Can Jewish Renewal Keep Its Groove On?

After the death of Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, the mystical Renewal movement faces the future

In the dead of New York City winter each year, roughly 100 people don their winter coats and trek through the cold Upper West Side streets to attend the Romemu congregation’s annual “Roots to Fruits” Tu B’Shevat Seder, their way of marking the agricultural festival. Led by Romemu’s Rabbi David Ingber in the community center of the West End Presbyterian Church, Seder-goers partake in the ritual meal, featuring fresh fruits and wine.

On regular Friday nights, the cavernous prayer hall is filled with 400 to 500 worshipers welcoming the Sabbath, beginning with a silent meditation, and slowly erupting into ecstatic, joyful prayer. Like Friday night services, the Tu B’Shevat Seder—being held this Sunday—draws heavily from Judaism’s rich mystical tradition. Everything at the Seder is shrouded in symbolism and meaning: Fruits that have tough outer skins but soft insides represent life’s struggles, and pitted fruits represent endeavors that initially seem easy, get more difficult, and then flourish. Between drinking four cups of wine of different colors, “reflecting the four Kabbalistic worlds,” as Ingber explained, along with eco-conscious fruit rituals, participants sing, dance, and chant.

Romemu’s songs and chants, which are also sung during weekly Shabbat prayers, are instrumental in helping participants “engage in reflective and contemplative practices to deepen the relationship between the rituals and our own lives,” Ingber, who grew up Orthodox, explained. Romemu’s chants and prayer are based on traditional Jewish liturgy, accompanied by complementary musical arrangements: “We take our davening seriously,” Ingber said.

The tempo of the Friday night service is spiritually thrilling. One moment the congregation may be dancing euphorically, and minutes later Ingber will instruct his congregation to close their eyes and prayer books and meditate in silence. Musical instruments, a weekly poem, and liturgical innovations, including the adaptation of the popular gospel song “Sanctuary,” all contribute to a unique prayer experience.

What Ingber does at Romemu, unusual as it is, is becoming more common. Romemu’s blend of energetic prayer, body awareness, mystical yearning, interfaith cooperation, and egalitarianism is typical, or as typical as any one community can be, of what’s called the Jewish Renewal movement.

Renewal Judaism emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s as a New Age expression of Judaism. “They connect with young Jews who are seekers, disaffected with suburban Judaism, but quite certain that Judaism needs to be revitalized,” said Jonathan Sarna, a historian at Brandeis University. Renewal was essentially an attempt of “translating Hasidism into an American medium,” said Shaul Magid, author of American Post-Judaism: Identity and Renewal in a Postethnic Society.

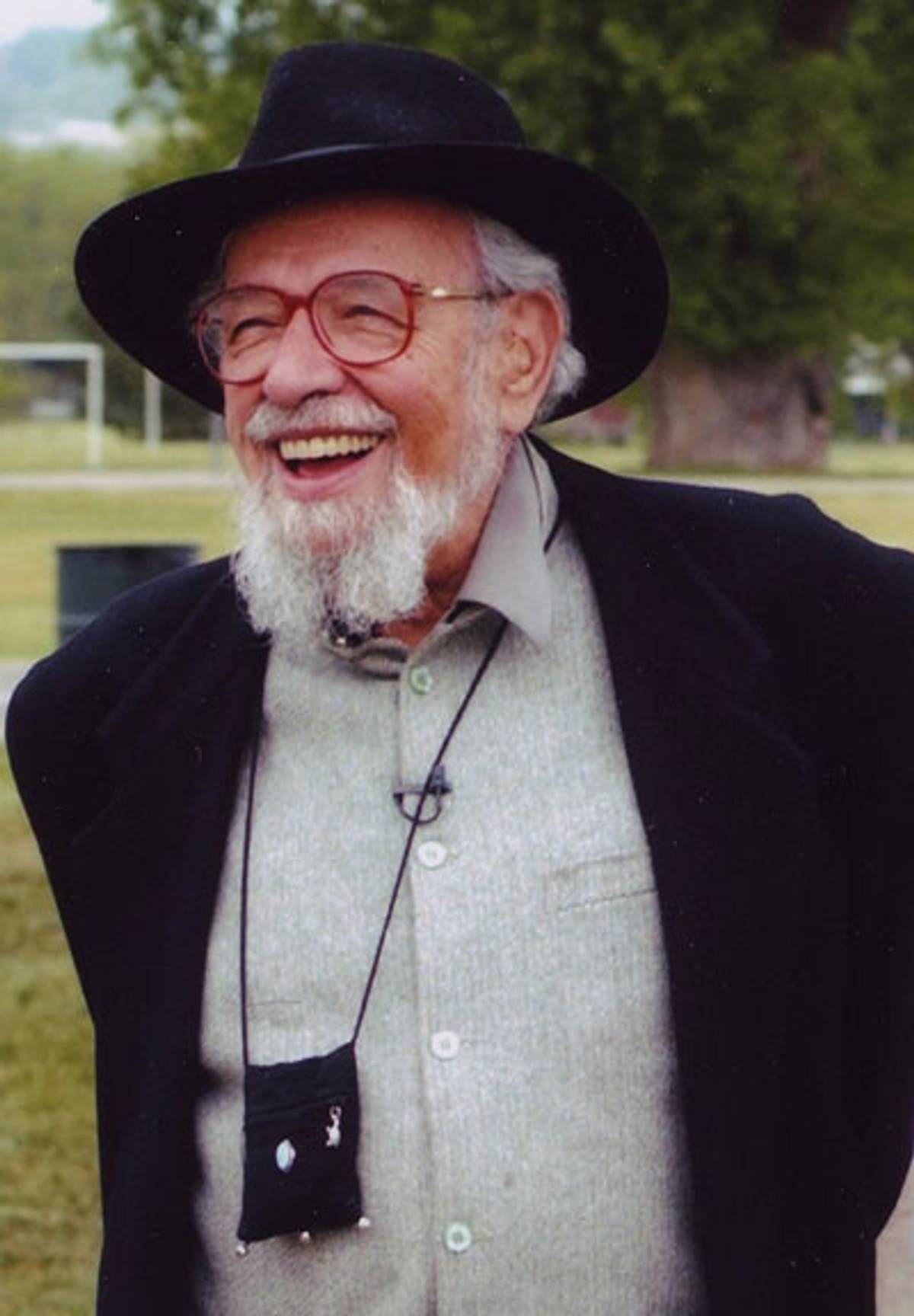

The great evangelist for Renewal, and Ingber’s teacher, was Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, affectionately known by his followers as Reb Zalman. He reinvigorated prayer by introducing chants, dance, and meditation into services. Schachter-Shalomi died in July 2014, and now, a year and a half after his death, the movement is experiencing a surge of momentum. Rabbis and congregations around the country, including Romemu, identify and affiliate with Aleph, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal. On the Aleph website there is an interactive map marked by red dots, indicating the location and contact information for Renewal communities. “If you look at that map in a few months,” said Rabbi David Evan Markus, board co-chair of Aleph, “you’re going to see dots all over the place. There’s sort of this unstable equilibrium, and we’ve reached that point where it’s going BOOM.”

The 2013 Pew Study of U.S. Jews was the first to include the Renewal movement as a distinct denomination, albeit with not sufficient data to calculate exact numbers. Although the movement is growing, serious questions remain as to whether or not Renewal can remain vibrant and innovative without its charismatic leader. Schachter-Shalomi had an inimitable perspective, one that combined a mastery of Jewish texts, learned during his Hasidic upbringing, with an appreciation for the American counterculture, that can’t easily be replicated. What is the future of this “home-grown American” Jewish movement, as Magid calls it, and will it survive without its rabbi?

Born Meshullam Zalman Schachter to a family of Belzer Hasidim in Zholkiew, Poland, in 1924, Schachter-Shalomi moved with his family to Vienna when he was 3 years old. Enrolled in a traditional yeshiva and active in a Zionist youth organization, he experienced the flourishing Jewish life in Vienna before fleeing Nazi persecution and escaping to the United States in 1941. He studied in New York under Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, and received smicha, ordination, in 1947. Schachter-Shalomi and his fellow Chabadnik, the famous musician Shlomo Carlebach, were handpicked by the Lubavitcher Rebbe to do Jewish outreach on college campuses, but soon Schachter-Shalomi’s embrace of the 1960s counterculture placed him outside the community’s mores.

Married through a Chabad matchmaker at 19—to the first of his four wives, with whom he had five of his 11 children—Schachter-Shalomi took a job as the rabbi of a congregation in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1952. By 1956 he had completed his master’s degree in psychology of religion at Boston University and taken a position at the Hillel of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, where he also taught in the religion department. In 1958, he published a guidebook on Jewish meditation and was soon experimenting more creatively with rituals and prayer. As an educator at Camp Ramah in the early 1960s, he embraced experiential education by encouraging campers to go on 24-hour meditation retreats, sew their own rainbow tallits, and write personal prayers.

For spiritual seekers who craved both authenticity and New Age values, Schachter-Shalomi had “the aura of having been born in the Europe that was destroyed,” according to Sarna. Schachter-Shalomi used “music and dance and body movement but [was] obviously also influenced by Hasidic teachings to find new ways to get people involved in prayer.” He developed an approach to prayer that he called davvenology, described by Jill Hammer, a student of Schachter-Shalomi and author of a Renewal siddur, as an ecstatic form of prayer which uses “a lot of music, a lot of joy, a lot of using the senses to create celebration.” Marcia Prager, another prominent Renewal rabbi and student of Schachter-Shalomi, recalls that Schachter-Shalomi “encouraged us to daven in Hebrew and in English—Heblish … so they weave together and intertwine within one another.”

Fearless about interfaith dialogue, Schachter-Shalomi also fostered close relationships with spiritual leaders around the world, including American Trappist monk Thomas Merton and the 14th Dalai Lama (such encounters are chronicled in Rodger Kamenetz’s classic The Jew in the Lotus). These interactions inspired Schachter-Shalomi to create unique Jewish prayer experiences that integrated elements of other forms of prayer, such as Buddhist meditation techniques and Sufi chanting. In this respect, he and his followers self-identified as the “advance scouts” of Judaism: the ones on the front lines who would experiment with Jewish ritual to determine the most suited innovations for American Judaism.

Not just a davener but an activist, Schachter-Shalomi pioneered the notion of “eco-kashrut,” which stressed that food needed to transcend the legal minutiae of traditional kashrut and address broader concerns about food ethics and environmental sustainability. Ideas like this one were put into practice at Havurat Shalom, a community founded in 1968 in Somerville, Massachusetts, by Schachter-Shalomi and peers like Arthur Waskow and Art Green. Havurat Shalom, which had a house where some members lived, became a center of Jewish prayer, spirituality, study, and experimentation, functioning as a model that inspired similar communities across the country.

Reb Zalman first encountered psychedelic drugs with Timothy Leary and later with Green, the founding dean of Hebrew College’s rabbinical school. Green recalled that in the 1960s he and Schachter-Shalomi “were practically the only people you could talk to about both psychedelic experience and Hasidic texts.” They used LSD to understand the “experience behind Jewish mystical texts,” deriving new meaning from their respective backgrounds of intense textual study.

All of these innovations amounted to what Schachter-Shalomi referred to as “Paradigm Shift Judaism,” revitalizing religion to fit the realities of contemporary American life. Some innovations, such as an inclusiveness of LGBTQ individuals, egalitarian services, the rainbow tallit, environmental celebrations of Jewish festivals, and integrating meditation and yoga into Jewish prayers, have become mainstays of liberal Judaism. Others, such as a Passover Seder that substituted inhalations of cannabis for the four cups of wine, did not survive that epoch of experimentation.

Schachter-Shalomi’s Orthodox counterparts and teachers did not approve of his innovations, and a lecture he gave titled “Kabbalah and LSD” in 1966 was the final straw for many. In the early 1970s, the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe stopped responding to letters from Schachter-Shalomi, effectively severing their “real personal relationship,” Magid said. “When the Lubavitcher Rebbe stopped writing back … [Schachter-Shalomi] basically writes back and says, I don’t know why you’re cutting me off; I’m just doing what I learned from you,” Magid said, referring to letters between the two that he recently uncovered in the late Schachter-Shalomi’s basement in Boulder, Colorado.

In 1969, Schachter-Shalomi created the Bnai Or Religious Fellowship in Philadelphia, laying the groundwork for the organization that would become Aleph, which serves as the denominational wing of the movement, in 1993. Five years later, he gave rabbinic ordination to a student, Daniel Siegel, for the first time. Bnai Or was renamed P’nai Or in 1985, and to this day there are several Renewal communities bearing this name, including the community in Philadelphia, now led by Marcia Prager. Philadelphia is also the home of Aleph’s headquarters, which has administrative staff across the United States and, according to its 2014 tax returns, has an annual budget of approximately $1.3 million.

The success of the Renewal movement aside, Schachter-Shalomi’s peers reported that he felt an acute loneliness as a result of his severed connection with Chabad and “old-school yeshiva culture.” He is said to have once called his friend Rabbi Gershon Winkler, saying, “I just need to talk Rashi with someone.”

In Romemu’s Ingber, Schachter-Shalomi found a student with whom he could talk freely. At an event in Romemu in 2011, Schachter-Shalomi said about Ingber, “I found a talmid [student]. What was so remarkable was that I didn’t have to use explanations. I could use the shorthands of the traditional language.”

Once a loose conglomeration of individuals and congregations, Renewal is now making a conscious effort to create more structure. Aleph currently lists 47 communities across the United States and beyond, including Romemu in Manhattan, Nava Tehila in Jerusalem, and Or Shalom in Vancouver.

Still, hard numbers of the movement are hard to come by. Steven M. Cohen, an American sociologist who focuses on contemporary American Jewry, estimated that Renewal Jews make up 1 percent of the American Jewish landscape. He noted that the movement lacks a denominational body to collect numbers and hasn’t outlined clear criteria for inclusion, which makes its growth difficult to assess.

While Renewal insiders are proud of the numbers of communities that affiliate with Aleph and with the growing number of students at their rabbinical school, which admitted 25 students in the last year, they also argue that Renewal’s influence can’t be counted in numbers of bodies alone.

Schachter-Shalomi hoped that Renewal would “be a virus.” According to Ingber, he hoped it would “infiltrate and infect as it were as many places as possible.” His legacy, Ingber said, “is that much to the chagrin of his students, he didn’t care about trademarking stuff. Reb Zalman was not a copyright, trademark kind of person,” even if it meant Renewal would not receive due credit.

As a movement centered around one man’s persona and charisma, Renewal is now at a critical juncture in a post-Reb Zalman era. “Everything that happens now in Renewal on some level was generated by Reb Zalman,” Magid explained. The consensus is that there is nobody who could or should take this place. “His whole upbringing was prewar Europe,” Magid added. “I think that that makes it impossible” for anyone to replace him. Like Carlebach and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, so, too, Schachter-Shalomi: These men bridged old Europe and new America, and nobody can do that anymore.

But if Schachter-Shalomi is irreplaceable, what’s in store for the movement? “Our aim isn’t to be another denomination,” said Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, co-chair of the Aleph board. Her co-chair, David Evan Markus, added that “denominationalism is very top down.” The Renewal model, he said, “is not vertical so much as it is horizontal—it’s a network,” with Aleph as its connector. Renewal Jews can be both Renewal and Reform, or Conservative, they explained, because Renewal isn’t a denomination: “You can self-identify [Renewal], and it doesn’t matter if you’re a Reform synagogue, like Rachel’s,” he emphasized, citing the fact that Barenblat leads a Reform congregation in western Massachusetts.

To Sarna, that is unrealistic. “In American religion,” Sarna said, “the great paradox is that … everybody will end up being one more denomination.” Without a seminary, an organization of congregations, and a rabbinic organization, “it’s very hard to have long-term impact,” he said. By these criteria, Aleph is well on its way toward becoming a denomination. “It’s nice to have an influence beyond the boundaries, but that doesn’t pay the bills,” said rabbi and author Jay Michaelson.

Put differently, Romemu’s Ingber explained that Renewal “has this big question of whether or not it wants to be a network, an alliance, a virus, or if it wants to take on some of the features of denominational infrastructure.” To him, the question of Renewal’s future is inextricably tied to the future of liberal Judaism as a whole. “I think that all of the liberal denominations should be under one umbrella,” he explained, “and Renewal Judaism would be folded into that.”

Another key matter of survival for the movement is whether it can continue innovating, as Schachter-Shalomi prophesied, optimistically, before his death. Creativity is the defining characteristic of Renewal, and without constant experimentation, the movement runs the risk of merely concretizing innovations from previous decades. A movement stops moving once it becomes a movement, Ingber noted, quoting his teacher. There’s an understanding within Aleph that the Renewal of 1970s should look radically different from the Renewal of the 21st century.

Even Renewal, in other words, must be renewed.

Rachel Delia Benaim is a freelance religion reporter. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, and The Diplomat, among others. Follow her on Twitter @rdbenaim. Yitzhak Bronstein is a freelance writer and traveler with a degree in philosophy.