscovitch.

Philip Moscovitch is a writer and radio documentary producer in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Follow him on Twitter @PhilMoscovitch.