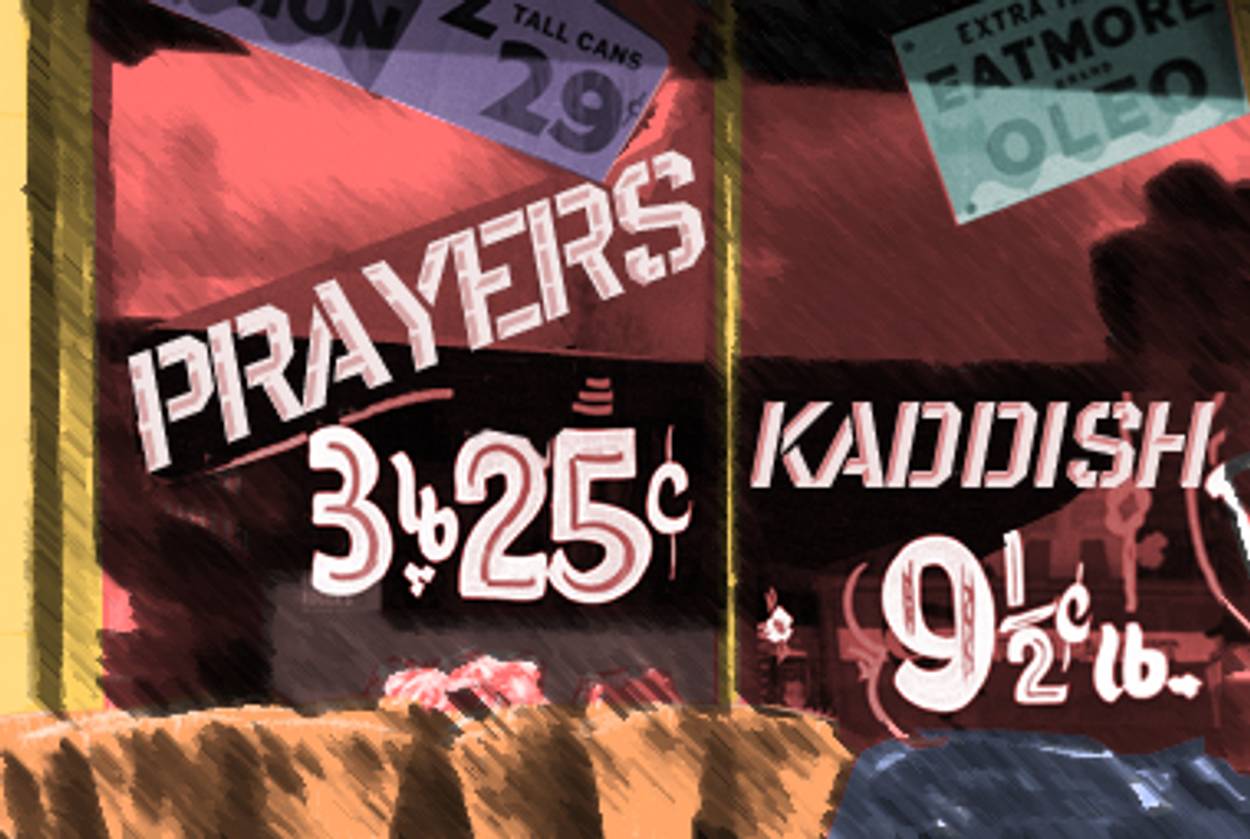

Pay to Pray

From chanting at the Western Wall to saying Kaddish, several organizations offer to pray on your behalf, for a fee they claim to donate to charity. Is a farmed-out prayer as effective as a personal one?

Last week, Jdeal, a Jewish deal-of-the-day website modeled on Groupon, sent out an unusual discounted offer to its 25,000 subscribers. Pay $38 and “a Torah scholar will pray on your behalf at the Kotel for 40 consecutive days ($95 value),” it said. “You too can join the countless individuals who found their beshert, and improved their jobs and health after these prayers.”

It was an astonishing offer. Why farm out a personal prayer? Is a Torah scholar really more effective than the person who’s looking for help from God?

Jerusalem-based Western Wall Prayers offered the deal. The organization was founded in 2004 by Batya and Gershon Burd, a couple who met shortly after Gershon prayed at the Western Wall for 40 consecutive days to find a life partner. The tradition of praying for 40 consecutive days is a long-standing one; in the Bible, Moses prayed on Mt. Sinai for 40 days to ask forgiveness for the sin of the Golden Calf. Western Wall Prayers has offered 7,000 prayers for more than 4,000 people since its inception, Batya Burd wrote in an email. As for money the organization collects, the Jdeal email had said that funds go to “charity to support Jerusalem families.” When asked how much money goes to the Torah scholars and how much to “Jerusalem families,” Burd estimated that 85 percent of the proceeds goes “directly to families of Torah-learners and rabbis and teachers,” and 15 percent to overhead.

One can imagine the appeal of the arrangement for some; it capitalizes on feelings of inadequacy that many have when it comes time to prayer and Jewish knowledge. The Western Wall Prayers site includes profiles of those that it employs as “prayer agents,” and many are affiliated with places like Yeshivas Bircas HaTorah, an Orthodox yeshiva, and Yeshivat Aderet Eliyahu, an ultra-Orthodox yeshiva. The site also employs female prayer agents, according to Batya Burd, but their pictures and biographies aren’t available online. “They are wives of Rebbeum”—meaning rabbis—“and teachers and Torah scholars,” she wrote in an email. The implicit message seems to be that having these holier-than-you men and women pray at Judaism’s most sacred spot will be more effective than if you prayed yourself.

The idea of a prayer proxy is not limited to the Western Wall. A group called Shemirah Bidrachim, Protection on the Road, offers a so-called insurance policy for safe travel. “For a minimal donation, close to two thousand children in our schools will recite Tehilim (Psalms) and additional special tefilos (prayers) of protection for you daily,” the website states. The money raised goes to Ashdod Mercaz Chinuch, a “very frum Orthodox, Israeli yeshiva,” according to the woman who answered the telephone of the number listed on the site. “A couple of hundred people ” have “bought” policies since the program started in 2007, she said.

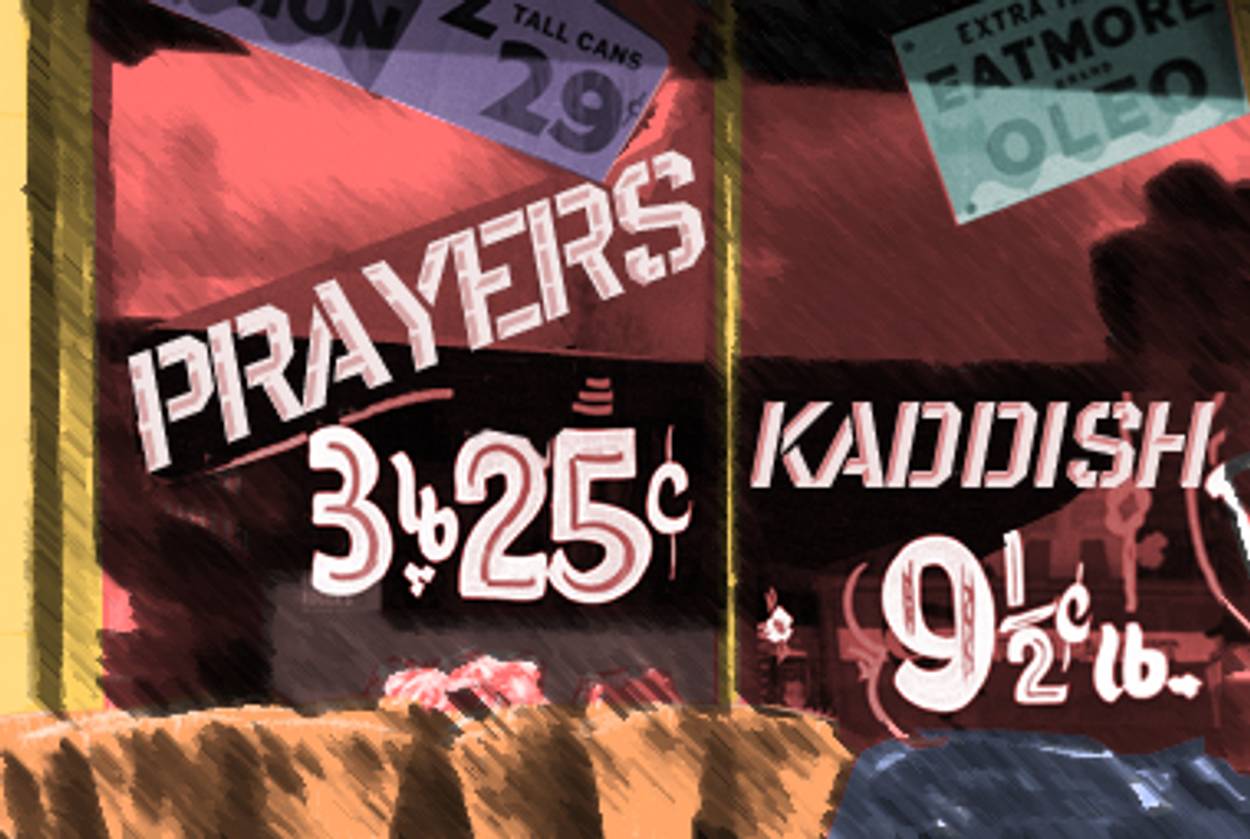

SayKaddish.com is a service run by and benefiting the Lubavitch Youth Organization. For $300, rabbis in Israel will recite Kaddish and Mishna for a deceased loved one on your behalf three times daily for the first year, and then on the annual yahrtzeit. According to the director of the program, Rabbi Shlomo Friedman, the service has been in operation since 1991 and has been used by “thousands” of people. But is it in accordance with Jewish law? An article on Chabad.org says no. “The primary obligation to say Kaddish falls upon the son of the deceased. It is he who is required to recite it. … He and not someone paid to substitute for him.” I asked Rabbi Friedman about this discrepancy. “It’s best when a family member says it,” he said but emphasized that paying someone else to do it is “definitely OK.”

It was once common for Jews to outsource their praying. In the 7th through the 11th centuries, the time of the Geonim, literacy was rare and prayer books rarer. Jewish law acknowledged a hierarchy of know-how in the Jewish community, and it required that prayer leaders have extensive knowledge of Bible and liturgy. It was understood that many people would not be able to read the standardized prayers themselves. But when siddurim became commonly available in the 17th and 18th centuries, and literacy became the norm, rabbinic conventions shifted the onus for prayer back on the individual. “Nowadays, when all are literate, the leader is only for liturgical poems,” the Polish rabbi Avraham Abele ben Hayyim ha-Levi Gombiner, known as the Magen Avraham, wrote in the 17th century.

In his 1981 book When Bad Things Happen to Good People, Rabbi Harold Kushner writes of a stranger calling him very late at night to ask that a prayer be said for his mother, who was having surgery the next morning. “Do I—and does the man who called me—really believe in a God who has the power to cure malignancies and influence the outcome of surgery, and will do that only if the right person recites the right words in the right language?” Kushner writes. “And will God let a person die because a stranger, praying on her behalf, got some of the words wrong?” Is my own prayer for good health less compelling to God than if the same prayer is offered by a Torah scholar at the Western Wall?

In the Berachot tractate of the Talmud, the rabbis explicate the laws of the Amidah, the central prayer in Jewish liturgy, by returning to Hannah’s prayer. Hannah was a barren woman whose personal prayer for a son was answered by God, even though she looked so strange while praying that she was assumed to be drunk. Hannah’s prayer was used by the rabbis to set the standards for the most important piece of liturgy in Judaism, but somewhere along the way the personal nature of her words has fallen by the wayside. It’s the personal conviction, or kavannah, that we give our prayers that makes them so worthwhile and indelibly ours.

Prayer, after all, is not just about results. The Hebrew word lehitpallel, to pray, is a reflexive verb, that could more accurately be translated as “to judge oneself.” If you look to prayer as merely a way to get what you want, you’ll be disappointed. If you look at it as a spiritual practice, a way to evaluate yourself and your needs, and to address God as best you can, you’re more likely to derive benefit. But, still, there are no guarantees, even if you pay $38.

Tamar Fox is an associate editor at MyJewishLearning.com.

Tamar Fox is an associate editor at MyJewishLearning.com.