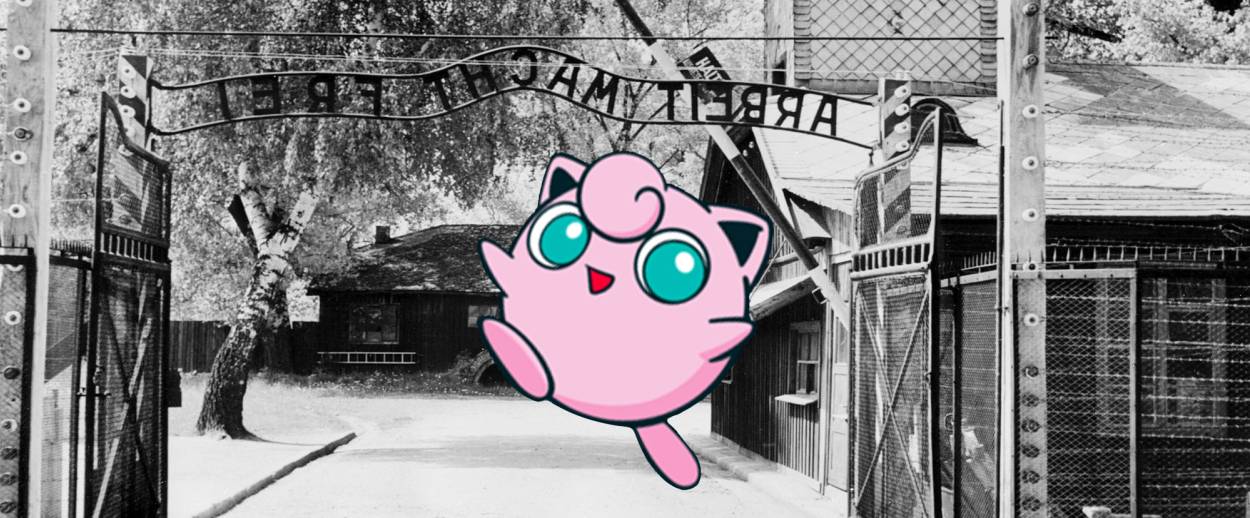

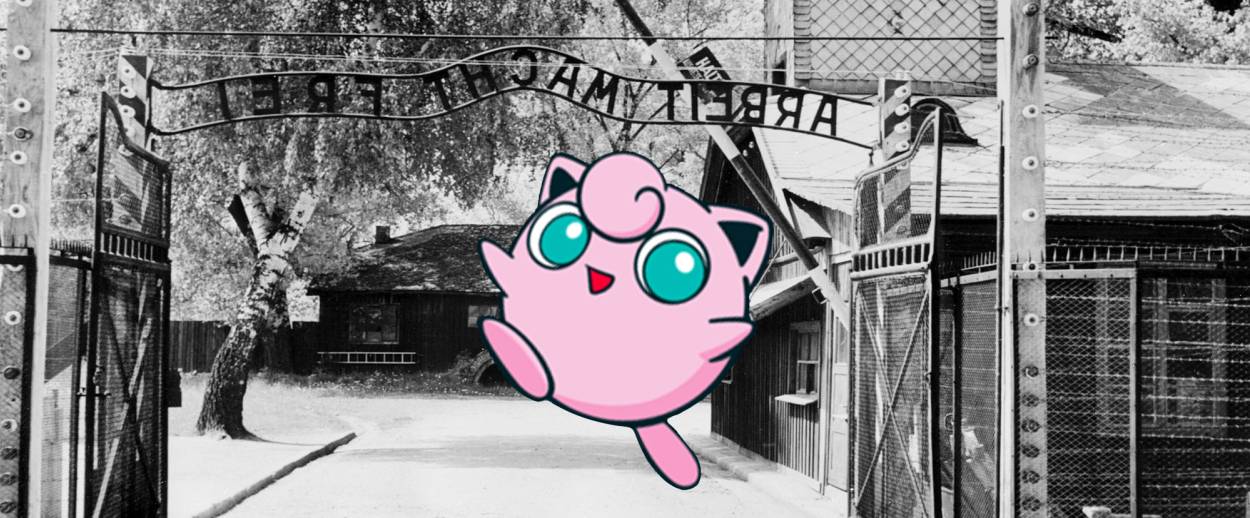

The Case for Pokémon at Auschwitz

Playing the popular game in the death camp is a celebration, not a desecration

Amid all the other signs that our civilization is galloping toward the abyss, the merchants of outrage were thrilled to report the other week that scores of young folks were once again being decadent and depraved, this time by playing the popular augmented reality game Pokémon Go at a smattering of sacred sites, Auschwitz included. Kids today! Not for the first time, however—and, Lord knows, not for the last—the dim bulbs entrusted with illuminating our culture are getting it wrong: Playing a video game at a death camp is far more reverential—and healthier—than you’d think.

To understand this rankling observation, consider Johan Huizinga. No stranger to Nazi terror—he spent the last three years of his life in a concentration camp after standing up to the Third Reich and its atrocities—the Dutch historian is primarily remembered today as the author of Homo Ludens, still the definitive book about the intensely human urge to play. It’s a slim and astonishing volume, not least because it manages to support its insights with an exhaustive list of examples drawn from different cultures and different times. At its heart is a radical argument: Play preceded culture.

Early man, Huizinga believed, emerged from his cave, looked up at the heavens, and felt the shock of the strange. Why was the sky dark one moment and brilliant the next? Why did water sometimes trickle down from the sky and sometimes not? What made the world cold, and what warmed it up again? Man didn’t know. And knowledge was just what he craved: “For Archaic man,” Huizinga wrote, “doing and daring are power, but knowing is magical power. For him all particular knowledge is sacred knowledge—esoteric and wonder-working wisdom, because any knowing is directly related to the cosmic order itself.”

What to do when you know little? Ask any 5-year-old and she’ll tell you that you simply make up rules of your own. Early man, Huizinga posited, did the same: Unable to unlock the mysteries of his universe, he made up intricate games with precise sets of rules that he could both understand and control, bringing small moments of perfection to a deeply imperfect world. Play, Huizinga concluded, was therefore not mimetic—imitating the natural order observed in the outside world—but methectic, creating order by imposing patterns of its own. “Culture arises in the form of play,” he wrote. “It is played from the very beginning. Even those activities which aim at the immediate satisfaction of vital needs—hunting, for instance—tend, in archaic society, to take on the play-form.”

It’s probably pushing it too far to claim that the mobile millennials trawling the Earth in search of Pidgey, Squirtle, and Charmander are engaging in serious culture-building. But nor is it fair to dismiss them as disdainful heathens who desecrate their civilization’s holiest sites by turning them into arenas for video-game playing. If you’ve ever played a game with as much dedication as most Pokémon Go players seem to bring to their pastime of choice, you know that mystical quiver that takes hold of you a few hours in, that heady feeling that maybe the world is just a touch bigger and more magical than you’d previously considered, that bolt of confidence that you and you alone can usher destiny on its course. That feeling is why we’ve always loved playing games; it’s also precisely the thing that’s so sorely lacking from Holocaust museums, cemeteries, national monuments, and other hallowed grounds where, to hear the bores tell it, Pokémoning should be forbidden.

The reason for this discrepancy is fairly obvious. Monuments and museums are grounds consecrating the long-concluded past; games are environments consisting exclusively of the present. In a game, the time is always now. And unlike museums and monuments, games offer not some external Archimedean point from which to consider life unfurling at a distance, but a continuous sensory engagement that makes reflection of any sort impossible. A game, like a ritual, makes you lose sense of who you are and what you’re doing, putting you in an altered state of mind that seeps out and imposes itself on the world around you.

Which is precisely why you should play Pokémon Go at Auschwitz or anywhere else. As anyone who has ever observed the listless faces of children dragged to an educational museum could attest, few experiences are more dispiriting than the forced reverence you’re expected to show when entering a site commemorating some long-ago atrocity. So what if the sun shines and the day is gorgeous and the girl you like just winked at you? This is Auschwitz, son, and as soon as you walk through its iron gates you will feel the requisite sadness or else. Such gravity on command is oppressive; it’s the reason so many of us can’t help but snicker as soon as that moment of silence begins—no sooner does the hush descend than we recall the funniest thing we’ve ever heard. When urged to bow before death, life finds a way.

Let these kids play their game, then, not even in Auschwitz, but especially there. Let them feel again that mad methectic magic Huizinga spoke about. They can’t make sense of Auschwitz, anyway; they can’t fathom what led to such brutality, can’t make sense of such hate. But they can catch a Jigglypuff and feel a burst of life whistling through the airless chambers of the factory of death. And that’s no small thing, no minor testament to the same resilience the Nazis eagerly and futilely tried to extinguish. Where better than Auschwitz to admit we’ll never have real knowledge, and where better to declare we’ll always have great games?

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.