‘I’d Like to Become a Bird’

My great-great-grandmother’s letters—in Ladino—paint a portrait of the Sephardic community on the Isle of Rhodes, moments before it was destroyed in the Holocaust

Until my early adulthood, I had no family names or faces to connect with the Holocaust. I always assumed that, on my father’s side, any members of his extended Lithuanian family who didn’t manage to escape their shtetls for America or elsewhere had become victims of the Nazis. Unexpectedly, though, the first time I had confirmation in writing about my family’s connection to the Holocaust came from my mother’s side of the family—the Sephardic side.

As I was sifting through some family memorabilia in my parents’ Virginia home about 15 years ago, I found a typed document in Italian, dated 1964 and bearing two official seals and signatures. My knowledge of Italian was limited to vocabulary recalled from high school Latin, but enough words jumped out at me for an understanding to emerge: “ALHADEFF REBECCA…RODI…1944…deportata in Germania … in campo di concentramento.”

Like most American kids, the mainstream Holocaust narratives that I had been exposed to during my childhood and teen years focused on Eastern Europe. Despite plentiful religious school and youth-group commemorations of the Shoah, I had no comprehension whatsoever that Sephardic Jews in the Balkans and along the Mediterranean experienced many of the same atrocities as Ashkenazi Jews in countries like Germany and Poland. I had never heard of Salonica, the northern Greek city whose vibrant prewar Jewish population of 50,000 was reduced to fewer than 2,000 people. And I was woefully ignorant of the fate of the Jews on the Isle of Rhodes, a historic community reduced to 151 survivors after the war.

That piece of paper I found in my early 20s was the beginning of my search into what happened to Rebecca Alhadeff, my great-great-grandmother, known in the family as Rivca. I now know that the document was a form, issued by the Italian consulate and signed by the president of Rhodes’ Jewish community, in response to restitution claims by Rivca’s youngest son, Abner Leon. This document, along with two photographs and a Yad Vashem testimonial about her death, was the entire basis of my knowledge of Rivca for many years.

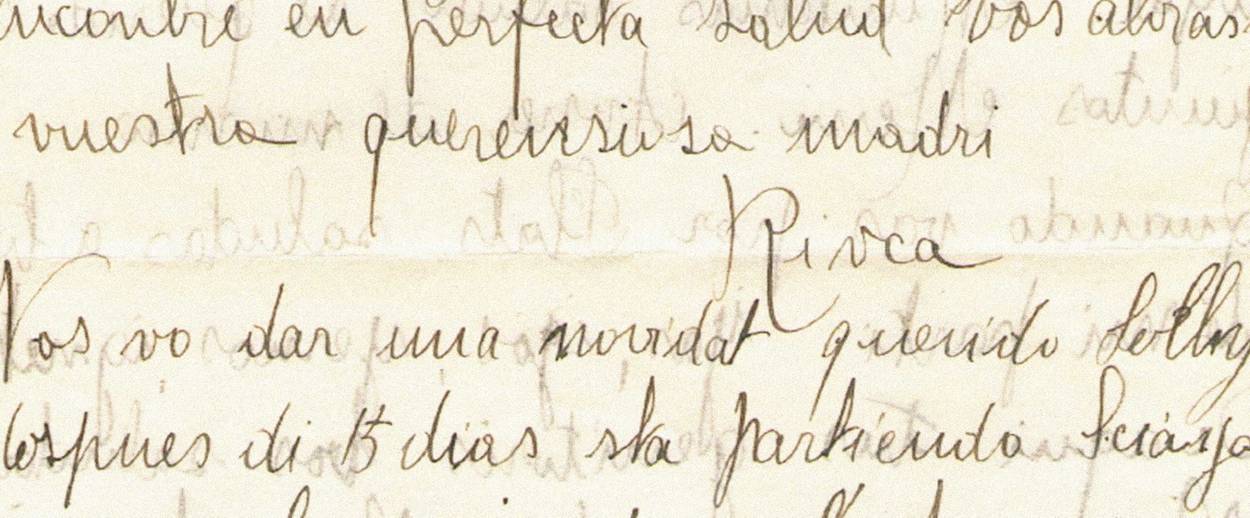

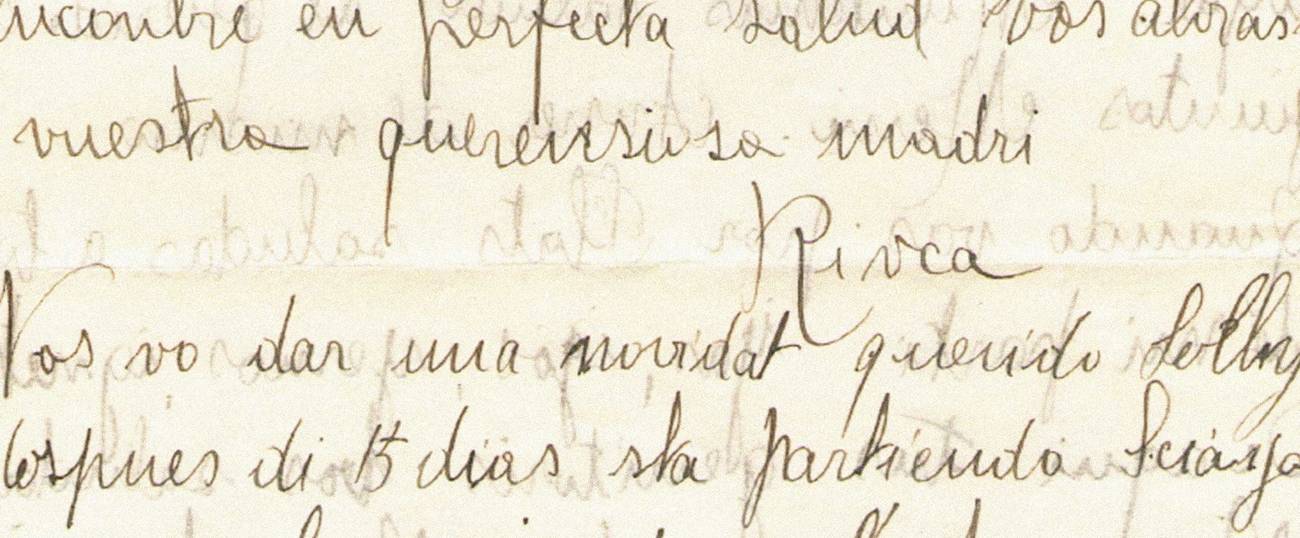

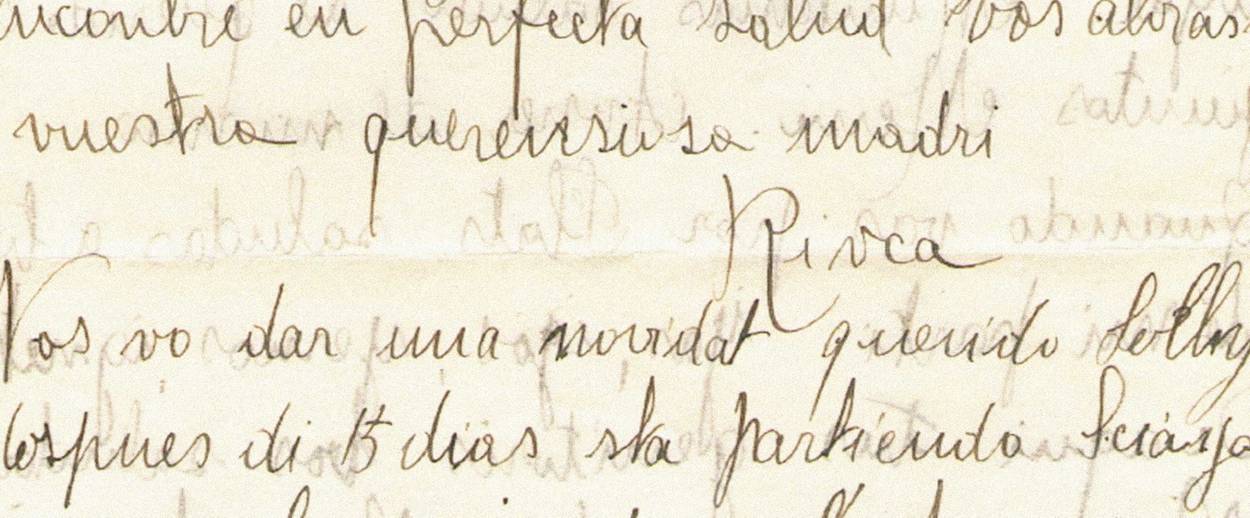

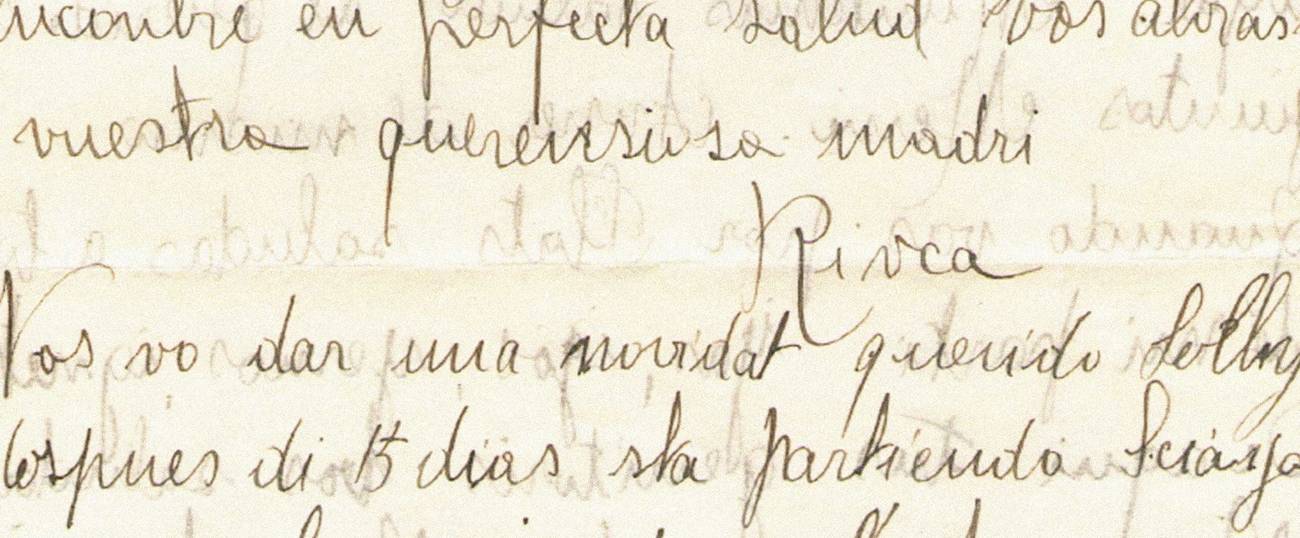

But two years ago, while emailing with a great-aunt in Capetown about my ongoing genealogical research, I found out that she possessed a few handwritten letters in Ladino that had been sent to her mother during the war. The letters’ author was my great-great-grandmother Rivca, who was born in 1870 and died at Auschwitz in 1944. Sent from the Italian-occupied island of Rhodes to British colonial Africa in the spring of 1940, the letters brim with domestic details, humor, blessings, and salutations. Life on the island, at that point, was mostly fine.

My great-aunt in Capetown sent me scanned versions of Rivca’s correspondence last year, and I have since acquired comprehensive transcriptions and translations of each letter via Emily Thompson, a Seattle-based professional translator of Ladino and Spanish. The correspondence constitutes the only remaining trace of Rivca’s voice, as well as a relatively rare window into a Sephardic woman’s perspective during the war.

In her lifetime, Rivca had witnessed power change hands several times on Rhodes. For centuries, conquerors ranging from Crusader knights to the Ottoman Turks and modern Italy had held sway over the island, which was prized as a strategic base for seafaring in the Mediterranean. For the most part, Rhodes’ Jews, who traced their roots to antiquity, were allowed to live in peace according to their religious traditions throughout these transitions of ruling powers. They populated a corner of the island known as La Juderia, the Jewish quarter in the old town of Rhodes. The 1912 Italian census listed 4,290 Jews living on the island.

The correspondence constitutes the only remaining trace of Rivca’s voice, as well as a relatively rare window onto a Sephardic woman’s perspective during the war.

To better understand the circumstances in which Rivca wrote her letters, I delved into the history of Italy’s colonial rule over Rhodes. Italy had wrested control of Rhodes from the Ottomans in 1912, and its colonial rule over the Dodecanese islands became official under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. According to Aron Rodrigue, a Stanford scholar who is currently writing a history of Rhodes’ Jews before the Holocaust, Italian rule over the island was seen as a “benevolent” enterprise under Gov. Mario Lago, and Jews could even obtain a form of Italian citizenship.

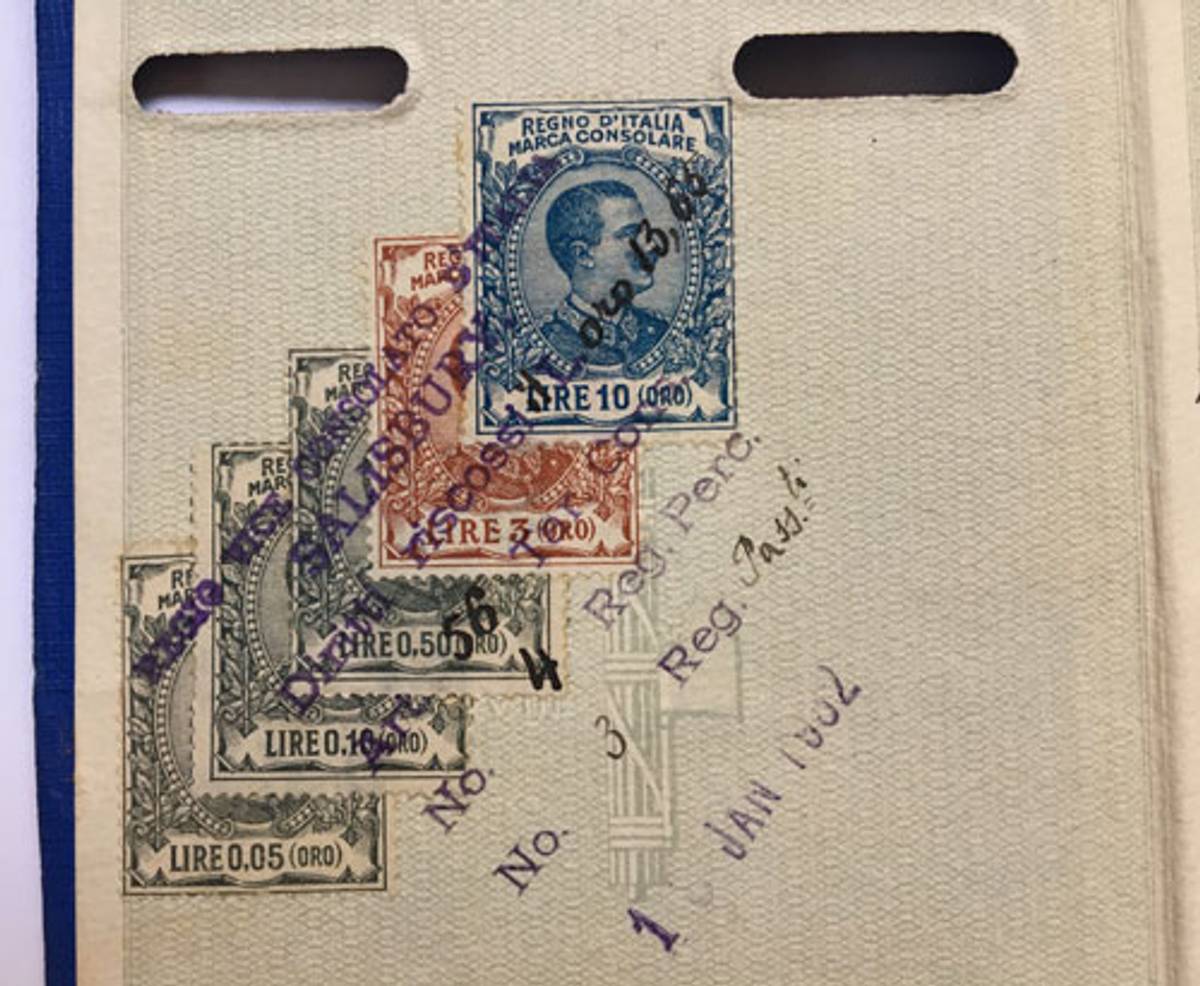

After reading one of Rodrigue’s articles, I pulled out my great-grandmother Estrella’s Italian passport, one of my prized family documents. The blue-covered passport was issued in 1932 by the Italian consulate in Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe), the British Crown Colony where Estrella was raising her family at the time. Among other things, it lists Estrella’s professione as casalinga (housewife) and her height as 1.61 meters. The passport also includes a photograph of her in a chic post-flapper bob, though the picture is partially obscured by the consulate’s eagle stamp (one of the prominent symbols of fascism).

Why did my Rhodes-born great-grandmother, a Sephardic Jew who had immigrated to southern Africa a decade prior, decide to use her birthplace’s colonial status to acquire Italian citizenship in 1932? I think this decision shows the allure of affiliating with a strong European nation-state, an understandably appealing option for Jewish citizens who had been striving for equal rights and social acceptance in Europe since the Emancipation era. Rodrigue also points that, from a practical perspective, the Jews who did not become naturalized citizens in Rhodesia needed official papers of some kind, and the Italian documents were Estrella’s only option.

Though only two decades long, the period of Italianization had a profoundly deep impact on Rhodes’ Jewish community: Besides the option to adopt Italian identity, as Estrella did, many of Rhodes’ Jewish inhabitants also adopted aspects of Italian culture, including the language, music, and participation in fascist youth movements. Rhodesli descendants in Africa and North America have told me that for many years after leaving the island, their older relatives enjoyed putting on opera music and singing along in Italian.

The relatively peaceful state of existence under Italian rule came to a halt, however, by the late 1930s, when a switch in colonial administrators brought drastic changes to daily life for the Jews on Rhodes. The Italian Racial Laws (leggi razziali) passed by Mussolini’s government in 1938 imposed increasingly stringent measures upon Jews living in mainland Italy as well as its colonies. The laws forbade circumcision, ritual slaughter, and gathering in synagogues; Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend state schools.

This was the foreboding political context leading up to Rivca’s letters in the spring of 1940, yet her acknowledgment of any change in living conditions or civil liberties is minimal. The only real reference I can find—and it is rather oblique—is an offhand comment: Ya savis querida Mari como es aqui estos dias. “You already know, dear Marie, how it is here these days.” Was Rivca genuinely unconcerned because she had seen so many other rulers come and go? Did she limit her expression of anxiety about como es aqui (how it is here) in order to keep up a happy appearance for her new daughter-in-law? Or, perhaps she was concerned that wartime censors might cancel any letters that referred negatively to Italian rule.

All eight of Rivca’s children had left Rhodes for Africa by the late 1930s, part of the waves of emigration that had started in the first decade of the 20th century. Her oldest son, Behor Samuel (known in the family as B.S.), was one of the earliest Sephardic immigrants to colonial Rhodesia, arriving in 1908. He quickly established business ventures in mining, farming, and real estate. B.S. leveraged his considerable wealth to help arrange for Rhodesli Jews to immigrate to Africa during the 1920s and ’30s, including one last boat at the start of WWII. To his dismay, however, a last-ditch effort could not persuade his own mother, a widow whose winemaker husband, Shmuel Leon, had died in 1926, to leave the island and join her children in Africa. Rivca’s mind was made up: She would stay in La Juderia, come what may.

Rivca’s reluctance to move to Rhodesia before the war may have been based on her one documented visit to southern Africa in the late 1920s. According to family sources, she arrived around 1927, soon after her husband died, and stayed for about two years. She spent her time with her youngest daughter Estrella, son-in-law Haim, and their twin daughters; I possess one undated photograph of Rivca with the twins on some kind of boat. Apparently, Rivca did not like that her children’s town lacked proper religious amenities such as a kosher butcher. She sailed back to Rhodes by 1930, probably accompanied by Estrella.

Already knowing how the story ends, I forced myself to find more facts about what happened to Rhodes during the rest of the war, after Rivca had sent off her letters in 1940. As in previous eras, the island’s location in the Mediterranean, along with its airfields, again made it a desirable strategic property. Writing in his Memoirs of the Second World War, Winston Churchill expressed his chagrin that he could not convince his American military partners of the need for a sweeping Dodecanese campaign: “It seemed to me a rebuff to fortune not to pick up these treasures. The command of the Aegean by air and by sea was within our reach.” Unsupported by an Allied campaign, Rhodes fell quickly to the Germans in the fall of 1943.

The following year, in July 1944, Gestapo forces rounded up the Jews of Rhodes along with a small group from the neighboring island of Kos. Forced onto boats, they were taken to Athens and the transit camp of Haidari, and eventually arrived at Auschwitz on the final transport train out of Greece. Of the 1,651 Rhodesli Jews who were deported, 151 survived—a cataclysmic devastation of one of the world’s oldest Sephardic communities.

Si cheria escrevir todo querida Mari cheria chi encera un journal, Rivca wrote. “If I wanted to write down everything, dear Marie, I would need a whole journal.”

Rivca’s letters record the moment just before the arc of history bent toward shadow and destruction for the Jews of Rhodes. Even with the anti-Jewish laws and the war intensifying on mainland Europe, life on Rhodes was proceeding somewhat normally. Despite the sizable emigrations of the previous decades, Rivca was still surrounded by family and friends in La Juderia, including her favorite brother, Mussani Alhadeff, a shopkeeper, and his wife and children. In every letter, she names the many relatives who join her in sending their greetings over to Africa.

‘If I wanted to write down everything, dear Marie, I would need a whole journal.’

My family sources have told me that during the war, a young cousin named Rosa Hanan lived with Rivca in her house on Via de la Eskola. In fact, Rivca dictated her letters to Rosa, who wrote them down in her looping script, using Latin letters rather than the right-to-left soletreo handwriting of Sephardic Jews. Occasionally, Rosa interjects her voice into the letters and relays questions or greetings to the recipients. The correspondence thus weaves the voices of two Jewish women, one older and one much younger, as they lived through the war together. (Rosa ultimately survived the concentration camps, married another Holocaust survivor, and settled in Rome. I met her in an emotional Skype conversation last year.)

Marriage—its joyful occurrence for her son Solomon in April 1940, contrasted with the ongoing bachelorhood of her sons B.S. and Abner—is Rivca’s main topic of discussion. Addressing herself in four of the letters to her new daughter-in-law Marie, who left Rhodes for the Belgian Congo on the last boat out of the island before the war, Rivca repeatedly expresses her joy at the union and bestows blessings upon the newlyweds: Ivas agaj viejos con todos los deseos compartidos amen—“May you grow old with all your wishes fulfilled, amen.” Though unable to attend the simcha in person, Rivca celebrated the wedding from afar with her friends on Rhodes. She boasts to Marie that 200 people attended the magnificent boda (wedding celebration) that she hosted in the couple’s honor.

Echoing anxious Jewish mothers throughout time, Rivca also uses the space of her letters to chide Solomon and Abner for not writing frequently enough. She calls them timbelico, a Ladino word for lazy (though it uses the diminutive form, expressing endearment), and employs a popular Ladino saying to encourage them to correspond with her more often: El querer es poder, or “Where there’s a will, there’s a way!” She implores Abner especially, No saves che la sodisfaction di una madri es las letteras buenas de los ijos—“You don’t realize the satisfaction it gives a mother to read happy letters from her children.”

Much more worrying than their lack of communication, though, is the fact that Abner and “Buhoraci,” as she calls her beloved oldest son, Behor, are both still single. In the letter dated May 9, 1940, she declares to Marie: “When we marry off our dear Buhoraci, we’ll have a month of wedding celebrations. God willing, we’ll see that happy day in all our lives, amen. Because this is my greatest desire.” Writing to Abner, Rivca promises to make him a boda just as impressive as the one she made for Solomon, if only he will find himself a wife. As it happens, despite her agitation on the subject, three of her five sons (B.S., Abner, and a middle son named Haim) never married.

Reading the letters over and over again, I comb through the Ladino originals and the English translations for clues to Rivca’s personality and inner life. Her religious outlook is clear, as she frequently invokes “Dio” and punctuates many sentences with “amen.” I am especially struck by the stark difference in tone between Rivca’s notes to Marie and her one letter to Abner. With her new daughter-in-law, Rivca is buoyant and positive about her situation, affirming that yo esto muy buena—“I am doing very well.” She is curious, pressing Marie for details about the wedding in Salisbury: “Tell me more, everything about that day, I’m impatiently awaiting the news.” She also asks Marie about which other Jews are living in Bindura, the mining town where the couple settled briefly after their wedding.

Only in her letter to Abner, dated May 25, 1940, does Rivca betray any sense of wistfulness that she has stayed behind on the island: Y ansi passamos la vida che mi topo tanto lescios de vosotros. “And so our lives are passing by and I find myself so far away from you all.” A few lines later, she shares a heartbreaking confession that brings me to tears: Mi cheria aser un pasciaro i bevir serca di vosotros. Ma ya me ise vieja i no es possivle di aser estos camminos de muevo. “I’d like to become a bird and live near you. But I’ve grown old already and I can no longer turn onto a new path.” Here, it seems, Rivca betrays her true feelings to her youngest son: She has made her choice to stay and is now trapped on the “path,” which—we now know—will lead to deportation to Athens and then Auschwitz in just over four years’ time.

‘I’d like to become a bird and live near you. But I’ve grown old already and I can no longer turn onto a new path.’

Rivca’s grandchildren, who now have grandchildren of their own, have told me that despite her anxieties, Rivca remained resolute during the war. During the British bombings of Rhodes in 1944, all of the Jews in La Juderia would leave their neighborhood and run to the other side of the island. Rivca, however, refused to flee the area and insisted on staying in her house. Bombs fell on structures right across the street. One hit the Alliance Israélite Universelle school where her daughter Estrella had taught French briefly in the early 1920s; another destroyed the Kahal Grande synagogue, a centuries-old worship space around the corner from her house.

But no bombs fell on Rivca’s home. It miraculously stayed intact, surviving the war even when its owner could not.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, Solomon and Abner Leon, Rivca’s adored and scolded timbelicos, would begin the legal process of requesting Holocaust restitution, which eventually resulted in their reclamation of the Leon house in La Juderia; in the late 1990s, I would discover the Italian letter sent to Abner in June of 1964, which confirmed Rivca’s deportation in July of 1944; in 2006, I would visit the family’s house, which still stands on a quiet street in La Juderia; and in 2017, I would read the correspondence that Rivca spoke aloud to young Rosa while sitting together in that house in 1940, the Ladino language flowing between them as the world beyond marched inexorably toward war.

This past May I visited the Ladineros, a Seattle group that meets weekly downtown to read Ladino texts, debate the language and its history, and talk about Sephardic culture. I had provided one of Rivca’s letters to be discussed during the class. Settling in with coffee and cookies, we went around the room so that each participant could have a turn reading a short paragraph from the letter and translating it. Isaac Azose, the group’s coordinator, who is also a retired cantor of great distinction, provided occasional corrections and thumbed through his pile of dictionaries to search for words of questionable origin or meaning.

The class is mainly composed of older members of Seattle’s Sephardic community, descendants of Jews who emigrated from Rhodes and Turkey in the early 20th century. Their parents and grandparents are the ones who managed to leave in time, overcoming the combined forces of war, global upheaval, and immigration quotas to get to America and build new lives. (Rivca made an observation about the exodus to America in her May 22, 1940, letter to Marie, which was the one I selected to read with the class: Lo chi esto mirando chi no va chidar viejos en Rodis todos si estan yendo a l’America, she wrote. “What I’m seeing is that there will be no more old people in Rhodes, they are all leaving for America.”)

As I sat and listened to the Ladineros’ renderings of Rivca’s letter, hearing her voice through their voices, I thought about how my great-great-grandparents were cousins with their relatives back on Rhodes, how Rivca might have stood in line at the communal bakery chatting with one of their grandmothers, how her husband, Shmuel, might have served raki to one of their grandfathers in his café.

I looked around the room at these Seattleites who still speak the musical mother tongue of Sephardic Jews. These are my substitute Sephardic grandparents. If 20th-century history had not taken its particular course, I might have grown up in La Juderia down the street from them. If my Leon forebears had decided to immigrate to America rather than Africa, I might have been raised in Seattle’s Seward Park neighborhood and gone to school with their grandchildren. Instead, I grew up in central Virginia at a double remove from Rhodes: far from the tight-knit community of Rhodesli immigrants in Zimbabwe, where my mother and her sisters attended religious school at the Sephardi Hebrew Congregation; and even further from the picturesque Mediterranean island that nurtured generations of Jews, until time so tragically ran out.

‘There will be no more old people in Rhodes, they are all leaving for America.’

I can’t help considering the historical “what ifs” concerning Rhodes’ Jews. What if Rivca had agreed to let her beloved “Buhoraci” take her back with him to Africa at the beginning of the war? What if Churchill’s dream of a Dodecanese campaign had succeeded? What if the trains had stopped running from Athens to Auschwitz in August of 1944, just before the Jews of Rhodes and Kos arrived? If any of these situations had been otherwise, Rivca might have “become a bird,” surviving the war, making it to Africa, and living out the rest of her life among her many children and grandchildren.

On my one visit to Rhodes, in the late spring of 2006, I visited the Holocaust memorial in Martyrs Square, located in La Juderia. An exact replica of the six-sided black marble memorial now stands in the courtyard of Seattle’s Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, the synagogue founded by Rhodesli Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century. This summer, the congregation will present its annual program commemorating the July 1944 deportation of Rhodes’ and Kos’ Jewish populations. In Seattle and in many other cities around the world where Rhodesli descendants now live—Brussels, Capetown, Buenos Aires, Los Angeles—memorializing is central to maintaining a connection with Rhodes. These Jews are consciously creating what Rodrigue calls “an island of memory” as part of their Sephardic identity.

For me, deciding how I will relate to Rhodes means figuring out the balance between mourning and celebrating. I must find ways to make meaning of my enormous sense of loss without being completely overwhelmed by it. One way I do so is to tell my children stories about the tiny island in the Mediterranean where their family lived a long time ago. I describe their ancestor Shmuel, who would fall asleep riding his donkey back from the vineyard at night. I show them pictures of the giant Crusader walls and gates that mix with Ottoman minarets in the town’s skyline. I tell them we will all visit the island one day and find the house where Rivca lived.

Another way to make meaning, as hard as it may be sometimes, is to reread Rivca’s letters from the spring of 1940. Like other Holocaust-era letters, they are marked by date and place, and they tell the story of people caught in the crosshairs of forces larger than themselves. Unlike other letters, Rivca’s correspondence belongs to my family’s narrative, casting an irrevocable shadow because of her death, but also shedding light on her life.

Hannah S. Pressman is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter, a memoir connecting her Sephardic family history to explorations of American Jewish identity.