The Best Jewish Children’s Books of 2017

Let the last-minute Hanukkah shopping commence!

If there’s been a trend in this year’s crop of Jewish children’s books, it’s diversity. Yay for depictions of Jews as a) not all white and Ashkenazi, and b) enmeshed in and part of a multicultural world in which Jewishness is only one of a character’s multiple identities.

And yay to publishers looking beyond the Holocaust and the shtetl. This year gave us one terrific Holocaust book: the memoir Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz by Michael Bornstein and Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, which is appropriate for readers 10-adult. But Holocaust books do not make for festive Hanukkah gift-giving; my goal with this list is to encourage kids and teenagers to associate Jewishness with more than genocide. Buy the best Holocaust books. They are important. But buy them for Tisha B’Av, Tzom Gedalia, or a random Wednesday. Buy the books on this list—there are 18 of them: chai!—because they will cause young readers delight.

BOARD BOOK

Sammy Spider’s Hanukkah Colors by Sylvia Rouss, illustrated by Katherine Janus Kahn. It’s Sammy Spider. It’s a board book. What else do you need to know? (Other than the fact that Mr. Shapiro has a great ’70s pornstache, and how did I never notice?) (Ages 0-2)

PICTURE BOOKS

We’ve already discussed the beautifully illustrated, soothing Yaffa and Fatima Shalom, Salaam. Here are some additional winners:

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: The Case of RBG vs. Inequality by Jonah Winter, illustrated by Stacey Innerst. Holy moly, is this book gorgeous. Rendered in gouache, ink, and Photoshop, it looks super-painterly without being old-fashioned. Innerst uses a gentle washes and blocks of color in a warm, muted palette to show us young Ruth’s life as a Jewish girl in Brooklyn; my favorite spread depicts her happily reading in the second floor window of a public library, surrounded by tenements, water towers, fire escapes, tin advertising signs for soda pop, iron gratings, and lurid pink and red Chinese restaurant signs. It’s both specific and impressionistic. The narrative presents Ruth’s life story like a legal case against sexism. “And now, boys and girls of the jury, we offer into evidence some of the more outrageous nonsense Ruth endured,” it proclaims. Exhibit A is Ruth getting her wages slashed at her first job because her boss noticed she was pregnant. Exhibit B is Harvard Law School not providing housing for female students. Exhibit C is Ruth not being allowed to enter the periodical room at the library—where a book necessary for a class is kept—because she’s a woman. Truthfully, I preferred the tighter, simpler text and more creative framing device of last year’s RBG picture book, I Dissent. But ohhhhhhh, this art is unbeatable. (Ages 6-10)

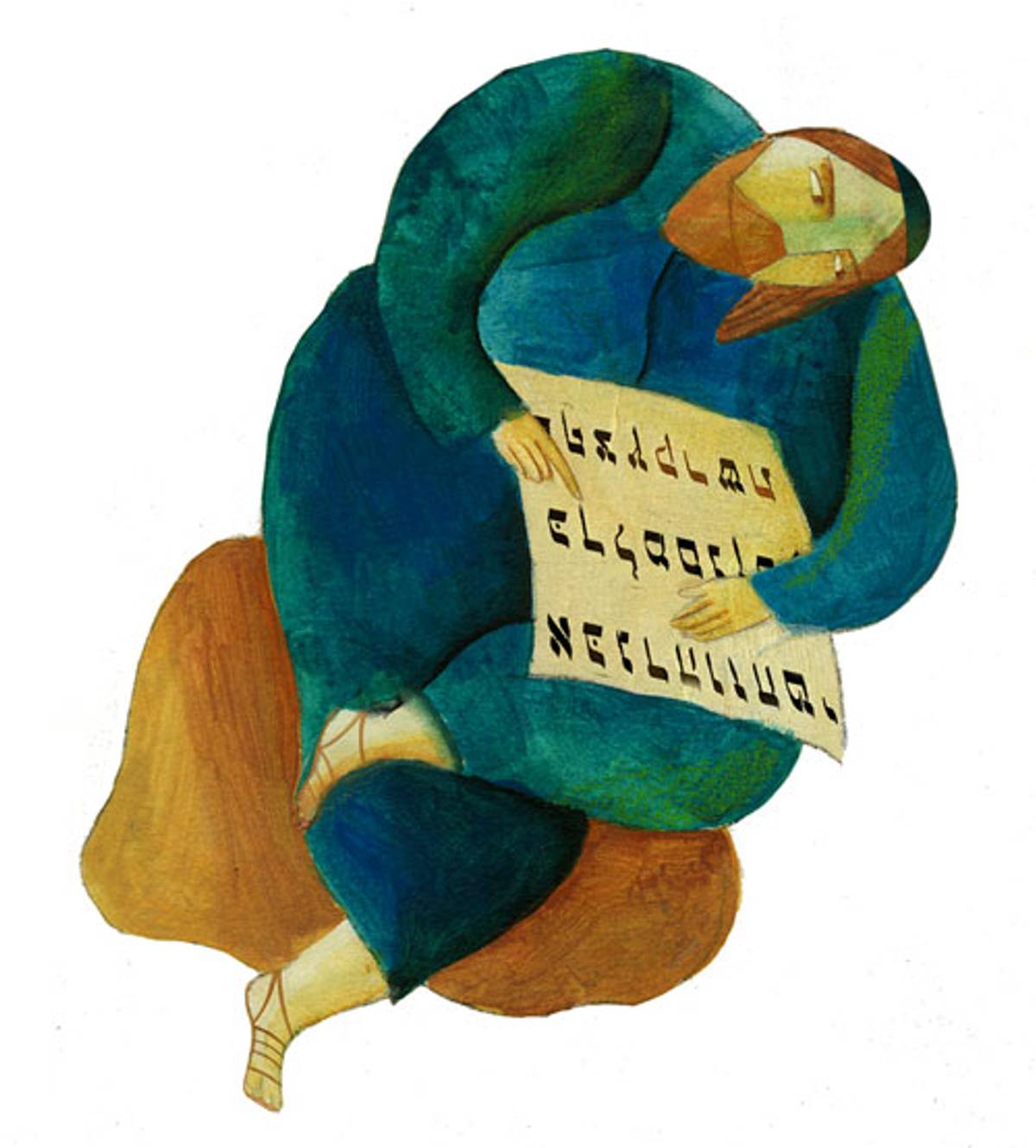

Drop by Drop: A Story of Rabbi Akiva by Jacqueline Jules, illustrated by Yevgenia Nayberg. Second-century sage Rabbi Akiva doesn’t get nearly enough ink. According to tradition, he was born a humble shepherd and didn’t learn to read until he was 40, yet he became one of the greatest rabbis in history. His wife, Rachel, was supposedly the driving force behind his journey from illiterate am-haaretz to brilliant scholar. In this poetic retelling, Rachel encourages Akiva to learn to read and to study Torah. Despite her love and support, he doesn’t believe he’s capable until one day he looks into a brook and sees a rock that has been worn away by steadily dripping water. “Water is soft,” he thinks. “And yet, drop by drop, it has managed to cut through this hard stone. My mind is not harder than a rock!” Eventually, Akiva is hailed by the entire town, but he makes sure everyone knows that Rachel is a hero, too. Nayberg’s sophisticated, intensely colored, theatrical illustrations enhance the lovely writing. A costume and set designer, she brings the drama and intensity of stained-glass windows to her work. The luminous layers of color, swirls of water, striated hills in multiple greens, swoops of fabric in the characters’ robes….just lovely. (Ages 3-7)

Little Red Ruthie: A Hanukkah Tale by Gloria Koster, illustrated by Sue Eastland. Ruthie, in her bright red puffer, sets off for Bubbe’s to make latkes. When a pesky wolf pops up, Ruthie tells him she’ll be much tastier after eight days of carb-loading. At first the wolf agrees to come back later, but then he fails the marshmallow test and races to Bubbe’s. Ruthie hasn’t arrived yet, and Bubbe’s off buying sufganiyot, so the wolf raids Bubbe’s closet. He looks very fetching in a Golden-Girls-esque caftan and high-heeled red booties. When Ruthie gets there, she stalls by relating the tale of the Maccabees (“nobody had ever shared a story with the wolf”) and offers him a latke aperitif before he eats her. Ruthie succeeds in making latkes without Bubbe’s help, and the wolf eats so much he’s too full for the main course. Bubbe gets back—in cool polka-dot tights and nifty faux-fur-topped boots—and sends the wolf on his way with a jelly doughnut. Like the story, the art is bright, friendly and cheerful. I look forward to someone boycotting this book because Ruthie’s mother sends her into the woods alone and Ruthie uses a stove without supervision. (Ages 3-6)

The Art Lesson: A Shavuot Story by Allison and Wayne Marks, illustrated by Annie Wilkinson. Shoshana’s grandma is an artist, with bright red cat-eye glasses and a cat named Krasner. Every Thursday after school, Shoshana goes to her studio—“like an enchanted forest”—to do art. Grandma J calls her “my little Chagall,” “my little Modigliani,” and “my little Pissarro”; Wilkinson’s simple, sweet illustrations contain nods to each of the artists mentioned. For Shavuot, Grandma J and Shoshana make papercuts. Grandma J creates beautiful roses and Torahs, but all Shoshana sees when she unfolds her paper are ugly holes. Grandma J teaches her to see visions in her abstractions: fields of flowers, schools of fish, honeycombs of bees. And many years later, when Shoshana is an artist herself, she teaches her own granddaughter the lessons of Grandma J. A short afterword explains Shavuot, mentions that Eastern European Jews used to make papercuts to hang in their windows for the holiday—who knew? —and gives instructions for a simple Star of David papercut. It also explains who the Jewish artists named in the text are…including Lee Krasner, who was not, in actual fact, a cat. (Ages 3-6)

Big Sam: A Rosh Hashanah Tall Tale by Eric A. Kimmel, illustrated by Jim Starr. Why, it’s a newfangled Jewish-American folktale in the style of an old-school American-American tall tale! Big Sam is a literally larger-than-life figure, making a round challah for Rosh Hashanah by digging a giant hole in the ground for a mixing bowl (“It’s still there today. We call it the Grand Canyon.”), plopping his dough on a geyser by the Yellowstone River so the heat will help it rise, uprooting a fir tree to use as a whisk for an egg-yolk bath, yanking off the top of Mount St. Helens to put the challah in to bake. Lush, old-timey illustrations with a sense of humor depict Sam’s coast-to-coast creative process. When the eagles tell Big Sam, how destructive he’s been, he feels bad. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I forgot that Rosh Hashanah is about mending the world. Whatever I did wrong, I’ll make right.” And he does, planting and digging and fixing. Then Big Sam’s pals Paul Bunyon, Pecos Bill, Slue Foot Sue, John Henry, and Annie Christmas come to celebrate Rosh Hashanah with him. An afterword explains both Rosh Hashanah and tikkun olam, and notes that there are Jewish stories about giants (like Og in the Noah’s Ark story, Samson, and Goliath) as well as American folkloric giants. This is no Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins (the best Hanukkah book ever, by the same author), but it’s mighty fine. (Ages 4-8)

The Cholent Brigade by Michael Herman, illustrated by Sharon Harmer. Young readers will giggle at the main character’s name: Mr. Monty Nudelman. Monty is the guy who shovels everyone’s walk after a snowfall, but after one storm he hurts his back. When he misses shul, everyone says a mi sheberakh, and multiethnic Jewish families from all around the neighborhood send their kids to bring him cholent and good wishes. Everyone chows down, and on Sunday, the kids come back and shovel Monty’s sidewalk. There’s a recipe for cholent (made with BBQ sauce! What madness is this?) at the end. Riotous curly hair, soft clouds of snow, and textured-looking sweaters add to the low-stress fun. (Ages 4-7)

The Knish War on Rivington Street by Joanne Oppenheim, illustrated by Jon Davis. I debated including this one, because I suspect grownups will like it more than most kids. But I was charmed, and it’s my gift guide, dammit. The plot: Two rival knisheries at the turn of the century—one making round knishes, the other making square knishes—battle for hearts and minds and knish supremacy. Luckily, the Lower East Side is big enough and hungry enough to sustain both businesses. An afterword offers two knish recipes—one baked, one fried—and notes that there really was a price war between two Rivington Street knish vendors; the New York Times reported on it in 1916. Oppenheim’s version is entirely fabricated, which raises my hackles a bit; I’m wary of confusing young readers with a mix of true and not-true. That said, the cartoony, detailed illustrations of crowded tenement streets are a delight: Davis clearly did a ton of research into era’s clothing, hairstyles, pushcarts, awnings, and accessories (though he left out the horse poop and tuberculosis), and I can see the Where’s Waldo crowd poring over the pictures. (Ages 4-8)

MIDDLE GRADE

Earlier this year, I wrote about Eyes of the World: Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and the Invention of Modern Photojournalism by Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos, and Refugee by Alan Gratz. Any kid interested in photography will love the former, and any kid with a pulse will love the latter. Here are other great options.

Lucky Broken Girl by Ruth Behar. This beautifully written autobiographical novel tells the story of Ruthie Mizrahi, a 10-year-old Cuban-Jewish girl who has immigrated to New York City in the early 1960s. Ruthie is just beginning to feel at home. She’s learned enough English to be promoted out of the “dumb class,” she’s made two friends, she’s been crowned the Hopscotch Queen of Queens, and her Papi has just given her a coveted pair of white go-go boots like Nancy Sinatra’s—when a terrible accident lands her in bed for an entire year. Trapped in her bedroom, her world shrinks to its most elemental. The descriptions of being in a body cast are harrowing and awful … and full of pee and poop. But Ruthie keeps being surprised by moments of beauty and kindness. Her fabulous new neighbor Chicho paints flowers all over her cast, teaches her about Frida Kahlo, and fills her life with art and balloons and confetti and piñatas. A visiting hippie teacher keeps her in books. Her friend Ramu writes to her from India in his fancy, formal English. Over time, she opens her heart to new people, forgives the boys responsible for the accident, and comes to understand her loved ones’ failings and frailties. Behar, a professor of cultural anthropology, MacArthur “Genius” Award-winner and Guggenheim grant recipient, often writes poetically (“the night is black and blue and purple like an ugly bruise”) but dials it back to pure, powerful minimalism when Ruthie describes horrible things like the accident or her mother’s frustrated cruelty. Ultimately, the story is hugely uplifting, and I loved the variety of people in Ruthie’s world, from a grandparent who fled Poland for Cuba in 1925 and speaks a mix of Spanish and Yiddish (“¿Quieren caramelos, kinderle?”) to a Moroccan-Belgian-Jewish Arabic-and-French-speaking neighbor who feeds her delicious cream puffs, to a tough but loving Puerto Rican nurse from the Bronx. “Why is it that bad things have to happen so you learn that there are lots of good people in the world?” she asks. (Ages 9-12)

This Is Just a Test by Madelyn Rosenberg and Wendy Wan-Long Shang. This is the funniest middle-grade novel I read this year. It’s 1983, and David Da-Wei Horowitz has to contend with his upcoming bar mitzvah, his Chinese and Jewish grandmothers passive-aggressively sniping at each other, a new popular friend urging him to drop a nerdy old friend, a crush on a schoolmate, and absolute terror of nuclear annihilation because he watched The Day After on TV. I am a child of the 1980s, so David’s world of Atari, Battlestar Galactica, learning one’s haftorah by cassette tape, popular girls wearing two polo shirts with both collars popped, Members Only jackets, and freaking out about mushroom clouds was a blast from the past, as it were. I loved David and his super-geek pal Hector, and I wanted Savta and Wei-Po to have their own sitcom. Everything about this book is satisfying, including its conclusion: “I wasn’t half of each; I was all of both.” (Ages 9-13)

The Magician and the Spirits: Harry Houdini and the Curious Pastime of Communicating with the Dead by Deborah Noyes. A strange, beautifully designed (little skulls as borders!), and sneakily affecting look at Houdini’s determination to debunk fake séances and manipulative mediums. Houdini, it seems, was a bit obsessed with death. His dangerous stunts meant that he had regular brushes with it; his father and older brother had both died when he was young; and he was devastated when his beloved mother (“I am what would be called a Mothers-boy,” he once wrote) died while he was performing a continent away. Just as Houdini was becoming a star, Westerners’ belief in “spiritualism” was blossoming. Millions of people had been killed in WWI; millions more died in the 1918 flu epidemic. Everyone, it seemed, had lost someone dear and desperately wanted to talk to them one more time. Houdini’s friend Arthur Conan Doyle was a fervent believer in spirit communication and kept trying to win him over; it destroyed their friendship. (Doyle’s wife led a séance at which she claimed to receive communication from Houdini’s mother, a rabbi’s wife … whose spirit inexplicably covered her letter with crosses.) Noyes discusses some famous charlatans of the day, explains tricks for creating ghostly images and rattling furniture, and quotes Houdini calling mediums “human leeches” and “human vultures.” Discussing one medium’s impressive standard of living, Houdini dryly noted, “His spirit guide seems to have always kept a sharp eye on his need for earthly sustenance.” (Ages 10-15)

YOUNG ADULT

Grendel’s Guide to Love and War by AE Kaplan. A loose modern-day retelling of Beowulf from Grendel’s perspective … if Grendel were a teenager living next door to a douche-y frat-boy-in-training who hosts impossibly loud parties. Tom Grendel’s mom died when he was 9. His dad is an Iraq war vet with PTSD. His sister Zipora is at college. The Rothgar kids next door are equally under-parented, but while Tom fills his days with interviews of old people in the neighborhood and lawn-mowing, the Rothgars throw raging keggers. Tom wants quiet for his fragile father, so he, his Korean-American best friend Ed, and Zipora engage in battle with the monsters next door. The story is very, very funny and sprinkled with casual Jewishness—lots of babka, a little Yiddish, references to wandering in the Sinai, an old bar mitzvah tie used as a dog leash. There’s romance, loss, teamwork, a cute but elusive girl, and reflections on whether we can ever truly know other people. There is also an extended aria of American Girl doll mockery. (Ed, who is hot, clever, and kind, works in the Fifty States Doll store, where he a) sells exceedingly formulaic books in which 10-year-old girls throughout history save their towns through heroic bake sales, and b) flirts with the moms in the café, who tip him handsomely. “It’s like a strip club,” he explains, “Except I don’t have to take my clothes off.”) You needn’t know the story of Beowulf to adore this book. It’s hilarious, menschy, and surprisingly deep. (Age 13 and up.)

Backfield Boys: A Football Mystery in Black and White by John Feinstein. I am not the audience for this book. When a character urges, “circle one of the slots into the seam,” he might as well be speaking Swedish. All I know of America’s Game is that Julian Edelman wrote a children’s book about a Theodor-Herzl-quoting squirrel who plays wide receiver. (That book is not on this list.) But Backfield Boys is a page-turner that’ll entice kids who love the game. After a slow start—urge your kid to read past the first chapter!—the story takes off. Jason Roddin and Tom Jefferson are 14, best friends and Upper West Side public school teammates. Tom is black and a quarterback; Jason is white and Jewish and a receiver. Jason is lightning-fast; Tom is super-smart and super-precise, with a rocket-launcher of an arm. The two get scholarships to a Southern sports academy. When they arrive, though, they discover that Jason’s been put with the quarterbacks and Tom’s with the receivers, and they’re not allowed to room together. It’s immediately clear that the head coach is an asshole. But gradually it becomes evident that something bigger is going on; no black and white kids share rooms, and the academy has never had a black quarterback. The boys and their sympathetic roommates start investigating, and wind up reaching out to two local journalists at rival papers. Together, they uncover just how deep the school’s racism goes. When the evildoers go down, it’s tremendously satisfying. (As a bonus, the book offers an excellent lesson in how investigative journalism works.) Unfortunately, the book’s white kids are more fleshed out than the black ones, and Feinstein’s writing is a bit creaky, studded with references that are unintentionally comic in their ancientness: The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Truman Show, Blue Bloods. (There is not a high school kid on this planet who watches Blue Bloods.) Tom not only knows all about Watergate, he can name the Washington Post city editor in 1972. (“Barry Sussman,” he interjects.) Right. (Ages 12 and up)

The Girl With the Red Balloon by Katherine Locke. Ellie Baum, 16, has grown up with a family legend of how her grandfather Benno escaped a death camp during WWII—the particulars are lost to time and memory, but the story involved a mysterious red balloon and a girl in a purple dress. So when Ellie is on a class trip to Berlin and sees a red balloon floating by, she impetuously grabs it for a selfie. In a blink, she’s transported back in time—not to the Łódź ghetto in the 1940s, but to East Germany in 1988. She’s quickly befriended and protected by Kai, a Romani teenager who grew up in London, and Mitzi, a bright-blue-haired German girl whose family have rejected her because of her sexuality. Kai and Mitzi are Runners, mitzvah-doers who help people escape the East via red balloons and magic. But not even the Balloon Makers themselves, those who forge the magic with mathematics and blood, can figure out how to get Ellie home. Now, it seems, someone is using the balloons wrongfully, to mess with history. Can the three friends find the evildoer? Is Ellie willing to risk getting stuck in time if it means saving others? The story shares three narrators: Ellie, Kai, and Benno. The plotting can get choppy and confusing, and the ending is abrupt, but the premise is wonderful. Ellie and Benno are sympathetic, brave characters, and Kai and Mitzi are delectable. I’d read a whole series of Red Balloon stories. (Ages 13 and up)

Little and Lion by Brandy Colbert. The story opens with Suzette returning from her first year of boarding school, where she’s been sent while her brother Lionel struggles with bipolar disorder. The duo, who call each other Little and Lion, have been tight since they were 6 and 7, when their parents began dating. Suzette’s mom is African-American; Lionel’s dad is white and Jewish; Suzette and her mom have converted to Judaism. (A flashback scene in which Lion quietly, creatively, and very compassionately helps Suzette with a bat-mitzvah-related ethical dilemma is a high point.) Lion’s still coping with his diagnosis and meds; Suzette’s struggling with how to be supportive of her brother and how to manage her own romantic yearnings. She’s discovered she’s bisexual, and feels attracted to both her longtime friend Emil and a new acquaintance, Rafaela. I loved Suzette’s and Lion’s relationship; I loved that the parents are thoughtful, devoted, and cool; I loved Colbert’s way with describing crushy feelings and first kisses; I loved that the family’s mostly-secular Jewish identity is taken seriously (there’s challah and prosciutto, a reflection of the reality of many American Jews’ lives); I loved the sense of place in the book’s Los Angeles setting; I loved Emil. There’s a nearly infinite amount of what the youth of today call “rep”—representation: of black, Jewish, Korean, disabled, and LGBT identities, as well as a sympathetic portrayal of mental illness. What’s not so good: Most of the peripheral characters are so lacking in dimension they might as well be cut-outs. Rafaela is woefully underwritten, and given her importance to the plot, her wispiness does a lot of damage. But for readers who enjoy swoony romance, this is the swooniest book on the list. (Ages 14 and up)

Go forth and read!

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.