Confronting Memories of Nazi-Occupied France

A trip with my grandmother to her French hometown revealed a complex narrative of forgotten stories, newly discovered facts, and misremembered details

Early last year, France opened its WWII police archives for the first time. More than 200,000 documents, formerly available only to select scholars and officials, became open to the public after 76 years of secrecy.

Reports soon surfaced of people leaving the archives in tears, distraught with the newfound counternarrative to what their parents and grandparents had told them about the war. With this documentation, memories, on both an individual and collective level, could be confirmed, or confronted.

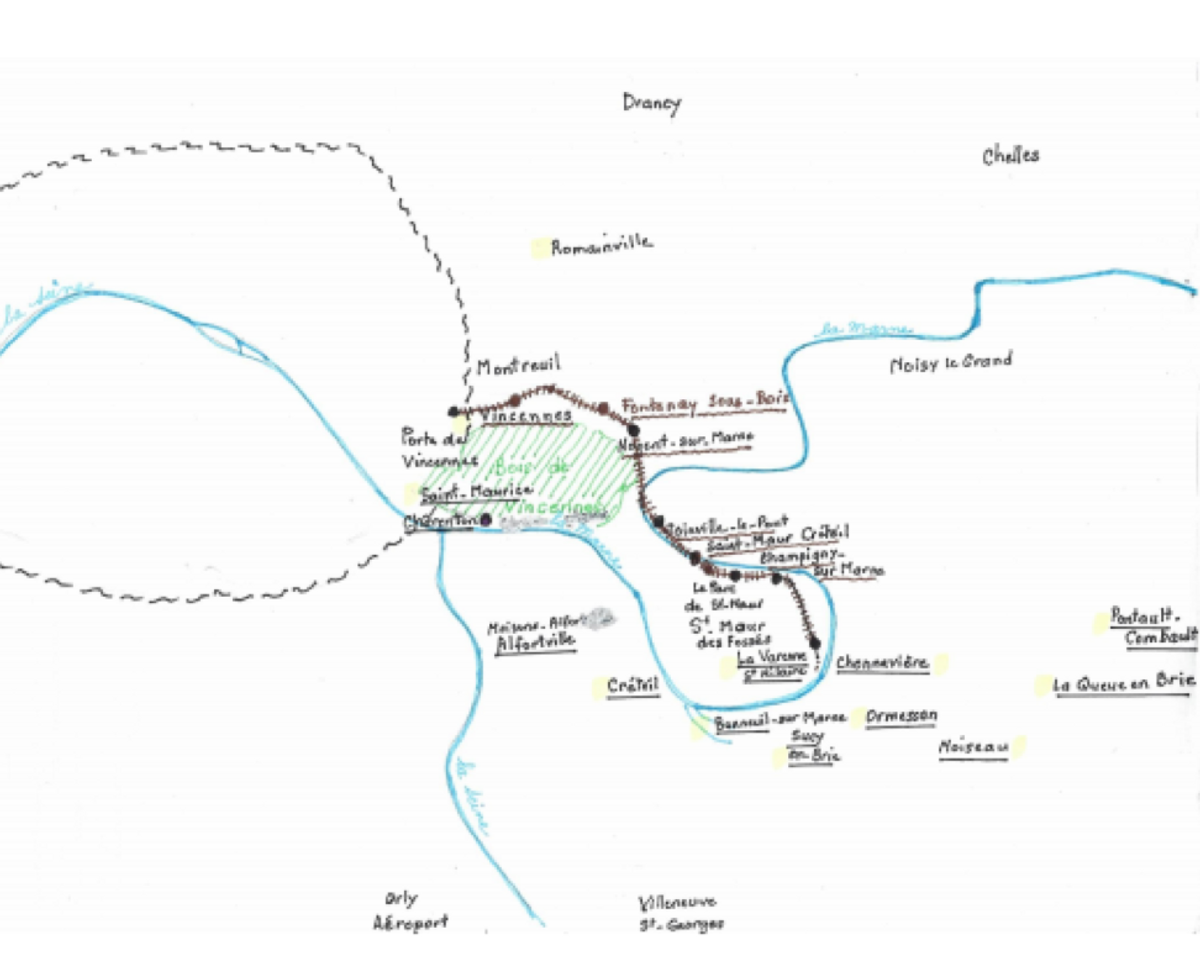

For me, the opportunity was personal. My grandmother lived just outside Paris during the war, in the town of La Varenne St.-Hilaire. The opening of the archives offered a chance for me to complete the portrait I’d begun to paint in my imagination of her family, her town, and its part in the glorious Resistance against the Nazis. And so, last summer, I traveled to France to do just this. And when I asked my grandmother to accompany me, with an infectious joy, she agreed.

La Varenne St.-Hilaire is only 10 miles from Paris. Born in a Catholic family in 1936, my grandmother—I call her Mémé— was only 4 years old when Nazi soldiers entered the area. Her town, she stated, had been relatively untouched by the atrocities of WWII. When I visited her in her home in London, Ontario, in the spring of 2016, before our trip, she said of the French police and Nazi occupiers: “They wouldn’t have done anything at all.” In fact, she continued, “They were probably instructed not to create problems.”

When I asked her to expand, Mémé warmly recalled a German officer who had approached her on the way home from primary school. “This German asked if he could hug me,” she recollected. “He explained that he had a daughter in Germany that looked just like me.” When I asked whether she hugged the officer in the end, Mémé replied that she couldn’t be sure.

While she remembered things like the request for a hug from the German officer, she couldn’t remark on the authorities’ treatment of Jewish people in her town. She recalled that there were three Jewish girls in her class. “And the teachers, in the class, they were very nice to them,” Mémé made clear. “There was one of the girls who wrote with her left hand, and the teacher defended her.” But what happened to the three girls, Mémé did not know.

She spoke to the liberation of the town with delight, describing how she tossed ripe tomatoes to the American soldiers as they descended into the valley of her town. But she couldn’t say whether there was local resistance to the Nazi occupation, or if there was any nearby fighting that may have contributed to the eventual French victory over the Nazis.

Her memories of the time had blanks, and justifiably so; she was only 8 when the Occupation ended. And, like with many children, her parents no doubt spared her some of the war’s harsher truths.

Since the liberation in August 1944, her already-constricted memories were inundated with a national narrative of underground resistance and unity. The story, perpetuated by both state and citizen, largely featured the heroic French Resistance fighters engaging in espionage and guerrilla warfare, and a few isolated incidents of villainous collaborators, lurking in alleyways and betraying their fellow townsmen. This construction of a collective memory facilitated a widespread amnesia of the varied complexities of war.

***

We were greeted at the airport with kisses and elbow squeezes by a younger image of Mémé. Jannik Coutant, Mémé’s sister and my great-aunt, still lives in France, in Pontault-Combault, a commune no more than 6 miles from La Varenne St.-Hilaire. Born in 1940, the year the Nazi Occupation began, Jannik stipulated that she could not assist us in our quest of reconstruction, as she was too young at the time to remember anything of substance. But despite her lack of memories, she would drive us to their hometown and help to arrange our reunions.

En route to La Varenne St.-Hilaire, the sisters sang songs from their youth. “Douce France, cher pays de mon enfance,” Jannik began. Sweet France, dear country of my childhood. Mémé joined in, and the two sang in unison: “Où les enfants de mon âge, ont partagé mon bonheurs” (Where the children of my aged shared my happiness).

On June 22, 1940, France declared an armistice after suffering a swift and surprising defeat at the hands of German forces. The country was divided into the occupied North, which included Paris and La Varenne St.-Hilaire, and the free South (Vichy), which collaborated openly with the Nazis. Just like the Nazi soldiers who descended this valley into La Varenne St.-Hilaire in the summer of 1940, I could glimpse the Eiffel Tower in the distance, an iron symbol of French grandeur and pride.

We crossed the bridge over the River Marne and drove through the town center. We passed the primary school Mémé attended during wartime, and then the middle school of her adolescence. After driving past the sisters’ childhood house, Jannik identified the municipal police station across the street.

“My sister,” Jannik whispered, “was a thief!”

I looked to Mémé for clarification. She met my confusion with a childlike giggle. She confided that at some point during the war, she had been brought to the police station for stealing sugar rations. “My mother turned me in!” she said. “But they were very kind to me,” she noted of the police officers.

Not far from the police station, an old friend and classmate of Mémé’s received us for afternoon tea. Throughout WWII, Nicole Brignon lived in the village adjacent to La Varenne St.-Hilaire: Joinville-le-Point. In 1949, she moved to La Varenne St.-Hilaire, where she met Mémé in high school. Brignon has, for the most part, stayed in the town since, living with her husband, André. After Mémé’s uncertainty regarding local resistance activities, I was eager to ask Brignon if she could recall any incidents of the celebrated guerrilla underground. “No,” she replied. “I’ve seen some commemorative plaques since, but I didn’t assist or see anything at the time.” Dissatisfied, I pressed forward: “What about La Marseillaise? Did you ever sing it?”

Immediately following the swift defeat of France, the Nazi occupying forces banned French citizens from singing La Marseillaise, the French national anthem. As a protest against the occupiers, in November 1940, some 3,000 Parisian high school students marched around the Arc de Triomphe while belting the anthem. The students were promptly arrested, as singing the song was declared a blatant act of resistance.

Brignon thought for a moment. “When there were alerts for the bombs, we had to climb below into the cellars to hide, and we sang songs there,” she answered, “but I don’t remember which ones.”

“We sang La Marseillaise in class!” Mémé interjected.

Brignon seemed hesitant. “Are you sure, at school?”

“I’m sure I didn’t learn it in my home,” said Mémé. “And there were others! “Philippe Henriot ment, Philippe Henriot ment, Philippe Henriot est Allemande.” Mémé sang a familiar melody set to lyrics about the lies of Philippe Henriot, the Vichy government minister for propaganda.

Jannik, who had been silent until that moment, jumped in. “No, I don’t remember those lyrics, but I remember the tune. La cucaracha, la cucaracha.”

Memory is a process of continual reconstruction, not literal recall. We reconstruct memories each time we speak, write, and express them, based on our surrounding environments. Each time we reiterate the memory, we improve, shorten, lengthen, or recast it. French philosopher and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs states in his book On Collective Memory that language is the instrument we use to comprehend our memories. Engaging in discussions is a process by which we come to an understanding of the past. “Well, I’m sure we must have sung songs, too,” assured Brignon. “But it isn’t marked in my memories.”

Memory is a process of continual reconstruction, not literal recall.

For the most part, Brignon’s answers mirrored the charming tone of Mémé’s. There were no courageous moments of French Resistance, nor were there any obscene incidents of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. Brignon had her first piano lesson during the war, a hobby that later developed into a lifelong passion. She had one encounter with a German solider, but instead of striking fear into the 5-year-old girl, he offered her chocolate. Brignon’s family even went on vacation at the start of the war. She reminisced, “My mother would take us for walks, my sister and I, holding both of our hands as we walked along the seaside.”

Neither Brignon or Mémé’s memories strongly embodied a sense of resistance or collaboration. But when it comes to WWII France, there is no word to describe someone who did not participate in either of the seemingly well-defined sides. If speech is the tool we use to comprehend memories, how can we understand events that can’t be described in existing language? These stories then, of Brignon’s first piano lessons, or Mémé’s encounter with the police, are noticeably out of place in the typical narrative of Nazi-occupied France. They suggest a level of ordinariness that, in popular culture, is not associated with the time.

The Holocaust is an object of fascination because it is seen to exist outside standard history; a supremely evil moment in a less evil timeline. But there is a danger to this framing. Hannah Arendt famously wrote in Eichmann in Jerusalem on the “banality of evil” in relation to the Holocaust. In removing WWII from the realm of what is normal, we misunderstand the actions of the perpetrators, victims, and bystanders. She wrote: “This normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.”

***

Les Archives de la Préfecture de Police, the police archives, are located in the northeastern Paris suburb of Le Pré-St.-Gervais. Behind a green-barred gate, layers of red bricks and tall glossy windows house thousands of documents dating to the 1700s. After ordering documents, officials, scholars, and now the public wait in the reading room for an archivist to call their names and hand over the files they’ve requested. On a mid-summer day, the reading room, all windows and no air conditioning, was a sauna of sweat and secrecy.

The first day in the archives was largely a learning process. But by the second day, after I had expanded my archival search to any arrests made in St.-Maur-des-Fossés, the larger district to which La Varenne St.-Hilaire belongs, I found what I was looking for.

Between 1941 and 1944, the French police arrested more than 48 individuals for reasons relating to resistance in La Varenne St.-Hilaire and the immediate surrounding area. Those arrested ranged in age from 16 to 57, with professions including boilermaker, hairdresser, and student.

In 1943, for example, the French police arrested Pierre Traverse for being a suspected “Gaullist.” The term indicates Traverse was accused of supporting Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, who at the time led this resistance movement from Britain. Others, like Jeanne Deveaux and Raoul Gaulier, were arrested for resistance activities under the guise of Communism. French police also arrested Pierre Duchesne, Eugene Albespy, Raymond Georgen, and at least seven other St.-Maur-des-Fossés residents on grounds of “sympathizing.”

Along with the suspected Gaullists, Communists, and sympathizers, locals were also arrested for possessing firearms, and participating in groups like the Jeunesses Communistes (the Young Communists) and the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (the Free Shooters and Partisans). The 48 arrests I found records for suggest not a concerted effort at resistance, but rather several, sometimes completely unconnected, acts or efforts.

Despite these varying motivations for opposition to the Occupation, following the liberation of France in August 1944, de Gaulle immediately set out to reframe wartime resistance as a national, unified movement. In his famous speech at the Hôtel de Ville on Aug. 25, 1944, de Gaulle said, “Liberated by the people of Paris with help from the armies of France, with the help and support of the whole of France, of a France which is fighting, of the only France, the real France, the eternal France.” De Gaulle and others continued to promulgate this narrative of unified resistance in the succeeding decades.

The reality of the archives demonstrated something different, more nuanced and fragmentary: hundreds of distinct, small, organizations and individuals, resisting under a broad spectrum of political, financial, and personal ideologies. While not altogether false, de Gaulle’s story oversimplified the complexity of the resistance, thereby clouding the collective memory of WWII France.

The newly released documents revealed uncoordinated, sometimes messy, efforts to thwart the French police and Nazi occupiers in La Varenne St.-Hilaire. In 1941, for example, Jacques Vayer and Marc Hennequin, ages 16 and 17 respectively, attempted to flee to Britain to join de Gaulle’s Free French. The teenage boys had made it to Cherbourg when they were caught by local police for stealing two ashtrays from the local general store. When confronted by the police, Hennequin tried to swallow a piece of paper, later revealed to be instructions regarding the purpose of their voyage to Cherbourg. The pair were promptly arrested and later found guilty of theft and possession of firearms. The boys’ attempted journey to Britain, apparently in the name of resistance, lasted less than one week.

No matter the case file, one thing was clear: The resistance movement, in fact, had been a part of life in La Varenne St.-Hilaire, even though Mémé may not have remembered or been exposed to it.

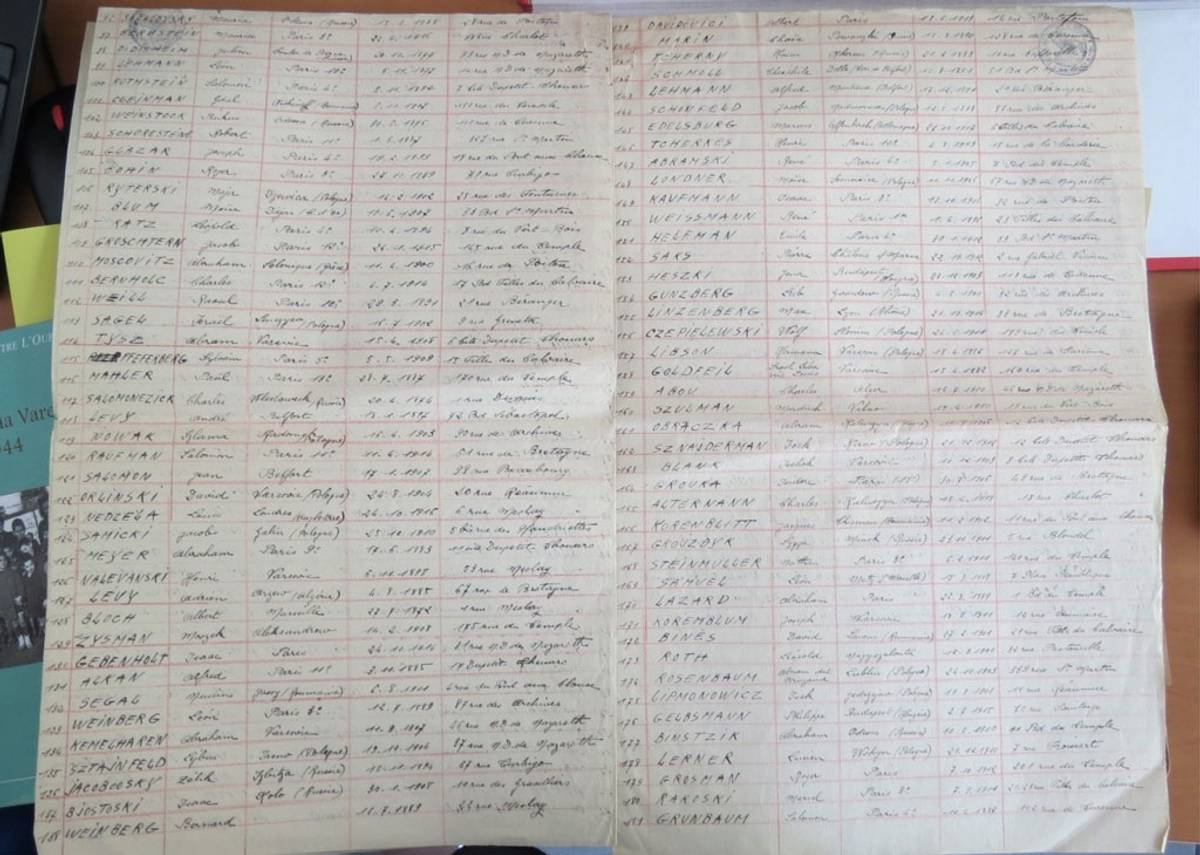

Just before leaving, I ordered dossier ID-16-7: a list of those interned at Drancy. The detention camp, located just 12 miles from Mémé’s village, was run by French police during WWII. Those detained at Drancy, later in the war, were deported to the extermination camps in the East. I requested the dossier to check Mémé’s belief that the French police and Nazi occupiers “wouldn’t have done anything at all” in her town. Although I had now confirmed that the French police were at least complicit in the arrests of local resisters, perhaps they were not complicit in any local deportations. With any luck, residents of La Varenne St.-Hilaire would not be on the list of those interned at Drancy and later deported to Auschwitz. I heard the archivist call my name, and returned to my desk in the sweltering reading room.

I don’t know what I was expecting. Perhaps another quarter-inch-thick folder, like the ones I had received while looking at the files of arrested resistance fighters. Or maybe nothing at all, just a request to broaden my search, like the one I had received on my first day of research. Instead, the archivist wheeled out a black cart, the rusted wheels squeaking with the weight of two bursting, worn boxes, each larger than a kitchen sink.

I reached into the box closest to me and grabbed the first sheet I could. The sheet was covered, from top to bottom, in names of those interned at Drancy. I looked to the next sheet — more names. Reaching deeper, each new piece of paper seemed to contain more names than the last. The room felt cold.

***

I had tried to prepare myself for our trip in advance, poring over books and articles concerning WWII France. If La Varenne St.-Hilaire was a hub of deportations, for example, I wanted to know before dragging Mémé into my journey of discovery. Although nothing could’ve prepared me for the long list of names of those deported to Auschwitz and other extermination camps I found in the archives, I’d gleaned some hints of barbarity from the book Les Orphelins de la Varenne (The Orphans of La Varenne).

One of the book’s co-authors, Michel Dluto, still lives in La Varenne St.-Hilaire and agreed to meet Mémé and me after my return to the town from Paris. Not only was Dluto expert in the history of La Varenne St.-Hilaire, he also had a personal connection to the list of names I found in the archives: His father, Charles, was among those deported and murdered.

Located on the second floor of a humble community center, Le Communauté Israelite de la Varenne St.-Maur-des-Fossés, Dluto sat at a broad wooden desk. Dluto, 77 years old, read from his father’s last letter: “I keep in good spirits, and the work doesn’t make me scared.” Dluto’s voice was unwavering. “And then he writes,” he continued, “‘I hope that Michel always does well.’”

Dluto’s father, Charles, was only 24 years old when he was taken to Drancy. Arrested in August 1941 for being Jewish, he spent seven months at the internment camp. On March 27, 1942, Charles was deported on the first convoy to Auschwitz from France. He was killed at the extermination camp three months later, on June 19, 1942.

Mémé and I sat across from Dluto, our hands folded and our eyes glued to the desk. His hands were coarse, and his stature strong. He looked up and said, “My grandmother, the mother of my mother, at only 42 years old, was deported on the sixth of July, 1942, and died at Auschwitz also.” We met his confession with silence. “So, all my life, I’ve wanted to transmit these memories.”

‘All my life, I’ve wanted to transmit these memories.’

Dluto was born in 1939 in Paris. After the French police and occupying soldiers deported his father, Dluto’s aunt, Marie, who was not Jewish, decided to protect the infant boy. She took Dluto to the countryside, not far from La Varenne St.-Hilaire, and hid him for the duration of the war.

Shortly after, Dluto and his mother moved to La Varenne St.-Hilaire permanently. Since, he has dedicated much of his life to collecting and sharing the memories of those killed during the Holocaust. He is president of Le Communauté Israelite de la Varenne St.-Maur-des-Fossés, the town’s Jewish community, as well as the Groupe St.-Maurien Contre l’Oubli, a group that informs the local citizenry about the town’s forgotten victims of the Nazi occupation. In the mid-1990s, Dluto and the group wrote Les Orphelins de la Varenne, a book about the town’s Jewish orphanage during WWII, and spearheaded the construction of a local monument to those who were deported from the town.

He also led an initiative to commemorate Emile Morel, a Catholic priest from La Varenne St.-Hilaire. During WWII, Morel helped a number of Jewish children from the area evade capture by the French police and Nazi occupiers. According to Dluto, Morel arranged for families in the countryside to shelter the children and coordinated the escapes. But when Dluto asked for Morel to be considered one of the Righteous Among the Nations, an honor bestowed to non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jewish people from extermination, Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the Holocaust, refused.

“But why?” I asked Dluto.

“Because he didn’t protect the children by bringing them to his own home. It’s stupid.” Dluto replied. “Stupid!” he repeated with fervor.

Periods of mass atrocity are complicated to explain. It’s another reason why so many people are still so fascinated with the Holocaust, the question, How could we let this happen? To learn from and create policy after a genocide requires a “larger tableau,” according to Mark Osiel, professor of law at the University of Iowa. In Mass Atrocity, Collective Memory, and the Law, Osiel writes: “In deciding how one will recount a set of brute facts, one must at least tacitly select some genre.” In creating an overarching genre for the Holocaust, however, and the resistance against it, specific actions are chosen to be remembered, while others are chosen to be forgotten.

Morel’s courageous actions do not count him as one of the Righteous Among the Nations, and therefore, he will not be remembered in these accounts. But in La Varenne St.-Hilaire, thanks to the persistence of Dluto and others, Morel is remembered for his heroism. On May 22, 2015, the community placed a plaque to commemorate the priest on the Catholic church there.

“We had an exceptional ceremony to present the plaque,” Dluto recounted, then emphasized again: “Ex-cep-tion-al.”

“And would you say that nonviolence resistance, like what Morel did, although not often celebrated, is also important to memorialize?” I asked.

“My dear,” he replied with consideration, “we can resist with love, we can resist with kindness, we can resist with words. And we can also resist with violence.”

It’s hard to say what could’ve been going through Mémé’s mind during our meeting with Dluto. Her wartime experience did not align with his. While Dluto hid from the Nazi soldiers and French police, Mémé was treated with kindness by the authorities. While he hid in the countryside, she attended school with her friends. And in the 75 years to follow, her wartime memories never included these realities of deportation or death.

Dluto’s office was filled with letters, books, plans, and documents. He explained that the building we were in now used to be a Jewish orphanage, the subject of his 1995 book.

Mémé told Dluto, “I remember we passed the building once, and my mother said to me, ‘You see the little kids that are there? They don’t have parents.’” Dluto nodded.

Remembering the three Jewish girls in her primary school, Mémé asked Dluto if perhaps they were orphans who lived in this building; she added that she wasn’t sure what happened to them during the war. Dluto said that he didn’t know their fate. He walked over to this bookshelf and rummaged through the various novels and leaflets. When he returned, he presented us the book he co-authored, the one I had researched before coming.

The book tells the story of the building we were in, and of the 29 Jewish orphans who lived there during the war. They came from all over the region, and ranged in age from 4 to 10. On July 21, 1944, three trucks arrived at the doors of the orphanage in the dead of night. Authorities under the direction of SS Capt. Aloïs Brunner forced the children onto the trucks, which next drove to Drancy, and then soon after to Auschwitz.

One of the orphans fell sick during the raid and escaped to the hospital. He evaded the trucks and survived.

I cleared my throat, “And what happened to the survivor?”

Dluto opened his flip-phone, clicked through the contacts, and slid the device across the desk.

“Here,” he urged.

***

Following our interview with Dluto, I called the number he provided and spoke with Albert Szerman. Now 80 years old, the sole survivor of the orphanage raid agreed to meet Mémé and me at Café L’Européen in Paris, two days later.

By the time we arrived, Szerman and his wife were there already.

“Well, what would you like to know?” asked Szerman.

I looked down to my notebook. My pre-drafted questions turned to a jumble of unfamiliar letters.

“You’ve prepared questions?”

“Yes … Yes … I’m not sure … It’s a huge honor to …”

“Pardon?” He interrupted.

Szerman was a commanding figure, with an authoritative voice and demeanor to match. I had carefully crafted my interview questions the night before. But now, face to face with Szerman, the questions seemed impossible to articulate.

Mémé, sensing my discomfort, initiated a conversation while I pulled myself together.

“Monsieur, where did you go to school in La Varenne?” she asked.

“No,” he replied dismissively.

In disbelief, Mémé clarified: “You weren’t at school?”

“I learned to read when I was 9, that was after the liberation. We were not at school.”

“But, I knew three girls, who were Jewish, at my school,” she disagreed.

“No, Madame, they were not at your school.”

“They weren’t at my school …?”

The memory’s skewed timeline contributed to a much larger falsehood: that the Jewish children in La Varenne continued life as normal during the occupation.

In less than 10 seconds, Szerman had thrown Mémé off. She sat back in her chair, searching her mind for the three girls. Later, we discovered that the three girls in question attended Mémé’s school after the war, and not during. Although not altogether incorrect, the memory’s skewed timeline contributed to a much larger falsehood: that the Jewish children in La Varenne continued life as normal during the occupation.

Szerman once again looked to me. “You tell me your questions. And I can reply.”

How could I ask him any questions about his childhood, when he had barely survived it? The weight of his life filled my continued silence, as I fumbled my pencil and tried to think of a question. He seemed to see my distress. His face softened, and he said, “If it is helpful for you, I can recall the details of the night of the deportation.”

Relieved, I agreed.

Szerman’s parents were deported during the Vel D’Hiv roundup, so named for the bicycle velodrome where the Jews of Paris were temporarily held. The roundup was directed by the Nazis, but carried out by the French police. On the 16th and 17th of July, 1942, French police rounded up nearly 13,000 French Jews, including Szerman’s parents, who were subsequently deported to Drancy and beyond. Szerman managed to escape the roundup that night, because he was with his nanny at the time. But now he was parentless; Szerman’s nanny sent him to live in the orphanage at La Varenne St.-Hilaire.

Szerman lived at the orphanage for two years. On the night of the deportation, July 21, 1944, hearing the rumbling of the convoy in the distance, he fell violently ill, vomiting uncontrollably out of fear. A nurse took him to the infirmary across the street to seek medical help.

From the window of the infirmary, Szerman watched the three trucks pull up to the orphanage. The orphans, Szerman’s friends, were forced out of their beds and onto the streets, still wrapped tightly in their blankets. Officers directed the children onto one of the three trucks.

“I didn’t understand why there were three trucks until much later,” Szerman explained, “I thought maybe I didn’t remember correctly … but from the window, I was sure there were three trucks.” He continued to recount that later, in university, he learned that the three trucks continued to numerous other small villages that night, picking up Jewish children from all the local boarding houses and orphanages. Two-hundred-and-sixty children in total that night, in convoy 77, were taken to Drancy, and then to Auschwitz, where there were gassed.

The next day, the nurse who saved Szerman realized that he too was supposed to be on one of those trucks. After learning that the authorities were still looking for the 29th child, she turned Szerman out onto the streets.

“She was scared,” Szerman said, without any harshness or reproach.

That morning, July 22, 1944, Solange and Henri Ardourel, local shop owners, were out early to fetch milk cans. As they walked past the infirmary, they noticed a small, sickly, boy on the sidewalk. Realizing he was probably the 29th child of interest, they took him to their shop down the street. They hid Szerman in the underground cellar of their store, where, much to his surprise, the couple was already sheltering another young Jewish child.

If sheltering one child from the local authorities was risky, sheltering two was near impossible. The couple asked one of their trusted customers for help. “They couldn’t keep both of us,” said Szerman. The customer, Szerman couldn’t remember her name, chose the other child, because Szerman, with his sickness, would be too much of a burden.

“She took the other child, and she denounced him almost immediately.” Mémé gasped, her eyes fixed on Szerman.

Throughout WWII, more than 75,000 Jews from France were deported to Nazi death camps. These deportations occurred both with and without the aid of the French police and citizens. The archives account for many of the deportations to Drancy, as well as the limitations French Jews suffered during the war years.

Despite this coordinated complicity, French leaders at first refused to apologize for France’s part in the Holocaust. In 1994, then-President François Mitterrand said: “I do not think that France is responsible. Those who are accountable for those crimes belong to an active minority who exploited the defeat [of France]. Not the republic, and not France. I’ll never ask for forgiveness in the name of France.”

Archival material and personal testimony slowly released in the 1980s and ’90s, however, contradicted Mitterrand’s 1994 claims. Only a year later, the next president of France, Jacques Chirac did apologize for France’s role in the Holocaust. Two months into office, Chirac declared in a public statement: “The criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French state. … Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners.”

Szerman told us that throughout much of his adulthood, not many people asked about his experiences. But in the past two decades especially, this has changed. “It’s because our grandchildren are the ones who are asking questions,” he said.

His testimony not only confirmed the lists of names from the archives but also painted a larger picture of what occurred in La Varenne St.-Hilaire during WWII. Mémé could not remember these events because she did not experience them. Szerman and Mémé, living in the same town, only two blocks away from one another, had two completely different types of childhoods.

Mémé looked to her cup, and then to Szerman. Her hazel eyes widening, she asked him: “Do you think the nature of man is good or bad?”

***

Like any good story, WWII France has a beginning, middle, and end.

For Mémé, the story ends with the memory of tossing tomatoes to the American liberators. For Szerman, the story ends with his rescue. For France, as a whole though, the ending is less clear.

After the liberation of France in August 1944, the nation’s fury turned to collaborators. In a frenzy of anger and shame, more than 10,000 suspected collaborators were killed. Women accused of la collaboration horizantale, having relations with a German, were publicly humiliated in town squares. The lady who took and denounced the other Jewish child sheltered in the Ardourels’ basement was among these women. She, along with other female collaborators from La Varenne St.-Hilaire, was taken to Chennevières-sur-Marne, a neighboring village, where their heads were shaved, and then they were shot.

Charles de Gaulle put a stop to the ad-hoc tumult of revenge and instituted judicial processes that would prosecute only a select few French citizens who had collaborated with the Germans during the war. In Moralizing States and the Ethnography of the Present, Sally Falk Moore writes that formal trials and state-led commemorations serve to remove an event from “the category of debatable.”

By the 1950s, the collaborators were largely forgotten. An image of wartime France emerged: a bright and shiny nation of resisters, partisans, and heroes who stood against Nazi tyranny. Perpetuated by the leaders, and willingly accepted by the people, this altered memory of WWII became embedded in the historical narrative of wartime France, both within and outside the country. In this image, there was no gray area. One was either a resister or a collaborator, and the collaborators had already been punished.

Simplifying this complex period of divisions into two sides, however, devalues the reality and possibility for future healing. In Mass Atrocity, Collective Memory, and the Law, Osiel writes: “When the event has been deeply divisive for a society … its memory will late evoke the same disagreements.” In questioning the national narrative, the collective memory, and even our own individual recollections, we seek to better understand and learn from the complexities, and atrocities, of our past.

Albert Szerman lost his faith in all religion long ago. But for him, engaging in discussions like these and transmitting his testimony is holy. “It is something I consider sacred,” he said, as we departed from the café. “Not in a religious context, but it is sacred that you and your grandmother are here.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Clare Church is a researcher and political writer based in Canada.