An Early Taste of Zionism

Published 80 years ago, Palestine’s first Jewish cookbook brought politics into the kitchen, along with new ideas about Jewish food and vegetarian cuisine

“What shall I cook? This problem, the concern of housewives the world over, is particularly acute in our country. The differences in climate and the necessary adjustments arising out of these differences compel the European housewife to make many drastic changes, particularly in her cooking.”

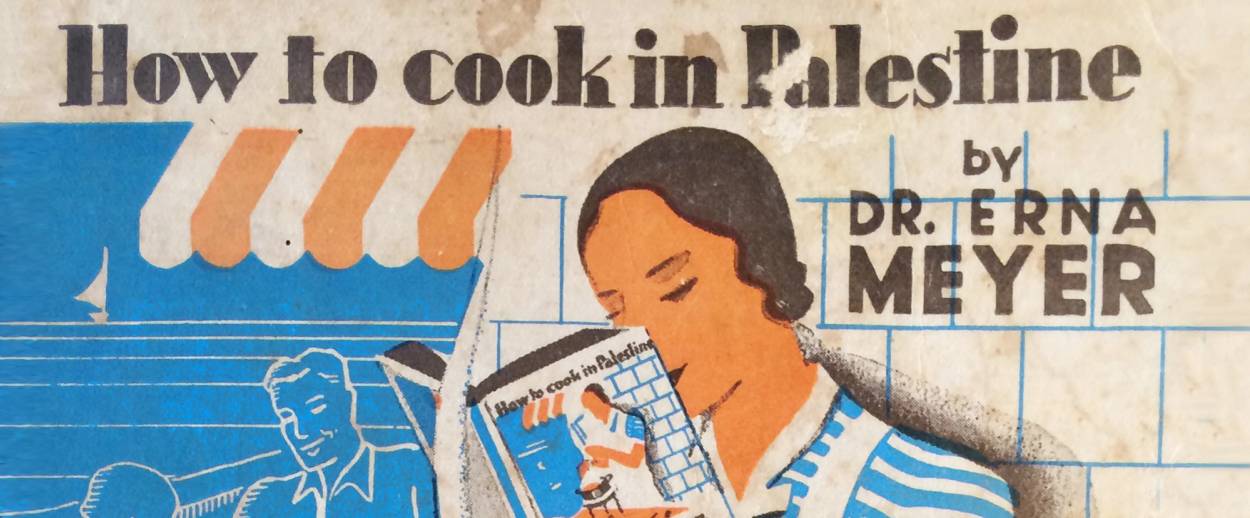

With these words, Dr. Erna Meyer introduced her cookbook, How to Cook in Palestine, which was published in Palestine in the mid-1930s in Hebrew, English, and German. “We housewives must take an attempt to free our kitchens from European customs which are not applicable to Palestine. We should wholeheartedly stand in favor of healthy Palestine cooking,” writes Meyer, urging new Jewish immigrants to Palestine to shed their European identity and reinvent themselves according to the Zionist ideology. “We should foster these ideas not merely because we are compelled to do so, but because we realize that this will help us more than anything else in becoming acclimatized to our old-new homeland.”

Meyer’s book is widely considered the first Jewish cookbook printed in Palestine during the British Mandate. Although the publication year isn’t printed inside the book, by most accounts How to Cook in Palestine came out in 1936, exactly 80 years ago (although some accounts claim 1934 or 1937). It was published in Tel Aviv by the Histadruth Nashim Zionioth, the Palestine Federation of the Women’s International Zionist Organization. Meyer was assisted by Milka Saphir, who was a nutrition and cooking teacher at the WIZO domestic-science school in Nahalat Yitzhak.

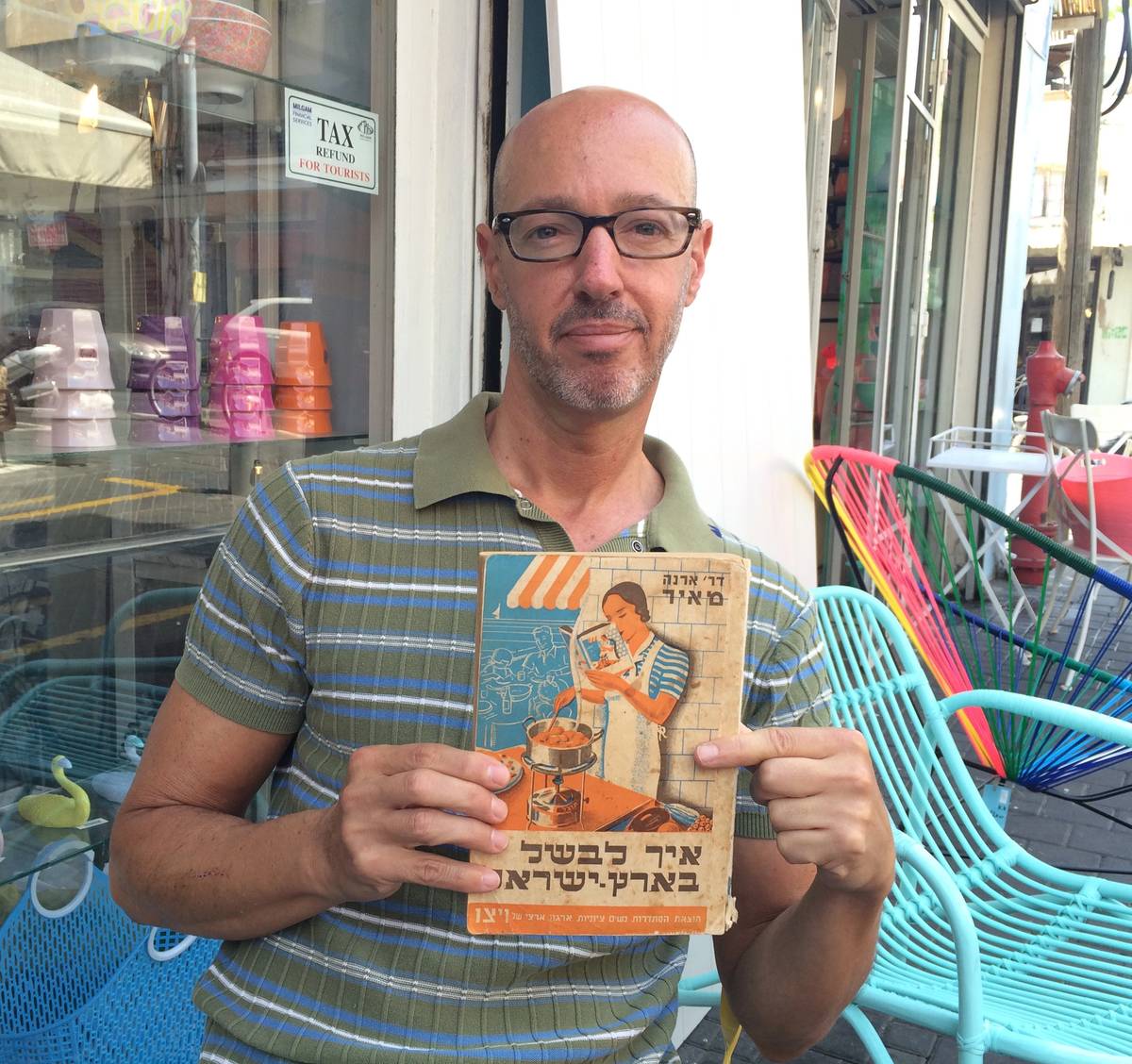

In Israel today, How to Cook in Palestine is a coveted collector’s item that does not stay long on the shelves of second-hand bookshops. It was no less popular when it was originally published: Because few cookbooks came out in Palestine in those days, this book was considered a bible to Jewish immigrant women, and Meyer was regarded their guru.

“Most of the cookbooks of the time were published by WIZO,” Gil Fanto told me. An avid collector of local nostalgia items, Fanto decided to open his collection four years ago as a private museum called Made in Eretz Israel at his home in Jaffa; he had kindly lent me his copy of Meyer’s book. “WIZO helped the women of Palestine run every aspect of their household, and, of course, cooking and nutrition were a big part of that. These books were directed exclusively to women—the housewife was a very important role in those days of Eretz Israel.”

Responding to the rise of National Socialism in Germany, many Jews fled Germany for Palestine in the 1930s. Meyer belonged to this community of relocated German Jews. Coming from one of the most modern countries in the world, this bourgeois, mostly middle-class group of immigrants had to face overwhelming lifestyle changes. Meyer tried to help immigrant women feed their families in their new underdeveloped land. Not only did these women need to cope with difficult conditions and unknown products, many of them had hired help back in Germany and didn’t even know how to cook.

“Erna Meyer was a well-known expert on domestic economy and the rationalization of the home work in Germany before she immigrated to Palestine in 1933,” wrote Viola Rautenberg-Alianov in her paper How to Cook in Palestine?—Guidebooks for German-Jewish Homemakers in Palestine (1936-1940) at the University of Hamburg. “Her cooking-book was obtainable at WIZO offices, in bookstores, and grocery shops. It includes recipes, instructions for the use of cooking equipment, as well as general articles on cooking and health. Even though published in three languages, it was mainly targeting the immigrants from Germany.”

The first chapter of How to Cook in Palestine is called “Cooking With Oil” and is dedicated to persuading housewives in Palestine to cook with vegetable oil or Kokosin instead of butter. (The latter is a local brand of butter substitute made of milk and coconut oil, which was popular at the time and became even more so in the period of austerity from 1949 to 1959.) The rationale behind this—as always—was Zionist: “The Palestinian housewife, whose duty is to support home industries, naturally buys Tnuva butter, but if for reasons of economy she cannot do so, why should the only alternative be to buy foreign butter or margarine when there are such excellent vegetable fats produced locally?” wrote Meyer.

“It was considered very important to use products that were totzeret haaretz—meaning made in Israel—and this was always stressed in the cookbooks of the time,” said Fanto. “The books were full of ads of local companies and the recipes specified what brands to use, like Assis, a company that manufactured juices, concentrates, and canned goods; Tnuva, which specialized in milk and dairy products; and Shemen oil.” How to Cook in Palestine is full of actual ads, while the same products are reflected in advertorials in Meyer’s articles and recipes—a perfect example of Zionism and capitalism going hand-in-hand.

When mentioning fats Meyer also mentions calories—but as unbelievable as it may sound today, she mentions them favorably. “In those days, fat and sugar were considered extremely healthy and ads pointed out whenever a product included these ingredients,” Fanto explained. Even though one of the objectives of cooking in Palestine in those days was piling up the calories, this book is actually a vegetarian cookbook—but not for PETA-like reasons. “Cooking suitable to the climate must place vegetables, salads, and fruits in the foreground,” Meyer explains in her introduction. “The preparation of meat and fish, being the same all the world over and obtainable in every cookery book, will not be dealt with here at all.” Elsewhere she claims that vegetarian dishes are more suitable to the climate and they should be well-seasoned in order not to taste “tasteless.”

Meyer gives special attention in her book to local vegetables such as marrow (similar to the zucchini), okra, and eggplant, giving us a glimpse into the roots of Israeli cuisine. Instead of liver, Meyer offers eggplant “liver”—a chopped eggplant dish, which tastes a lot like traditional Ashkenazi chopped liver. Eggplant “liver” was a big hit in the days of austerity, in which meat was scarce, and it can still be found in delis and supermarkets in Israel to this day.

The recipes in the book are very simple and basic; many of them are cold dishes, suited to the local climate. One example is the sandwich-cake: “Order from the baker a sandwich loaf baked in a cake tin. Cut through once or twice, spread differently colored butter or cheese spreads on the surfaces so produced, cover the outside with a similar spread and decorate as desired (it is advisable to use a cheap cheese spread, as large quantities are required for this; a thick mayonnaise may also be used).”

Indeed, saving money was of the essence considering local economic conditions, and Meyer strived to find cheap products to cook with. Therefore, there are lots of potato dishes in the book, from potato goulash to stuffed potato balls and potato noodles. Other than that, the book includes soups (including fruit soups), vegetable dishes (like eggplant with eggs, spinach pudding, and cooked sauerkraut), main dishes (like soufflés), rice/semolina dishes, salads, drinks, sandwiches, and desserts.

“Erna Meyer’s objective was to use local products and to find recipes that best suited the local weather as well as the kitchen appliances that were available in Palestine in those days,” Fanto said. “They didn’t have stoves or ovens. Instead, they cooked on kerosene burners or primus stoves. For women coming from Europe, the cooking conditions in Palestine were not easy and this book tried to make the most of what was available. That’s why most of the recipes are very easy—they didn’t have the conditions needed to cook more-complicated recipes. Baking was obviously a problem, so the book includes many recipes enabling the housewives of the time to bake cakes in a wonder pot on the primus.”

If you are wondering how a pre-Israeli cookbook could be devoid of hummus or falafel, the answer is simple: In those days, most of the Jewish population in Palestine was Ashkenazi. The big aliyah from Arab countries started after the Israeli Declaration of Independence, so until then most cookbooks had a European orientation. A few years later, newer cookbooks, with very different kinds of recipes, started to appear in Israel and influenced the creation of what we know today as modern Israeli cuisine.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.

Plain Cake

From How to Cook in Palestine

4 eggs

1 cupful of sugar

1 teaspoonful of rum

1 3/4 cupfuls (280 gr.) of semolina, mashed potatoes, or cooked and strained puree of beans (the latter cake tastes like chestnut cake)

Mix the yolks of the eggs with the sugar until creamy, stir in the other ingredients, the beaten whites of the eggs last.

Bake in well greased wonder pot for about an hour.

Cut the next day (not before) and fill generously with jam (any kind). Pour jam also over outside of cake and decorate with blanched almonds.

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.